Cognitive Studies in Literature and Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

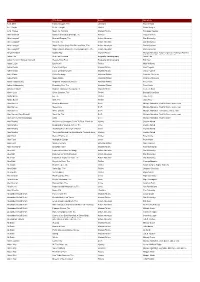

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

Little Angel Theatre Announces Macbeth Soundtrack Casting

Little Angel Theatre, 14 Dagmar Passage, London N1 2DN www.littleangeltheatre.com / Box Office 020 7226 1787 PRESS RELEASE: LITTLE ANGEL THEATRE ANNOUNCES MACBETH SOUNDTRACK CASTING A group of extraordinary actors are joining Little Angel Theatre to record the soundtrack of its puppetry production of MACBETH. The stunning visual imagery of the production’s puppetry will be matched by a world class vocal soundtrack, which opens for previews on 5th October (press show 10th October, 7.30pm). The role of Macbeth will be played by Nathaniel Parker, recently seen in the West End production of The Audience, starring Dame Helen Mirren, and well-known for his role in the BBC’s Inspector Lynley Mysteries. Nathaniel began his career at the RSC and returns to them for their 2013 winter season. Award-winning actress Helen McCrory will play the part of Lady Macbeth. Helen has had a wide career in theatre, film and TV, including a 2006 Olivier Award nomination for her role in As You Like It. In the same year she also appeared as Cherie Blair in the film The Queen. In 2012 she appeared in The Last of the Haussmans at the National Theatre, and has been seen recently in the James Bond film Skyfall and as Narcissa Malfoy in the Harry Potter films. Donald Sumpter will play the part of King Duncan, drawing on considerable previous Shakespearean experience in roles such as Claudius (Hamlet at Young Vic) and Marcus Andronicus (Titus Andronicus for the RSC). TV viewers will know him from his role as Kemp in Being Human and Maester Luwin in the HBO series Game of Thrones. -

Theatregraphy

Theatregraphy Play Company Year Date Theatre Co Stars Director Author Richard III National 1981 nn nn nn nn Youth Theatre Macbeth National 1982 nn nn Sally Dexter nn (as Macbeth) Youth Theatre Trumpets and Drums (based on London 1984 nn nn nn Berthold The Recruiting Officer) Academy of Brecht (as Captain Brazen) Music and Dramatic Art Claw Theatre 1985 nn Theatre Clwyd / nn nn nn (as Lusby) Clwyd / Mold Mold Trumpets and Drums (based on Theatre 1985 nn Theatre Clwyd / nn nn Berthold The Recruiting Officer) Clwyd / Mold Mold Brecht (as Captain Brazen) Romeo and Juliet (as Tybalt) Young Vic, 1986 11.02.1986 - Old Vic Vincenzo Ricotta, David William London ??? Mike Shannon, Rob Thacker Shakespeare Edwards, Paul Bradley, Geoffrey Beavers, Edward York, Gary Lucas, Sharon Bower, Suzan Sylvester, Val McLane, Gary Cady, Leslie Southwick, John Hallam The Winter's Tale (as Florizel) RSC 1986 25.05.1986 – Royal Terry Hands William Raymond Bowers, 17.01.1987 Shakespeare Shakespeare Gillian Barge, 14.10.1987 - Theatre Eileen Page, ??? Jeremy Irons, Stanley Dawson, Penny Downie, Paul Greenwood, Joe Melia, Sean O'Callaghan, Henry Goodman, Mark Lindley, Cornelia Hayes, Caroline Johnson, Susie Fairfax, David Glover, Brian Lawson, Bernard Horsfall, Simon Russell Beale, Roger Watkins, Trevor Gordon, Gary Love, Roger Moss, Patrick Robinson, Martin Hicks, Richard Parry, Sam Irons, Richard Easton Every Man in His Humour RSC 1986 15.05.1986 – Swan Theatre Haig, David Caird, John Jonson, Ben (as Wellbred) 07.01.1987 Richardson, Joely Postlethwaite, Pete Moss, -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

Bamcinématek Presents Queer Pagan Punk: the Films of Derek Jarman, Oct 30—Nov 11

BAMcinématek presents Queer Pagan Punk: The Films of Derek Jarman, Oct 30—Nov 11 A complete retrospective of Jarman’s 12 feature films, the most comprehensive New York series in nearly two decades New restorations of debut feature Sebastiane and Caravaggio “It feels like the correct time to be reminded of an ancient tradition that has always served civilization well, that of the independent, truth-telling poet provocateur.”—Tilda Swinton The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Brooklyn, NY/Sep 30, 2014—From Thursday, October 30 through Tuesday, November 11, BAMcinématek presents Queer Pagan Punk: The Films of Derek Jarman, a comprehensive retrospective of iconoclastic British filmmaker and crusading gay rights activist Derek Jarman, following its run at the BFI this spring. Jarman not only redefined queer cinema, but reimagined moviemaking as a means for limitless personal expression. From classical adaptations to historical biographies to avant-garde essay films, he crafted a body of work that was at once personal and political, during a difficult period when British independent cinema was foundering and the AIDS crisis provoked a wave of panic and homophobia. Also a poet, diarist, and painter, Jarman first entered the realm of the movies as a production designer for Ken Russell. The Devils (1971—Oct 31), Russell’s controversial opus of repressed nuns and witchcraft trials, played out in a 17th-century French village that Jarman spent a year creating. His own first feature, Sebastiane (1976—Nov 9), playing in a new restoration, placed a daring emphasis on male nudity and eroticism as it chronicled the death of the Christian martyr; Jarman called it “the first film that depicted homosexuality in a completely matter-of-fact way.” A time-traveling Queen Elizabeth I wanders among the ruins of a dystopic modern London in Jubilee (1978—Oct 30), a shot-in-the-streets survey of the burgeoning punk scene that captures early performances by Adam Ant, Wayne County, Siouxsie and the Banshees, and the Slits. -

Rough Draft: a Film by Caitlin Clements

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2011 Rough Draft: A Film by Caitlin Clements Caitlin Skelly Clements College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Clements, Caitlin Skelly, "Rough Draft: A Film by Caitlin Clements" (2011). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 413. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/413 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scriptwriting: Theory and Practice The independent study course which I hope to participate in this semester would involve writing a twenty to thirty-page screenplay that would eventually be produced into a short film. This film would be made as an Honors Project using the funding for a self-designed project, which is provided as a facet of the Murray Scholar Program. The Independent Study would be advised by Professor Sharon Zuber, who is also my academic advisor for my Film Studies major. I hope to undertake this screenwriting independent study for a variety of reasons. First of all, there is not currently a screenwriting course being offered this semester. Given the nature of the film project I am hoping to produce, it is crucial that I begin the screenwriting process this semester, so that I can then have a complete idea of what my film is going to entail so that I can undertake pre-production planning efforts in the Spring semester, and be ready to start production during the Summer of 2010. -

Interracial Bw/Wm Romance Movies.Docx

Black Women, White Men: Interracial Romance in the Movies list of theatrical and made-for-TV movies that feature romantic relationships between black women and white men. Prior to the 1960s, it was very common for light- skinned black characters to be portrayed by white actors TITLE YEAR WOMAN MAN 200 Cigarettes 1999 Nicole Ari Parker Ben Affleck 24 Hours in London 2000 Anjela Lauren Smith Gary Olsen 25th Hour 2002 Rosario Dawson Edward Norton 28 Days Later … 2002 Naomie Harris Cillian Murphy 3-Way 2004 Joy Bryant Dominic Purcell Action Jackson 1988 Vanity Craig T. Nelson Ace Ventura: When 1995 Sophie Okonedo Jim Carrey Nature Calls A Diva’s Christmas 2000 Vanessa Williams Brian McNamara Carol After the Sunset 2004 Naomie Harris Woody Harrelson Alfie 2004 Nia Long Jude Law All Night Long 1961 Marti Stevens Paul Harris Alexander 2004 Rosario Dawson Colin Farrell American Flyers 1985 Rae Dawn Chong Kevin Costner America’s Dream 1996 Tina Lifford Tate Donovan Angel Heart 1987 Lisa Bonet Mickey Rourke Annie 1999 Audra McDonald Victor Garber Antibody 2002 Robin Givens Lance Henriksen A Perfect Fit 2005 Leila Arcieri Adrian Grenier Ash Wednesday 2002 Rosario Dawson Elijah Wood Ashanti 1979 Beverly Johnson Michael Caine August 2008 Naomie Harris Josh Hartnett Austin Powers in 2002 Beyonce Knowles Mike Meyers Goldmember Bachelor, the 1999 Mariah Carey Chris O’Donnell Bamboozled 2000 na Michael Rapaport Band of Angels 1957 Yvonne De Carlo Clark Gable Barbershop 2002 ? Troy Garrity Besieged 1998 Thandie Newton David Thewlis Better Dayz 2002 Shantell -

01N Cover WETA Feb16.Indd

FEBRUARY 2016 MAGAZINE FOR MEMBERS Smithsonian Salutes Ray Charles: In Performance at the White House WETA production airs February 26 PBS NewsHour will produce the Democratic Primary Debate in Milwaukee, February 11 at 9 p.m. Washington Week with Gwen Ifi ll presents a Special Edition from Milwaukee, February 12 at 8 p.m. WETA Focus With the first of the 2016 political primaries taking place this month, the election season officially begins, and the WETA news and public affairs productions PBS NewsHour and Washington Week with Gwen Ifill, which form the core of PBS Election 2016 coverage, will help Americans learn about the choices before them. This month, PBS NewsHour and Washington Week present very special programs. On February 11 in Milwaukee, PBS NewsHour will produce a Democratic Primary Debate, to be broadcast live with NewsHour anchors and managing editors Gwen Ifill and Judy Woodruff serving as moderators. It is fitting that two of America’s finest journalists will guide this candidates debate. In service to the public, Gwen and Judy will bring to bear the trademark intelligence, balance and gravitas of one of the nation’s most trusted and respected news operations as they elicit candidates’ views on issues facing the nation. Washington Week with Gwen Ifill also heads to Milwaukee, to present two special February 12 broad- casts taped before a live audience, as Gwen and the program’s panel of eminent journalists analyze the debate and other news of the week. Their intriguing, thoughtful conversations always yield fascinating insights. We at WETA are enormously proud of the superb, vital journalism of PBS NewsHour and Washington Week, which elevates the national political dialogue. -

Caught Between Presence and Absence: Shakespeare's Tragic Women on Film

Caught between presence and absence: Shakespeare's tragic women on film Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Scott, Lindsey A. Publisher University of Liverpool (University of Chester) Rights screenshots reproduced under s.30 (1) of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. Further re-use (except as permitted by law) is not allowed. Download date 04/10/2021 11:49:26 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/100153 This work has been submitted to ChesterRep – the University of Chester’s online research repository http://chesterrep.openrepository.com Author(s): Lindsey A Scott Title: Caught between presence and absence: Shakespeare's tragic women on film Date: October 2008 Originally published as: University of Liverpool PhD thesis Example citation: Scott, Lindsey A. (2008). Caught between presence and absence: Shakespeare's tragic women on film. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Liverpool, United Kingdom. Version of item: Submitted version Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10034/100153 Caught Between Presence and Absence: Shakespeare’s Tragic Women on Film Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy By Lindsey A. Scott October 2008 Declaration I declare that the material presented in this thesis is all my own work and has not been submitted for another award of the University of Liverpool or any other Higher Education Institution. Signed Lindsey A Scott Dated 27/08/09 Usually a physical presence – moving in space or making its own distinctive sounds – the body may also manifest itself only in verbal traces, or in echoes which signify its absence. -

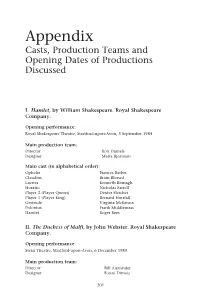

Appendix Casts, Production Teams and Opening Dates of Productions Discussed

Appendix Casts, Production Teams and Opening Dates of Productions Discussed I. Hamlet, by William Shakespeare. Royal Shakespeare Company. Opening performance: Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, 5 September 1984 Main production team: Director Ron Daniels Designer Maria Bjornson Main cast (in alphabetical order): Ophelia Frances Barber Claudius Brian Blessed Laertes Kenneth Branagh Horatio Nicholas Farrell Player 2 (Player Queen) Dexter Fletcher Player 1 (Player King) Bernard Horsfall Gertrude Virginia McKenna Polonius Frank Middlemass Hamlet Roger Rees II. The Duchess of Malfi, by John Webster. Royal Shakespeare Company. Opening performance: Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, 6 December 1989 Main production team: Director Bill Alexander Designer Fotini Dimou 201 202 Appendix Main cast (in alphabetical order): Duke Ferdinand Bruce Alexander The Cardinal Russell Dixon Cariola Sally Edwards Antonio Bologna Mick Ford Julia Patricia Kerrigan Daniel de Bosola Nigel Terry The Duchess of Malfi Harriet Walter III. The Duchess of Malfi, by John Webster. Cheek By Jowl. Opening performances: Bury St. Edmunds, 19 September 1995 Wyndham’s Theatre, London, 2 January 1996 Main production team: Director Declan Donnellan Designer Nick Ormerod Main cast (in alphabetical order): Daniel de Bosola George Anton The Cardinal Paul Brennen Cariola Avril Clark Duke Ferdinand Scott Handy The Duchess of Malfi Anastasia Hille Antonio Bologna Matthew Macfadyen Julia Nicola Redmond IV. Titus, based on Titus Andronicus, by William Shakespeare. Motion Picture.