The 10-Tenets of Adaptive Management and Sustainability: an Holistic Framework for Understanding and Managing the Socio-Ecological System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ensuring Availability and Sustainable Management Of

Issue brief SDG 6 © Dan-Roizer ENSURING AVAILABILITY AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF WATER AND SANITATION FOR ALL Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6) – Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all – confirms the importance of water and sanitation in the global political agenda. Building on the relevant Millennium Development Goal, SDG 6 addresses the sustainability of access to water and sanitation by focusing on the quality, availability and management of freshwater resources. The individual targets of SDG 6 Environmental dimension of UN Environment and SDG 6 cover the entire water cycle and its SDG 6 interconnections: As the global environmental authority, the SDG 6 recognizes that countries’ social United Nations Environment Programme ➡ 6.1: provision of drinking water development and economic prosperity (UN Environment) connects the issue of depend on the sustainable management of freshwater to other aspects of sustainable ➡ 6.2: sanitation and hygiene freshwater resources and ecosystems. development, such as oceans, land and services SDG 6 acknowledges that ecosystems and agriculture. This work entails building their inhabitants, including humans, are national capacity to monitor freshwater ➡ 6.3: treatment and reuse of water users and that their activities on land ecosystem health, including water wastewater and ambient can compromise the quality and availability quality, facilitating integrated water water quality of fresh water. resources management processes and ➡ 6.4: water-use efficiency and the implementation thereof, and providing scarcity The water-related ecosystems addressed guidelines and inputs for country-level in SDG 6 include wetlands, rivers, aquifers action to protect and restore freshwater ➡ 6.5: integrated water resources and lakes, which sustain a high level of ecosystems at the national level. -

Ecological Sustainability Within California's Improved Forest Management Carbon Offsets Program Cory Hertog Clark University, [email protected]

Clark University Clark Digital Commons International Development, Community and Master’s Papers Environment (IDCE) 5-2018 Ecological Sustainability within California's Improved Forest Management Carbon Offsets Program Cory Hertog Clark University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers Part of the Environmental Policy Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Physical and Environmental Geography Commons, and the Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons Recommended Citation Hertog, Cory, "Ecological Sustainability within California's Improved Forest Management Carbon Offsets Program" (2018). International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE). 195. https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers/195 This Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Master’s Papers at Clark Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE) by an authorized administrator of Clark Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Ecological Sustainability within California’s Improved Forest Management Carbon Offsets Program Cory Hertog May 2018 A Master’s Paper Submitted to the faculty of Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Science of Environmental Science and Policy in the department of International Development, Community, and Environment and a Master of Business Administration in the Graduate School of Management And accepted on the recommendation of Dominik Kulakowski - Ph.D. Will O’Brien - J.D., M.B.A Graduate School of Geography Graduate School of Management Abstract Ecological Sustainability within California’s Improved Forest Management Carbon Offsets Program Cory Hertog Forest Carbon offsets are being used as a climate change mitigation strategy in multiple programs around the world. -

Sustainable Livelihoods and Ecosystems Management

Created in 1948, IUCN - The World Conservation Union brings together 77 states, 112 government agencies, 735 NGOs, 35 affiliates, and some 10,000 scientists and experts from 181 countries in a unique worldwide partnership. IUCN’s mission is to influence, e ncourage and assist societies throughout the world to con- serve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustain- able. IUCN is the world's largest environmental knowledge network and has helped over 75 countries to prepare and implement national conservation and biodiversity strategies. IUCN is a multi- cultural, multilingual organization with 1000 staff located in 42 countries. Its headquarters are in Gland, Switzerland. http://www.iucn.org [email protected] Sustainable livelihoods and ecosystems management For the Preparatory Committee for the World Summit on Sustainable Development - 4 th Preparatory Meeting, Bali (Indonesia) While one cannot say with any confidence what forms an ecological crunch might take, when it might happen, or how severe it might be, it is easier to predict who will have the worst of it. The poor and powerless cannot shield themselves from ecological problems today, nor will they be able to do it in the future. J.R. McNeill, “Something New under the Sun” Introduction As a conservation organization that puts people at centre stage in its mission and vision, IUCN welcomes the new international focus on poverty alleviation. We know from our own experience that the pursuit of enviro nmental goals at the expense of economic well-being and social justice is doomed to fail. -

Green Consumerism: Moral Motivations to a Sustainable Future

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Green consumerism: moral motivations to a sustainable future 1 2 3 Sonya Sachdeva , Jennifer Jordan and Nina Mazar Green consumerism embodies a dilemma inherent in many more expensive green products that may act as a barrier to prosocial and moral actions — foregoing personal gain in favor engaging in green consumerism. Nonetheless there are of a more abstract, somewhat intangible gain to someone or several recurring themes in the expanse of literature on something else. In addition, as in the case of purchasing more the topic of green consumerism, which may shine a light expensive green products, there is sometimes a very literal cost on ways to promote green consumerism. that may act as a barrier to engaging in green consumerism. The current review examines endogenous, exogenous, and structural factors that promote green consumerism. We also What is green consumerism? 4 discuss its potential positive and negative spillover effects. We Oxymoronic implications aside, green consumerism is, close by discussing areas of research on green consumerism for a significant portion of the Western industrial popula- that are lacking — such as the moral framing of green tion, an accessible way to engage in pro-environmental, consumerism and the expansion of the cultural context in which sustainable behavior. An operational definition of green it is defined and studied. consumerism subsumes a list of behaviors that are under- Addresses taken with the intention of promoting positive environ- 1 5 U.S. Forest Service, United States mental effects. Some prototypical behaviors that fall 2 University of Groningen, The Netherlands within this rather vague definition are purchasing appli- 3 University of Toronto, Canada ances with energy star labels, buying organic products, or turning off electrical appliances when not in use, and Corresponding author: Sachdeva, Sonya ([email protected]) taking shorter showers. -

Perspectives on Climate Change and Sustainability

20 Perspectives on climate change and sustainability Coordinating Lead Authors: Gary W. Yohe (USA), Rodel D. Lasco (Philippines) Lead Authors: Qazi K. Ahmad (Bangladesh), Nigel Arnell (UK), Stewart J. Cohen (Canada), Chris Hope (UK), Anthony C. Janetos (USA), Rosa T. Perez (Philippines) Contributing Authors: Antoinette Brenkert (USA), Virginia Burkett (USA), Kristie L. Ebi (USA), Elizabeth L. Malone (USA), Bettina Menne (WHO Regional Office for Europe/Germany), Anthony Nyong (Nigeria), Ferenc L. Toth (Hungary), Gianna M. Palmer (USA) Review Editors: Robert Kates (USA), Mohamed Salih (Sudan), John Stone (Canada) This chapter should be cited as: Yohe, G.W., R.D. Lasco, Q.K. Ahmad, N.W. Arnell, S.J. Cohen, C. Hope, A.C. Janetos and R.T. Perez, 2007: Perspectives on climate change and sustainability. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 811-841. Perspectives on climate change and sustainable development Chapter 20 Table of Contents .....................................................813 Executive summary 20.7 Implications for regional, sub-regional, local and sectoral development; access ...................814 .............826 20.1 Introduction: setting the context to resources and technology; equity 20.7.1 Millennium Development Goals – 20.2 A synthesis of new knowledge relating -

A Critical Reading of Permaculture Literature

Master thesis in Sustainable Development 2018/14 Examensarbete i Hållbar utveckling The quest for sustainability – a critical reading of permaculture literature ‘ Tove Janzon DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES INSTITUTIONEN FÖR GEOVETENSKAPER Master thesis in Sustainable Development 2018/14 Examensarbete i Hållbar utveckling The quest for sustainability – a critical reading of permaculture literature Tove Janzon Supervisor: Frans Lenglet Evaluator: Petra Hansson Copyright © Tove Janzon and the Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University Published at Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University (www.geo.uu.se), Uppsala, 2018 Content 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Background ........................................................................................................................................ 1 2.1 The sustainable development concept ........................................................................................... 1 2.1.1 History .................................................................................................................................... 1 2.1.2 Definitions .............................................................................................................................. 2 2.2 The permaculture concept ............................................................................................................. 2 2.2.1 History ................................................................................................................................... -

Inclusion of Life Cycle Thinking in a Sustainability-Oriented Consumer's

sustainability Article Inclusion of Life Cycle Thinking in a Sustainability-Oriented Consumer’s Typology: A Proposed Methodology and an Assessment Tool Anna Lewandowska 1,*, Joanna Witczak 1, Pasquale Giungato 2 ID , Christian Dierks 3, Przemyslaw Kurczewski 4 and Katarzyna Pawlak-Lemanska 1 1 Faculty of Commodity Science, Poznan University of Economics and Business, 61-875 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] (J.W.); [email protected] (K.P.-L.) 2 Chemistry Department, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Taranto district-via Alcide de Gasperi, 74123 Taranto, Italy; [email protected] 3 Fraunhofer Project Group Materials Recycling and Resource Strategies, Brentanostrasse 2a, 63755 Alzenau, Germany; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Machines and Transportation, Poznan University of Technology, Piotrowo 3, 60-965 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-61-854-3121 Received: 8 April 2018; Accepted: 29 May 2018; Published: 1 June 2018 Abstract: Characterizing consumers in terms of their propensity to practice sustainable consumption represents an interesting research challenge in which a crucial role is played by the questionnaire in terms of its structure and classification criteria. Various classification rules have been proposed in the literature, which can be used to identify consumer types and signify their propensity to practice the principles of sustainable development in daily life. In this paper, we based our approach in designing a classification tool on a combination of two elements: the concept of voluntary simplicity as a pillar for consumer characteristics and the idea of assessing consumers by using filters, in a modified form introducing many new aspects of life-cycle thinking. -

Sustainable Water Management and Wetland Restoration Strategies in Northern China

China Sustainable Water This book depicts the results of a research project in northern China, where an international and interdisciplinary team of researchers from Italy, Germany and China has applied a broad range of methodology in order to answer basic and Management applied research questions and derive comprehensive re- commendations for sustainable water management and wetland restoration. The project primarily focused on eco- system services, e.g. the purification of water and biomass and Wetland production. In particular, the ecosystem function and use of reed (Phragmites australis) and the perception as well as the value of water as a resource for Central Asia’s multicultural societies was analysed. Restoration Strategies in Northern China Sustainable Water Management and Wetland Restoration Strategies in Northern in Strategies Restoration Wetland and Management Water Sustainable Edited by Giuseppe Tommaso Cirella Stefan Zerbe Cirella, Zerbe (eds.) (eds.) Zerbe Cirella, 25,00 Euro www.unibz.it/universitypress Sustainable Water Management and Wetland Restoration Strategies in Northern China Edited by Giuseppe Tommaso Cirella Stefan Zerbe On behalf of Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft Kurt-Eberhard-Bode-Stiftung für medizinische und naturwissenschaftliche Forschung Design: DOC.bz Printing: Digiprint, Bozen/Bolzano © 2014 by Bozen-Bolzano University Press Free University of Bozen-Bolzano All rights reserved 1st edition www.unibz.it/universitypress ISBN 978-88-6046-069-1 E-ISBN 978-88-6046-109-4 This work—excluding the cover and the quotations—is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Contents Introduction Stefan Zerbe, Giuseppe Tommaso Cirella, Niels Thevs ............................................. 1 1. SuWaRest, the “Third Culture” and environmental ethics Konrad Ott ............................................................................................................ -

Synergies Between Adaptation and Mitigation

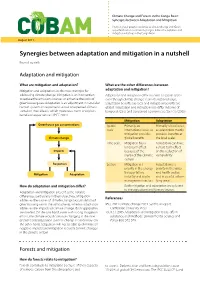

Climate Change and Forests in the Congo Basin: Synergies between Adaptation and Mitigation Analysing local people’s resilience to climate change and REDD+ opportunities to recommend synergies between adaptation and mitigation initiatives in the Congo Basin August 2011 Synergies between adaptation and mitigation in a nutshell Bruno Locatelli Adaptation and mitigation What are mitigation and adaptation? What are the other differences between Mitigation and adaptation are the two strategies for adaptation and mitigation? addressing climate change. Mitigation is an intervention Adaptation and mitigation differ in terms of spatial scales: to reduce the emissions sources or enhance the sinks of even though climate change is an international issue, greenhouse gases. Adaptation is an ‘adjustment in natural or adaptation benefits are local and mitigation benefits are human systems in response to actual or expected climatic global. Adaptation and mitigation also differ in terms of stimuli or their effects, which moderates harm or exploits temporal scales and concerned economic sectors (Tol 2005). beneficial opportunities’ (IPCC 2001). Mitigation Adaptation Greenhouse gas concentrations Spatial Primarily an Primarily a local issue, scale international issue, as as adaptation mostly mitigation provides provides benefits at Climate change global benefits the local scale Time scale Mitigation has a Adaptation can have long-term effect a short-term effect Impacts because of the on the reduction of inertia of the climatic vulnerability system Responses Sectors Mitigation is a Adaptation is a priority in the energy, priority in the water transportation, and health sectors Mitigation Adaptation industry and waste and in coastal or low- management sectors lying areas How do adaptation and mitigation differ? Both mitigation and adaptation are relevant to the agriculture and forestry sectors Adaptation and mitigation present some notable differences, particularly in their objectives. -

MAB) Programme and Its World Network of Biosphere Reserves MAB Strategy (2015-2025) Lima Action Plan (2016-2025) Lima Declaration

United Nations Man and Educational, Scientific and the Biosphere Cultural Organization Programme A New Roadmap for the Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme and its World Network of Biosphere Reserves MAB Strategy (2015-2025) Lima Action Plan (2016-2025) Lima Declaration Man and the Biosphere Programme UNESCO 7, place de Fontenoy F-75352 Paris 07 SP France E-mail: [email protected] 9 789231 002069 A New Roadmap for the Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme and its World Network of Biosphere Reserves MAB Strategy (2015-2025) Lima Action Plan (2016-2025) Lima Declaration Published in 2017 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France © UNESCO 2017 ISBN 978-92-3-100206-9 This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. -

Forest Carbon Trading and Marketing in the United States1

Forest Carbon Trading and Marketing in the United States1 Steven Ruddell2 Michael J. Walsh, PhD Murali Kanakasabai, PhD October 2006 1. Introduction During the 1992 Earth Summit convened by the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, a rudimentary framework for a global emission trading system was presented in a “side show” in a tent. Concern over climate change was limited to a few scientists and environmentalists and the idea was received with great skepticism. The concept of emissions trading was but a theoretical chapter in economics textbooks. Fourteen years later, the situation is quite different. Market-based mechanisms such as emissions trading have become widely accepted as a cost-effective method for addressing climate change and other environmental issues. Dealing with environmental issues is quickly moving out of the confines of corporate environmental departments into the realm of corporate financial strategy. The recent results from the emerging carbon markets are encouraging. In May 2006, the World Bank reported on the global market for trading carbon dioxide (CO2 ) emissions stating that in 2005 the overall value of the global aggregated carbon market was 10 times that of 2004. The World Bank reported for the first time that markets are pricing carbon, creating the opportunity for the private sector to efficiently support investments to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Additionally, analysts are now describing CO2 emissions as a financial market rather than the more traditional commodity market (Capoor and Amborsi, 2006). The primary event that dramatically increased 2005 global carbon dioxide trading volume was the emergence of Phase I of the European Union Emissions Trading System3 (EU ETS) that went into affect in January 2005 to address 25 European Union country Kyoto Protocol4 GHG emission reduction targets. -

Management for Sustainability: an Analysis of the Key Practices

Ecological Indicators 52 (2015) 116–127 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecological Indicators jo urnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolind Management for sustainability: An analysis of the key practices according to the business size a a,∗ b Clandia Maffini Gomes , Jordana Marques Kneipp , Isak Kruglianskas , a a Luciana Aparecida Barbieri da Rosa , Roberto Schoproni Bichueti a Santa Maria Federal University, Cidade Universitária, Av. Roraima, 1000, Prédio 74C, sala 4303, Santa Maria, RS Zip Code 97105-900, Brazil b São Paulo University, School of Economics, Business and Accounting, Luciano Gualberto 908, São Paulo, SP Zip Code 05508, Brazil a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: The mining sector has many challenges with regard to the incorporation of sustainability in the strategies Received 8 March 2014 and operations of the industry, given its extractive nature and the numerous social and environmental Received in revised form 11 August 2014 impacts related to this productive activity. Therefore, this study aims to analyze the relationship between Accepted 13 November 2014 the management practices for sustainability and business performance, according to the size of companies in the Brazilian mining sector. The study of descriptive and quantitative nature was conducted through a Keywords: survey with companies associated with the Brazilian Mining Association (IBRAM). The main results show Management for sustainability that larger companies indicate higher levels of adoption of management practices for sustainability and Performance Size business performance. The correlation analysis also allowed us to verify that the number of associations between the management practices for sustainability and business performance is higher in larger com- Mining sector panies.