Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2005 Next Wave Festival

November 2005 2005 Next Wave Festival Mary Heilmann, Last Chance for Gas Study (detail), 2005 BAM 2005 Next Wave Festival is sponsored by: The PerformingNCOREArts Magazine Altria 2005 ~ext Wave FeslliLaL Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman William I. Campbell Chairman of the Board Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins Joseph V. Melillo President Executive Prod ucer presents Symphony No.6 (Plutonian Ode) & Symphony No.8 by Philip Glass Bruckner Orchestra Linz Approximate BAM Howard Gilman Opera House running time: Nov 2,4 & 5, 2005 at 7:30pm 1 hour, 40 minutes, one intermission Conducted by Dennis Russell Davies Soprano Lauren Flanigan Symphony No.8 - World Premiere I II III -intermission- Symphony No. 6 (Plutonian Ode) I II III BAM 2005 Next Wave Festival is sponsored by Altria Group, Inc. Major support for Symphonies 6 & 8 is provided by The Robert W Wilson Foundation, with additional support from the Austrian Cultural Forum New York. Support for BAM Music is provided by The Aaron Copland Fund for Music, Inc. Yamaha is the official piano for BAM. Dennis Russell Davies, Thomas Koslowski Horns Executive Director conductor Gerda Fritzsche Robert Schnepps Dr. Thomas Konigstorfer Aniko Biro Peter KeserU First Violins Severi n Endelweber Thomas Fischer Artistic Director Dr. Heribert Schroder Heinz Haunold, Karlheinz Ertl Concertmaster Cellos Walter Pauzenberger General Secretary Mario Seriakov, Elisabeth Bauer Christian Pottinger Mag. Catharina JUrs Concertmaster Bernhard Walchshofer Erha rd Zehetner Piotr Glad ki Stefa n Tittgen Florian Madleitner Secretary Claudia Federspieler Mitsuaki Vorraber Leopold Ramerstorfer Elisabeth Winkler Vlasta Rappl Susanne Lissy Miklos Nagy Bernadett Valik Trumpets Stage Crew Peter Beer Malva Hatibi Ernst Leitner Herbert Hoglinger Jana Mooshammer Magdalena Eichmeyer Hannes Peer Andrew Wiering Reinhard Pirstinger Thomas Wall Regina Angerer- COLUMBIA ARTISTS Yuko Kana-Buchmann Philipp Preimesberger BrUndlinger MANAGEMENT LLC Gorda na Pi rsti nger Tour Direction: Gudrun Geyer Double Basses Trombones R. -

Bruckner Orchester Linz

Bruckner Orchester Linz Dennis Russell Davies Conductor Martin Achrainer / Bass-Baritone Angélique Kidjo / Vocals Thursday Evening, February 2, 2017 at 7:30 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor 35th Performance of the 138th Annual Season 138th Annual Choral Union Series Tonight’s presenting sponsor is Michigan Medicine. Tonight’s supporting sponsor is the H. Gardner and Bonnie Ackley Endowment Fund. Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM, WRCJ 90.9 FM, Ann Arbor’s 107one, and WDET 101.9 FM. Special thanks to Tom Thompson of Tom Thompson Flowers, Ann Arbor, for his generous contribution of lobby floral art for this evening’s performance. The Bruckner Orchester Linz is the Philharmonic Orchestra of the State of Upper Austria, represented by Governor Dr. Josef Puehringer. The Bruckner Orchester Linz is supported by presto – friends of Bruckner Orchester. Bruckner Orchester Linz appears by arrangement with Columbia Artists Management, Inc. Angélique Kidjo appears by arrangement with Red Light Management. In consideration of the artists and the audience, please refrain from the use of electronic devices during the performance. The photography, sound recording, or videotaping of this performance is prohibited. PROGRAM George Gershwin, Arr. Morton Gould Porgy and Bess Suite Alexander Zemlinsky Symphonische Gesänge, Op. 20 Song from Dixieland Song of the Cotton Packer A Brown Girl Dead Bad Man Disillusion African Dance Arabesque Mr. Achrainer Intermission Duke Ellington, Arr. Maurice Peress Suite from Black, Brown, and Beige Black Brown Beige Philip Glass Ifè: Three Yorùbá Songs Olodumare Yemandja Oshumare Ms. Kidjo 3 PORGY AND BESS SUITE (1935, ARRANGED IN 1955) George Gershwin Born September 26, 1898 in Brooklyn, New York Died July 11, 1937 in Hollywood, California Arr. -

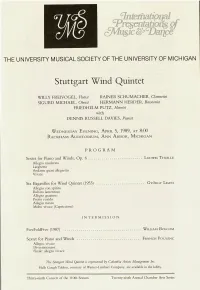

^T&Mtioqal Stuttgart Wind Quintet

^t&Mtioqal THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Stuttgart Wind Quintet WILLY FREIVOGEL, Flutist RAINER SCHUMACHER, Clarinetist SIGURD MICHAEL, Oboist HERMANN HERDER, Bassoonist FRIEDHELM PUTZ, Homist with DENNIS RUSSELL DAVIES, Pianist WEDNESDAY EVENING, APRIL 5, 1989, AT 8:00 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Sextet for Piano and Winds, Op. 6 ............................ LUDWIG THUILLE Allegro moderate Larghetto Andante quasi allegretto Vivace Six Bagatelles for Wind Quintet (1953) ......................... GYORGY LIGETI Allegro con spirito Rubato lamentoso Allegro grazioso Presto ruvido Adagio mesto Molto vivace (Capriccioso) INTERMISSION FiveFoldFive (1987) ........................................ WILLIAM BOLCOM Sextet for Piano and Winds ................................. FRANCIS POULENC Allegro vivace Divertissement Finale: allegro vivace The Stuttgart Wind Quintet is represented by Columbia Artists Management Inc. Halls Cough Tablets, courtesy of Warner-Lambert Company, are available in the lobby. Thirty-ninth Concert of the 110th Season Twenty-sixth Annual Chamber Arts Series PROGRAM NOTES Sextet for Piano and Winds, Op. 6 ........................ LUDWIG THUILLE (1861-1907) Ludwig Thuille's greatest distinction as a composer is his devotion to the cultivation of chamber music at a time when most composers were ignoring the medium. Although he composed several operas on whimsical subjects (Lobetanz, composed in 1896, was heard regularly in New York at the turn of the century), his instrumental and vocal chamber music remain part of the standard repertoire. As an educator, his music theory textbook Harmonielehre, written in 1907 with Rudolf Louis, remained the authoritative work on the subject long after Thuille's death. The Sextet for Piano and Winds, Op. 6, was written in 1889 and was an immediate success. -

Season 2020|2021 2021 | Season 2020

65th Concert Season Season 2020|2021 2021 | Season 2020 . A word from the Filharmonie Brno Managing Director Dear music lovers invite you to a social gathering over a glass Paľa. Leoš Svárovský is preparing for C. M. you! I am very happy that we enter the new of wine, from 6pm before the concerts at von Weber’s celebrated Bassoon Concerto season with the support of our exceptional You are holding in your hands our brand Besední dům (Filharmonie at Home series), with the virtuoso Guilhaume Santana and volunteers for the second time now, who new catalogue for the 2020/2021 sea- where you can learn plenty of interesting Roussel’s Le festin de l’araignée – with this help us with concerts and education – son: this time, it is not just the content that is facts about the programme and meet the concert, the former chief conductor of our thank you, everyone! new – the format is, too. We’ve aimed to evening’s artists in person. orchestra will celebrate an important anni- I am writing these words at a time when make the navigation easier, and to high- The new season is the work of the Filhar- versary in his life. Gerrit Prießnitz will focus we are all paralysed by the coronavirus light the unique characteristics of our sub- monie Brno chief conductor and artistic on the emotional topic of Hamlet in the pandemic and are not yet sure what the ul- scription concerts – each of them offers a director Dennis Russell Davies and the pro- works of Tchaikovsky and Walton. -

•••I Lil , .1, Llle! E

1114 IEIT liVE FESTIVIL 1994 NEXT WAVE COVEll AND POSTER AR11ST ROBERT MOS1tOwrrz •••I_lil , .1, lllE! II I E 1.lnII ImlEI 14. IS BAMBILL BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President & Executive Producer THE BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA Dennis Russell Davies, Principal Conductor Lukas Foss, Conductor Laureate 41st Season, 1994/95 MIRROR IMAGES in the BAM Opera House October 14, 15, 1994 PRE-CONCERT RECITAL at 7pm PHILIP GLASS Six Etudes Dennis Russell Davies, Piano (American premiere) BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA DENNIS RUSSELL DAVIES, Conductor MARGARET LENG TAN, Piano 8pm JOHN ZORN For Your Eyes Only (BPO Commission) CHEN YI Piano Concerto Margaret Leng Tan, Piano (BPO commission; premiere performance) - Intermission - PHILIP GLASS Symphony No.2 (BPO commission; premiere performance) Allegro Andante Allegro POST-CONCERT DIALOGUE with Chen Yi, Philip Glass, Dennis Russell Davies, and Joseph Horowitz Philip Glass' Symphony No.2 is commissioned by BPO with partial funding provided by the Mary Flagler Cary Charitable Trust. Symphony No.2 composed by Philip Glass. Copyright 1994 Dunvagen Music Publishers, Inc. THE STANLEY H. KAPLAN EDUCATIONAL CENTER ACOUSTICAL SHELL The Brooklyn Philharmonic and the Brooklyn Academy of Music gratefully acknowledge the generosity of Mr. and Mrs. Stanley H. Kaplan, whose assistance made possible the Stanley H. Kaplan Educational Center Acoustic Shell. THE BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA IS THE RESIDENT ORCHESTRA OF BAM. _ MIRROR IMAGES _ mainly associate£! with opera; ballet. film. and experimentaltheatet~ the opportuni f,r to "think a\Jour tne tradition of &Ythphonic musk;/' Glass haSstateu. openeu "a new world ofmusic--and I am very much looking forward to what I will discover." Glass's Symphony No. -

Philip Glass' Days and Nights Festival Launches Streaming Portal Featuring Films of Landmark Performances

PHILIP GLASS’ DAYS AND NIGHTS FESTIVAL LAUNCHES STREAMING PORTAL FEATURING FILMS OF LANDMARK PERFORMANCES VISIONARY MODEL AIMS TO PROVIDE INCOME TO ARTISTS 10TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION OF FESTIVAL TO BE VIRTUAL IN 2021 Jerry Quickley performing Whistleblower at the 2014 Days and Nights Festival; Photo credit: Arturo Béjar February 4, 2021—The annual multidisciplinary Days and Nights Festival—which since 2011 has taken place in and around Big Sur, California and has brought together luminaries and pioneers in fields including music, dance, theater, literature, film and the sciences—launches today its premiere streaming portal featuring exclusive films of a selection of its landmark performances and events. Click HERE or visit PhilipGlassCenterPresents.org, and see below for upcoming film details and release dates. Conceived and developed by world-renowned American composer Philip Glass—who has taken part every year since inception—Days and Nights is designed to encompass arts of all disciplines and nurture them in a way that welcomes the future while exploring seminal developments throughout history. Key to that vision are collaborations between artists from across a broad range of disciplines, and the selection of films slated for release includes contributions by such wide-ranging figures as JoAnne Akalaitis, Tibetan artist Tenzin Choegyal, Danny Elfman, Molissa Fenley, María Irene Fornés, Allen Ginsberg, Dev Hynes (Blood Orange), Jerry Quickley and Glass himself. Featured performers and ensembles include Dennis Russell Davies, Ira Glass, Matt Haimovitz, Tara Hugo, Lavinia Meijer, Maki Namekawa, Gregory Purnhagen, Third Coast Percussion, Opera Parallèle and Glass and his Philip Glass Ensemble. See below for details. “From the beginning, I wanted it to be a cross-cultural festival, but not just in terms of musicians from different parts of the world. -

News Release

news release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS CONTACTS: Maggie Stapleton (ACO/EarShot) February 12, 2019 646.536.7864 x2; [email protected] Siobhan Rodriguez (Sarasota Orchestra) 941.487.2746; [email protected] EarShot and Sarasota Orchestra Present Brand New Orchestral Works by Four Emerging Composers Krists Auznieks, Nicky Sohn, Sam Wu, Kitty Xiao Saturday, March 16, 2019 at 8pm Holley Hall | 709 N Tamiami Trail | Sarasota, FL Tickets: $15 - $30 and more information available at www.sarasotaorchestra.org EarShot: bit.ly/earshotnetwork Sarasota, FL – On Saturday, March 16, 2019 at 8pm, EarShot (the National Orchestral Composition Discovery Network) and the Sarasota Orchestra present the readings of new works by four emerging composers at Holley Hall (709 N Tamiami Trail). Led by Los Angeles based conductor Christopher Rountree, the New Music Readings will be the culmination of a series of private readings, feedback sessions, and work with mentor composers Robert Beaser, Laura Karpman, and Chinary Ung. The selected composers and their works, chosen from a national call for scores that yielded 127 applicants, are Krists Auznieks (Crossing), Nicky Sohn (Bird Up), Sam Wu (Wind Map), and Kitty Xiao (Ink and Wash). Additional activities include professional development panels with the mentor composers and guests William J. Lackey of American Composers Forum, Stephen Miles of New College of Florida, and select staff from the Sarasota Orchestra administrative team. “Sarasota Orchestra is thrilled to be a partner for the ACO’s Earshot initiative and a leader on the national forefront of orchestras raising the profile of emerging composers,” said Sarasota Orchestra President/CEO Joseph McKenna. -

Schooltime and Family Concerts

I am most eager to begin my work with the Brooklyn Philharmonic. For an itinerant conductor such a commitment is ideal ; all the more so with an orchestra of such distinguished history and artistic commitment as the BPO. It is an honor to fol low in the footsteps of Lukas Foss and Dennis Russell Davies. I look MYyears with the Brooklyn forward to calling Brooklyn home. Philharmonic have been exciting and fulfilling ones for me, and I approach this season with a cer Robert Spano tain sadness knowing that I will miss musicians and staff very much. It is therefore especially gratifying that the orchestra was able to attract a fine , innovative and dedicated conductor like Robert Spano to continue our pro gram. The BPO's future is in excellent hands. Dennis Russell Davies Robert C. Rosenberg Chairman of the Board Artistic II the audience of the future The 1994-95 Season When Peter G. Davis, in New York Magazine, The weekend in question, "Paradise Lost," named the "best" and "worst" musical events also included music by Hindemith and of 1995, the Brooklyn Philharmonic was the Mahler- programming variously described in only organization to make both lists. This the press as "peculiar, " "outrageous," "gen seemed the ultimate accolade. uinely interesting," and "ingenious. " Beyond a doubt, many at BAM that weekend were As surely as the Brooklyn Academy of Music, exposed to Hindemith and Mahler for the for which it is Orchestra in Residence, BPO first time. Their reactions were vividly shuns business as usual. demonstrative. Swed, in The Wall Street The highlights of the 1994- 95 season Journal, reported seeing a young woman included a weekend with Marianne Faithful! "theatrically gasping for air at intermission" singing Kurt Weill. -

Fain Has the Honeyed Tone, Spectacular Technique and Engrossing Musicality of an Old-School Virtuoso Tied to a Contemporary Sensibility.” – LOS ANGELES TIMES

“Fain has the honeyed tone, spectacular technique and engrossing musicality of an old-school virtuoso tied to a contemporary sensibility.” – LOS ANGELES TIMES With his adventuresome spirit and vast musical gifts, violinist Tim Fain has emerged as a mesmerizing presence on the music scene. The “charismatic violinist with a matinee idol profile, strong musical instincts, and first rate chops” (Boston Globe), was seen on screen and heard on the Grammy nominated soundtrack to the film Black Swan, can be heard on the soundtrack to Moonlight and gave “voice” to the violin of the lead actor in the hit film 12 Years a Slave, as he did with Richard Gere’s violin in the film Bee Season. Fain captured the Avery Fisher Career Grant and launched his career with Young Concert Artists. He electrified audiences in performances with the Pittsburgh, Chautauqua, and Cabrillo and Baltimore (both with Marin Alsop) Symphonies, at Lincoln Center’s Mostly Mozart Festival, with the Orchestra of St. Luke’s, and most recently with the American Composers Orchestra at Carnegie Hall. Fain has also appeared with the Mexico City, Tucson, Oxford (UK), and Cincinnati Chamber Symphonies, Brooklyn, Buffalo and Hague Philharmonics, National Orchestra of Spain (with conductor Dennis Russell Davies), and the Curtis Symphony Orchestra in a special performance at Philadelphia’s Kimmel Center. In addition, he was the featured soloist with the Philip Glass Ensemble at Carnegie Hall in a concert version of Einstein on the Beach and continues to tour the US and Europe in a duo-recital -

Keith Jarrett Discography

Keith Jarrett Discography Mirko Caserta , [email protected] July 20, 2002 I cannot say what I think is right about music; I only know the “rightness” of it. I know it when I hear it. There is a release, a flowing out, a fullness to it that is not the same as richness or musicality. I can talk about it in this way because I do not feel that I “created” this music as much as I allowed it to “emerge”. It is this emergence that is inexplicable and incapable of being made solid, and I feel (or felt) as though not only do you never step in the same river twice, but you are never the same when stepping in the river. The river has always been there, despite our polluting it. This is a miracle, and in this day and age we need it. At least I do. – Keith Jarrett, from Spirits’ cover Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 How it all started ........................................... 5 1.2 Availability .............................................. 5 1.3 Other resources ............................................ 6 1.4 Acknowledgements .......................................... 6 1.5 Copyleft Notice ............................................ 7 1.6 Disclaimer ............................................... 7 1.7 How to contribute .......................................... 7 1.8 Documentation Conventions ..................................... 7 2 The years ranging from 1960 to 1970 8 2.1 Swinging Big Sound, (Don Jacoby and the College All-Stars) .................. 8 2.2 Buttercorn Lady, (Art Blakey and the New Jazz Messengers) .................. 8 2.3 Dream Weaver, (Charles Lloyd Quartet) .............................. 8 2.4 The Flowering of the Original Charles Lloyd Quartet Recorded in Concert, (Charles Lloyd Quartet) ................................................ 8 2.5 Charles Lloyd in Europe, (Charles Lloyd Quartet) ....................... -

Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-22-1997 Guest Artist Concert: Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra Dennis Russell Davies Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra and Davies, Dennis Russell, "Guest Artist Concert: Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra" (1997). All Concert & Recital Programs. 4828. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/4828 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERTS 1996-97 STUTTGART CHAMBER ORCHESTRA Dennis Russell Davies, chief conductor Aria: "O Mensch bewein dein Stinde gross" Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) transcribed by Max Reger Rondo for Violin and Strings in A Major, D. 438 Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Benjamin Hudson, violin In commemoration of the Schubert Bicentennial Grosse Fuge in B-flat Major, op. 133 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) ,_) Overtura: A//egro--A//egro---Fuga IN1ERMISSION Symphony No. 3 (1994) Philip Glass (b. 1937) (in/our movements) (Commissioned by the Stiftung Wurth Corporation in honor of the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra's 50th Anniversary) Ford Hall Auditorium Tuesday, April 22, 1997 8:15 p.m. Columbia Artists Management Inc. Sheldon/Connealy Division R. Douglas Sheldon The Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra records for ECM, Orfeo, Discover and Mediaphon. Dennis Russell Davies records for Argo, BMG, ECM, Musicmasters, Discover and Point Records. STUTTGART CHAMBER ORCHESTRA Dennis Russell Davies, chief conductor In the Spring of 1997, the internationally celebrated Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra returns for its twelfth North American tour since its acclaimed debut on this continent in 1950. -

Annual Report 2018-19

AANNUALNNUAL REPORTREPORT 22018-19019-20 Photo credits: Pete Checchia, Jiayi Liang, Jennifer Taylor LETTERS FROM THE LEADERSHIP We look back at the 2018-19 season and marvel at the com- tained our regular rotation of concerts, readings and education pro- munity of artists and audience that converged at ACO events. grams, while renewing and deepening our commitment to diversity, George, Derek and Ed program an ever-adventurous and equity and inclusion. horizon-expanding repertoire. This season’s Carnegie Hall series brought us a sci-fi opera by Alex Temple, a concerto for Imani One thing that remains constant: ACO is committed to furthering the Winds by Valerie Coleman, a multimedia oratorio by Du Yun cause of American composers. Whether we are teaching students in and Khaled Jarrar, a rarely heard work by Morton Feldman, and New York City public schools, partnering with orchestras in Phila- the recognition of two composers celebrating their 80th Birth- delphia, Grand Rapids, Sarasota, and Detroit, or performing with days: Joan Tower and Gloria Coates. ACO’s incomparable Music Director George Manahan, compos- ers of every age, race, gender, and musical background can find We’re also proud of progress made in the first year of our three- their voices with us. We look forward to continuing the work of this year strategic plan. Thanks to generous funders like the Altman year to create an even more vibrant future for American music and Foundation and the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund, we added ingenuity. new staff. From July through October, we welcomed our new Emerging Composers and Diversity Director Aiden Feltkamp and Sincerely, expanded our development staff to include full-time Develop- ment Associate Stephanie Polonio and part-time Grants Writer Frederick Wertheim Sameera Troesch Jay House.