Managing Saskatchewan Wetlands ~ a Landowner's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bioadvantage Trials Program the Leading Pea 2 Tagteam Bioniq VS

2020 BIOADVANTAGE HARVEST TRIALS DATA inoculant on pea Results - pea Over the past 6 years, e orts from producers, retails, Table of contents and agronomists like you have contributed to making the BioAdvantage Trials program the leading Pea 2 TagTeam BioniQ VS. Competitors Average Yield inoculant fi eld scale testing program in the industry. TagTeam Yield Competitor Location Year BioniQ Di erence TagTeam BioniQ 2 (bu/ac) The successful development and testing of inoculant Yield (bu/ac) (bu/ac) All competitors products has contributed to a deeper understanding TagTeam LCO 3 Forestburg, AB 2019 48.0 46.0 2.0 49.3 (bu/ac) of the agronomics, placement, and expectations Innisfail, AB 2020 71.4 68.5 2.8 of the portfolio. Lentil 4 Magrath, AB 2019 34.2 35.0 -0.8 Peas TagTeam BioniQ Munson, AB 2018 29.3 27.3 2.0 52.8 (bu/ac) As a result of your commitment to the program, TagTeam BioniQ 4 Oyen, AB 2018 53.3 54.2 -0.9 over 400 trials – across 6 provinces, with Oyen, AB 2020 34.0 35.7 -1.7 TagTeam LCO 5 Cabri, SK 2019 52.6 48.7 3.9 6 di erent inoculants on 12 di erent crops Source: Results were collected from 26 farmer-conducted, large- have been completed. Canwood, SK 2018 55.1 43.2 11.9 scale, side-by-side BioAdvantage Trials conducted in Alberta and Saskatchewan from 2017-2020. Barley 6 Govan, SK 2018 42.2 41.0 1.2 Thank you for your continued support, and Govan, SK 2018 42.2 40.7 1.5 we look forward to collaborating on future BioniQ 6 Kinley, SK 2018 66.9 63.6 3.3 BioAdvantage Trials to test the inoculant Leross, SK 2019 58.8 49.6 9.2 Wheat 7 and micronutrient products from McLean, SK 2019 43.6 38.5 5.1 the expanded NexusBioAg portfolio. -

Diabetes Directory

Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory February 2015 A Directory of Diabetes Services and Contacts in Saskatchewan This Directory will help health care providers and the general public find diabetes contacts in each health region as well as in First Nations communities. The information in the Directory will be of value to new or long-term Saskatchewan residents who need to find out about diabetes services and resources, or health care providers looking for contact information for a client or for themselves. If you find information in the directory that needs to be corrected or edited, contact: Primary Health Services Branch Phone: (306) 787-0889 Fax : (306) 787-0890 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Saskatchewan Ministry of Health acknowledges the efforts/work/contribution of the Saskatoon Health Region staff in compiling the Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory. www.saskatchewan.ca/live/health-and-healthy-living/health-topics-awareness-and- prevention/diseases-and-disorders/diabetes Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................... - 1 - SASKATCHEWAN HEALTH REGIONS MAP ............................................. - 3 - WHAT HEALTH REGION IS YOUR COMMUNITY IN? ................................................................................... - 3 - ATHABASCA HEALTH AUTHORITY ....................................................... - 4 - MAP ............................................................................................................................................... -

Saskatchewan Conference Prayer Cycle

July 2 September 10 Carnduff Alida TV Saskatoon: Grace Westminster RB The Faith Formation Network hopes that Clavet RB Grenfell TV congregations and individuals will use this Coteau Hills (Beechy, Birsay, Gull Lake: Knox CH prayer cycle as a way to connect with other Lucky Lake) PP Regina: Heritage WA pastoral charges and ministries by including July 9 Ituna: Lakeside GS them in our weekly thoughts and prayers. Colleston, Steep Creek TA September 17 Craik (Craik, Holdfast, Penzance) WA Your local care facilities Take note of when your own pastoral July 16 Saskatoon: Grosvenor Park RB charge or ministry is included and remem- Colonsay RB Hudson Bay Larger Parish ber on that day the many others who are Crossroads (Govan, Semans, (Hudson Bay, Prairie River) TA holding you in their prayers. Raymore) GS Indian Head: St. Andrew’s TV Saskatchewan Crystal Springs TA Kamsack: Westminister GS This prayer cycle begins a week after July 23 September 24 Thanksgiving this year and ends the week Conference Spiritual Care Educator, Humboldt (Brithdir, Humboldt) RB of Thanksgiving in 2017. St. Paul’s Hospital RB Kelliher: St. Paul GS Prayer Cycle Crossroads United (Maryfield, Kennedy (Kennedy, Langbank) TV Every Pastoral Charge and Special Ministry Wawota) TV Kerrobert PP in Saskatchewan Conference has been 2016—2017 Cut Knife PP October 1 listed once in this one year prayer cycle. Davidson-Girvin RB Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Sponsored by July 30 Imperial RB The Saskatchewan Conference Delisle—Vanscoy RB KeLRose GS Eatonia-Mantario PP Kindersley: St. Paul’s PP Faith Formation Network Earl Grey WA October 8 Edgeley GS Kinistino TA August 6 Kipling TV Dundurn, Hanley RB Saskatoon: Knox RB Regina: Eastside WA Regina: Knox Metropolitan WA Esterhazy: St. -

Bylaw No. 3 – 08

BYLAW NO. 3 – 08 A bylaw of The Urban Municipal Administrators’ Association of Saskatchewan to amend Bylaw No. 1-00 which provides authority for the operation of the Association under the authority of The Urban Municipal Administrators Act. The Association in open meeting at its Annual Convention enacts as follows: 1) Article V. Divisions Section 22 is amended to read as follows: Subsection (a) DIVISION ONE(1) Cities: Estevan, Moose Jaw, Regina and Weyburn Towns: Alameda, Arcola, Assiniboia, Balgonie, Bengough, Bienfait, Broadview, Carlyle, Carnduff, Coronach, Fleming, Francis, Grenfell, Indian Head, Kipling, Lampman, Midale, Milestone, Moosomin, Ogema, Oxbow, Pilot Butte, Qu’Appelle, Radville, Redvers, Rocanville, Rockglen, Rouleau, Sintaluta, Stoughton, Wapella, Wawota, White City, Whitewood, Willow Bunch, Wolseley, Yellow Grass. Villages: Alida, Antler, Avonlea, Belle Plaine, Briercrest, Carievale, Ceylon, Creelman, Drinkwater, Fairlight, Fillmore, Forget, Frobisher, Gainsborough, Gladmar, Glenavon, Glen Ewen, Goodwater, Grand Coulee, Halbrite, Heward, Kendal, Kennedy, Kenosee Lake, Kisbey, Lake Alma, Lang, McLean, McTaggart, Macoun, Manor, Maryfield, Minton, Montmarte, North Portal, Odessa, Osage, Pangman, Pense, Roch Percee, Sedley, South Lake, Storthoaks, Sun Valley, Torquay, Tribune, Vibank, Welwyn, Wilcox, Windthorst. DIVISION TWO(2) Cities: Swift Current Towns: Burstall, Cabri, Eastend, Gravelbourg, Gull Lake, Herbert, Kyle, Lafleche, Leader, Maple Creek, Morse, Mossbank, Ponteix, Shaunavon. Villages: Abbey, Aneroid, Bracken, -

Part I/Partie I

THIS ISSUE HAS NO PART II (REVISED REGULATIONS) or PART III (REGULATIONS)/ THE SASKATCHEWAN GAZETTE, MAY 6, 2011 1081 CE NUMÉRO NE CONTIENT PAS DE PARTIE II (RÈGLEMENTS RÉVISÉS) OU DE PARTIE III (RÈGLEMENTS) The Saskatchewan Gazette PUBLISHED WEEKLY BY AUTHORITY OF THE QUEEN’S PRINTER/PUBLIÉE CHAQUE SEMAINE SOUS L’AUTORITÉ DE L’IMPRIMEUR DE LA REINE PART I/PARTIE I Volume 107 REGINA, FRIDAY, MAY 6, 2011/REGINA, VENDREDI, 6 MAI 2011 No. 18/nº 18 TABLE OF CONTENTS/TABLE DES MATIÈRES PART I/PARTIE I SPECIAL DAY/JOUR SPÉCIAUX ...................................................................................................................................................... 1082 APPOINTMENTS/NOMINATIONS ................................................................................................................................................... 1082 PROGRESS OF BILLS/RAPPORT SUR L’ÉTAT DES PROJETS DE LOI (Fourth Session, Twenty-sixth Legislative Assembly/Quatrième session, 26e Assemblée législative) ............................................ 1083 ACTS NOT YET PROCLAIMED/LOIS NON ENCORE PROCLAMÉES ..................................................................................... 1084 ACTS IN FORCE ON ASSENT/LOIS ENTRANT EN VIGUEUR SUR SANCTION (Fourth Session, Twenty-sixth Legislative Assembly/Quatrième session, 26e Assemblée législative) ............................................ 1087 ACTS IN FORCE ON SPECIFIC EVENTS/LOIS ENTRANT EN VIGUEUR À DES OCCURRENCES PARTICULIÈRES..... 1087 ACTS PROCLAIMED/LOIS PROCLAMÉES (2011) ....................................................................................................................... -

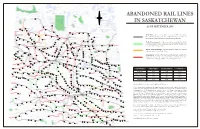

Abandoned Rail Lines in Saskatchewan

N ABANDONED RAIL LINES W E Meadow Lake IN SASKATCHEWAN S Big River Chitek Lake AS OF SEPTEMBER 2008 Frenchman Butte St. Walburg Leoville Paradise Hill Spruce Lake Debden Paddockwood Smeaton Choiceland Turtleford White Fox LLYODMINISTER Mervin Glaslyn Spiritwood Meath Park Canwood Nipawin In-Service: rail line that is still in service with a Class 1 or short- Shell Lake Medstead Marshall PRINCE ALBERT line railroad company, and for which no notice of intent to Edam Carrot River Lashburn discontinue has been entered on the railroad’s 3-year plan. Rabbit Lake Shellbrooke Maidstone Vawn Aylsham Lone Rock Parkside Gronlid Arborfield Paynton Ridgedale Meota Leask Zenon Park Macdowell Weldon To Be Discontinued: rail line currently in-service but for which Prince Birch Hills Neilburg Delmas Marcelin Hagen a notice of intent to discontinue has been entered in the railroad’s St. Louis Prairie River Erwood Star City NORTH BATTLEFORD Hoey Crooked River Hudson Bay current published 3-year plan. Krydor Blaine Lake Duck Lake Tisdale Domremy Crystal Springs MELFORT Cutknife Battleford Tway Bjorkdale Rockhaven Hafford Yellow Creek Speers Laird Sylvania Richard Pathlow Clemenceau Denholm Rosthern Recent Discontinuance: rail line which has been discontinued Rudell Wakaw St. Brieux Waldheim Porcupine Plain Maymont Pleasantdale Weekes within the past 3 years (2006 - 2008). Senlac St. Benedict Adanac Hepburn Hague Unity Radisson Cudworth Lac Vert Evesham Wilkie Middle Lake Macklin Neuanlage Archerwill Borden Naicam Cando Pilger Scott Lake Lenore Abandoned: rail line which has been discontinued / abandoned Primate Osler Reward Dalmeny Prud’homme Denzil Langham Spalding longer than 3 years ago. Note that in some cases the lines were Arelee Warman Vonda Bruno Rose Valley Salvador Usherville Landis Humbolt abandoned decades ago; rail beds may no longer be intact. -

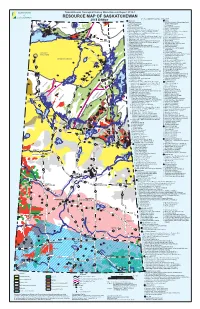

Mineral Resource Map of Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan Geological Survey Miscellaneous Report 2018-1 RESOURCE MAP OF SASKATCHEWAN KEY TO NUMBERED MINERAL DEPOSITS† 2018 Edition # URANIUM # GOLD NOLAN # # 1. Laird Island prospect 1. Box mine (closed), Athona deposit and Tazin Lake 1 Scott 4 2. Nesbitt Lake prospect Frontier Adit prospect # 2 Lake 3. 2. ELA prospect TALTSON 1 # Arty Lake deposit 2# 4. Pitch-ore mine (closed) 3. Pine Channel prospects # #3 3 TRAIN ZEMLAK 1 7 6 # DODGE ENNADAI 5. Beta Gamma mine (closed) 4. Nirdac Creek prospect 5# # #2 4# # # 8 4# 6. Eldorado HAB mine (closed) and Baska prospect 5. Ithingo Lake deposit # # # 9 BEAVERLODGE 7. 6. Twin Zone and Wedge Lake deposits URANIUM 11 # # # 6 Eldorado Eagle mine (closed) and ABC deposit CITY 13 #19# 8. National Explorations and Eldorado Dubyna mines 7. Golden Heart deposit # 15# 12 ### # 5 22 18 16 # TANTATO # (closed) and Strike deposit 8. EP and Komis mines (closed) 14 1 20 #23 # 10 1 4# 24 # 9. Eldorado Verna, Ace-Fay, Nesbitt Labine (Eagle-Ace) 9. Corner Lake deposit 2 # 5 26 # 10. Tower East and Memorial deposits 17 # ###3 # 25 and Beaverlodge mines and Bolger open pit (closed) Lake Athabasca 21 3 2 10. Martin Lake mine (closed) 11. Birch Crossing deposits Fond du Lac # Black STONY Lake 11. Rix-Athabasca, Smitty, Leonard, Cinch and Cayzor 12. Jojay deposit RAPIDS MUDJATIK Athabasca mines (closed); St. Michael prospect 13. Star Lake mine (closed) # 27 53 12. Lorado mine (closed) 14. Jolu and Decade mines (closed) 13. Black Bay/Murmac Bay mine (closed) 15. Jasper mine (closed) Fond du Lac River 14. -

Saskatchewan Provincial Electoral Constituency Provincial: Composite

Saskatchewan Provincial 110°W 109 °W 108°W 102°W Electoral 107°W 106°W 105°W 104°W 103°W Constituency CAMS ELL PORTAGE URANIUM CITY Provincial: Composite STO N Y RA PID S UV905 0 25 50 75 59°N 59°N Kilometres Creation Date 02/02/2015 Version 1.0 ² The new 61 Saskatchewan provincial constituencies will come into effect with the dissolution of the 27th Legislative Assembly, just prior to the next general election that is scheduled for November 2, 2015. Saskatchewan constituency boundaries are drawn in accordance UV955 with The Representation Act, 2002 and any amendments thereto. These maps have been produced solely for the purpose of identifying polling divisions within each constituency for the 28th general election. Data Source: Information Services Corporation WOLLASTON 58°N LAKE Map 1 of 1 58°N UV905 ATHABASCA DESCHARME LAKE 57°N UV955 57°N CUMBERLAND UV955 LA LOCHE TUR N O R UV914 LAK E UV905 BLACK POINT GA RSON 909 BEAR UV LAKE CREEK UV956 UV102 SOUTHEND UV155 BRABA NT M ICH E L 56°N VILLA G E UV102 56°N ST. BUFFA LO GE O R GE ' S NARROW HILL S PATU AN A K UV914 UV925 UV155 UV102 M ISS INIP E UV908 ILE-A-LA-CROSSE PINEHOUSE SANDY BAY UV903 STANLEY MIS SION UV135 UV918 UV915 UV165 UV910 102 UV PELICAN B EAUVAL NARROWS JA N S B AY UV165 935 AIR UV LA RONGE 55°N RONGE UV135 UV2 55°N UV165 UV106 911 UV FLIN FLON CREIGHTON UV919 UV165 UV903 DENARE BE ACH UV106 UV912 DO R E LAK E UV924 UV2 UV969 UV167 UV916 GR E IG LAK E UV155 21 SO U TH UV GO WA ODSOIL TE R HE N PIE RCELA ND LAK E SLED 55 LAKE WE YAK WIN UV DORINTOSH 106 UV924 927 UV GREEN UV UV26 UV4 LAKE UV55 UV55 ME 922 ADOW UV TIM BE R LAKE BAY LOON 55 2 920 UV UV 913 UV LAKE UV UV912 54°N UV304 UV942 UV926 MAKWA 54°N MEADOW CUMBERLAND HOUS E UV943 NE SS LIN LAK E R 26 LITTLE UV P 265 123 H ILLIPS UV UV FIS H IN G LAKE GR O V E E 120 L UV AK E 943 UV 106 T UV BIG S CH ITE K UV945 LAK E RIVER N 263 CA ND LE I UV21 946 UV LAK E UV24 UV UV926 M O WE RY HO R SE SH O E ST. -

Saskatchewan Registered Dietitian Directory for Individual Client Services

Saskatchewan Registered Dietitian Directory for Individual Client Services There are multiple ways to access the individual services of a Registered Dietitian in Saskatchewan. How you access the Dietitian’s services will depend on where you live and what type of service you need. Use our directory to help navigate. It is organized alphabetically by regional health authority. Tribal councils are included under the heading of the closest regional health authorities. Private practice Dietitians are listed on the last page, alphabetically by the name of the private practice. 1. Self-refer! Phone your local health center or the number listed below and ask to speak to the dietitian. 2. Have your family physician or allied health care provider send a referral for dietitian services. 3. Contact a private practice Dietitian who offers fee for service. Check your insurance plan to see if you have coverage. Regional Heath Dietitian Contact Information ***Unless otherwise stated, the Authority/Organization Dietitian accepts self and allied health provider referral Provincial Resources Canadian Diabetes Association Phone: 306-933-1238 Ext. 2853 Health Canada (Canadian Prenatal Nutrition Program) Phone: 306-780-5791 Health Canada (Aboriginal Diabetes Initiatives) Phone:306-780-7246 Sports Medicine and Science Council of Saskatchewan Phone: 975-0849 Athabasca Health Phone: 306-439-2647 Authority Cypress Health Region Swift Current, Eastend, Gull Lake, Herbert, Hodgeville, Leader, Mankota, Maple Creek, Ponteix, Shaunavon, Vanguard Phone: 306-778-5118 or 1-877-401-8071 Five Hills Health Patient Education Center for all communities in Region the Five Hills Health Region Phone: 694-0230 Fax:694-0241 Heartland Health Kerrobert/Macklin/Unity/Wilkie- Region Phone: 306-228-4442 Ext. -

Powering Through The

THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE SASKATCHEWAN MINING ASSOCIATION POWERING THROUGH THE CYCLE TOP 10 CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES MINING COMPANIES INNOVATE FOR STRENGTH NORTHLANDS COLLEGE MINE SCHOOL TAKING EDUCATION TO HIGHER LEVELS SASKATCHEWAN EARNS AN A SPRING / SUMMER 2015 FRASER INSTITUTE GIVES PROVINCE Publication Mail Agreement No. 42154021 TOP MARKS IN CANADA ORE | THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE SASKATCHEWAN MINING ASSOCIATION FALL/WINTER 2013 ORE | THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE SASKATCHEWAN MINING ASSOCIATION SPRING/SUMMER 2015 wherever there’s mining, we’rE THERE. Tim Gitzel speaks with employees at Cigar Lake at a celebration of the first ore production. ORE is produced solely by the Saskatchewan Mining Association. CONTENTS HEAD OFFICE ® Suite 1500 COVER FEATURE GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE No other manufacturer can offer what Caterpillar does: 2002 Victoria Avenue Regina, Saskatchewan TOP 10 TOP PROVINCE TOPS IN S4P 0R7 The broadest line of surface and underground equipment in the industry. Challenges and Fraser Institute INNOVATION Telephone: (306) 757-9505 Fax: (306) 569-1085 opportunities after gives Saskatchewan What’s new in mining the supercycle high marks technology Wherever there is drilling and digging, loading and hauling, grading and dozing, you will find www.saskmining.ca Cat® machines hard at work. Cat products are on more mine sites than any other equipment line, CONTACT FOR ADVERTISERS 5 8 14 delivering the reliability and durability you need to mine efficiently and productively. Tap Communications Inc. 203-262 Avenue B South ORE DEPOSITS: SODIUM SULPHATE Saskatoon, Saskatchewan 3 S7M 1M4 Kramer Ltd. offers the finest people, service and tooling throughout our province-wide branch ENVIRONMENT Telephone: (306) 373-7330 Tailings facilities part of mine design 10 network to meet and exceed the demands of Saskatchewan’s growing mining industry. -

Lake Diefenbaker Tourism Destination Area Plan

Lake Diefenbaker Tourism Destination Area Plan Lake Diefenbaker Tourism Destination Area Plan “A tourism destination area is a geographic area in which attractions, businesses, residents and regulatory authorities work together to deliver distinctive, high quality services and experiences, capable of attracting and holding significant numbers of visitors, from both within and outside the province.” Lake Diefenbaker Tourism Destination Area Plan Letter of Transmittal July 16, 2008 Dr. Lynda Haverstock, President and Chief Executive Officer, Tourism Saskatchewan, 1922 Park Street, Regina, Saskatchewan Dear Dr. Haverstock: We are pleased to submit the Lake Diefenbaker Tourism Destination Area Plan. The plan identifies tourism development issues and opportunities, and recommends specific strategies and actions to deal with them. The Tourism Planning Committee included a number of local stakeholders and representatives of tourism associations. In addition, public meetings held at Riverhurst, Elbow, Davidson, Kyle, Demaine, Outlook, and the Whitecap Dakota First Nation gave residents an opportunity to provide input in developing the plan. We would appreciate you forwarding copies of the plan to the Ministry of Tourism, Parks, Culture, and Sport, the Ministry of the Environment, the Ministry of Highways and Infrastructure, the Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation, and the Ministry of Municipal Affairs. The plan includes recommendations that pertain to these Ministries. We appreciate the assistance provided by Tourism Saskatchewan throughout the planning process, and we look forward to implementation of the plan. Sincerely, The Lake Diefenbaker Tourism Destination Area Planning Committee I Lake Diefenbaker Tourism Destination Area Plan PLANNING COMMITTEE Jim Tucker Russ McPherson General Manager - Mid Sask CFDC/ER Project Manager – WaterWolf M.L. -

Planning for a Brighter G G Future: Municipalities Ki H Working Together

Planninggg for a Brighter Future: Municipalities Working Togeth er Presented byyy: Shelley Kilbride, Municipal Capacity Development Progg(ram (MCDP) Saskatchewan at a Glance Total population of 1,045,622 651, 900 square km– total area 296 rural and 464 urban and northern municipalities Increasing and Ageing Population Increasing Urbanization Extraordinary Development Increasing Social Demands Ageing Infrastructure Escalating Costs and changing Regulatory Requirements Sources: www.statcan.gc.ca / Monthly statistical review- http://www.stats.gov.sk.ca/stats/Sep10.pdf / Saskatchewan Stats Sheet – 2010 -http://www.stats.gov.sk.ca/Default.aspx?DN=b2e511d6-2c66-4f7d- 9461-69f4bffd3629 Current Local Capacity 625 administrators for over 790 municipalities 137 municipalities with under 100 in population 60% of all municipalities have zoning byy%laws with less than 36% with Official Community Plans Source: Regional Planning, a presentation by Municipal Affairs and the Municipal Capacity Development Program. MiilCiDMunicipal Capacity Devel opment Program (MCDP) • Assist municipalities in building capacity for ppg;lanning; • further the adoption of inter-municipal growth management plans to attract and effectively manage economihddlic growth and development; • foster long term working relationships amongst municipalities, including First Nations and Métis communities, to enhance communication and collaboration across the province; and, • promote cooperation among urban, rural and northern municipalities to deliver more accessible and cost effective services . MCDP Services The program focuses on a four of key areas for servidlitbildllice delivery to build local capac ity: 1. Facilitation- promote open communication and collaboration amongst ur ban, rura l, an d nor thern mun ic ipa lities an d o ther applicable stakeholders. 2. Education – develop and partner to deliver a number of workhkshops an difd informa tion sess ions on issues suc h as reg iona l planning and preparing funding proposals.