How Tea Shaped the Modern World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EVERYTHING SERVED ALL DAY Your Table Number

Please order at the bar with MENU EVERYTHING SERVED ALL DAY your table number... BREAKFAST & BRUNCH – SERVED ALL DAY Our scrambled egg includes tomato and basil NEW The Boss £10.95 Flatbreads West Country Breakfast £8.50 Bacon, sausage, hog’s pudding, Za’atar flatbread, date chutney, harissa, herb Bacon, sausage, scrambled egg, roasted mushrooms, roasted new potatoes, salad, Greek yoghurt, toasted sesame seeds, tomatoes, baked beans, toast roasted tomatoes, baked beans, pickled red onion, sumac Veggie Breakfast £8.25 scrambled egg, two rounds of toast ...with spiced lamb £9.50 ...with crispy halloumi £9.25 Roasted new potatoes, mushrooms, Chorizo Hash £8.75 baked beans, roasted tomatoes, Poached eggs, mushrooms, spinach, Grain Bowls scrambled egg, toast roasted tomatoes Buckwheat, black quinoa, avocado, lime Vegan option available £6.95 pickled beetroot, orange, harissa, Greek Sweetcorn Hash £8.75 £6.35 yoghurt, nuts & seeds Mushrooms on Halloumi, poached eggs, avocado & tomato Sourdough Toast ...with pork belly salsa, coriander, Tabasco maple syrup £10.95 ...with hot smoked mackerel £10.25 Vegan option available Sourdough Eggy Bread with £8.75 Poached or Scrambled Eggs £5.00 Smoked Bacon & Avocado Cheddar & Jalapeño £8.75 on Toast Veggie option £7.75 Cornbread ...add smoked salmon £2.60 Fried egg, smashed avocado, spicy salsa, ...add smoked bacon £2.50 Smoked Salmon, Avocado £8.75 yoghurt, coriander, Tabasco maple syrup ...add mushrooms £2.10 & Scrambled Eggs Eggs Royale £8.75 On sourdough toast Baps Eggs Benedict £7.95 Sausage or smoked -

MARKETS for INDIAN TEA in the UNITED STATES and CANADA. Our Readers Will Have Noticed That Messrs. Doane & Co. of Chicago Es

MARKETS FOR INDIAN TEA IN THE of the Tycoon to enter into “ the comity of the UNITED STATES AND CANADA. nations.” Our first taste of the amber-coloured, burnt Our readers will have noticed that Messrs. Doane flavoured tea, which is such a favourite with our & Co. of Chicago estimated the consumption of tea in Yankee cousins was in Paris, a good many years the United States at 72,000,000 lb. Mr. Sibthorp’s ago. It was provided for us as a treat by the then calculation is not so high, his figures being a little correspondent of the Daily News, but we could not under 70,000,000 lb. The population of the United honestly say that we admired it. Taste in regard States being fully fifty millions, it follows that the for tea is, however, very much a matter of educa consumption of tea is considerably under 1J lb. per tion : some people do not take kindly to Indian caput. In Britain, the consumption of tea last year tea at once, and a few persons are so depraved in taste exceeded 160,000,000, lb., which, for a population of as not to admire even the Ceylon leaf, until the second thirty-five millions, gives, for each individual, over or third time of tasting. The extreme cold of the 4£ lb. In regard to coffee, the position of the two climate in Canada and parts of the United States, countries is more than reversed ; for the pe?ple of may, perhaps (?) account for the preference given to Britain have been so thoroughly cheated and disgusted highly -fired and green teas, which have almost ceased in the matter of coffee, that they do not now consume to be used in Britain and which, recently tried on anything like a pound a head of this beverage. -

The Demand Curve in the Boston Tea Party: When All Else Fails, Shift the Demand, Ye Patriots

Document Section 2 The Demand Curve in the Boston Tea Party: When all else fails, shift the Demand, ye Patriots. BACKGROUND: Students should have prior knowledge of the economic models describing supply and demand. Students should have working knowledge of shifting and movement along the demand and supply curves. Knowledge of marginal utility analysis is also assumed. Application of the theory of indifference curves in the creation of the demand curve could be helpful but not necessary for this exercise. GOAL: Students will apply their knowledge of supply and demand analysis to the events leading up to the Boston Tea Party. They will evaluate the effectiveness of their models in describing the consumer behavior of tea. CONCEPT REVIEW: Using regular demand/supply analysis, describe 1. What factors cause a shift in demand? 2. What factors cause a movement along the demand curve? DOCUMENT ANALYSIS: Read the following set of documents pertaining to the background of the Boston Tea Party. 1. On a separate piece of paper answer the “Consider” question that corresponds with each document. 2. Discuss your answers with your group and come to some consensus over the meaning of the documents. 3. GRAPH—Using your best demand/supply analysis, show how the Patriots were shaping and influencing the market for tea in the years leading up to the Boston Tea Party. TASK: Based on the documents and your knowledge of 18th century American history, do you think the Patriots were able to change demand for tea? Why or why not? Would you recommend it as sound policy to continue to try to change demand? If so, how would you go about it? If not, what might you do instead to keep up with the demand? Be able to provide a coherent explanation to your fellow Patriots. -

GROUP TEA PARTY RESERVATION SIP Tea Room Policies & Agreement: 6-12 Guests

..r GROUP TEA PARTY RESERVATION SIP Tea Room Policies & Agreement: 6-12 guests Please find a list of all the very boring, yet very important, details below. We are grateful for your consideration and look forward to being a part of your special day. Terms & Conditions • Capacity: In order to accommodate all guests, we limit parties in the tea room to 12 guests. *We offer full private rental of the Tea Room for parties of 13-30, visit our website for full details on Private Tea Room Rentals. • Availability: Large party reservations begin at 11:00am, 1:00pm or 3:00pm. • Time Limits: Parties are reserved for 1 hour 45 minutes. Please note that the party must be completed by the agreed upon time. In order for us to properly clean and seat our next reservation, it is imperative that the space be vacated on time. In the event that guests stay over the allotted time, a fee may be charged. • Children (8 years and under). We have found that a max of 5 children is ideal for the tea room seating. Our facility is best suited for those ages 8 or older. We do not have space for large stroller’s. No highchairs available. • Space Usage: There is NOT room to open gifts, play games or give speeches in the tea room – consider a Private Tea Room Rental if you wish to have activities. • No Last-Minute Guests: Host must make sure that the number of guests does not over-exceed the guaranteed number. We do not “squeeze” in guests. -

Tea Drinking Culture in Russia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hosei University Repository Tea Drinking Culture in Russia 著者 Morinaga Takako 出版者 Institute of Comparative Economic Studies, Hosei University journal or Journal of International Economic Studies publication title volume 32 page range 57-74 year 2018-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10114/13901 Journal of International Economic Studies (2018), No.32, 57‒74 ©2018 The Institute of Comparative Economic Studies, Hosei University Tea Drinking Culture in Russia Takako Morinaga Ritsumeikan University Abstract This paper clarifies the multi-faceted adoption process of tea in Russia from the seventeenth till nineteenth century. Socio-cultural history of tea had not been well-studied field in the Soviet historiography, but in the recent years, some of historians work on this theme because of the diversification of subjects in the Russian historiography. The paper provides an overview of early encounters of tea in Russia in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, comparing with other beverages that were drunk at that time. The paper sheds light on the two supply routes of tea to Russia, one from Mongolia and China, and the other from Europe. Drinking of brick tea did not become a custom in the 18th century, but tea consumption had bloomed since 19th century, rapidly increasing the import of tea. The main part of the paper clarifies how Russian- Chines trade at Khakhta had been interrelated to the consumption of tea in Russia. Finally, the paper shows how the Russian tea culture formation followed a different path from that of the tea culture of Europe. -

A Russian Tea Wedding an Interview with Katya & Denis

Voices from the Hut A Russian Tea Wedding An Interview with Katya & Denis This growing community often blows our hearts wide open. It is the reason we feel so inspired to publish these magazines, build centers and host tea ceremonies: tea family! Connection between hearts is going to heal this world, one bowl at a time... Katya & Denis are tea family to us all, and so let’s share in the occasion and be distant witnesses at their beautiful tea wedding! 茶道 ne of the things we love the imagine this continuing in so many dinner, there was a party for the Bud- O most about Global Tea Hut is beautiful ways! dhists on the tour and Denis invited the growing community, and all the We very much want to foster Katya to share some puerh with him. beautiful family we’ve made through community here, and way beyond It was the first time she’d ever tried tea. As time passes, this aspect of be- just promoting our tea tradition. It such tea, and she loved it from the ing here, sharing tea with all of you, doesn’t matter if you practice tea in first sip. Then, in 2010, Katya moved starts to grow. New branches sprout our tradition or not, we’re family—in from her birthplace in Siberia, every week, and we hear about new our love for tea, Mother Earth and Komsomolsk-na-Amure, to Moscow and amazing ways that members are each other! If any of you have any to live with Denis (her hometown is connecting to each other. -

What Every Dentist Should Know About Tea

Nutrition What every dentist should know about tea Moshe M. Rechthand n Judith A. Porter, DDS, EdD, FICD n Nasir Bashirelahi, PhD Tea is one of the most frequently consumed beverages in the world, of drinking tea, as well as the potential negative aspects of tea second only to water. Repeated media coverage about the positive consumption. health benefits of tea has renewed interest in the beverage, particularly Received: August 23, 2013 among Americans. This article reviews the general and specific benefits Accepted: October 1, 2013 ea has been a staple of Chinese life for their original form.4 Epigallocatechin-3- known as reactive oxygen species (ROS) so long that it is considered to be 1 of galate (EGCG) is the principal bioactive are formed through normal aerobic cellular Tthe 7 necessities of Chinese culture.1 catechin left intact in green tea and the metabolism. During this process, oxygen is The popularity of tea should come as no one responsible for many of its health partially reduced to form a reactive radical surprise considering the recent studies benefits.3 By contrast, black tea is fully as a byproduct in the formation of water. conducted confirming tea’s remarkable oxidized/fermented during processing, ROS are helpful to the body because they health benefits.2,3 The drinking of tea dates which accounts for both its stronger flavor assist in the degradation of microbial back to the third millenium BCE, when and the fact that its catechin content is disease.5 However, ROS also contain free Shen Nong, the famous Chinese emperor lower than the other teas.2 Black tea’s fer- radical electrons that can wreak havoc on and herbalist, discovered the special brew. -

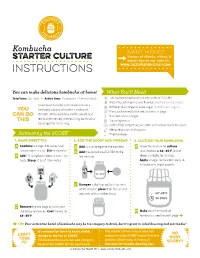

Instructions for Making Kombucha

Kombucha Want more? Dozens of eBooks, videos, & starter culture expert tips on our website: www.culturesforhealth.com Instructions m R You can make delicious kombucha at home! What You’ll Need Total time: 30+ days _ Active time: 15 minutes + 1 minute daily 1 dehydrated kombucha starter culture (SCOBY) Water free of chlorine and fluoride (bottled spring water) A kombucha starter culture consists of a sugar White or plain organic cane sugar (avoid harsh sugars) symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast you Plain, unflavored black tea, loose or in bags (SCOBY). When combined with sweetened can do Distilled white vinegar tea and fermented, the resulting kombucha this 1 quart glass jar beverage has a tart zing. Coffee filter or tight-weave cloth and rubber band to secure Measuring cups and spoons Activating the SCOBY Thermometer 1. make sweet tea 2. add the scoby and vinegar 3. culture your kombucha A Combine 2-3 cups hot water and G Allow the mixture to > >D Add 1/2 cup vinegar to the cool tea. > culture 1/4 cup sugar in a jar. Stir to dissolve. undisturbed at 68°-85°F, out of >E Add the dehydrated SCOBY to the B 11/2 teaspoons loose tea or 2 tea direct sunlight, for 30 days. > Add tea mixture. bags. Steep at least 10 minutes. Apply vinegar to the cloth daily to help prevent mold growth. sugar 1/2 1/4 c. c. 68°-85°F 2-3 c. 2 F Dampen a cloth or coffee filter with > white vinegar; place it on the jar and secure it with a rubber band. -

Teahouses and the Tea Art: a Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie Master's Thesis in East Asian Culture and History (EAST4591 – 60 Credits – Autumn 2015) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITY OF OSLO 24 November, 2015 © LI Jie 2015 Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie http://www.duo.uio.no Print: University Print Center, University of Oslo II Summary The subject of this thesis is tradition and the current trend of tea culture in China. In order to answer the following three questions “ whether the current tea culture phenomena can be called “tradition” or not; what are the changes in tea cultural tradition and what are the new features of the current trend of tea culture; what are the endogenous and exogenous factors which influenced the change in the tea drinking tradition”, I did literature research from ancient tea classics and historical documents to summarize the development history of Chinese tea culture, and used two month to do fieldwork on teahouses in Xi’an so that I could have a clear understanding on the current trend of tea culture. It is found that the current tea culture is inherited from tradition and changed with social development. Tea drinking traditions have become more and more popular with diverse forms. -

CEYLON TEA, the Journey - Sri Lanka - Part II - Guest Post by Linda Villano, Serendipitea

CEYLON TEA, The Journey - Sri Lanka - Part II - Guest Post by Linda Villano, SerendipiTea Monday, April 3rd 2017 @ 12:44 PM Continuing on from Part I, below are more highlights of my time spent with The Tea House Times on a trip to Sri Lanka . Since our return, numerous Ceylon tea focused posts appear through various channels of The Tea House Times: here in my personal blog, in Gail Gastelu’s blog, as well as in a focused feature blog for Sri Lanka. In addition, Ceylon Tea themed articles are featured in 2017 issues of The Tea House Times and will continue to be featured through August, the month marking big anniversary celebrations throughout Sri Lanka. So many photos were taken during this journey I feel a great need to share. Please make a pot of your favorite Ceylon tea, grab a cuppa and hop in a Tuk Tuk. Enjoy the voyage. BELOW *Ceylon Chamber of Commerce Colombo Tea Auction *Ceylon Chamber of Commerce Tea Facts * Colombo Tea Auction Catalog at the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce *Cuppa Milk Tea at the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce *ROADSIDE MARKET BioFoods Organic Tea Factory - Raw Material BioFoods Organic Tea Factory - Roller BioFoods Organic Tea Factory - Comparing Tea Grades BioFoods Organic Tea Factory - Hand Packing BioFoods Organic Tea Factory Cleaning Equipment Rack BioFoods Organic Tea Factory Green Tea & Garden Grown Banana *Unilever Instant Tea Factory Board Room *Unilever Instant Tea Factory *Sri Lanka Rupees ~ a day of leisure! *Bentota Beach Resort by Cinnamon A day of leisure! *Bentota Beach Resort Tea Samovar *Bentota Beach Resort Tea Cocktail & Tea Mocktail Menu *Bye Bye Sri Lanka & Thanks for the Memories! LEARN MORE Sri Lanka Tea Board Website: http://www.pureceylontea.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Sri-Lanka-Tea- Board/181010221960446 ~ Linda Villano, SerendipiTea . -

Notes on the History of Tea

Notes on the History of Tea It is surprising how incomplete our knowledge is. We are all aware that we import coffee from tropical America. But where do we obtain our tea? What is tea? From what plant does it come? How long have we been drinking it? All these questions passed through my mind as I read the manuscript of the pre- ceding article. To answer some of my questions, and yours, I gathered together the following notes. The tea of commerce consists of the more or less fermented, rolled and dried immature leaves of Camellia sinensis. There are two botanical varieties of the tea plant. One, var. sinensis, the original chinese tea, is a shrub up to 20 feet tall, native in southern and western Yunnan, spread by cultivation through- out southern and central China, and introduced by cultivation throughout the warm temperate regions of the world. The other, var. assamica, the Assam tea, is a forest tree, 60 feet or more tall, native in the area between Assam and southern China. Var. sinensis is apparently about as hardy as Camellia japonica (the common Camellia). The flowers are white, nodding, fra- grant, and produced variously from June to January, but usually in October. The name is derived from the chinese Te. An alter- nate chinese name seems to be cha, which passed into Hindi and Arabic as chha, anglicized at an early date as Chaw. The United States consumes about 115 million pounds of tea annually. The major tea exporting countries are India, Ceylon, Japan, Indonesia, and the countries of eastern Africa. -

Japanese Tea Ceremony: How It Became a Unique Symbol of the Japanese Culture and Shaped the Japanese Aesthetic Views

International J. Soc. Sci. & Education 2021 Vol.11 Issue 1, ISSN: 2223-4934 E and 2227-393X Print Japanese Tea Ceremony: How it became a unique symbol of the Japanese culture and shaped the Japanese aesthetic views Yixiao Zhang Hangzhou No.2 High School of Zhejiang Province, CHINA. [email protected] ABSTRACT In the process of globalization and cultural exchange, Japan has realized a host of astonishing achievements. With its unique cultural identity and aesthetic views, Japan has formed a glamorous yet mysterious image on the world stage. To have a comprehensive understanding of Japanese culture, the study of Japanese tea ceremony could be of great significance. Based on the historical background of Azuchi-Momoyama period, the paper analyzes the approaches Sen no Rikyu used to have the impact. As a result, the impact was not only on the Japanese tea ceremony itself, but also on Japanese culture and society during that period and after.Research shows that Tea-drinking was brought to Japan early in the Nara era, but it was not integrated into Japanese culture until its revival and promotion in the late medieval periods under the impetus of the new social and religious realities of that age. During the Azuchi-momoyama era, the most significant reform took place; 'Wabicha' was perfected by Takeno Jouo and his disciple Sen no Rikyu. From environmental settings to tea sets used in the ritual to the spirit conveyed, Rikyu reregulated almost all aspects of the tea ceremony. He removed the entertaining content of the tea ceremony, and changed a rooted aesthetic view of Japanese people.