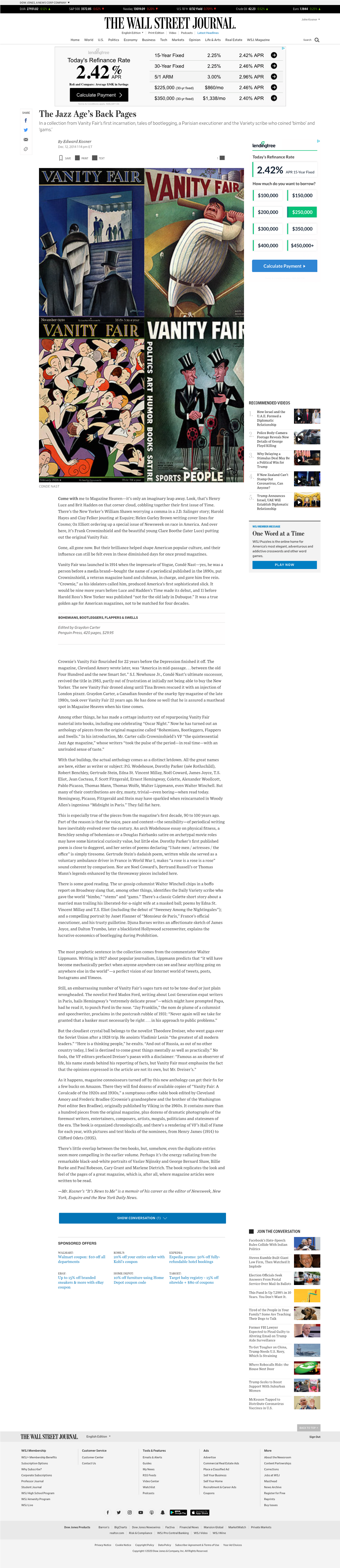

"Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells" by Graydon Carter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examining the Magazine Industry Standard

POINT OF VIEW: EXAMINING THE MAGAZINE INDUSTRY STANDARD A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by CRISTINA DAGLAS John Fennell, Thesis Supervisor MAY 2009 © Copyright by Cristina Daglas 2009 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled POINT OF VIEW : EXAMINING THE MAGAZINE INDUSTRY STANDARD presented by Cristina Daglas, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor John Fennell Professor Jennifer Rowe Professor Amanda Hinnant Professor Maureen Stanton ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am immensely grateful to my thesis chair, John Fennell, who believed in both the necessity for and the feasibility of this research. When many doubted the ability to interview prominent magazine professionals, John provided support and guidance while always keeping setbacks and successes in perspective. John has been a mentor from first semester of graduate school when I enrolled in his writing course, and I am so pleased that I could pursue a topic I am incredibly passionate about with his guidance. However, this research would naturally not be what it is without the rest of my fabulous committee. Jennifer Rowe, my other mentor, adviser and friend, was an invaluable resource, as she provided big-picture edits, line edits and, most importantly, support. Amanda Hinnant provided advice in the earliest days of thesis conception as well as the scholarly perspective necessary in any academic work. Maureen Stanton was also a wonderful resource, imparting an outside, nonfiction mindset that added another dimension to this journalistic thesis. -

2015 New York Journalism Hall of Fame

THE DEADLINE CLUB New York City Chapter, Society of Professional 2015 Journalists NEW YORK JOURNALISM HALL OF FAME SARDI’S RESTAURANT, 234 WEST 44TH ST., MANHATTAN Thursday, Nov. 19, 2015 11:30 a.m. reception Noon luncheon 1 p.m. ceremony PROGRAM WELCOME J. Alex Tarquinio MENU Deadline Club Chairwoman REMARKS APPETIZER Peter Szekely Deadline Club President Sweet Corn Soup with Crab and Avocado Paul Fletcher ENTREE Society of Professional Journalists President Sauteed Black Angus Sirloin Steak with Parmesan Whipped Potatoes, Betsy Ashton Porcini Parsley Custard and Classic Bordelaise Sauce, Deadline Club Past President Seasonal Vegetables THE HONOREES MAX FRANKEL DESSERT The New York Times Molten Chocolate Cake JUAN GONZÁLEZ with Pistachio Ice Cream The New York Daily News CHARLIE ROSE CBS and PBS LESLEY STAHL CBS’s “60 Minutes” PAUL E. STEIGER ProPublica and The Wall Street Journal RICHARD B. STOLLEY Time Inc. FOLLOW THE CONVERSATION ON TWITTER WITH THE HASHTAG #deadlineclub. PROGRAM WELCOME J. Alex Tarquinio MENU Deadline Club Chairwoman REMARKS APPETIZER Peter Szekely Deadline Club President Sweet Corn Soup with Crab and Avocado Paul Fletcher ENTREE Society of Professional Journalists President Sauteed Black Angus Sirloin Steak with Parmesan Whipped Potatoes, Betsy Ashton Porcini Parsley Custard and Classic Bordelaise Sauce, Deadline Club Past President Seasonal Vegetables THE HONOREES MAX FRANKEL DESSERT The New York Times Molten Chocolate Cake JUAN GONZÁLEZ with Pistachio Ice Cream The New York Daily News CHARLIE ROSE CBS and PBS LESLEY STAHL CBS’s “60 Minutes” PAUL E. STEIGER ProPublica and The Wall Street Journal RICHARD B. STOLLEY Time Inc. FOLLOW THE CONVERSATION ON TWITTER WITH THE HASHTAG #deadlineclub. -

Extensions of Remarks E1692 HON. BLAINE LUETKEMEYER HON

E1692 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks December 13, 2017 MSgt McAnulty was selected for service with Ribbon, the Kuwait Liberation Medal, the Ma- PERSONAL EXPLANATION Marine Security Guard Battalion. Later he was rine Security Guard Ribbon (3rd Award), the assigned to Marine Security Guard detach- Expert Pistol (6th Award), and the Expert Rifle HON. LUIS V. GUTIE´RREZ ments in Asuncion, Paraguay, Seoul, Korea, (9th Award). OF ILLINOIS and Budapest, Hungary. In 1996, orders MSgt McAnulty is survived by his parents, IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES brought him to 1st Marine Division, Camp Robert and Frances McAnulty; brother and Pendleton, California, for duty with 2nd Bat- sister-in-law, Brett and Stacy McAnulty; and Wednesday, December 13, 2017 talion, 4th Marines. During that same assign- his two nieces, Cora McAnulty and Lily Mr. GUTIE´ RREZ. Mr. Speaker, I was un- ment, he deployed with Battalion Landing McAnulty. avoidably absent in the House chamber for Team 2/4 as part of the 31st Marine Expedi- MSgt McAnulty distinguished himself Roll Call votes 674 and 675 on Tuesday, De- tionary Unit from November 1998 until April throughout his military career. His service and cember 12, 2017. Had I been present, I would 1999. sacrifice will always be remembered. have voted Yea on Roll Call vote 674 and Nay MSgt McAnulty would further distinguish on 675. himself in 2001. When he was reassigned to f Marine Security Guard Battalion and trained to f serve in the coveted position of detachment CONGRATULATING BRIANNA commander. MSgt McAnulty commanded Ma- HALLER OF THE FATIMA COM- RECOGNIZING THE LIFE OF FALL- rine Security Guard detachments at U.S em- ETS CROSS COUNTRY TEAM EN SOLDIER ARMY STAFF SER- bassies in war-torn Bujumbura, Burundi, and GEANT (SSG) MILTON RIVERA- in the dangerous city of Bogota, Colombia. -

National Magazine Award

VIRTUAL PRESENTATION | THURSDAY, MAY 28, 2O2O The National Magazine Awards honor print and digital publications that consistently demonstrate superior execution of editorial objectives, innovative techniques, noteworthy enterprise and imaginative design. Originally limited to print NATIONAL MAGAZINE AWARDS FOR PRINT AND DIGITAL MEDIA magazines, the awards now recognize magazine-quality ASME Award for Fiction | Honoring The Paris Review journalism published in any medium. Founded in 1966, the awards ASME NEXT Awards for Journalists Under 30 are sponsored by the American Society of Magazine Editors Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame Award | Honoring David Granger in association with the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and are administered by ASME. Awards are presented in 22 categories. The winner in each category receives an “Ellie,” modeled on the symbol of the awards, ASME.MEDIA TWITTER.COM/ASME1963 #ELLIES Alexander Calder’s stabile “Elephant Walking.” | | THE OSBORN ELLIOTT-NATIONAL MAGAZINE AWARDS SCHOLARSHIP INFORMATION ABOUT FINALISTS AND WINNERS Ellie Awards 2020 ticket sales provide support for the Please visit asme.media for more information about Ellie Awards 2020 Osborn Elliott Scholarship at the Columbia Journalism School. honorees, including citations, links to content and a complete list of the judges Named for the former Newsweek editor and Editors whose names appear in citations held those positions Columbia dean, the scholarship is awarded to students who or were listed on the masthead when the content was published. intend to pursue careers in magazine journalism. Other editors may now be in those positions Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame Helen Gurley Brown Tina Brown William F. Buckley Jr. Gayle Goodson Butler Graydon Carter MAGAZINE John Mack Carter Sey Chassler EDITORS’ Arthur Cooper Byron Dobell HALL OF FAME Osborn Elliott Clay Felker Dennis Flanagan Henry Anatole Grunwald The Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame Hugh M. -

DAVID TEDESCHI Editor

DAVID TEDESCHI Editor PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS PRETEND IT’S A CITY Martin Scorsese NETFLIX Documentary Series Emma Tillinger Koskoff Josh Porter UNTITLED SCTV DOCUMENTARY Martin Scorsese Emma Tillinger Koskoff ROLLING THUNDER REVUE Martin Scorsese Jeff Rosen, Margaret Bodde VINYL Martin Scorsese SIKELIA PRODUCTIONS / HBO Pilot Mari Jo Winkler AMERICAN DREAM / Antoine Fuqua PHOENIX PICTURES AMERICAN KNIGHTMARE SHOWTIME Brad Fischer, Eva Gunz GEORGE HARRISON: Martin Scorsese Margaret Bodde, Nigel Sinclair LIVING IN THE MATERIAL WORLD Nominee, Best Doc. Editing – Emmy Awards Nominee, Best Doc. Editing – ACE Eddies PUBLIC SPEAKING Martin Scorsese HBO FILMS Margaret Bodde, Graydon Carter Fran Lebowitz THE ROLLING STONES: SHINE A LIGHT Martin Scorsese Zane Weiner, Mick Jagger NO DIRECTION HOME: BOB DYLAN Martin Scorsese Jeff Rosen, Jessica Cohen Nomination, Outstanding Editing – Emmy Awards EL CANTANTE Leon Ichaso Simon Fields THE SHIELD Various Directors FX Series, One Season Scott Brazil, Shawn Ryan THE BLUES: FEEL LIKE GOING HOME Martin Scorsese PBS Sam Pollard, Alex Gibney PINERO Leon Ichaso MIRAMAX John Penotti AMERICAN HIGH R.J. Cutler FOX Pilot & Series Dan Partland Henriette Mantel THE AWFUL TRUTH Michael Moore BRAVO Series EL SILENCIO DE NETO Luis Argueta MORNINGSIDE MOVIES Official Selection – Sundance Film Festival Adrian Grunberg FREE OF EDEN Leon Ichaso SHOWTIME Cedric Scott AZUCAR AMARGA Leon Ichaso FIRST LOOK PICTURES Jaime Pina AMERICA’S CHALLENGE Barbara Kopple CABIN CREEK FILMS TV NATION Series Michael Moore FOX Winner, Outstanding Non-Fiction Program Emmy Awards INNOVATIVE-PRODUCTION.COM | 310.656.5151 . -

Chapter 1 Paulie!

Chapter 1 Paulie! Blanca! Lola! Christopher! Over here! How about one of the Santisi family all together!” the paparazzi shout as we’re bathed in a meteor shower of flashing lights. It’s blinding as we make our way down the photo-frenzied Red Carpet for Vanity Fair’s annual post-Oscar bash—Hollywood’s primo party of the year. My mother tugs my older brother, Christopher, and me to her and shoots her husband a pleading look. “Please, Paulie, just one of the four of us,” her blood red lips purr, her Mediterranean-colored eyes sparkling through the smoky Paris-runway-ready eye shadow that François Nars himself applied not five hours ago at Villa Santisi. “We can put it on the Christmas card.” Only my crazy Jewish mother would send out Christmas cards—from the VF Red Carpet. Even if we’re not the perfect Norman Rockwell family, my mother would like us to pose for the cameras as if we were. I swear my mother could stand here all night as if she’d won her own Oscar, pirouetting and fanning out the skirt of her shocking pink ruffled satin Chanel gown for the photographers, canting one olive Pilates’d thigh forward (“Slims the profile, Lola, you should try it”). Even the black diamond Neil Lane dragonfly pinning back her shoulder- length platinum hair seems to be begging for a photo. She’s acting like she’s back in Irving Penn’s studio posing for one of the many 1970s Vogue covers she graced. My father rolls his eyes. -

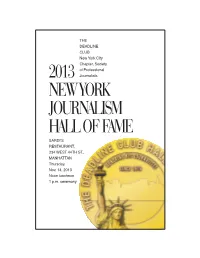

HOF Program 2013

THE DEADLINE CLUB New York City Chapter, Society of Professional 2013 Journalists NEW YORK JOURNALISM HALL OF FAME SARDI’S RESTAURANT, 234 WEST 44TH ST., MANHATTAN Thursday, Nov. 14, 2013 Noon luncheon 1 p.m. ceremony MENU APPETIZER Sweet Corn Soup with Crab and Avocado ENTREE Sauteed Black Angus Sirloin Steak with Parmesan Whipped Potatoes, Porcini Parsley Custard and Classic Bordelaise Sauce, Seasonal Vegetables DESSERT Molten Chocolate Cake with Pistachio Ice Cream PROGRAM WELCOME J. Alex Tarquinio Deadline Club President REMARKS Betsy Ashton Deadline Club Past President INDUCTION OF THE 2013 HONOREES Cindy Adams Jimmy Breslin Graydon Carter Bob Herbert Carol Loomis Linda Mason Bill Moyers Norman Pearlstine FOLLOW THE CONVERSATION ON TWITTER WITH THE HASHTAG #deadlineclub Cindy Adams Jimmy Breslin Graydon Carter Bob Herbert THE 2013 HONOREES CINDY ADAMS has written a gossip column for the New York Post for more than 30 years. She has contributed to various TV programs including WNBC’s “Live at Five” and ABC’s “Good Morn- ing America.” Adams has written seven books, including biogra- phies of the acting teacher Lee Strasberg and the Kennedy clan matriarch Rose Kennedy, and even a memoir about her dog Jazzy. She has been inducted into the New York Women in Communica- tions Matrix Hall of Fame. JIMMY BRESLIN has covered New York for more than fifty years as a columnist for the Daily News, Newsday and New York magazine, among others. He is often remembered for an innova- tive article he wrote for the Herald Tribune in 1963 about John F. Kennedy’s gravedigger. A prolific author, his books include “The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight” and “Branch Rickey: A Life.” He has won numerous awards, including the George Polk Award for Metropolitan Reporting and a Pulitzer Prize for Commentary. -

New Establishment Summit

THE VANITY FAIR NEW ESTABLISHMENT SUMMIT The Vanity Fair New Establishment is the ultimate arbiter of the most COVER IMAGE (Clockwise from top left): influential names in the worlds of technology, media, the arts, and entertainment. Elon Musk, Kamala D. Harris, Katie Couric, Evan Spiegel, Jonathan Ive, Eric Schmidt, Last year marked not only the 20th anniversary of the New Establishment Michael Bloomberg, Bob Iger, issue but also the launch of Vanity Fair’s new annual franchise: the Vanity Fair Jeremy Stoppelman, Salman Khan, Laura Arrillaga-Andreessen, New Establishment Summit, in association with the Aspen Institute. Jack Dorsey, Gwynne Shotwell, Sophia Amoruso, Judd Apatow, Bob Woodward, Unlike other conferences in Silicon Valley, the V.F. Summit is devoted to and Mellody Hobson. creating a dialogue around a range of subject matter—technology, media and entertainment, business, politics, and global affairs—debated by a powerful ABOVE group of speakers to an equally impressive audience. (Clockwise from top left): Elon Musk, Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, Melinda Gates, Ralph Lauren, Jack Dorsey, Stephen Colbert, Natalie Massenet, George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, George Clooney, Jay Z, Sheryl Sandberg, Jonathan Ive, Marc Newson, Diane Sawyer, Barbara Walters, and Oprah Winfrey. V.F. SUMMIT 2014 LOCATION Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco Judd Apatow and Jonathan Ive and George Lucas DATES Graydon Carter October 8 and 9, 2014 ATTENDEES (SOLD OUT) 320 STUDENTS 300 over the course of two days (from local Bay Area universities, including U.C. Berkeley, Stanford, Academy of Art University, etc.) Bob Iger and Jack Dorsey Larry Page and Michael Bloomberg Audience members Elon Musk and Walter Isaacson SPEAKERS & ATTENDEES Some of the country’s most influential men and women were among the attendees both on stage and in the audience. -

Martin Scorsese and Film Culture

Martin Scorsese and Film Culture: Radically Contextualizing the Contemporary Auteur by Marc Raymond, B.A., M.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Comparative Studies in Literature, Art and Culture: Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Canada January, 2009 > 2009, Marc Raymond Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-47489-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-47489-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

The City Secrets Travel Series Arts & Letters Series About City Secrets

FANG DUFF KAHN PUBLISHERS 611 BROADWAY, FL 4 FANGDUFFKAHN.COM P. 212-473-0098 F. 212-353-1933 THE CITY SECRETS TRAVEL SERIES “The best literary gift to Italian travelers since the Baedeker and Henry James.” —Financial Times “This idiosyncratic guide helps jaded visitors see the Eternal City anew.”—New York Times “The future of guidebooks.”—Good Magazine “City Secrets New York City, the latest installment in architect Robert Kahn’s invaluable series of insider guides for travelers, comprises recommendations from more than 300 writers, artists, historians, gourmands, and other notables . ”—New York Magazine “Escape from the crowds and chaos can be a challenge in Rome, but help comes in the form of City Secrets Rome. Architect and former resident Robert Kahn has collected the wisdom of his artist and writer friends in a guide that peels back the layers of the city’s charms.”—Condé Nast Traveler ARTS & LETTERS SERIES “A wonderfully subjective little guide to the best films of all time.” —Graydon Carter, Vanity Fair “What a superb literary map . within, even the most jaded readers can find marvels.”—Junot Diaz “Movies: The Ultimate Insider’s Guide is an offbeat, expertly curated compendium of hundreds of movies you may have missed.” — Veryshortlist.com “Two new clothbound handbooks, Movies: The Ultimate Insider’s Guide and Books: The Essential Insider’s Guide, are page-turning compendiums of overlooked great works, the latest from the coveted City Secrets series of guidebooks.”—PaperMagazine.com ABOUT CITY SECRETS City Secrets Travel and City Secrets Arts & Letters is based on one concept: each book is a compilation of short essays written by notable contributors about overlooked or underappreciated places, movies, or books. -

J 335F Magazine Writing/Production 07785 Fall 2019 Prerequisites

J 335F Magazine Writing/Production 07785 Fall 2019 Prerequisites: Journalism 310F and 311F with a grade of at least B- in each. Class Meets: 2 p.m.-3:30 p.m. Tuesdays and Thursdays Room: CMA 4.152 Instructor: Kathy Blackwell Email: [email protected] Twitter: @kathyblackwell Office Hours: Thursdays, 1-2 p.m. and by appointment. I encourage everyone to come visit me at the magazine this semester. Overview Welcome to magazine writing and production! In this class, we’ll explore the art of magazine writing— from long-form narratives and in-depth profiles to oral histories, essays, service features, lists, reviews, tight-and-bright pieces, and everything in between. We’ll also look at the industry as a whole—where it’s been, what’s working, what isn’t, and what the future might hold. You have the equivalent of a front-row seat in this rapidly changing world. I’m a full-time magazine editor at Texas Monthly (official title: executive editor), so when I’m not with you, I’m in my office on Congress Avenue or out working on stories. If there’s a hot trending topic or interesting anecdote to share that is relevant to our class, I might switch things up a bit. It’s all in the name of helping you understand the magazine world as a whole, which is exciting and challenging and changes daily. You’ll notice there are a few days this semester where we won’t have class—those are when I expect to be on final deadline for an issue. -

How to Make Enemies and Influence People

BG CONVERSATION didn’t want to tell you, but I was a great friend of Lucan’s, and nobody has ever found out [what TT: Awful. So he calls me up and we have a chat. He asked if Vanity Fair paid for the party. I said, happened]. Everybody knows, had the statute of limitations run out, I would have spilled the beans. “Don’t put this in the paper; nobody paid for the party.” Nevertheless they ran it. [Hardcastle’s item R E I cast doubt on Taki’s denial and claimed Carter helped draw up the guest list. In a subsequent col- L BG: This was when you wrote about Lucan for Vanity Fair, Nick? E umn, he described Dunne as an “octagenarian lounge lizard,” Taki as a “furtive, olive-skinned crea- H C DD: Yes. ture,” his guests as “grotesque Eurotrash rabble,” and the resulting article as “a two sickbags mas- R ? A terpiece of sycophancy.”] That’s typically English. You tell them black, they write white, and vice- Y M TT: B I had volunteered to go and take care of that killer who murdered Nick’s daughter, who went E versa. Nothing very surprising. Which doesn’t matter at all. When the tax people come after me, H D free, and I really meant it, because I was so…I’d just had a daughter, and I was so upset when I P K I’ll just tell them there’s nothing to tell! A C read the story that Nick had written about it [Dunne’s debut as a writer, in 1982, decried the R I R G BG: T three-year sentence his daughter’s killer received] that I said to him that I could kill that S.O.B.