Emotional Labor and Prostitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unusual Sexual Behavior

UNUSUAL SEXUAL BEHA VIOR UNUSUAL SEXUAL BEHAVIOR THE STANDARD DEVIATIONS By DAVID LESTER, Ph.D. R ichard Stockton State College Pomona, New Jersey CHARLES C THOMAS • PUBLISHER Springfield • Illinois • U.S.A. Published and Distributed Throughout the World by CHARLES C THOMAS. PUBLISHER Bannerstone House 301-327 East Lawrence Avenue, Springfield, I1!inois, U.S.A. This book is protected by copyright. No part of it may be reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher. ©1975, by CHARLES C THOMAS. PUBLISHER ISBN 0-398-03343-9 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 74 20784 With THOMAS BOOKS careful attention is given to all details of manufacturing and design. It is the Publisher's desire to present books that are satisfactory as to their physical qualities and artistic possibilities and appropriate for their particular use. THOMAS BOOKS will be true to those laws of quality that assure a good name and good will. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Lester, David, 1942- Unusual sexual behavior. Includes index. 1. Sexual deviation. I. Title. [DNLM: 1. Sex deviation. WM610 L642ul RC577.IA5 616.8'583 74-20784 ISBN 0-398-03343-9 Printed in the United States of America A-2 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this book is to review the literature on sexual deviations. Primarily the review is concerned with the research literature and not with clinical studies. However, occasional refer ence is made to the conclusions of clinical studies and, in particular, to psychoanalytic hypotheses about sexual deviations. The coverage of clinical and psychoanalytic ideas is by no means intended to be exhaustive, unlike the coverage of the research literature. -

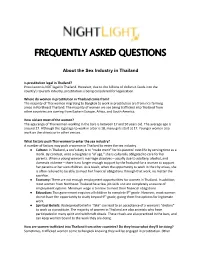

Frequently Asked Questions

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS About the Sex Industry in Thailand Is prostitution legal in Thailand? Prostitution is NOT legal in Thailand. However, due to the billions of dollars it feeds into the country’s tourism industry, prostitution is being considered for legalization. Where do women in prostitution in Thailand come from? The majority of Thai women migrating to Bangkok to work in prostitution are from rice farming areas in Northeast Thailand. The majority of women we see being trafficked into Thailand from other countries are coming from Eastern Europe, Africa, and South America. How old are most of the women? The age range of Thai women working in the bars is between 17 and 50 years old. The average age is around 27. Although the legal age to work in a bar is 18, many girls start at 17. Younger women also work on the streets or in other venues. What factors push Thai women to enter the sex industry? A number of factors may push a woman in Thailand to enter the sex industry. ● Culture: In Thailand, a son’s duty is to “make merit” for his parents’ next life by serving time as a monk. By contrast, once a daughter is “of age,” she is culturally obligated to care for her parents. When a young woman’s marriage dissolves—usually due to adultery, alcohol, and domestic violence—there is no longer enough support by the husband for a woman to support her parents or her own children. As a result, when the opportunity to work in the city arises, she is often relieved to be able to meet her financial obligations through that work, no matter the sacrifice. -

The Effects of Workplace Loneliness on Work Engagement and Organizational Commitment: Moderating Roles of Leader-Member Exchange and Coworker Exchange

sustainability Article The Effects of Workplace Loneliness on Work Engagement and Organizational Commitment: Moderating Roles of Leader-Member Exchange and Coworker Exchange Hyo Sun Jung 1 , Min Kyung Song 2 and Hye Hyun Yoon 2,* 1 Center for Converging Humanities Kyung Hee University, Seoul 02447, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Culinary Arts and Food Service Management, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 02447, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This study aims to examine the effect of workplace loneliness on work engagement and organizational commitment and the moderating role of social relationships between an employee and his or her superior and coworkers in such mechanisms. Workplace loneliness decreased employees’ engagement with their jobs and, as such, decreased engagement had a positive relationship with organizational commitment. Also, the negative influence of workplace loneliness on work engage- ment was found to be moderated by coworker exchange, and employees’ maintenance of positive social exchange relationships with their coworkers was verified to be a major factor for relieving the negative influence of workplace loneliness. Keywords: workplace loneliness; work engagement; organizational commitment; leader-member exchange; coworker exchange; deluxe hotel Citation: Jung, H.S.; Song, M.K.; Yoon, H.H. The Effects of Workplace 1. Introduction Loneliness on Work Engagement and Organizational Commitment: Workplace loneliness does harm to an organization as well as its employees [1]. In an Moderating Roles of Leader-Member organization, employees perform their jobs amid diverse and complex interpersonal rela- Exchange and Coworker Exchange. tionships, and if they fail to bear such relationships in a basic social dimension, they will be Sustainability 2021, 13, 948. -

Sex Work in Asia I

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION Regional Office for the Western Pacific SSEEXX WWOORRKK IINN AASSIIAA JULY 2001 SSeexx WWoorrkk IInn AAssiiaa Contents Acknowledgements ii Abbreviations iii Introduction 1 Sources and methodology 1 The structure of the market 2 The clients and the demand for commercial sex 3 From direct to indirect prostitution – and the limitations of statistical analysis 5 Prostitution and the idea of ‘choice’ 6 Trafficking, migration and the links with crime 7 The demand for youth 8 HIV/AIDS 9 Male sex workers 10 Country Reports Section One: East Asia Japan 11 China 12 South Korea 14 Section Two: Southeast Asia Thailand 15 Cambodia 17 Vietnam 18 Laos 20 Burma 20 Malaysia 21 Singapore 23 Indonesia 23 The Philippines 25 Section Three: South Asia India 27 Bangladesh. 30 Sri Lanka 31 Nepal 32 Pakistan 33 Sex Work in Asia i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS WHO wish to thank Dr. Louise Brown for her extensive research and preparation of this report. Special thanks to all those individuals and organisations that have contributed and provided information used in this report. Sex Work in Asia ii ABBREVIATIONS AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome FSW Female sex worker HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus MSM Men who have sex with men MSW Male sex worker NGO Non-governmental organisation STD Sexually transmitted disease Sex Work in Asia iii INTRODUCTION The sex industry in Asia is changing rapidly. It is becoming increasingly complicated, with highly differentiated sub sectors. The majority of studies, together with anecdotal evidence, suggest that commercial sex is becoming more common and that it is involving a greater number of people in a greater variety of sites. -

Social Work As an Emotional Labor: Management of Emotions in Social Work Profession

SOCIAL WORK AS AN EMOTIONAL LABOR: MANAGEMENT OF EMOTIONS IN SOCIAL WORK PROFESSION Associate Prof. Emine ÖZMETE* Abstract This paper provides a conceptual explanation of social work as emotional labor related to the interactions between social workers and their clients in human service organizations. Emotional labor is a relatively new term. It is about controlling emotions to conform to social and professionals norms. The concept of emotional labor offers researchers a lens through which these interactions can be conceived of as job demands rather than as a medium through which work tasks are accomplished or as informal social relations. This powerful insight has informed studies of interactive work in all its forms, as well as called attention to the many ways that interaction at work is organized, regulated, and enacted. Therefore understanding the interactions between clients and professional influences on the construction and regulation of emotion at work are important challenges for the social work profession. Key Words: Emotional labor, management of emotions, social work Özet Bu makalede insani hizmet örgütlerinde sosyal hizmet uzmanları ve müracatçılar arasındaki etkileşime dayalı olarak sosyal hizmetin duygusal bir iş olduğunu belirten kavramsal çerçeve açıklanmaktadır. Duygusal iş oldukça yeni bir kavramdır. Bu kavram, sosyal ve mesleki normlarla uyumlu olarak duyguların kontrol edilmesi ile ilişkilidir. Duygusal iş kavramı araştırmacılara basit bir şekilde informal sosyal ilişkiler ve yerine getirilmesi gereken bir işten daha çok iş taleplerinin gereği olarak ortaya çıkan etkileşimler için derinlemesine bir bakış açısı sunar. Bu güçlü bakış açısı günümüze değin yapılmış çalışmalarda etkleşime dayalı olarak planlanmış, düzenlenmiş ve gerçekleştirilmiş olan işler için kullanılmıştır. Bu nedenle müracatçılar ve meslek elemanları arasındaki etkileşimin iş yaşamında duyguların düzenlenmesi ve yapılandırılması üzerindeki etkisinin anlaşılması sosyal hizmet mesleği için önemli mücadele alanıdır. -

Homelessness, Survival Sex and Human Trafficking: As Experienced by the Youth of Covenant House New York

Homelessness, Survival Sex and Human Trafficking: As Experienced by the Youth of Covenant House New York May 2013 Jayne Bigelsen, Director Anti-Human Trafficking Initiatives, Covenant House New York*: Stefanie Vuotto, Fordham University: Tool Development and Validation Project Coordinators: Kimberly Addison, Sara Trongone and Kate Tully Research Assistants/Legal Advisors: Tiffany Anderson, Jacquelyn Bradford, Olivia Brown, Carolyn Collantes, Sharon Dhillon, Leslie Feigenbaum, Laura Ferro, Andrea Laidman, Matthew Jamison, Laura Matthews-Jolly, Gregory Meves, Lucas Morgan, Lauren Radebaugh, Kari Rotkin, Samantha Schulman, Claire Sheehan, Jenn Strashnick, Caroline Valvardi. With a special thanks to Skadden Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP and Affiliates for their financial support and to the Covenant House New York staff who made this report possible. And our heartfelt thanks go to the almost 200 Covenant House New York youth who shared their stories with us. *For questions on the use of the trafficking screening tool discussed in this report or anything else related to the substance of the study, please contact study author, Jayne Bigelsen at [email protected] Table of Contents: Executive Summary . 5 Introduction . 5 Key Findings . 6 Terminology . 7 Objectives/Method . 8 Results and Discussion . 10 Compelled Sex Trafficking . 10 Survival Sex . 11 Relationship between Sex Trafficking and Survival Sex . 12 Labor Trafficking . 13 Contributing Factors . 14 Average Age of Entry into Commercial Sexual Activity . 16 Transgender and Gay Youth . 16 Development and Use of the Trafficking Assessment Tool . 17 Implications for Policy and Practice . 19 Conclusion . 21 Appendix: Trafficking Screening Tool . 22 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction In recent years, the plight of human trafficking victims has received a great deal of attention among legislators, social service providers and the popular press. -

Norma Jean Almodovar 8801 Cedros Ave

Norma Jean Almodovar 8801 Cedros Ave. Unit 7 Panorama City, CA 91402 Phone: 818-892-2029 Fax: 818-892-2029 call first E-Mail: [email protected] Norma Jean Almodovar is a well known and highly respected international sex worker rights activist and is a popular speaker and published author, including articles in law journals and academic publications. She is currently engaged in researched for a book which exposes the unfortunate and harmful consequences of arbitrary enforcement of prostitution laws. From 1972 to 1982, she was a civilian employee of the Los Angeles Police Department, working as a traffic officer primarily in the Hollywood Division. There she encountered serious police abuse and corruption which she documented in her autobiography, Cop to Call Girl (1993- Simon and Schuster). In 1982 she was involved in an on-duty traffic accident, and being disillusioned by the corruption and societal apathy toward the victims of corruption, she decided not to return to work in any capacity with the LAPD. Instead, she chose to become a call girl, a career that would both give her the financial base and the publicity to launch her crusade against police corruption, particularly when it involved prostitutes. Unfortunately, she incurred the wrath of the LAPD and Daryl Gates when it became known that she was writing an expose of the LAPD, and as a result, she was charged with one count of pandering, a felony, and was ultimately incarcerated for 18 months. During her incarceration, she was the subject of a “60 Minutes” interview with Ed Bradley, who concluded that she was in prison for no other reason than that she was writing a book about the police. -

Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ This is an author produced version of a paper published in Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/3349/ Published paper Kieran, M. (2002) On Obscenity: The Thrill and Repulsion of the Morally Prohibited. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, LXIV (1). pp. 31-56. ISSN 1933-1592 White Rose Research Online [email protected] On Obscenity: The Thrill and Repulsion of the Morally Prohibited Matthew Kieran, University of Leeds Abstract The paper proceeds by criticising the central accounts of obscenity proffered by Feinberg, Scruton and the suggestive remarks of Nussbaum and goes on to argue for the following formal characterization of obscenity: x is appropriately judged obscene if and only if either A/ x is appropriately classified as a member of a form or class of objects whose authorized purpose is to solicit and commend to us cognitive-affective responses which are (1) internalized as morally prohibited and (2) does so in ways found to be or which are held to warrant repulsion and (3) does so in order to a/ indulge first order desires held to be morally prohibited or b/ indulge the desire to be morally transgressive or the desire to feel repulsed or c/ afford cognitive rewards or d/ any combination thereof or B/ x successfully elicits cognitive-affective responses which conform to conditions (1)- (3). I: Introduction What is it for something to be obscene? The question is both interesting philosophically and of practical import. -

The Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Emotional Labor and Its Effect on Job Burnout in Korean Organizations

The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Emotional Labor and Its Effect on Job Burnout in Korean Organizations A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Hyuneung Lee IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Gary N. McLean, Adviser February, 2010 © 2010 Hyuneung Lee i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe gratitude to all those people who have made this dissertation possible. First, I cannot express sufficient appreciation to my adviser, Dr. Gary N. McLean. I am so fortunate to have such a passionate and exemplary adviser. His patience and support enabled me to overcome the challenges I encountered during my entire journey as a doctoral student. He has read my dissertation literally word by word and provided insightful and invaluable feedback that I would not have been able to receive from anyone else. I have truly learned from him how to live as a scholar, a teacher, and a father. To me, he is the embodiment of the spirit of human resource development. I would also like to thank my committee members: Dr. John Campbell, Dr. Rosemarie Park, and Dr. Kenneth Bartlett. By raising issues from various perspectives, they have led me to see the big picture and take this dissertation to the next level. I will never forget their guidance and encouragement at every step. I also thank Dr. Seong-ik Park, my MA adviser in Seoul National University, for building my foundation as a researcher and teaching me how to write a dissertation. I must also mention Dr. -

Emotional Labor and Leadership: a Threat to Authenticity? ¬リニ¬リニ¬リニ

The Leadership Quarterly 20 (2009) 466–482 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect The Leadership Quarterly journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/leaqua Emotional labor and leadership: A threat to authenticity?☆,☆☆ William L. Gardner ⁎, Dawn Fischer 1, James G. (Jerry) Hunt 2 Texas Tech University, Rawls College of Business, 15th & Flint, Lubbock, TX 79409, United States article info abstract Keywords: Building on the emotional labor and authentic leadership literatures, we advance a conceptual Authentic leadership model of leader emotional displays. Three categories of leader emotional displays are Emotional labor identified: surface acting, deep acting and genuine emotions. The consistency of expressed Trust leader emotions with affective display rules, together with the type of display chosen, combines Well-being to impact the leader's felt authenticity, the favorability of follower impressions, and the Context perceived authenticity of the leader by the followers. Emotional intelligence, self-monitoring ability, and political skill are proposed as individual differences that moderate leader emotional display responses to affective events. We also look at followers' trust in the leader and leader well-being as key outcomes. Finally, we explore the influence on leader emotional labor of contextual dimensions of the environment, including the omnibus (national and organizational culture, industry and occupation, organizational structure, time) and discrete (situational) context. Directions for future research are discussed. © 2009 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. I try, to the extent possible, to maintain a level of calmness in the face of frantic issues. I try to be as objective as possible in discussions, and if I'm in a face-to-face meeting with someone who has a short fuse, I'll sit right next to that person to make sure the fuse is never lit. -

Alleviating the Burden of Emotional Labor: the Role of Social Sharing

Journal of Management Vol. 39 No. 2, February 2013 392-415 DOI: 10.1177/0149206310383909 © The Author(s) 2010 Reprints and permission: http://www. sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Alleviating the Burden of Emotional Labor: The Role of Social Sharing A. Silke McCance Procter & Gamble Christopher D. Nye University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Lu Wang University of New South Wales Kisha S. Jones University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Chi-yue Chiu Nanyang Technological University Difficult customer interactions cause service employees to experience negative emotions and to engage in emotional labor. The present laboratory study examined whether social sharing (i.e., talking about an emotionally arousing work event with one’s coworkers) can attenuate the residual anger lingering after a taxing service episode. Participants assumed the role of cus- tomer service representatives for a fictitious technical support hotline and encountered either neutral or difficult service interactions. After fielding three easy or three difficult calls, partici- pants were given the opportunity to engage in social sharing by talking about (a) the facts that just transpired, (b) the feelings aroused by the encounters, or (c) the positive aspects of the experience, or they were asked to complete a filler task. Results from quantitative data revealed Acknowledgments: This article was accepted under the editorship of Talya N. Bauer. We would like to thank Julie Jing Chen, Katie Reidy, Matthew Collison, Jason Schilli, Christopher Putnam, Clay Bishop, Lauren Carney, Deborah Rupp, and all our undergraduate research assistants for their assistance with various aspects of this study. Portions of this article were presented at the 23rd annual meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, San Francisco, California. -

In Love with a Stripper

CHAPTER 10 IN LOVE WITH A STRIPPER Young Girls as Preys in a Predator Society Encouraging five- to ten-year-old children to model themselves after sex workers suggests the degree to which matters of ethics and propriety have been decoupled from the world of marketing and advertising, even when the target audience is young children. The representational politics at work … connect children’s bodies to a reductive notion of sexuality, pleasure and commodification, while depicting children’s sexuality and bodies as nothing more than objects for voyeuristic adult consumption and crude financial profit. —Henry Giroux, Youth in a Suspect Society1 In late 2009, a toy company began selling a female doll which, as main feature, twirled around a plastic stripper poll. “The doll begins dancing when the music is turned on,” a blogger described, “and she goes ‘up and down’ and ‘round and round’.” On the box cover ran the following: “Style.” “Interesting.” “Music.” “Flash.” “Up and Down.” “Go Round and Round.” The targeted demographic: kids unskilled to decipher this insidious suggestion, of the stripper lifestyle as fun and chic—the thing to be. Gone are the days when society’s young girls are encouraged to emulate educa- tors, pioneers, lawyers, doctors, social workers, architects, activists, artists, or cultural critics. Today, the energy-expunging, dignity-diminishing exercise of stripping— all to temper the carnal demands of lustful men—is the new it. But selling spiritual death to children marks nothing new. For years now, corporations, in frenzy to enlarge coffers, have found children (and more so young girls) most vulnerable and lucrative.