Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What the Future Has in Store by Nick Bogaert and Brian Zeman

REGIONAL SPOTLIGHT The Milton area What the future has in store By Nick Bogaert and Brian Zeman The future looks bright for Milton as more recreational and natural areas are planned Future lands to be added to Conservation Halton ownership. Source: MHBC Planning This is the final article in a three-part series related to the area surrounding the Kelso and Hilton Falls Conservation areas in the Town of Milton . The first article examined the history of the Milton area with respect to aggregate extraction .The second reviewed present land uses and evolving recreation nodes near Highway 401 . In this final piece, we provide an overview of the future recreational land uses in the Milton area, which has been supplying key construction materials to the local economy since the 1800s . ituated in close proximity to two local quarries, the growing Town S of Milton has developed into a key recreation node, serving the western end of the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) and beyond. Conservation areas, golf courses, a large lake and ski hill provide a scenic outdoor playground for year-round recre- ational activities of all sorts – including some of the best hiking and biking in southern Ontario. 36 AVENUES REGIONAL SPOTLIGHT FUTURE RECREATIONAL NODE PLANS The good news is that along with population growth in the area, more Population growth recreational lands will be added as part • The Greater Toronto Area (GTA) is expected to grow by 2.7 million people by of the future rehabilitation of aggregate 2031, with an additional 1.4 million people between 2031 and 2041. -

Conservation Halton Parks

Conservation Halton Conservation Areas PAGE 2 • Kelso/Glen Eden (Ski Hill) • Rattlesnake Point • Hilton Falls • Mount Nemo • Mountsberg • Crawford Lake • Robert Edmonson Kelso Conservation Area PAGE 3 Attractions: • Kelso Lake/Beach • Challenge & aerial course • Ways of the Woods camps • Hiking/MTB Trails • Mountain Bike School Events: • Fall into Nature • Movie Nights • Hops & Harvest Festival • MTB Race Series • Cyclocross Race Series Activities: • Hiking • Mountain biking • Picnicking • Camping • Boating • Swimming • Fishing Glen Eden Ski Hill PAGE 4 Attractions: • 17 runs & 7 lifts • 3 Terrain Parks • Snow School Programs: • 8 week lessons • Discover lessons • Private lessons • Christmas camps • March Break camps Events: • Snow Show • Campfire Series Activities: • Skiing • Snowboarding Rattlesnake Point Conservation Area PAGE 5 Attractions: • Buffalo Crag, Pinnacle & Nassagaweya Canyon Lookouts • Ancient cedars • Nassagaweya Canyon trail Events: • Fall into Nature • Yoga in the Park • “Try It” Series (Rock Climbing) • Tai Chi in the Park Activities: • Hiking • Picnicking • Camping • Rock climbing • Cross-country skiing Hilton Falls Conservation Area PAGE 6 Attractions: • Waterfall • Bonfire at the falls • Mill ruins • Reservoir Events: • Fall into Nature • Winter on the Trails Activities: • Hiking • Mountain biking • Picnicking • Fishing • Cross-country skiing • Snowshoeing • Bird watching Mount Nemo Conservation Area PAGE 7 Attractions: • Brock Harris Lookout • Caves • Ancient cedars Events: • Fall into Nature • Meditation hikes Activities: -

2010 Season Summary Index NEW WOFTHE~ Zone 1: Yukon Territory

2010 Season Summary Index NEW WOFTHE~ Zone 1: Yukon Territory ........................................................................................... 3 Alaska ... ........................................ ............................................................... 3 LEPIDOPTERISTS Zone 2: British Columbia .................................................... ........................ ............ 6 Idaho .. ... ....................................... ................................................................ 6 Oregon ........ ... .... ........................ .. .. ............................................................ 10 SOCIETY Volume 53 Supplement Sl Washington ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3: Arizona ............................................................ .................................... ...... 19 The Lepidopterists' Society is a non-profo California ............... ................................................. .............. .. ................... 2 2 educational and scientific organization. The Nevada ..................................................................... ................................ 28 object of the Society, which was formed in Zone 4: Colorado ................................ ... ............... ... ...... ......................................... 2 9 May 1947 and formally constituted in De Montana .................................................................................................... 51 cember -

Ecommunicator - Fall 2018

eCommunicator - Fall 2018 Journal of 32 Signal Regiment eCommunicator Volume 18, Number 2 http://www.torontosignals.ca/ Merry Christmas Warmest thoughts and Best Wishes for a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year Table of Content About the eCommunicator 3 CO’s Message This is a limited domestic publication produced with 3 RSM’s Message the permission of the Commanding Officer for the purpose of recording the activities within the 4 Honouraries Message Regiment and the Regimental family. It is intended to provide a wide variety of material relating to Features military communications and military affairs, both 8 Awards and Promotions at home and abroad. 10 Re-dedication Ceremony of Coronation Park The views and opinions expressed in this periodical 11 17th Veterans Luncheon are those of the contributors and not those of the 12 Cipher Workshop at Dundurn Castle Department of National Defence, its Units or 13 Signals Birthday Officers, including the Commanding Officer of 32 14 Op LENTUS: Exploring Domestic Disaster Response Signal Regiment. 18 Technology Topic: Software-Defined Radio (SDR) The editor and publisher are responsible for the 21 Letters to the Editor production of the eCommunicator but not for the 22 Logistics Branch and RCEME Corps accuracy, timeliness or description of written and 23 709 Signals Army Cadet Corps graphical material published therein. 25 2250 The Muskoka Pioneers RCACC The editor reserves the right to modify or re-format 26 142 Mimico Determination Squadron material received, within reason, in order to make 28 Regimental Advisory Council best use of available space, appearance and layout. 30 Jimmy and Associates 33 Toronto Signals Band 32 Signal Regiment 34 Vintage Signals Team: Annual ARRL/RAC Field Day 35 Vintage Signals Team: Berlin 2018 Commanding Officer: 36 Memorial Line Truck LCol Alfred Lai, CD 37 709 (Signals) Toronto Army Cadet Corps: Casa Loma Regimental Sergeant Major: 38 Last Post CWO Steve Graham, CD Honorary Colonel: HCol Jim Leech, C.M. -

Master Plan for Rattlesnake Point Conservation Area Stage Three

Parks Master Planning Master Plan for Rattlesnake Point Conservation Area Stage Three Report OCTOBER I 2014 TCI Management Consultants Rattlesnake Point Conservation Area Approval Statement We are pleased to approve the Master Plan for Rattlesnake Point Conservation Area as the official policy document for the management and development of this conservation area. The plan reflects Conservation Halton’s intent to protect the natural environment of the Niagara Escarpment and the natural and cultural features of Rattlesnake Point Conservation Area and to maintain and develop high quality opportunities for outdoor education, recreation, discovery and enjoyment of the Niagara Escarpment by Ontario residents and visitors. _____________________________ ____________________________ Ken Phillips Date Chief Administrative Officer Conservation Halton _____________________________ ____________________________ John Vice Date Chair, Board of Directors Conservation Halton I am pleased to deem this master plan in conformity with the general intent and purpose of the Niagara Escarpment Plan (2005) pursuant to S. 13-(1) of the Niagara Escarpment Planning and Development Act. _____________________________ ____________________________ Deb Pella Keen Date Director Niagara Escarpment Commission _____________________________ ____________________________ Ray Pichette Date Director Natural Heritage Lands and Protected Spaces Branch Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry i Rattlesnake Point Conservation Area Preface The Master Plan for Rattlesnake -

The Iroquoian Newsletter

IROQUOA The Iroquoian Official Newsletter of the Iroquoia Bruce Trail Club SUMMER 2016 SIGHTS FROM THE AGM PHOTO CREDITS - MICHAEL MCDONALD Our AGM was held Sat. April 16th, and it was a great success. It was well attended, and everyone had a great time. The two proceeding hikes had fantastic weather and a great time exploring the Bruce Trail. A new board was ratified, and we made some minor changes to our club by-laws. Congratulations to the following recipients for their awards. Phill Armstrong: Volunteer Hike Leader Vern Erickson: Volunteer Hike Leader Errol Mackenzie: Co-ordinator and Hike Leader for Happy Wanderers Don Matheson: Volunteer Weekly Hike Leader Connie Rusynyk: Co-ordinator for Midweek Hikes/Hike Leader Nancy Stevens: Volunteer Weekly Hike Leader Charlotte Stewart: Co-ordindator and Hike Leader for Hikers R Us Trail Maintenance worker of the year went to a very deserving Peter Rumble. A special thanks to Deputy Environmental Commissioner of Ontario, Ellen Schwartzel for her talk on our environmental rights. IROQUOIA BOARD OF DIRECTORS 2015/2016 THE IROQUOIAN PRESIDENT Doug Stansbury 905-545-2715 The Iroquoian Newsletter is [email protected] published quarterly by the IBTC, 1st Vice-President & BTC Board Rep one of nine member clubs of the Paul Toffoletti - 905-634-2642 Bruce Trail Conservancy, a registered non-profit organization. Iroquoia Bruce Trail Club 2nd Vice-President & Director of PO Box 71507 Media We welcome submission of articles Michael McDonald 905-928-5324 Burlington, ON, L7T 4J8 [email protected] or photographs for publication from our members. All submissions will Hiking Director Anne Armstrong - 905-337-3937 be reviewed and must be approved [email protected] by the Board of Directors. -

Distribution of Fish Species at Risk

Maple Grove Connor Mount Wolfe Ballycroy Nobleton Airfield Lucille Jessopville Burbank Field Airfield Gibson Lake Hammertown Crombies Woodside Bailey Creek Distribution of Fish Humber River Camilla Hockley Valley Provincial Nature Reserve Park Palgrave Holly Park Glen Cross Palgrave Conservation Area Cannings Falls Mono Mills Dam Species at Risk Cold Creek Conservation Area East Humber River Nobleton King Creek Blacks Corners Cedar Mills Whittington Cardwell Hockley Valley Blount Castlederg Credit Valley Albion Hills Conservation Area Coventry Allens Lakes Mono Mills Conservation Authority Glen Haffy Conservation Area Salem (Map 1 of 2) Humber Springs Ponds Lockton The Dingle Hockley Valley Cold Creek Campania Grand Valley Airfield Albion Hills Albion Sleswick Humber Bolton Monora Creek Island's Bay Glasgow Sharon Lake Nottawasaga River Humber River Willow Brook Orangeville Reservoir Bolton Station Laurel Monora Conservation Area Centreville Creek Humber River ¤£25 Credit River Speersville Kleinburg Leggatt Tormore Orangeville Rosehill Widgett Lake Nashville Farmington Macville Bowling Green Mill Creek Innis Lake Twenty Five Hill Caledon East Melville Hill Star Grand River Fraxa Junction Mono Road Melville Pond Lindsay Creek Morrow's Hill Melville McLeodville Elder Mills 136 Coleraine ¤£ The Horse Shoe West Humber River Elder Station Garafraxa Woods Caledon Hills Warnock Lake Wildfield Tarbert McCallum's Pond Sandhill Silver Creek Little Credit River Amaranth Station Caledon Lake Caledon Village The Maples Cressview Lakes -

Where to Get Copies of Escarpment Views Along the Niagara Escarpment

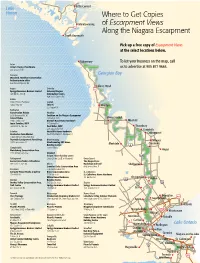

Lake • Little Current Huron Where to Get Copies Manitowaning of Escarpment Views 6• Along the Niagara Escarpment • South Baymouth Pick up a free copy of Escarpment Views at the select locations below. Tobermory To list your business on the map, call Acton • Acton Home Hardware us to advertise at 905 877 9665. 362 Queen St. E Ancaster Georgian Bay Woodend, Hamilton Conservation Authority main office 838 Mineral Springs Rd Lion’s Head Angus Grimsby 6• Spriggs Insurance Brokers Limited Gateway Niagara 189 Mill St., Unit B Information Centre 424 South Service Rd Bolton United Home Hardware Guelph 12833 Hwy 50 Solar G Wiarton 2-2 Taggart St • Burlington Conservation Halton Hamilton 2596 Britannia Rd. W Coalition on the Niagara Escarpment Ireland House 193 James St. S Owen Sound 2168 Guelph Line Dartnall Road Home Hardware • Meaford Joyce Savoline, MPP 10 Dartnall Rd • 760 Brant St., Ste. 44 Paul Miller, MPP • Thornbury 289 Queenston Rd Craigleith Caledon Westcliffe Home Hardware • Collingwood Heatherlea Farm Market Westcliffe Mall 632 Mohawk Rd • 17049 Winston Churchill Blvd Topnotch Consignment Furnishings Manitowaning Stayner 14034 Hurontario St Manitowaning Mill Home Markdale Creemore• Building Centre • 4 Campbellville 15874 Hwy 6 • Mountsberg Conservation Area • Angus 2259 Milburough Line Meaford Knights’ Home Building Centre 124 Collingwood 206532 Hwy 26 (E. of Meaford) Owen Sound Scenic Caves Nature Adventures The Ginger Press 269 Scenic Caves Rd Milton Bookshop and Café Shelburne Crawford Lake Conservation Area 848 Second Ave. E • Creemore 3115 Conservation Rd Curiosity House Books & Gallery Kelso Conservation Area St. Catharines 134-A Mill St 5234 Kelso Rd St. Catharines Home Hardware Milton Home Hardware 111 Hartzel Rd Orangeville Caledon Dundas Building Centre 109 • Dundas Valley Conservation Area, 385 Steeles Ave. -

Club Activities

Volume 41, Number 2 January-February 2007 Club Activities Indoor: Meetings begin at 7:30 pm on the second Tuesday of the month, October to June at St. Andrew’s United Church, 89 Mountainview Road South (at Sinclair) in Georgetown unless stated otherwise. Feb. 13: Central and South America, and the Bruce Peninsula. Bev Whatmough will be giving a presentation on some of the flora and fauna, and a look at the new Bruce Peninsula Park and Fathom Five Park interpretive centre. Mar. 13: Re-introduction of Elk into Ontario. Meagan Hazell will speak about her research on the release of large ruminants into Ontario Apr. 10: Halton Natural Areas Inventory. Andrea Dunn, Conservation Halton, will be talking on the results of the Sixteen Mile Creek Monitoring Study. Andrea was the coordinator of the project. Outdoor: Trips begin at the Niagara Escarpment Commission (NEC) parking lot at Guelph and Mountainview Road, Georgetown, unless stated otherwise. If you would like to meet the group at the trip site, please speak to the trip leader for the location and directions to the starting point. Jan. 21: Burlington Waterfowl. Meet 8:00 am. In case of inclement weather, check ahead with the trip leaders, Kelly Bowen and Andrew Kellman (905) 873-7338 Feb.18: Butterfly Conservatory, Niagara Falls, Ontario. Meet at the NEC parking lot at 8:00 am, or at the conservatory at about 9:30 am. Admission is $11 for adults. This should be a great opportunity to photograph butterflies and get a winter taste of the tropics! Depending on the weather and the group’s interests we may do some birding along the Niagara River or Lake Ontario in the afternoon. -

Trails May Be Closed Depending on Trail and Weather Conditions/Special Events

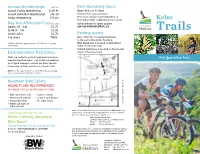

Annual Memberships (HST incl.) Park Operating Hours Annual Family Membership $129.95 Open Daily at 8:30am Annual Individual Membership $56.50 Closing times vary seasonally; Senior Membership 15% off Kelso trails may be closed depending on trail and weather conditions/special events. Kelso Day Use Admission Fees (HST incl.) Check website for latest updates Adults (15 - 64) $6.75 conservationhalton.ca Child (5 - 14) $5.00 Trails Senior (65+) $5.75 Parking Access 4 & under *FREE Kelso offers two convenient entrances to the park with plenty of parking; *Children 4 & under pay group rate of $2.00 when in a group Main Gatehouse is located on Kelso Road of 8 or more. (west of Tremaine Road) Summit Gatehouse is located on Steeles Ave (west of Tremaine Road) Environmental Trail Ethics Trails are routed to protect neighbouring environ- Find your place here. mentally sensitive areas. Trail routes are selected to mitigate damage to animal and plant species. Please stay on trails and do not cut new trails. NOTE: The Escarpment Rim Trail is CLOSED to Mountain Biking due to safety and environmental concerns. Summit Entrance Mountain Bike Safety Stone HELMETS ARE RECOMMENDED Kas OFF-ROAD CYCLIST RESPONSIBILITY CODE biker: of • Ride open trails only • Leave no trace • Never spook animals • Control your bicycle photo • Always yield trail • No night riding • Riders use trails at Cover their own risk Kelso conservation Area is part of more than 2,400 hectares of Come and join the fun at conservation lands that are being protected and are available for recreational and educational experiences. -

Forest Health Conditions in Ontario 2019 Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry September 22, 2020 Page 2 of 163 C 5 - CW Info

September 22, 2020 Page 1 of 163 C 5 - CW Info Forest Health Conditions in Ontario 2019 Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry September 22, 2020 Page 2 of 163 C 5 - CW Info Forest Health Conditions in Ontario 2019 Compiled by: • Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Science and Research Branch © 2020, Queen’s Printer for Ontario Printed in Ontario, Canada Find the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry online at ontario.ca. For more information about forest health monitoring in Ontario visit ontario.ca/page/forest-health-conditions. Cette publication hautement spécialisée, Forest Health Conditions in Ontario 2019, n’est disponible qu’en anglais conformément au Règlement 671/92, selon lequel il n’est pas obligatoire de la traduire en vertu de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir des renseignements en français, veuillez communiquer avec le ministère des Richesses naturelles et des Forêts au [email protected]. Some of the information in this document may not be compatible with assistive technologies. If you need any of the information in an alternate format, please contact [email protected]. ISBN 978-1-4868-4585-9 (pdf) i September 22, 2020 Page 3 of 163 C 5 - CW Info Contents Contributors ..................................................................................................................... iii État de santé des forêts en 2019 ...................................................................................... iv Introduction ...................................................................................................................... -

Master Plan for Mount Nemo Conservation Area Stage Three Report Parks Master Planning

Parks Master Planning Master Plan for Mount Nemo Conservation Area Stage Three Report JANUARY| 2014 TCI Management Consultants Mount Nemo Conservation Area Preface The Master Plan for Mount Nemo Conservation Area is the principal guiding policy document for the planning, development and resource management of Mount Nemo Conservation Area, which is owned and administered by Conservation Halton. This master plan has been undertaken as recommended by the Limestone Legacy report prepared by Conservation Halton in 2007, which proposed a vision to create “a sustainable network of world class conservation parks for ecological health and to provide public green space for quality education and recreation.” The vision, goals and objectives of that plan are attached to this report as Appendix III. This plan was developed in a phased three stage planning process that was designed to address growing regional recreational demands while also ensuring the long-term protection and sustainability of this natural escarpment area. The planning process was structured to satisfy the legislative requirements of the Niagara Escarpment Plan (2005) and the Conservation Authorities Act and has included extensive consultation with the public, stakeholders and related agencies. Final approval of this plan is under the jurisdiction of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources in accordance with the Niagara Escarpment Plan (2005). Upon approval of this document by the Board of Conservation Halton, submission is made to the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Niagara Escarpment Commission for review, circulation and final approval by the Minister or designate of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. The Master Plan will be the prevailing policy document for the next ten years from the date of MNR approval.