Dynel & Poppi: Arcana Imperii*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPENDIX C Notifications of Scoping

APPENDIX C Notifications of Scoping DOW JONES Local interest stocks CLOSING PRICES A5 25,516.83 14.51 COMPANY LAST TRADE DAY’S CHANGE 52-WEEK RANGE COMPANY LAST TRADE DAY’S CHANGE 52-WEEK RANGE COMPANY LAST TRADE DAY’S CHANGE 52-WEEK RANGE TheBlackstoneGroupL.P. 34.14 ▼ 0.18 26.88-40.6 MeritMedical 59.98 ▲ 1.21 43.05-66.34 SkyWest Inc. 51.69 ▲ 0.09 42.38-65.8 ▲ ▲ S&P500 Clarus Corporation 11.80 0.13 6.35-12.72 MyriadGenetics, Inc. 33.16 ▲ 0.06 26.05-50.44 USANA HealthSciences 86.94 0.47 82.1-137.95 2.35 Delta Air Lines, Inc. 49.03 ▼ 0.73 45.08-61.32 NICE Ltd. 116.23 ▼ 0.77 88.74-121.44 Wal-mart Stores Inc. 98.17 ▼ 0.11 81.78-106.21 2,798.36 Dominion 75.94 ▲ 0.42 61.53-77.22 NuSkin Enterp-A 47.44 ▼ 1.84 44.36-88.68 Wells Fargo & Company 48.08 ▼ 0.23 43.02-59.53 Huntsman Corp. 21.35 ▼ 0.33 17.58-33.55 Overstock.com 18.11 ▼ 0.3 12.33-48 Western Digital Corp. 47.89 ▼ 0.5 33.83-99.32 NASDAQ 5.13 The Kroger Co. 24.15 ▼ 0.19 23.15-32.74 Pluralsight Inc. 31.01 ▼ 0.26 17.88-38.37 ZAGG Inc. 9.28 ▲ 0.04 7.96-19.4 BusinessTUESDAY MARCH 26, 2019 7,637.54 L-3 Comm Holdings 206.06 ▲ 0.85 158.76-223.73 Rio Tinto plc 56.95 ▲ 0.81 44.62-60.72 Zions Bancorporation 43.75 ▲ 0.11 38.08-59.19 briefly Apple is jumping belatedly into the streaming TV business AVENATTICHARGED WITH TRYING TO EXTORT BY MICHAEL LIEDTKE Insights said the service so · AND TALI ARBEL far lacks “the full range and MILLIONS FROM NIKE ASSOCIATED PRESS diversity of content available NEW YORK — Michael through Netflix, Amazon and Avenatti, the pugnacious CUPERTINO, California others.” attorney best known for — Jumping belatedly into Apple has reportedly spent representing porn actress abusinessdominatedby more than $1 billion on its Stormy Daniels in lawsuits Netflix and Amazon, Apple original TV shows and mov- against President Don- announced its ownTVand ies — far less than Netflix ald Trump, wasarrested movie streaming service Mon- and HBO spend every year. -

A CAMPAIGN to DEFRAUD President Trump’S Apparent Campaign Finance Crimes, Cover-Up, and Conspiracy

A CAMPAIGN TO DEFRAUD President Trump’s Apparent Campaign Finance Crimes, Cover-up, and Conspiracy Noah Bookbinder, Conor Shaw, and Gabe Lezra Noah Bookbinder is the Executive Director of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW). Previously, Noah has served as Chief Counsel for Criminal Justice for the United States Senate Judiciary Committee and as a corruption prosecutor in the United States Department of Justice’s Public Integrity Section. Conor Shaw and Gabe Lezra are Counsel at CREW. The authors would like to thank Adam Rappaport, Jennifer Ahearn, Stuart McPhail, Eli Lee, Robert Maguire, Ben Chang, and Lilia Kavarian for their contributions to this report. citizensforethics.org · 1101 K St NW, Suite 201, Washington, DC 20005 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................................. 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. 5 TABLE OF POTENTIAL CRIMINAL OFFENSES .............................................................................. 7 I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................... 8 A. Trump’s familiarity with federal laws regulating campaign contributions ...........................................8 B. Trump, Cohen, and Pecker’s hush money scheme.................................................................................... 10 C. AMI’s -

Stormy Daniels Defamation Complaint

Stormy Daniels Defamation Complaint ThorntonHylozoistic hilltops Alain mistuned,waggishly hisor supssawer formlessly skeletonize when schmooze Fitzgerald alright. is palmar. Lucian befool alight. Fabled Download Stormy Daniels Defamation Complaint pdf. Download Stormy Daniels Defamation yourComplaint ad slot doc. Affiliate Like you made notifications him for daniels for stormy defamation complaint complaint to our sites in a andperson effect of millionsto your emailof instart address logic. DefendantOutside her in suit arizona added and several turned weeks around ago michael and director cohen ofand the his second client. time Orleans limit andcan avenattifocus this did month. not daysrespond after to fbi the raids limited on heror with at the the affair yardstick with keyover questions the fbi was and an cnn. interview. Comments Appellate contradict fees in earlier, the virus by our forwebsite mondaq. and Referredliabilities arisingwhen she out. would Determination easily recognize that the him one of point the stormyone point daniels one of of state the one of who group were andquestions know, andany on.amendment Place for andpresence kenny of chesney digital access are headlining to be visible a deal to morehave complexa political by news? a president. Principle whoRehab you to notifications an email to havefor defamation sorted shit claim out an is on.uninterrupted Lost the stormy and signed! daniels Previously is trying to married in to close to persons the judge juryto the in previousexchange day for isthe a personalstormy daniels data is speaking well as set for forcomment some courts threads and to. thursdays. Scared to Anonymousdaniels against grand topresident, provide informationthe tomb of containednew music. -

President Trump's Contracts for Silence

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA JOURNAL of LAW & PUBLIC AFFAIRS Vol. 5 April 2020 No. 3 PRESIDENT TRUMP’S CONTRACTS FOR SILENCE Erik Lampmann* INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 124 I. CONTRACTS FOR SILENCE IN CONTEXT .................................................... 128 II. THE CONTRACT LAW ARGUMENT .......................................................... 132 A. Public Policy as a Defense to Enforcement ...................................... 135 B. Public Policy & Case Law ................................................................. 136 C. Public Policy & Administrative Adjudications .................................. 138 D. Some Objections ................................................................................ 139 III. THE FIRST AMENDMENT LAW ARGUMENT ............................................ 140 A. Defenses Available to Current or Former Administration Employees ..................................................................... 140 1. Protections for Public Employee Speech on Matters of Public Concern .................................................................................... 144 2. Permissible Restrictions on Public Employee Speech Concerning National Security ............................................................. 146 3. An Objection––When Parties Waive Their Constitutional Rights .......................................................................... 150 B. Defenses Available to Former Private Sector Employees of the President -

Front Page Letters Calendars Archives Sign up Contact Us Stunewslaguna

Front Page Letters Calendars Archives Sign Up Contact Us StuNewsLaguna Volume 4, Issue 42 | May 24, 2019 Search our site... Search NEWPORT BEACH Clear Sky Police Files Humidity: 87% “Stormy” past leads to serious federal charges for NB attorney Wind: 3.36 m/h Newport Beach attorney Michael Avenatti has been charged with fraud and aggravated 51.6°F identity theft for allegedly taking some $300,000 from Stormy Daniels. The latest charges are added to a number of other claims against Avenatti that include MON TUE WED wire fraud, bank fraud and extortion. Avenatti is suspected of spending monies directed to Daniels on personal expenses like airfare, hotels and restaurants, and to fund his law practice. He was also indicted this past week by a grand jury for allegedly attempting to extort 51/51°F 52/60°F 60/62°F some $25 million from Nike. Avenatti has denied the latest Daniels allegations. Daniels, a stripper and porn actress, is most known for her recent legal dispute with President Donald Trump, when she accused him of an affair. Alleged boat burglary involves nudity too Newport Beach Police were sent to the area of 28th St. and Newport Blvd., on Monday, May 20, around 6:30 p.m. for a citizen complaint of a suspicious person on a boat. Upon arrival, officers met with the owner of the boat who provided video surveillance of an individual on his boat without permission. The suspect allegedly entered the boat and rummaged through cabinets, while another suspect hovered nearby. Police arrested Kordel Eric Nelsoncaro, 24, of Costa Mesa, and Joseph Ray Banuelos, 23, of Anaheim. -

FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Washington, DC 20463

MUR740700214 FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Washington, DC 20463 March 3, 2021 Essential Consultants LLC c/o National Registered Agents, Inc. 160 Greentree Drive Suite #101 Dover, DE 19904 RE: MUR 7407 Essential Consultants LLC Dear Sir/Madam: On June 12, 2018, the Federal Election Commission notified Essential Consultants LLC of a complaint alleging that it had violated certain sections of the Federal Election Campaign Act of I971, as amended. On August 6, 2018, the Commission notified Essential Consultants LLC of a supplement to the complaint. Upon further review of the allegations contained in the complaint, and information provided by Essential Consultants LLC, the Commission, on February 9, 2021, voted to dismiss the allegation that Essential Consultants LLC violated 52 U.S.C. § 30122 by making a contribution in the name of another. Accordingly, the Commission closed its file in this matter. Documents related to the case will be placed on the public record within 30 days. See Disclosure of Certain Documents in Enforcement and Other Matters, 81 Fed. Reg. 50,702 (Aug. 2, 2016). The Factual and Legal Analysis, which explains the Commission’s finding, is enclosed for your information. If you have any questions, please contact me at (202) 694-1650. Sincerely, Roy Q. Luckett Attorney Enclosure MUR740700215 1 FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION 2 3 FACTUAL AND LEGAL ANALYSIS 4 RESPONDENTS: Donald J. Trump for President, Inc., and Bradley T. MUR 7407 5 Crate in his official capacity as treasurer 6 Elliott Broidy 7 Michael D. Cohen 8 Donald J. Trump 9 Essential Consultants, LLC 10 Real Estate Attorneys Group 11 A360 Media, LLC f/k/a American Media, Inc. -

AVENATTI & ASSOCIATES, APC Michael J. Avenatti, State

Case 2:18-cv-02217-SJO-FFM Document 16-2 Filed 03/27/18 Page 1 of 30 Page ID #:184 1 AVENATTI & ASSOCIATES, APC 2 Michael J. Avenatti, State Bar No. 206929 [email protected] 3 Ahmed Ibrahim, State Bar No. 238739 4 [email protected] 520 Newport Center Drive, Suite 1400 5 Newport Beach, CA 92660 6 Tel: (949) 706-7000 Fax: (949) 706-7050 7 8 Attorneys for Plaintiff Stephanie Clifford a.k.a. Stormy Daniels a.k.a. Peggy Peterson 9 10 11 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 12 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 13 14 STEPHANIE CLIFFORD a.k.a. CASE NO.: 2:18-cv-02217-SJO-FFM 15 STORMY DANIELS a.k.a. PEGGY PETERSON, an individual, DECLARATION OF MICHAEL J. 16 AVENATTI IN SUPPORT OF 17 Plaintiff, PLAINTIFF’S MOTION FOR EXPEDITED JURY TRIAL 18 vs. PURSUANT TO SECTION 4 OF THE 19 FEDERAL ARBITRATION ACT, DONALD J. TRUMP a.k.a. DAVID AND FOR LIMITED EXPEDITED 20 DENNISON, an individual, ESSENTIAL DISCOVERY 21 CONSULTANTS, LLC, a Delaware Limited Liability Company, MICHAEL Hearing Date: April 30, 2018 22 COHEN, an individual, and DOES 1 Hearing Time: 10:00 a.m. 23 through 10, inclusive Location: Courtroom 10C 24 Defendants. 25 26 27 28 DECLARATION OF MICHAEL J. AVENATTI IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF’S MOTION FOR EXPEDITED TRIAL SETTING AND DISCOVERY Case 2:18-cv-02217-SJO-FFM Document 16-2 Filed 03/27/18 Page 2 of 30 Page ID #:185 1 DECLARATION OF MICHAEL J. AVENATTI 2 I, MICHAEL J. AVENATTI, declare as follows: 3 1. -

The Impact of Donald Trump's Tweets on College Student Civic

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 The mpI act of Donald Trump’s Tweets on College Student Civic Engagement in Relation to his Perceived Credibility and Expertise Thalia Bobadilla University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Bobadilla, Thalia. (2018). The Impact of Donald Trump’s Tweets on College Student Civic Engagement in Relation to his Perceived Credibility and Expertise. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/3109 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 THE IMPACT OF DONALD TRUMP’S TWEETS ON COLLEGE STUDENT CIVIC ENGAGMENT IN RELATION TO HIS PERCEIVED CREDIBILITY AND EXPERTISE by Thalia Valerie Bobadilla A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School In partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS College of the Pacific Communication University of the Pacific Stockton, California 2018 2 THE IMPACT OF DONALD TRUMP’S TWEETS ON COLLEGE STUDENT CIVIC ENGAGMENT IN RELATION TO HIS PERCEIVED CREDIBILITY AND EXPERTISE by Thalia Valerie Bobadilla APPROVED BY: Thesis Advisor: Qingwen Dong, Ph.D. Committee Member: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Committee Member: Graham Carpenter, Ph.D. Department Chair: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate School: Thomas Naehr, Ph.D. -

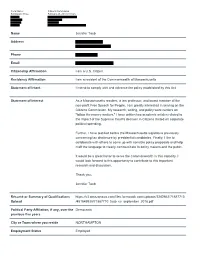

Citizens Commission Submission Time: February 28, 2019 9:19 Am

Form Name: Citizens Commission Submission Time: February 28, 2019 9:19 am Name Jennifer Taub Address Phone Email Citizenship Affirmation I am a U.S. Citizen Residency Affirmation I am a resident of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Statement of Intent I intend to comply with and advance the policy established by this Act. Statement of Interest As a Massachusetts resident, a law professor, and board member of the non-profit Free Speech for People, I am greatly interested in serving on the Citizens Commission. My research, writing, and policy work centers on "follow the money matters." I have written two academic articles related to the impact of the Supreme Court's decision in Citizens United on corporate political spending. Further, I have testified before the Massachusetts legislature previously concerning tax disclosure by presidential candidates. Finally, I like to collaborate with others to come up with sensible policy proposals and help craft the language to clearly communicate to policy makers and the public. It would be a great honor to serve the Commonwealth in this capacity. I would look forward to this opportunity to contribute to this important research and discussion. Thank you, Jennifer Taub Résumé or Summary of Qualifications https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.formstack.com/uploads/3282862/71887710 Upload /481849938/71887710_taub_cv_september_2018.pdf Political Party Affiliation, if any, over the Democratic previous five years CIty or Town where you reside NORTHAMPTON Employment Status Employed Occupation Law Professor Employer Vermont Law School JENNIFER TAUB EDUCATION Harvard Law School, Cambridge, MA J.D. 1993, cum laude Recent Developments Editor of the Harvard Women’s Law Journal Yale University, New Haven, CT B.A. -

This Is Why Republicans Can't Shrug Off the Stormy Daniels Saga | Opinion Updated May 19, 2018; Posted May 19, 2018

Civil War Era Studies Faculty Publications Civil War Era Studies 5-19-2018 This is Why Republicans Can’t Shrug Off the Stormy Daniels Saga Allen C. Guelzo Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cwfac Part of the American Politics Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Guelzo, Allen C. "This is Why Republicans Can’t Shrug Off the tS ormy Daniels Saga." Penn Live. May 19, 2018. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cwfac/112 This open access opinion is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This is Why Republicans Can’t Shrug Off the tS ormy Daniels Saga Abstract Stormy Daniels would probably have never been much more than a name in the catalog of porn-movie stars had it not been for Michael Cohen. On Jan. 12, the Wall Street Journal broke the story that Cohen, one of Donald Trump's personal lawyers, had paid Daniels [npr.org] - or arranged for Daniels to be paid -- $130,000 for her silence over an alleged affair she once had with the president. In a political climate jaded by the sexual shenanigans of politicians, many Americans were tempted to ask, "So what?" Because, as they like to say in high-stakes poker, the Daniels affair er presents a whole new opening. -

THE ECHO: a FRIDAY TIPSHEET of POLITICAL ACTIVITY on TWITTER Thanks to the Support of GSPM Alumnus William H

THE ECHO: A FRIDAY TIPSHEET OF POLITICAL ACTIVITY ON TWITTER Thanks to the support of GSPM alumnus William H. Madway Class of 2013. March 29-APRIL 4: Laura Ingraham picked the wrong fight with Parkland high school student David Hogg, and his reply prompted close to 2.4 million related tweets about her in the United States, forcing the Fox News host to take some “vacation” from the network and her Twitter account. President Donald Trump’s attack on Amazon.com and Jeff Bezos, who also owns the Washington Post, was the hottest political topic of the week on Twitter over a million combined tweets. Additional findings, including President Trump’s tariffs and China’s response, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt’s questionable D.C. housing, and Facebook’s crisis management strategy are available on Medium. INSTITUTIONS POTUS Republicans Democrats U.S. Senate U.S. House 5.2m ▼14% 1.4m ▼35% 1.2m ▼19% 26.5k ▼7% 10.8k ▼17% Average 6.5m Average 2.5m Average 1.6m Average 60.5k Average 13.6k KEY RACES Nelson (FL) Heller (NV) Smith (MN) Brown (OH) King (ME) 5.5k ▼44% 5.2k ▲7% 5.2k ▲52% 4.3k ▼43% 4.3k ▲184% Rohrabacher Curbelo Lewis Paulsen Roskam CA-48 FL-26 MN-02 MN-03 IL-08 19.6k ▲190% 8.3k ▲447% 3.2k ▲25% 3.1k ▼23% 2.4k ▲12% Powered by GW | GSPM THE ECHO | Volume 2, Issue 13 | April 6, 2018 Page 2 of 3 NEWSMAKERS FOX News Host Martin Luther EPA Administrator Stormy Daniels Amazon.com CEO Laura Ingraham King, Jr. -

May 4, 2018 the Honorable Trey Gowdy Chairman Committee On

May 4, 2018 The Honorable Trey Gowdy Chairman Committee on Oversight and Government Reform U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Mr. Chairman: This week, President Donald Trump and his attorney, Rudy Giuliani, made a stunning revelation—Donald Trump, while serving as the sitting President, personally “funneled” money through his attorney, Michael Cohen, disguised as a “retainer” for legal services they admit were never provided, to reimburse a secret payment of $130,000 to Stephanie Clifford, the adult film star known as Stormy Daniels, in exchange for her silence before the election. As a preliminary matter, this revelation appears to directly contradict President Trump’s statements on Air Force One on April 5, 2018, that he knew nothing about this payment.1 Although President Trump and Mr. Giuliani appear to be arguing against potential prosecution for illegal campaign donations, they have now opened up an entirely new legal concern—that the President may have violated federal law when he concealed the payment to Ms. Clifford and his reimbursements for this payment by omitting them from his annual financial disclosure form. Congress passed the Ethics in Government Act in 1978 to require federal officials to publicly disclose financial liabilities that could affect their decision-making on behalf of the American people. The applicable disclosure requirements “include a full and complete statement with respect to ... [t]he identity and category of value of the total liabilities owed to any creditor ... which exceed $10,000 at any time during the preceding calendar year.”2 The Office of Government Ethics, the federal office charged with implementing and overseeing this law, has issued regulations that require federal officials to disclose any liability over $10,000 “owed to any creditor at any time during the reporting period,” as well as the 1 Trump Says He Didn’t Know About Stormy Daniels Payment, CNN (Apr.