Lecture 29. Bernouilli Brothers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leibniz's Differential Calculus Applied to the Catenary

Leibniz’s differential calculus applied to the catenary Olivier Keller, agrégé in mathematics, PhD (EHESS) Study of the catenary was a response to a challenge laid down by Jacques Bernoulli, and which was successfully met by Leibniz as well as by Jean Bernoulli and Huygens: to find the curve described by a piece of strung suspended from its two ends. Stimulated by the success of this initial research, Jean Bernoulli put forward and solved similar problems: the form taken by a horizontal blade immobilised on one side, with a weight attached to the other; the form taken by a piece of linen filled with liqueur; the curve of a sail. Challenges among scholars In the 17th century, it was customary for scholars to set each other challenges in alternate issues of journals. Leibniz, for example, challenged the Cartesians – as part of the controversy surrounding the laws of collision, known as the “querelle des forces vives” (vis viva controversy) – to find the curve down which a body falls at constant vertical velocity (isochrone curve). Put forward in the Nouvelle République des Lettres of September 1687, this problem received Huygens’ solution in October of the same year, while Leibniz’s appeared in 1689 in the journal he had created, the Acta Eruditorum. Another famous example is that of the brachistochrone, or the “curve of the fastest descent”, which, thanks to the new differential calculus, proved to be not a circle, as Galileo had believed, but a cycloid: the challenge had been set by Jean Bernoulli in the Acta Eruditorum in June 1696, and was resolved by Leibniz in May 1697. -

Brief History of the Early Development of Theoretical and Experimental Fluid Dynamics

Brief History of the Early Development of Theoretical and Experimental Fluid Dynamics John D. Anderson Jr. Aeronautics Division, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA 1 INTRODUCTION 1 Introduction 1 2 Early Greek Science: Aristotle and Archimedes 2 As you read these words, there are millions of modern engi- neering devices in operation that depend in part, or in total, 3 DA Vinci’s Fluid Dynamics 2 on the understanding of fluid dynamics – airplanes in flight, 4 The Velocity-Squared Law 3 ships at sea, automobiles on the road, mechanical biomedi- 5 Newton and the Sine-Squared Law 5 cal devices, and so on. In the modern world, we sometimes take these devices for granted. However, it is important to 6 Daniel Bernoulli and the Pressure-Velocity pause for a moment and realize that each of these machines Concept 7 is a miracle in modern engineering fluid dynamics wherein 7 Henri Pitot and the Invention of the Pitot Tube 9 many diverse fundamental laws of nature are harnessed and 8 The High Noon of Eighteenth Century Fluid combined in a useful fashion so as to produce a safe, efficient, Dynamics – Leonhard Euler and the Governing and effective machine. Indeed, the sight of an airplane flying Equations of Inviscid Fluid Motion 10 overhead typifies the laws of aerodynamics in action, and it 9 Inclusion of Friction in Theoretical Fluid is easy to forget that just two centuries ago, these laws were Dynamics: the Works of Navier and Stokes 11 so mysterious, unknown or misunderstood as to preclude a flying machine from even lifting off the ground; let alone 10 Osborne Reynolds: Understanding Turbulent successfully flying through the air. -

The Bernoulli Edition the Collected Scientific Papers of the Mathematicians and Physicists of the Bernoulli Family

Bernoulli2005.qxd 24.01.2006 16:34 Seite 1 The Bernoulli Edition The Collected Scientific Papers of the Mathematicians and Physicists of the Bernoulli Family Edited on behalf of the Naturforschende Gesellschaft in Basel and the Otto Spiess-Stiftung, with support of the Schweizerischer Nationalfonds and the Verein zur Förderung der Bernoulli-Edition Bernoulli2005.qxd 24.01.2006 16:34 Seite 2 The Scientific Legacy Èthe Bernoullis' contributions to the theory of oscillations, especially Daniel's discovery of of the Bernoullis the main theorems on stationary modes. Johann II considered, but rejected, a theory of Modern science is predominantly based on the transversal wave optics; Jacob II came discoveries in the fields of mathematics and the tantalizingly close to formulating the natural sciences in the 17th and 18th centuries. equations for the vibrating plate – an Eight members of the Bernoulli family as well as important topic of the time the Bernoulli disciple Jacob Hermann made Èthe important steps Daniel Bernoulli took significant contributions to this development in toward a theory of errors. His efforts to the areas of mathematics, physics, engineering improve the apparatus for measuring the and medicine. Some of their most influential inclination of the Earth's magnetic field led achievements may be listed as follows: him to the first systematic evaluation of ÈJacob Bernoulli's pioneering work in proba- experimental errors bility theory, which included the discovery of ÈDaniel's achievements in medicine, including the Law of Large Numbers, the basic theorem the first computation of the work done by the underlying all statistical analysis human heart. -

The Bernoulli Family

Mathematical Discoveries of the Bernoulli Brothers Caroline Ellis Union University MAT 498 November 30, 2001 Bernoulli Family Tree Nikolaus (1623-1708) Jakob I Nikolaus I Johann I (1654-1705) (1662-1716) (1667-1748) Nikolaus II Nikolaus III Daniel I Johann II (1687-1759) (1695-1726) (1700-1782) (1710-1790) This Swiss family produced eight mathematicians in three generations. We will focus on some of the mathematical discoveries of Jakob l and his brother Johann l. Some History Nikolaus Bernoulli wanted Jakob to be a Protestant pastor and Johann to be a doctor. They obeyed their father and earned degrees in theology and medicine, respectively. But… Some History, cont. Jakob and Johann taught themselves the “new math” – calculus – from Leibniz‟s notes and papers. They started to have contact with Leibniz, and are now known as his most important students. http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/history/PictDisplay/Leibniz.html Jakob Bernoulli (1654-1705) learned about mathematics and astronomy studied Descarte‟s La Géometrie, John Wallis‟s Arithmetica Infinitorum, and Isaac Barrow‟s Lectiones Geometricae convinced Leibniz to change the name of the new math from calculus sunmatorius to calculus integralis http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/history/PictDisplay/Bernoulli_Jakob.html Johann Bernoulli (1667-1748) studied mathematics and physics gave calculus lessons to Marquis de L‟Hôpital Johann‟s greatest student was Euler won the Paris Academy‟s biennial prize competition three times – 1727, 1730, and 1734 http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/history/PictDisplay/Bernoulli_Johann.html Jakob vs. Johann Johann Bernoulli had greater intuitive power and descriptive ability Jakob had a deeper intellect but took longer to arrive at a solution Famous Problems the catenary (hanging chain) the brachistocrone (shortest time) the divergence of the harmonic series (1/n) The Catenary: Hanging Chain Jakob Bernoulli Galileo guessed that proposed this problem this curve was a in the May 1690 edition parabola, but he never of Acta Eruditorum. -

Introduction to the Modern Calculus of Variations

MA4G6 Lecture Notes Introduction to the Modern Calculus of Variations Filip Rindler Spring Term 2015 Filip Rindler Mathematics Institute University of Warwick Coventry CV4 7AL United Kingdom [email protected] http://www.warwick.ac.uk/filiprindler Copyright ©2015 Filip Rindler. Version 1.1. Preface These lecture notes, written for the MA4G6 Calculus of Variations course at the University of Warwick, intend to give a modern introduction to the Calculus of Variations. I have tried to cover different aspects of the field and to explain how they fit into the “big picture”. This is not an encyclopedic work; many important results are omitted and sometimes I only present a special case of a more general theorem. I have, however, tried to strike a balance between a pure introduction and a text that can be used for later revision of forgotten material. The presentation is based around a few principles: • The presentation is quite “modern” in that I use several techniques which are perhaps not usually found in an introductory text or that have only recently been developed. • For most results, I try to use “reasonable” assumptions, not necessarily minimal ones. • When presented with a choice of how to prove a result, I have usually preferred the (in my opinion) most conceptually clear approach over more “elementary” ones. For example, I use Young measures in many instances, even though this comes at the expense of a higher initial burden of abstract theory. • Wherever possible, I first present an abstract result for general functionals defined on Banach spaces to illustrate the general structure of a certain result. -

ON the BRACHISTOCHRONE PROBLEM 1. Introduction. The

ON THE BRACHISTOCHRONE PROBLEM OLEG ZUBELEVICH STEKLOV MATHEMATICAL INSTITUTE OF RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES DEPT. OF THEORETICAL MECHANICS, MECHANICS AND MATHEMATICS FACULTY, M. V. LOMONOSOV MOSCOW STATE UNIVERSITY RUSSIA, 119899, MOSCOW, MGU [email protected] Abstract. In this article we consider different generalizations of the Brachistochrone Problem in the context of fundamental con- cepts of classical mechanics. The correct statement for the Brachis- tochrone problem for nonholonomic systems is proposed. It is shown that the Brachistochrone problem is closely related to vako- nomic mechanics. 1. Introduction. The Statement of the Problem The article is organized as follows. Section 3 is independent on other text and contains an auxiliary ma- terial with precise definitions and proofs. This section can be dropped by a reader versed in the Calculus of Variations. Other part of the text is less formal and based on Section 3. The Brachistochrone Problem is one of the classical variational prob- lems that we inherited form the past centuries. This problem was stated by Johann Bernoulli in 1696 and solved almost simultaneously by him and by Christiaan Huygens and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Since that time the problem was discussed in different aspects nu- merous times. We do not even try to concern this long and celebrated history. 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification. 70G75, 70F25,70F20 , 70H30 ,70H03. Key words and phrases. Brachistochrone, vakonomic mechanics, holonomic sys- tems, nonholonomic systems, Hamilton principle. The research was funded by a grant from the Russian Science Foundation (Project No. 19-71-30012). 1 2 OLEG ZUBELEVICH This article is devoted to comprehension of the Brachistochrone Problem in terms of the modern Lagrangian formalism and to the gen- eralizations which such a comprehension involves. -

Leonhard Euler: His Life, the Man, and His Works∗

SIAM REVIEW c 2008 Walter Gautschi Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 3–33 Leonhard Euler: His Life, the Man, and His Works∗ Walter Gautschi† Abstract. On the occasion of the 300th anniversary (on April 15, 2007) of Euler’s birth, an attempt is made to bring Euler’s genius to the attention of a broad segment of the educated public. The three stations of his life—Basel, St. Petersburg, andBerlin—are sketchedandthe principal works identified in more or less chronological order. To convey a flavor of his work andits impact on modernscience, a few of Euler’s memorable contributions are selected anddiscussedinmore detail. Remarks on Euler’s personality, intellect, andcraftsmanship roundout the presentation. Key words. LeonhardEuler, sketch of Euler’s life, works, andpersonality AMS subject classification. 01A50 DOI. 10.1137/070702710 Seh ich die Werke der Meister an, So sehe ich, was sie getan; Betracht ich meine Siebensachen, Seh ich, was ich h¨att sollen machen. –Goethe, Weimar 1814/1815 1. Introduction. It is a virtually impossible task to do justice, in a short span of time and space, to the great genius of Leonhard Euler. All we can do, in this lecture, is to bring across some glimpses of Euler’s incredibly voluminous and diverse work, which today fills 74 massive volumes of the Opera omnia (with two more to come). Nine additional volumes of correspondence are planned and have already appeared in part, and about seven volumes of notebooks and diaries still await editing! We begin in section 2 with a brief outline of Euler’s life, going through the three stations of his life: Basel, St. -

The Bernoullis and the Harmonic Series

The Bernoullis and The Harmonic Series By Candice Cprek, Jamie Unseld, and Stephanie Wendschlag An Exciting Time in Math l The late 1600s and early 1700s was an exciting time period for mathematics. l The subject flourished during this period. l Math challenges were held among philosophers. l The fundamentals of Calculus were created. l Several geniuses made their mark on mathematics. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) l Described as a universal l At age 15 he entered genius by mastering several the University of different areas of study. Leipzig, flying through l A child prodigy who studied under his father, a professor his studies at such a of moral philosophy. pace that he completed l Taught himself Latin and his doctoral dissertation Greek at a young age, while at Altdorf by 20. studying the array of books on his father’s shelves. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz l He then began work for the Elector of Mainz, a small state when Germany divided, where he handled legal maters. l In his spare time he designed a calculating machine that would multiply by repeated, rapid additions and divide by rapid subtractions. l 1672-sent form Germany to Paris as a high level diplomat. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz l At this time his math training was limited to classical training and he needed a crash course in the current trends and directions it was taking to again master another area. l When in Paris he met the Dutch scientist named Christiaan Huygens. Christiaan Huygens l He had done extensive work on mathematical curves such as the “cycloid”. -

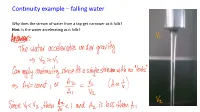

Continuity Example – Falling Water

Continuity example – falling water Why does the stream of water from a tap get narrower as it falls? Hint: Is the water accelerating as it falls? Answer: The fluid accelerates under gravity so the velocity is higher down lower. Since Av = const (i.e. A is inversely proportional to v), the cross sectional area, and the radius, is smaller down lower Bernoulli’s principle Bernoulli conducted experiments like this: https://youtu.be/9DYyGYSUhIc (from 2:06) A fluid accelerates when entering a narrow section of tube, increasing its kinetic energy (=½mv2) Something must be doing work on the parcel. But what? Bernoulli’s principle resolves this dilemma. Daniel Bernoulli “An increase in the speed of an ideal fluid is accompanied 1700-1782 by a drop in its pressure.” The fluid is pushed from behind Examples of Bernoulli’s principle Aeroplane wings high v, low P Compressible fluids? Bernoulli’s equation OK if not too much compression. Venturi meters Measure velocity from pressure difference between two points of known cross section. Bernoulli’s equation New Concept: A fluid parcel of volume V at pressure P has a pressure potential energy Epot-p = PV. It also has gravitational potential energy: Epot-g = mgh Ignoring friction, the energy of the parcel as it flows must be constant: Ek + Epot = const 1 mv 2 + PV + mgh = const ) 2 For incompressible fluids, we can divide by volume, showing conservation of energy 1 density: ⇢v 2 + P + ⇢gh = const 2 This is Bernoulli’s equation. Bernoulli equation example – leak in water tank A full water tank 2m tall has a hole 5mm diameter near the base. -

Leonhard Euler - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 14

Leonhard Euler - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 14 Leonhard Euler From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Leonhard Euler ( German pronunciation: [l]; English Leonhard Euler approximation, "Oiler" [1] 15 April 1707 – 18 September 1783) was a pioneering Swiss mathematician and physicist. He made important discoveries in fields as diverse as infinitesimal calculus and graph theory. He also introduced much of the modern mathematical terminology and notation, particularly for mathematical analysis, such as the notion of a mathematical function.[2] He is also renowned for his work in mechanics, fluid dynamics, optics, and astronomy. Euler spent most of his adult life in St. Petersburg, Russia, and in Berlin, Prussia. He is considered to be the preeminent mathematician of the 18th century, and one of the greatest of all time. He is also one of the most prolific mathematicians ever; his collected works fill 60–80 quarto volumes. [3] A statement attributed to Pierre-Simon Laplace expresses Euler's influence on mathematics: "Read Euler, read Euler, he is our teacher in all things," which has also been translated as "Read Portrait by Emanuel Handmann 1756(?) Euler, read Euler, he is the master of us all." [4] Born 15 April 1707 Euler was featured on the sixth series of the Swiss 10- Basel, Switzerland franc banknote and on numerous Swiss, German, and Died Russian postage stamps. The asteroid 2002 Euler was 18 September 1783 (aged 76) named in his honor. He is also commemorated by the [OS: 7 September 1783] Lutheran Church on their Calendar of Saints on 24 St. Petersburg, Russia May – he was a devout Christian (and believer in Residence Prussia, Russia biblical inerrancy) who wrote apologetics and argued Switzerland [5] forcefully against the prominent atheists of his time. -

UTOPIAE Optimisation and Uncertainty Quantification CPD for Teachers of Advanced Higher Physics and Mathematics

UTOPIAE Optimisation and Uncertainty Quantification CPD for Teachers of Advanced Higher Physics and Mathematics Outreach Material Peter McGinty Annalisa Riccardi UTOPIAE, UNIVERSITY OF STRATHCLYDE GLASGOW - UK This research was funded by the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 programme under grant number 722734 First release, October 2018 Contents 1 Introduction ....................................................5 1.1 Who is this for?5 1.2 What are Optimisation and Uncertainty Quantification and why are they im- portant?5 2 Optimisation ...................................................7 2.1 Brachistochrone problem definition7 2.2 How to solve the problem mathematically8 2.3 How to solve the problem experimentally 10 2.4 Examples of Brachistochrone in real life 11 3 Uncertainty Quantification ..................................... 13 3.1 Probability and Statistics 13 3.2 Experiment 14 3.3 Introduction of Uncertainty 16 1. Introduction 1.1 Who is this for? The UTOPIAE Network is committed to creating high quality engagement opportunities for the Early Stage Researchers working within the network and also outreach materials for the wider academic community to benefit from. Optimisation and Uncertainty Quantification, whilst representing the future for a large number of research fields, are relatively unknown disciplines and yet the benefit and impact they can provide for researchers is vast. In order to try to raise awareness, UTOPIAE has created a Continuous Professional Development online resource and training sessions aimed at teachers of Advanced Higher Physics and Mathematics, which is in line with Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence. Sup- ported by the Glasgow City Council, the STEM Network, and Scottish Schools Education Resource Centre these materials have been published online for teachers to use within a classroom context. -

A Tale of the Cycloid in Four Acts

A Tale of the Cycloid In Four Acts Carlo Margio Figure 1: A point on a wheel tracing a cycloid, from a work by Pascal in 16589. Introduction In the words of Mersenne, a cycloid is “the curve traced in space by a point on a carriage wheel as it revolves, moving forward on the street surface.” 1 This deceptively simple curve has a large number of remarkable and unique properties from an integral ratio of its length to the radius of the generating circle, and an integral ratio of its enclosed area to the area of the generating circle, as can be proven using geometry or basic calculus, to the advanced and unique tautochrone and brachistochrone properties, that are best shown using the calculus of variations. Thrown in to this assortment, a cycloid is the only curve that is its own involute. Study of the cycloid can reinforce the curriculum concepts of curve parameterisation, length of a curve, and the area under a parametric curve. Being mechanically generated, the cycloid also lends itself to practical demonstrations that help visualise these abstract concepts. The history of the curve is as enthralling as the mathematics, and involves many of the great European mathematicians of the seventeenth century (See Appendix I “Mathematicians and Timeline”). Introducing the cycloid through the persons involved in its discovery, and the struggles they underwent to get credit for their insights, not only gives sequence and order to the cycloid’s properties and shows which properties required advances in mathematics, but it also gives a human face to the mathematicians involved and makes them seem less remote, despite their, at times, seemingly superhuman discoveries.