Class 6: Two Views of Verdi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ildar Abdrazakov Las Versiones Del Demonio

ENTREVISTA Ildar Abdrazakov Las versiones del demonio por Ingrid Haas ldar Abdrazakov es uno de los grandes bajos en la actualidad. A sus 39 años, goza ya de una carrera sólida y llena de éxitos en teatros tan importantes como la Scala de Milán, Iel Metropolitan Opera House de Nueva York, Washington Opera, Los Ángeles Ópera, Royal Opera House de Londres, Opéra Bastille de París, el Teatro Mariinsky, el Liceu de Barcelona, el Real de Madrid, la Ópera de Montecarlo, la Ópera de San Francisco, la Ópera Estatal de Viena y la Ópera Estatal de Baviera, entre otras. La voz de Abdrazakov ha conquistado a los públicos más exigentes y a directores de orquesta de la talla de Riccardo Muti, James Levine, Valery Gergiev, Gianandrea Noseda, Anthony Pappano, Riccardo Chailly y Bertrand de Billy, sólo por nombrar a algunos. “En las tres Con su cavernoso timbre, innegable musicalidad y gallarda versiones de presencia escénica, Abdrazakov ha cantado una amplia gama de Mefistófeles que he roles que van desde Fígaro en Le nozze di Figaro de Mozart, el rol cantado, mi Fausto titular y Leporello en Don Giovanni, Moïse en Moïse et Pharaon, ha sido siempre Assur en Semiramide, Don Basilio en Il Barbiere di Siviglia, las Ramón Vargas” tres de Rossini, Oroveso en Norma de Bellini, Méphistophélès Foto: Sergei Misenko en las versiones de Faust de Gounod y La damnation de Faust de Berlioz, el rol principal de Mefistofelede Boito, los Cuatro Sí, en efecto. Vine a cantar hace unos años a la Ciudad de México: Villanos de Les contes d’Hoffmann, Walter en Luisa Miller así un recital en la Sala Nezahualcóyotl y el Requiem de Verdi en como Oberto y Attila en las óperas homónimas de Verdi, Dosifei en Bellas Artes. -

Ildar Abdrazakov

POWER PLAYERS Russian Arias for Bass ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV CONSTANTINE ORBELIAN, CONDUCTOR KAUNAS CITY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA KAUNAS STATE CHOIR 1 0 13491 34562 8 ORIGINAL DELOS DE 3456 ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV • POWER PLAYERS DIGITAL iconic characters The dynamics of power in Russian opera and its most DE 3456 (707) 996-3844 • © 2013 Delos Productions, Inc., © 2013 Delos Productions, 95476-9998 CA Sonoma, 343, Box P.O. (800) 364-0645 [email protected] www.delosmusic.com CONSTANTINE ORBELIAN, CONDUCTOR ORBELIAN, CONSTANTINE ORCHESTRA CITY SYMPHONY KAUNAS CHOIR STATE KAUNAS Arias from: Arias Rachmaninov: Aleko the Tsar & Ludmila,Glinka: A Life for Ruslan Igor Borodin: Prince Boris GodunovMussorgsky: The Demon Rubinstein: Onegin, Iolanthe Eugene Tchaikovsky: Peace and War Prokofiev: Rimsky-Korsakov: Sadko 66:49 Time: Total Russian Arias for Bass ABDRAZAKOV ILDAR POWER PLAYERS ORIGINAL DELOS DE 3456 ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV • POWER PLAYERS DIGITAL POWER PLAYERS Russian Arias for Bass ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV 1. Sergei Rachmaninov: Aleko – “Ves tabor spit” (All the camp is asleep) (6:19) 2. Mikhail Glinka: Ruslan & Ludmila – “Farlaf’s Rondo” (3:34) 3. Glinka: Ruslan & Ludmila – “O pole, pole” (Oh, field, field) (11:47) 4. Alexander Borodin: Prince Igor – “Ne sna ne otdykha” (There’s no sleep, no repose) (7:38) 5. Modest Mussorgsky: Boris Godunov – “Kak vo gorode bylo vo Kazani” (At Kazan, where long ago I fought) (2:11) 6. Anton Rubinstein: The Demon – “Na Vozdushnom Okeane” (In the ocean of the sky) (5:05) 7. Piotr Tchaikovsky: Eugene Onegin – “Liubvi vsem vozrasty pokorny” (Love has nothing to do with age) (5:37) 8. Tchaikovsky: Iolanthe – “Gospod moi, yesli greshin ya” (Oh Lord, have pity on me!) (4:31) 9. -

Marco Boemi Conductor Website

Straussengasse 14 /1 1050 Vienna – Austria Ivan Paley: [email protected] Stefan Astner: [email protected] Marco Boemi Conductor Website: www.viemuc.com Marco Boemi is a conductor and pianist who also graduated law at the Sapienza University of Rome. He performed at the Rome Opera, Teatro alla Scala Milan, The Teatro Regio in Turin, Suntory Hall Tokyo, Bayerische Staatsoper, Wiener Musikverein, Paris Opera Bastille and many other major venues. His extensive symphonic and operatic repertoire includes authors like Verdi, Puccini, Beethoven, Mahler, Wagner, Ravel, Saint-Saëns, Debussy, Rachmaninov, Gershwin and Bernstein. During his, more than 20 years long, career he cooperated with many notable singers, such as Pavarotii, Taddei, Kabaivanska, Netrebko, Obratzova, Gruberova, Borodina, Shicoff, Bruson, Ricciarelli, Burchuladze, Abdrazakov and others and also conducted London Philhamonic Orchestra, all the major Japanese orchestras, World Youth Orchestra, Verdi Orchestra and many others. He gives masterclasses for young pianists, singers and conductors and is considered an expert in Lied music. He has recorded for Decca, TDK, Universal with artist such as Colombara, La Scola, Sabbatini, Armiliato and Dessì. In the year 2013 he conducted Verdi´s “Atilla” for the world opening of the Astana Opera. Later on, a Gala concert with Ildar Abdrazakov at the Royal Opera House Muscat, a Gala concert with Netrebko in Kazan, “La traviata” in Verona, “Il trovatore” in Treviso, “Turandot” in Bogotá, as well as “Don Pasquale” in Helsinki were conducted by Boemi. In April 2016, he has again conducted a Gala concert with © Gianni Netrebko and Eyvazov in Los Angeles. Other highlights of the last seasons include “Aida” in Livorno, Pisa and Rovigo, “Il tabarro / I Pagliacci” in Helsinki, “Nabucco” in Lima and “Porgy and Bess” at the Tatar State Opera in Kazan. -

03-10-2018 Semiramide Mat.Indd

GIOACHINO ROSSINI semiramide conductor Opera in two acts Maurizio Benini Libretto by Gaetano Rossi, based on production John Copley the play Sémiramis by Voltaire set designer Saturday, March 10, 2018 John Conklin 1:00–4:40 PM costume designer Michael Stennett lighting designer John Froelich revival stage director The production of Semiramide was Roy Rallo made possible by a generous gift from the Lila Acheson and DeWitt Wallace Fund for Lincoln Center, established by the founders of The Reader’s Digest Association, Inc. The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from Ekkehart Hassels-Weiler general manager Peter Gelb music director designate Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2017–18 SEASON The 34th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIOACHINO ROSSINI’S This performance semiramide is being broadcast live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Opera conductor International Radio Maurizio Benini Network, sponsored in order of vocal appearance by Toll Brothers, America’s luxury oroe, high priest of the magi ® homebuilder , with Ryan Speedo Green* generous long-term support from idreno, an indian prince The Annenberg Javier Camarena Foundation, The Neubauer Family assur, a prince Foundation, the Ildar Abdrazakov Vincent A. Stabile Endowment for semir amide, queen of babylon Broadcast Media, Angela Meade and contributions from listeners arsace, commander of the assyrian army worldwide. Elizabeth DeShong There is no Toll Brothers– a zema, a princess Metropolitan Sarah Shafer Opera Quiz in List Hall today. mitr ane, captain of the guard Kang Wang** This performance is also being broadcast ghost of king nino live on Metropolitan Jeremy Galyon Opera Radio on SiriusXM channel 75. -

09-25-2019 Macbeth.Indd

GIUSEPPE VERDI macbeth conductor Opera in four acts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave production Adrian Noble and Andrea Maffei, based on the play by William Shakespeare set and costume designer Mark Thompson Wednesday, September 25, 2019 lighting designer 8:00–11:10 PM Jean Kalman choreographer Sue Lefton First time this season The production of Macbeth was made possible by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Paul M. Montrone Additional funding was received from Mr. and Mrs. William R. Miller; Hermione Foundation, Laura Sloate, Trustee; and The Gilbert S. Kahn & John J. Noffo Kahn Endowment Fund Revival a gift of Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2019–20 SEASON The 106th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S macbeth conductor Marco Armiliato in order of appearance macbeth fle ance Plácido Domingo Misha Grossman banquo a murderer Ildar Abdrazakov Richard Bernstein l ady macbeth apparitions Anna Netrebko a warrior Christopher Job l ady-in-waiting Sarah Cambidge DEBUT a bloody child Meigui Zhang** a servant DEBUT Bradley Garvin a crowned child duncan Karen Chia-Ling Ho Raymond Renault DEBUT a her ald malcolm Yohan Yi Giuseppe Filianoti This performance is being broadcast a doctor macduff live on Metropolitan Harold Wilson Matthew Polenzani Opera Radio on SiriusXM channel 75. Wednesday, September 25, 2019, 8:00–11:10PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Macbeth Assistants to the Set Designer Colin Falconer and Alex Lowde Assistant to the Costume Designer Mitchell Bloom Musical Preparation John Keenan, Yelena Kurdina, Bradley Moore*, and Jonathan C. -

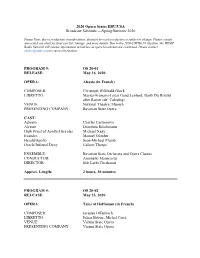

2020 Opera Series EBU/USA Broadcast Schedule —Spring/Summer 2020

2020 Opera Series EBU/USA Broadcast Schedule —Spring/Summer 2020 Please Note: due to production considerations, duration for each production is subject to change. Please consult associated cue sheet for final cast list, timings, and more details. Due to the 2020 COVID-19 situation, the WFMT Radio Network will release information in batches as opera broadcasts are confirmed. Please contact [email protected] for more information. PROGRAM #: OS 20-01 RELEASE: May 16, 2020 OPERA: Alceste (in French) COMPOSER: Christoph Willibald Gluck LIBRETTO: Marius-François-Louis Gand Lebland, Bailli Du Roullet after Ranieri de’ Calzabigi VENUE: National Theatre, Munich PRESENTING COMPANY: Bavarian State Opera CAST: Admeto Charles Castronovo Alceste Dorothea Röschmann High Priest of Apollo/Hercules Michael Nagy Evandro Manuel Günther Herald/Apollo Sean Michael Plumb Oracle/Infernal Deity Callum Thorpe ENSEMBLE: Bavarian State Orchestra and Opera Chorus CONDUCTOR: Antonello Manacorda DIRECTOR: Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui Approx. Length: 2 hours, 30 minutes PROGRAM #: OS 20-02 RELEASE: May 23, 2020 OPERA: Tales of Hoffmann (in French) COMPOSER: Jacques Offenbach LIBRETTO: Juless Babier, Michel Carré VENUE: Vienna State Opera PRESENTING COMPANY : Vienna State Opera CAST: Hoffmann Dmitry Korchak Olympia/Antonia/Giulietta Olga Peretyatko The Muse/Nicklausse Gaëlle Arquez Councillor Lindorf/Coppélius/ Luca Pisaroni Miracle/ Dapertutto Andrès/Cochenille/Frantz/ Michael Laurenz Pitichinaccio ENSEMBLE: Vienna State Opera Chorus and Orchestra CONDUCTOR: Frédéric Chaslin DIRECTOR: Andrei Serban Approx. Length: 2 hours, 30 minutes PROGRAM #: OS 20-03 RELEASE: May 30, 2020 OPERA: Elektra (in German) COMPOSER: Richard Strauss LIBRETTO: Hugo von Hofmannsthal VENUE: Vienna State Opera PRESENTING COMPANY : Vienna State Opera CAST: Klytaemnestra Waltraud Meier Elektra Christine Goerke Chrysothemis Simone Schneider Aegisth Norbert Ernst Orest Michael Volle ENSEMBLE: Vienna State Opera Orchestra CONDUCTOR: Semyon Bychkov DIRECTOR: Uwe Eric Laufenberg Approx. -

Lucia Di Lammermoor GAETANO DONIZETTI MARCH 3 – 11, 2012

O p e r a B o x Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .9 Reference/Tracking Guide . .10 Lesson Plans . .12 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .44 Flow Charts . .49 Gaetano Donizetti – a biography .............................56 Catalogue of Donizetti’s Operas . .58 Background Notes . .64 Salvadore Cammarano and the Romantic Libretto . .67 World Events in 1835 ....................................73 2011–2012 SEASON History of Opera ........................................76 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .87 così fan tutte WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART The Standard Repertory ...................................91 SEPTEMBER 25 –OCTOBER 2, 2011 Elements of Opera .......................................92 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................96 silent night KEVIN PUTS Glossary of Musical Terms . .101 NOVEMBER 12 – 20, 2011 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .105 werther Evaluation . .108 JULES MASSENET JANUARY 28 –FEBRUARY 5, 2012 Acknowledgements . .109 lucia di lammermoor GAETANO DONIZETTI MARCH 3 – 11, 2012 madame butterfly mnopera.org GIACOMO PUCCINI APRIL 14 – 22, 2012 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 Kevin Ramach, PRESIDENT AND GENERAL DIRECTOR Dale Johnson, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Educator, Thank you for using a Minnesota Opera Opera Box. This collection of material has been designed to help any educator to teach students about the beauty of opera. This collection of material includes audio and video recordings, scores, reference books and a Teacher’s Guide. The Teacher’s Guide includes Lesson Plans that have been designed around the materials found in the box and other easily obtained items. In addition, Lesson Plans have been aligned with State and National Standards. -

Opera Productions Old and New 6. Two Views of Verdi: Aïda /Attila

was halted by a combination of famine and delaying tactics by the Roman army, though Church tradition assigns most of the credit to Opera Pope Leo I, who met with the invader near Mantua and persuaded him into a treaty. The subject had a political resonance for Verdi’s Productions contemporaries as Northern Italy was then under the rule of Austria. But it has less resonance us today. The Huns left little or no art or Old and New achitecture, making it hard for us to imagine their world, and our knowledge of the Roman empire is mostly of an earlier period. La Scala opened its 2018–19 season with a new production of Attila by Davide Livermore that looks to our own time for relevance: to all those news photos (and in some cases memories) of wartime destruction and occupation from WW2 to Yugoslavia. It is not a consistent approach, as we shall see, but it is never less than interesting. Verdi: Attila.La Scala, Milan, 2018. Saioa Hernández (Odabella), Fabio Sartori (Foresto), George Petean (Ezio), Ildar Abdrazakov (Attila), Gianluca Buratto (Leone); c. Riccardo Chailly; d. Davide Livermore; des. Giò Forma . After a glimpse of a more conventional staging from St. Petersburg, we shall look at two substantial scenes from La Scala, plus some shorter excerpts. The first is the Prologue. Attila has just conquered the city of Aquileia and is surprised that some female inhabitants have been left alive. The resistance fighter Odabella pours scorn on the Huns who leave their women quietly at home. Her attitude intrigues Attila. -

Classical New York 2.0 Published on Iitaly.Org (

Classical New York 2.0 Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) Classical New York 2.0 Julian Sachs (November 01, 2010) For our first piece of this season, the ups and downs of the first month of operas at the Met. Plus, what we can look forward to in November. On September 27 the 2010-2011 Metropolitan Opera [2] season began with a new production of Richard Wagner’s Das Rheingold. The following night the Teutonic fogs were dispelled by the reprise of last season’s production of Offenbach’s Les Contes d’Hoffmann. Twenty-one hours later the audience was present for Verdi’s Rigoletto. Less than two weeks went by and a new production of Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov premiered, followed five days later by Zeffirelli’s immortal production of Puccini’s La Bohème. Such a contrasting and multi-flavored operatic feast is enough to give any critic indigestion, so what follows is a few glimpses at the ups and downs of these five productions of early 2010. UP: James Levine, the singers, and his orchestra, Das Rheingold. Page 1 of 4 Classical New York 2.0 Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) This season is in his honor, because it marks the 40th anniversary of his Met debut, and 35th from his appointment as Music Director. Under his guide the orchestra always sounds better, and the general improvement in quality over the years has been felt by every assiduous Met-goer, resulting in the Met orchestra becoming arguably the best opera-house orchestra in the world. -

02-20-2019 Don Giovanni Eve.Indd

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART don giovanni conductor Opera in two acts Cornelius Meister Libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte production Michael Grandage Wednesday, February 20, 2019 PM set and costume designer 7:30–11:00 Christopher Oram lighting designer Paule Constable choreographer Ben Wright revival stage director Louisa Muller The production of Don Giovanni was made possible by a generous gift from the Richard and Susan Braddock Family Foundation, and Sarah and Howard Solomon Additional funding was received from Jane and Jerry del Missier and Mr. and Mrs. Ezra K. Zilkha The revival of this production is made possible general manager by a gift from the Metropolitan Opera Club Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 571st Metropolitan Opera performance of WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART’S don giovanni conductor Cornelius Meister in order of vocal appearance leporello continuo Ildar Abdrazakov Kari Jane Docter, cello Howard Watkins*, donna anna harpsichord Jennifer Check* mandolin solo don giovanni Joyce Rasmussen Balint Luca Pisaroni the commendatore Štefan Kocán don ot tavio Stanislas de Barbeyrac donna elvir a Federica Lombardi zerlina Rihab Chaieb* maset to Peixin Chen Wednesday, February 20, 2019, 7:30–11:00PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA A scene Chorus Master Donald Palumbo from Mozart’s Musical Preparation Gregory Buchalter, Howard Watkins*, Don Giovanni Lydia Brown*, and Nimrod David Pfeffer* Fight Director J. Allen Suddeth Assistant Stage Directors Sarah Ina Meyers and Daniel Rigazzi Stage Band Conductor Jeffrey Goldberg Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Nimrod David Pfeffer* Met Titles Cori Ellison Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Das Gewand, Düsseldorf, and Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses fire effects. -

Donizetti Resources

GAETANO DONIZETTI RESOURCES Books Donizetti and His Operas (Cambridge Paperback Library) Author: William Ashbrook. This original monograph about Donizetti is published in paperback. Cambridge University Press. 1983. Gaetano Donizetti : A Guide to Research (Composer Resource Manuals, Volume 51) Author: James P. Cassaro. This hardcover research and information guide offers an annotated reference guide to the life and works of this important Italian opera composer. The book includes a complete chronology of Donizetti's life (1797-1848) and career, secondary resources and other works, including general sources, catalogs, correspondence, biographical sources, critical works; production/review sources, singers and theaters, and the individual operas. Routledge. 2000. Gaetano Donizetti: A Research and Information Guide (Routledge Music Bibliographies) Author: James P. Cassaro. This hardcover research and information guide offers an annotated reference guide to the life and works of this important Italian opera composer. The book opens with a complete chronology of Donizetti's life (1797-1848) and career. The balance of the book details secondary resources and other works, including general sources, catalogs, correspondence, biographical sources, critical works; production/review sources, singers and theaters, and the individual operas. Routledge. 2009. SAN FRANCISCO OPERA Education Materials GAETANO DONIZETTI Resources Film/DVDs SF Opera: Opera in an Hour / Donizetti’s The Elixir of Love (2008) These one-hour versions of San Francisco Opera performances are FREE for all Bay Area educators to use in their classrooms. Sung in English with English subtitles. http://sfopera.com/discover-opera/education- programs/for-schools/opera-in-an-hour-movies/ Preview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JAsBDVHkSDI Gaetano Donizetti - L'Elisir d'Amore / Netrebko, Villazon, Schenk, Eschwé, Wiener Staatsoper (2005) Actors: Rolando Villazon, Anna Netrebko, Ildebrando d'Arcangelo, Leo Nucci, Alfred Eschwé. -

Verdi Rigoletto

VERDI ◆ RIGOLETTO DMITRI HVOROSTOVSKY DE 3522 NADINE SIERRA FRANCESCO DEMURO ANDREA MASTRONI OKSANA VOLKOVA CONSTANTINE ORBELIAN, conductor DELOS DE DELOS DE GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813-1901) RIGOLETTO 3522 3522 RIGOLETTO, the Duke’s jester: Dmitri Hvorostovsky, baritone GILDA, his daughter: Nadine Sierra, soprano THE DUKE OF MANTUA: Francesco Demuro, tenor VERDI SPARAFUCILE, an assassin: Andrea Mastroni, bass VERDI MADDALENA, his sister: Oksana Volkova, contralto ◆ ◆ RIGOLETTO Kaunas City Symphony Orchestra RIGOLETTO Men of the Kaunas State Choir Constantine Orbelian, conductor CD 1 (1–18) Total Time: 59:28 CD 2 (1–22) Total Time: 67:36 ORIGINAL ORIGINAL DIGITAL DIGITAL Special thanks go to Algimantas Treikauskas, General Director of the Kaunas City Symphony Orchestra— GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813-1901) as well as his staff—for their invaluable help in producing this recording. Also much appreciated are the invaluable contributions of Artistic Consultant John Fisher and pianist/ RIGOLETTO vocal coach Svetlana Efimova. Opera in three acts Recorded at Kaunas Philharmonic July 1–9, 2016 Libretto: Francesco Maria Piave, after the Producers: Vilius Keras and Aleksandra Kerienė play Le roi s’amuse by Victor Hugo Recording Engineer: Vytautas Kederys Editing/mastering: Vilius Keras and Aleksandra Kerienė Program notes and synopsis: Lindsay Koob RIGOLETTO, the Duke’s jester: MATTEO BORSA, a courtier: Booklet editors/proofers: Lindsay Koob, Anne Maley, David Brin Dmitri Hvorostovsky, baritone Tomas Pavilionis, tenor Art Design/Layout: Lonnie Kunkel Photo Credits: