Impact Matrix Analysis and Cost-Benefit Calculations to Improve Management Practices Regarding Health Status in Organic Dairy Farming (IMPRO)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homeopathy the Undiluted Facts Including a Comprehensive A–Z Lexicon Homeopathy the Undiluted Facts Edzard Ernst

Homeopathy The Undiluted Facts Including a Comprehensive A–Z Lexicon Homeopathy The Undiluted Facts Edzard Ernst Homeopathy The Undiluted Facts Including a Comprehensive A-Z Lexicon 123 Edzard Ernst Orford UK ISBN 978-3-319-43590-9 ISBN 978-3-319-43592-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-43592-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016947397 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Printed on acid-free paper This Springer imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Springer International Publishing AG Switzerland TO DANIELLE Foreword Since you are reading this foreword, I assume you have some interest in home- opathy. -

Australian Report

Celebrating 175 years The Faculty of Homeopathy Newsletter November 2019 Public pressure forces the publication of the ‘hidden’ Australian report ampaigners have succeeded Interestingly, she went on to issue a in forcing Australia’s leading clarification in relation to the second Cresearch organisation to publish review, stating that it “did not conclude a report on homeopathy that it had that homeopathy was ineffective”. This tried to suppress. Its publication has been raises the question as to why the NHMRC hailed as “a major win for transparency did not try to correct the damning and public accountability in research”. reports to the contrary that appeared The 300-page draft report was in the media and repeated by anti- the result of a study conducted in homeopathy campaigners. 2012 into the clinical effectiveness of Rachel Roberts, HRI chief homeopathy by Australia’s National executive, said: “For over three years Health and Medical Research Council the NHMRC have refused to release (NHMRC), but the research body their 2012 draft report on homeopathy, decided not to make its findings Rachel Roberts, HRI chief executive despite Freedom of Information public. Instead, it commissioned requests and even requests by members a second review that concluded campaign calling on the NHMRC to of the Australian Senate. To see this homeopathy had no therapeutic value publish the first report, which resulted document finally seeing the light of beyond placebo. On publication in in tens of thousands of people signing day is a major win for transparency 2015, the review’s findings were widely an online petition and questions being and public accountability in research.” reported in the media as the definitive asked in the Australian Senate. -

A Day in the Life

NEWS FEATURE A day in the life Landmark conference ‘New Horizons in Water Science: Evidence for Homeopathy?’ (with apologies to J Lennon & P McCartney) by Lionel Milgrom PhD MARH RHom and Dana Ullman MPH CCH Foreword Some people not only have good ideas, but are also prepared to work hard to bring those ideas into fruition. Ken (or Lord Aaron Kenneth Ward Atherton, to give him his proper title) is one such person. He decided that we all needed a strong antidote to the ‘no evidence’ claims so frequently vaunted by the anti-homeopathy campaigners, and he organised a truly unforgettable one-day event (held at the Royal Society of Medicine, London), to remind us that Lionel (LRM) has been a homeopath for ‘proper’ science can be fascinating, inspiring and truly uplifting. over 20 years, training at the now defunct Ken’s impressive line-up of presenters were all internationally re- London College of Homeopathy, and the nowned scientists, including two Nobel laureates, and the theme Orion course in advanced homeopathy. He of the event was to explore the science underpinning our knowledge works from home now but has laboured of water structures. I came away from the day feeling really positive; at Nelsons, Ainsworths, and an integrated our emerging understanding of the science of water structures may dental practice in London’s West End. He is well lead us to eventually being able to explain how homeopathy also a scientist (chemist; co-founding an can work at a purely energetic level. On behalf of Team ARH and anticancer biotech spinout company), the rest of the homeopathy community, I would like to thank Ken a science writer, and in his latest incarna- for having the determination, perseverance and, above all, the vision tion, a chemistry teacher. -

Evidence Check 2: Homeopathy

House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Evidence Check 2: Homeopathy Fourth Report of Session 2009–10 HC 45 House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Evidence Check 2: Homeopathy Fourth Report of Session 2009–10 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 8 February 2010 HC 45 Published on 22 February 2010 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Science and Technology Committee The Science and Technology Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Government Office for Science. Under arrangements agreed by the House on 25 June 2009 the Science and Technology Committee was established on 1 October 2009 with the same membership and Chairman as the former Innovation, Universities, Science and Skills Committee and its proceedings were deemed to have been in respect of the Science and Technology Committee. Current membership Mr Phil Willis (Liberal Democrat, Harrogate and Knaresborough)(Chairman) Dr Roberta Blackman-Woods (Labour, City of Durham) Mr Tim Boswell (Conservative, Daventry) Mr Ian Cawsey (Labour, Brigg & Goole) Mrs Nadine Dorries (Conservative, Mid Bedfordshire) Dr Evan Harris (Liberal Democrat, Oxford West & Abingdon) Dr Brian Iddon (Labour, Bolton South East) Mr Gordon Marsden (Labour, Blackpool South) Dr Doug Naysmith (Labour, Bristol North West) Dr Bob Spink (Independent, Castle Point) Ian Stewart (Labour, Eccles) Graham Stringer (Labour, Manchester, Blackley) Dr Desmond Turner (Labour, Brighton Kemptown) Mr Rob Wilson (Conservative, Reading East) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental Select Committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No.152. -

HAHNEMANN LABORATORIES, INC. High Quality, High Potency

��������������������������������� �� ����������������������� ���������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������ ��������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������ �������������������������� ������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������� �� ���������������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������ ������������������������ ��������������������������������������������������� �� �������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������������������ -

All Royal Warrant-Holding Companies

ALL ROYAL WARRANT-HOLDING COMPANIES A.C. Bacon Engineering Ltd A.C. Cooper (Colour) Ltd A. Fulton Company Limited A. Hester Ltd A.J. Freezer Water Services Ltd A. Nash A.S. Handover Ltd A&E Fire and Security Limited Abaris Holdings Limited T/A Arthur Sanderson & Sons Abbey England Limited Abels Moving Service T/A Abels Adexchange Media Limited ADM Agriculture Ltd Agma Ltd Agri-Cycle Ainsworths Homoeopathic Pharmacy Airglaze Aviation GmbH A J Charlton & Sons Ltd Alan Scott Panel Beater & Paint Sprayer Albert Amor Ltd Albert E. Chapman Ltd Alexandre of England 1988 Ltd All About Baths Allan Coggin Furnishing Consultant Allen & Foxworthy Ltd Allen & Page Ltd April 2020 Allens Farm Amber Computing & IT Services Ltd Amenity Horticulture Services Amerex Fire International Ltd Anderson & Sheppard Ltd Andrew M. Jarvis Ltd. T/A Sandringham Apple Juice Andrew Wilson & Sons Ltd Andy Spooner Painters And Decorators Anglia IT Solutions Ltd Angostura Ltd Angus Chain Saw Service Anthony A. Barker Ltd T/A Barker Group Anthony Buckley & Constantine Ltd Apex Lift & Escalator Engineers Ltd Apollo Fire Detectors Limited Aquadition Ltd Arcan Services Ardayre Interiors Armitage Pet Products Limited Arnold Wiggins & Sons Ltd Arnott & Mason (Horticulture) Ltd Arterial Moving Ltd Artistic Iron Products Ltd ASD Limited T/A Kloeckner Metals UK Asprey London Limited Aston Martin Lagonda Ltd Aubrey Allen Ltd Autoglym Ltd Autoscan Ltd A W Hainsworth and Sons Limited Axflow Ltd Axminster Carpets Limited Bacardi-Martini Ltd April 2020 Baco-Compak (Norfolk) Ltd Badgemaster Ltd Balgownie Ltd Ballyclare Limited Banchory Dry Cleaners Barber Wilsons & Co Ltd Barcham Trees Plc Barnard & Westwood Ltd BBA Shipping & Transport Ltd. -

'Evidence Check 2: Homeopathy' Report

House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Evidence Check 2: Homeopathy Fourth Report of Session 2009–10 EMBARGOED ADVANCE COPY Not to be published in full, or in part, in any form before 11.00 on Monday 22 February 2010 HC 45 House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Evidence Check 2: Homeopathy Fourth Report of Session 2009–10 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 8 February 2010 EMBARGOED ADVANCE COPY Not to be published in full, or in part, in any form before 11.00 on Monday 22 February 2010 HC 45 Published on 22 February 2010 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Science and Technology Committee The Science and Technology Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Government Office for Science. Under arrangements agreed by the House on 25 June 2009 the Science and Technology Committee was established on 1 October 2009 with the same membership and Chairman as the former Innovation, Universities, Science and Skills Committee and its proceedings were deemed to have been in respect of the Science and Technology Committee. Current membership Mr Phil Willis (Liberal Democrat, Harrogate and Knaresborough)(Chairman) Dr Roberta Blackman-Woods (Labour, City of Durham) Mr Tim Boswell (Conservative, Daventry) Mr Ian Cawsey (Labour, Brigg & Goole) Mrs Nadine Dorries (Conservative, Mid Bedfordshire) Dr Evan Harris (Liberal Democrat, Oxford West & Abingdon) Dr Brian Iddon (Labour, Bolton South East) Mr Gordon Marsden (Labour, Blackpool South) Dr Doug Naysmith (Labour, Bristol North West) Dr Bob Spink (Independent, Castle Point) Ian Stewart (Labour, Eccles) Graham Stringer (Labour, Manchester, Blackley) Dr Desmond Turner (Labour, Brighton Kemptown) Mr Rob Wilson (Conservative, Reading East) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental Select Committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No.152. -

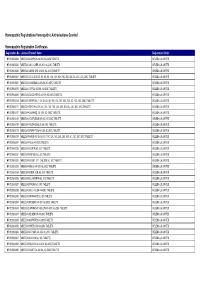

HR & NR Listing with Product Name (FINAL) 18-05-2021

Homeopathic Registrations/Homeopathic Authorisations Granted Homeopathic Registration Certificates Registration No. Licensed Product Name Registration Holder HR 00298/0006 WELEDA ACID PHOS 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0020 WELEDA CALC. CARB. 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0033 WELEDA CARBO VEG 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0047 WELEDA COCCULUS 4X, 5X, 6X, 8X, 10X, 12X, 15X, 20X, 25X, 30X, 6C, 12C, 30C, 200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0061 WELEDA CHAMOMILLA 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0075 WELEDA COFFEA 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0089 WELEDA COLOCYNTHIS 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0103 WELEDA HEPAR SULF. 4X, 5X, 6X, 8X, 10X, 15X, 20X, 25X, 30X, 6C, 12C, 30C, 200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0117 WELEDA IGNATIA 4X, 5X, 8X, 10X, 12X, 15X, 20X, 25X, 30X, 6C, 12C, 30C, 200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0131 WELEDA KALI PHOS. 4X- 30X, 6C- 200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0145 WELEDA LYCOPODIUM 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0159 WELEDA PHOSPHOROUS 4X-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0173 WELEDA SYMPHYTUM 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0187 WELEDA TAMUS 4X, 5X, 6X, 8X, 10X, 12X, 15X, 20X, 25X, 30X, 6C, 12C, 30C, 200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0201 WELEDA THUJA 4X-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0228 WELEDA ACONITE 6C, 30C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0231 WELEDA APIS MEL 6C, 30C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0232 WELEDA ARGENT. -

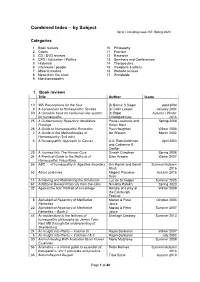

Combined Index – by Subject up to / Including Issue #67, Spring 2020

Combined Index – by Subject Up to / including issue #67, Spring 2020 Categories 1 Book reviews 10 Philosophy 2 Cases 11 Practice 3 CD / DVD reviews 12 Research 4 CPD / Education / Politics 13 Seminars and Conferences 5 Historical 14 Therapeutics 6 Interviews / people 15 Viewpoint & letters 7 Materia medica 16 Website reviews 8 News from the Chair 17 Worldwide 9 Non-homeopathy 1. Book reviews Title Author Issue 10 365 Prescriptions for the Soul Dr Bernie S Siegel April 2004 9 A Companion to Homeopathic Studies Dr Colin Lessell January 2004 50 A complete book on cardiovascular system Dr Rajat Autumn / Winter for homeopaths Chattopadhyay 2014 25 A Contemporary Repertory: Meditative Paula Leszczuk and Spring 2008 Provings Karen Main 28 A Guide to Homoeopathic Remedies Paul Houghton Winter 2008 2 A Guide to the Methodologies of lan Watson March 2002 Homoeopathy (2nd edn) 6 A Homeopathic Approach to Cancer A.U. Ramakrishnan April 2003 and Catherine R. Coulter 25 A Journey Into The Human Core Dinesh Chauhan Spring 2008 24 A Practical Guide to the Methods of Ellen Kramer Winter 2007 Homeopathic Prescribing 56 ABC … of homeopathy in digestive disorders Drs Ronak and Sonal Summer/Autumn Shah 2016 53 About potencies Magriet Plouview- Autumn 2015 Suijs 14 Achieving and Maintaining the Similimum Luc de Schepper Summer 2005 67 Additional Banerji Protocols from the Clinic Nimisha Parekh Spring 2020 32 Against the tide: Portrait of a marriage Review of a play at Winter 2009 the Edinburgh Festival 8 Alphabetical Repertory of Meditative Marion & Peter October -

Library of Julian Winston • Tawa, New Zealand

library of Julian Winston • tawa, New Zealand 1 A Small Guide to the Principles of Homoeopathic Prescribing domestic medicine A Small Guide to the Principles of Homoeopathic Prescribing inscribed by: editor/trans.: size: 12mo pages: 23 edition: publisher: A. Nelson and Co. condition/ comments reference: binding:pamphlet good. est. value: 5 language illustrations: Directory of Homoeopathic Physicians directory Directory of Homoeopathic Physicians in United States and Canada inscribed by: editor/trans.: size: 8vo pages: 233 edition: 1st publisher: American Institute of Homeopathy Chicago, IL condition/ comments reference: binding:soft poor. cover torn and fragile. est. value: no date, introduction says this is "the first attempt". THe Second edition had ads with date of 1921. 15 language illustrations: Directory of the ABHT directory Directory of the American Board of Homeotherapeutics inscribed by: editor/trans.: size: 12mo pages: 25 edition: publisher: ABHT ? Alexandria VA condition/ comments reference: binding:soft new est. value: 10 language illustrations: A Collection of Interesting Books catalog A Collection of Interesting and Valuable Books and Pamphlets, Antiquarian and Modern, from the Libraries of Constane Hering (deceased) and Dr. Calvin B. Knerr inscribed by: editor/trans.: size: 4to pages: np edition: publisher: Calvin B. Knerr nd Philadelphia condition/ comments reference: binding:loose fair. est. value: List of library for sale. Photos of Knerr and Hering. In English and German. circa 1935. 150 language illustrations: library of Julian Winston • tawa, New Zealand 2 Carcinosin materia medica Carcinosin: a composite picture from british homeopaths inscribed by: editor/trans.: size: 4to pages: 12 edition: publisher: private nd condition/ comments reference: binding:pamphlet New est. -

Promoting Integrated Healthcare

The Faculty of Homeopathy Newsletter May 2020 Promoting integrated healthcare he Faculty of Homeopathy has knowledge and understanding Dr Gary Smyth become a founding member of complementary, traditional and Tof the Integrated Healthcare natural healthcare Collaborative (IHC), which is a • encourage whole-person, collection of leading organisations individualised healthcare within complementary, traditional • raise issues in integrated and natural healthcare. healthcare with government and The IHC was formed following decision makers a recommendation in a report by • develop co-ordinated strategies the former All-Party Parliamentary to help patients access accurate Group for Integrated Healthcare information on integrated entitled Integrated Healthcare: healthcare putting the pieces together. It said that • support the development of a “professional associations representing robust and appropriate evidence complementary, traditional and base natural healthcare should work more • facilitate better access to, and closely together on common issues, choice of, appropriate to share knowledge and experience. complementary, traditional and A formal collaborative should be natural healthcare within the NHS established which brings together • advocate collaboration with major associations to take the field conventional Western healthcare forward collectively.” professionals. Shared belief Commitment IHC members believe that an Faculty president Dr Gary Smyth integrated healthcare service would said: “As a member of the IHC the improve patient experience, bring Faculty is showing its commitment about better patient outcomes, and provide a framework for a more to working collectively with other cost-effective delivery of healthcare key organisations to increase access services. to homeopathy and other therapies, Their shared belief is also outlined promote greater integration with collaboration between the former in the parliamentary report. -

Homeopathic Prevention and Treatment of Epidemics & Pandemics

Homeopathic Prevention & Treatment of Epidemics & Pandemics Sharum Sharif, ND American Association of Naturopathic Physicians August of 2019, Portland, Oregon Cholera, a Horrific Present-Day Epidemic • Cholera killed 1.1 million people in Yemen in just 2017 alone. • How BIG is 1.1 million? That’s approximately the population of the following cities in WA: Seattle(725K), Bellevue(144K), Renton(101K), kirkland(88K), & Redmond(64K) • 1.1m in one year = 3090 people PER DAY! (Note: Malaria also kills 3000 children/day.) • The national average public school student size is approximately 525 students (2018-19). So, 1.1 million in one year = 3090/day = number of Kids in 6 U.S. publiC schools/day. Why should we discuss epidemics and why should we prepare ourselves for them ? •Epidemics are on the rise, and they will be one of the main challenges we will face as a species increasingly over the next few years and in the future. •The biggest killers in history have been epidemic diseases. And, that is why we should prepare ourselves for them. What are epidemic & pandemic diseases? • EndemiC: Regularly found among particular people or in a certain area, and it goes on through generations. Example: • Cholera has been endemic in India for 2000 years. • Plague is endemic in the Western U.S., South America, Asia and Africa. • EpidemiC: Much more acute than endemic. A widespread occurrence of an infectious disease in a community at a particular time. • PandemiC: Prevalent over a whole country or the world. What sort of epidemics are we referring to here? True epidemics are acute infectious diseases.