Peter Maurin Winter 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Easy Essays by Peter. Maurin

31st Annlversar~ Issue THE CATHOLIC WORKER Subacriptiona Vol. :XXX No. 10 MAY, 1964 25o Per Year Price le ---·--------------------------------------------""""---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Easy Essays by Peter. Maurin BLOWING THE DYNAMITE We heard about and hospitality .is still practiced Writing ab<>ut the Catholic Ohuroh, all kinds of empires, in Mahometan countries. including the British Emplre, But the duty of hospitality a radical writer says: but never about is neither taught nor praetlced "Rome will have to do more an Irish Empire, in Christian countries. than to play a waiting game1 because the Irish she will have to use did not bother ab<>ut emplrea HOUSES OF some of the dynamite when they were busy "CATHOLIC ACTION" inherent in her IJ1essage." doing good. To blow the dynamite Catholic Houses of Ho9Pltality The Irish scholars established should be more than free guest of a message agricultural centers houses is tJhe only way all over Europe to make the message dynamic. for the Catholla unemployed. where they combined They could be vocational tralnlni If the Catholic Chureh Cult- schools, is not today that fa to say, liturgy, the dominant social dynamic force, Including the trainlnf far the with Culture- priesthood, it h because Catholie scholars that is to say, literature, have failed to blow the dynamite as Father Corbett proposes. with Cultivatlon- They could be Oatholfo readln1 of the Church. that ls to say, agriculture. rooms, Catholic scholars And the word America as Father Mcsorley proposes. have taken the dynamite was for the 11.rst time They could be Catholic Instruction of the Church, printed on a map Schools, have wrapped it up in a town ln east France aa Father Cornelius Hayes in nice .phraseology, proposes. -

Cathlic Worker 7-10-07-Book-Format.Indd

Progress and Poverty Roots of the Catholic Worker Movement Henry George DISTRIBUTISM: Why There Are Recessions And Poverty Amid Plenty- Ownership of the Means of Production and And What To Do About It! Alternative to the Brutal Global Market One of the world’s best-sell- ing books on political econ- by Mark and Louise Zwick omy edited and abridged for modern readers. Many economists and politicians foster the illu- sion that great fortunes and poverty stem from the presence or absence of individual skill and risk- taking. Henry George, by contrast, showed that the wealth gap occurs because a few people are allowed to monopolize natural oppor- tunities and deny them to others. George did not ad- vocate equality of income, the forcible redistribution of wealth, or government management of the econo- my. He simply believed that in a society not burdened by the demands of a privileged elite, a full and satisfying life would be attainable by everyone. Abridged and Edited by Bob Drake August 2002 July Worker Houston Catholic Paperback 325 pp. 2006 ISBN 0-911312-98-6 Price: $12.95 (Plus Shipping) Special Edition for TWO VIEWS OF SOCIAL JUSTICE: Special $10.00 for attendees of Two Views of Social Justice: A Geogist/Catholic Dialogue A GEORGIST / CATHOLIC DIALOGUE Sponsored by the University of Scranton, Publisher: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation www.schalkenbach.org Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, and Progress and Poverty Book Website www.progressandpoverty.org Council of Georgist Organizations July 22 - 27, 2007 The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation 149 Madison Avenue, Suite 601, New York, NY 10016-6713 Roots of the Catholic Worker Movement: “It was hard for me to understand what he meant, thinking as I always had in terms of cities and immediate need of men for their weekly pay check. -

1990 Joe Holland

FREE PDF EDITION - PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE FOR NON-COMMERCIAL PURPOSES FREE PDF EDITION - PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE FOR NON-COMMERCIAL PURPOSES FREE PDF EDITION - PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE FOR NON-COMMERCIAL PURPOSES PETER MAURIN'S ECOLOGICAL LAY NEW MONASTICISM A Catholic Green Revolution Developing Rural Ecovillages, Urban Houses of Hospitality, & Eco-Universities for a New Civilization JOE HOLLAND Pacem in Terris Press Monograph Series PACEM IN TERRIS PRESS Devoted to the memory of Saint John XXIII, Founder of Postmodern Catholic Social Teaching, and in support of a Postmodern Ecological Global Civilization and a Postmodern Ecological World Church www.paceminterrispress.net FREE PDF EDITION - PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE FOR NON-COMMERCIAL PURPOSES Copyright © 2015 Joe Holland All Rights Reserved ISBN-13: 978-0692522806 ISBN-10: 0692522808 PACEM IN TERRIS PRESS is the publishing arm of the PACEM IN TERRIS GLOBAL LEADERSHIP INITIATIVE. The Initiative calls for an authentically postmodern human and Christian renaissance that will be holistically artistic, intellectual, and spiritual, and that will serve the global regeneration of ecological, social, and spiritual life. The Initiative is sponsored by PAX ROMANA Catholic Movement for Intellectual & Cultural Affairs USA 1025 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite 1000 Washington DC 20036 www.pax-romana-cmica-usa.org FREE PDF EDITION - PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE FOR NON-COMMERCIAL PURPOSES Dedicated to my visionary and inspiring friend MABEL GIL who grew up close to the Catholic Worker community as playmate and companion of Tamar, daughter of Dorothy Day, Both Mabel and Tamar were tutored by Peter Maurin Now in her nineties, Mabel still speaks with love's prophetic voice FREE PDF EDITION - PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE FOR NON-COMMERCIAL PURPOSES Doomsday predictions can no longer be met with irony or distain. -

Pacifism a Libertarian Approach on Pilgrimage, ·A Worker's Apostolate

CATHOLIC WORKER Subscription: Vol. XVII No. 10 25c Per Year Price le Pacifism On Pilgrimage, By WILLIAM GA UCHA T By DOROTHY DAY I suppose I am a pacifist be Once upon a time in the early cause I am a Catholic. days of St. Francis there was a In the confusion of thought, Mi. Luchesio who was a married hysteria, and unreasoning fear man and very rich. He had added present in the news Q.ispatches, field on field and l;lad cornered and spread by newspaper and the grain market and people's magazine .columnists and radio bread. He knew how to make commentators, the clearcut logical money and he piled up his for stand of conscientious objection to tune. He had a wife by the name the use of force grows more con of Bona. • vincing to a person with a right Then suddenly he heard St. Christian conscience. The view in Francis preaching, and he re the secular press disregards justice pented of his sins and made up and morality completely. Expedi his mind to restore all that he had ency is the touchstone. General stolen from -the poor, ·for that is Eisenhower stated it succinctly: how he had come to look at his "The only way the U. S. can look life then. His reformation was at the present world situation is sudden and thorough and when he through the glasses of enlightened started to give away all his money, self interest." · his wife Bona protested, and then he had to convert her. Or maybe But the pacifist looks at the St. -

The Long Loneliness

The Long Loneliness Dorothy Day The Catholic Worker, February 1952, 3. Summary: Eight excerpts from The Long Loneliness around the themes of community and work as envisioned by Peter Maurin: · The meaning of liturgy in revolutionary times · Peter Maurin’s vision of community in farming communes · A community of families as a lay form of religious life · Mutual aid and giving to increase love · Peter’s emphasis on work over wages and ownership · Importance of a philosophy of work based on being made in the image and likeness of God · Self-sufficiency in food · The difficulty of restoring community on the land (DDLW #628). (The following is an excerpt from Dorothy Day’s new book) One of the great German Protestant theologians said after the end of the last war that what the world needed was community and liturgy. The desire for liturgy, and I suppose he meant sacrifice, worship, a sense of reverence, is being awakened in great masses of people throughout the world by the new revolutionary leaders. A sense of individual worth and dignity is the first result of the call made on them to enlist their physical and spiritual capacities in the struggle for a life more in the keeping with the dignity of man. One might almost say that the need to worship grows in them with the sense of reverence, so that the sad result is giant sized posters of Lenin and Stalin, Tito and Mao. The dictator becomes divine. We had a mad friend once, a Jewish worker from the East Side, who wore a Rosary around his neck and came to us reciting the Psalms in Hebrew. -

American Religious History Parts I & II

American Religious History Parts I & II Patrick N. Allitt, Ph.D. PUBLISHED BY: THE TEACHING COMPANY 4840 Westfields Boulevard, Suite 500 Chantilly, Virginia 20151-2299 1-800-TEACH-12 Fax—703-378-3819 www.teach12.com Copyright © The Teaching Company, 2001 Printed in the United States of America This book is in copyright. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of The Teaching Company. Patrick N. Allitt, Ph.D. Professor of History, Emory University Patrick Allitt is Professor of History at Emory University. He was born and raised in England, attending schools in his Midlands hometown of Derby. An undergraduate at Oxford University, he graduated with history honors in 1977. After a year of travel, he studied for the doctorate in American History at the University of California, Berkeley, gaining the degree in 1986. Married to a Michigan native in 1984, Professor Allitt was awarded a postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard Divinity School for the study and teaching of American religious history and spent the years 1985 to 1988 in Massachusetts. Next, he moved to Atlanta, Georgia, where for the last twelve years he has been a member of Emory University’s history department, except for one year (1992–1993) when he was a Fellow of the Center for the Study of American Religion at Princeton University. Professor Allitt is the author of Catholic Intellectuals and Conservative Politics in America 1950-1985 (1993), Catholic Converts: British and American Intellectuals Turn to Rome (1997), and Major Problems in American Religious History (2000) and is now writing a book on American religious history since 1945, to be titled The Godly People. -

OLD TRUTHS for the NEW YEAR from PETER MAURIN a Bourgeois the Nazis, the Fascists, to Make a Living: to the Capitalists That Is What Makes Man Human

r- -. CATHOLIC Sub1cr1ption1 No. 6 25o Per Year Price le . OLD TRUTHS FOR THE NEW YEAR FROM PETER MAURIN A Bourgeois The Nazis, the Fascists, to make a living: to the capitalists that is what makes man human. is a fellow, who tries to be some- and the Bolshevists Stealing, begging, working." or accumulators of labor. Creed and not greed, body are Totalitarians. Stealing is against the law of God WHAT MAKES MAN HUMAN That is what makes man human. by trying to be The Catholic Worker and against the law of men. Charles Peguy used to say: BETTER OR BETTER OFF like everybody, is Communitarian. Begging is against the law of men, "There are two. things in this The world would be better off, which makes him THE C. P. AND C. M. but not against the law of God. world, if people tried a nobody. The Communist Party Working ls neither against the law politics and mysticism." to become better. of God - , A Dictator cretlits bourgeois capitalism Politics is just politics And people would is a fellow with an historic mission. nor against the law of men. and is not worth bothering about become better . -who does not hesitate The Communitarian Movement "But they say but mysticism is mysterious if they stopped trying,.. to strike you over the head condemns it to be better off. if you refuse to do on general principles. For when i:verybody 'tries what he wants you to do. The Communist Party to become better 'off, A Leader is a iellow throws the monkey-wrench nobody is better off. -

These Strange Criminals: an Anthology Of

‘THESE STRANGE CRIMINALS’: AN ANTHOLOGY OF PRISON MEMOIRS BY CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTORS FROM THE GREAT WAR TO THE COLD WAR In many modern wars, there have been those who have chosen not to fight. Be it for religious or moral reasons, some men and women have found no justification for breaking their conscientious objection to vio- lence. In many cases, this objection has lead to severe punishment at the hands of their own governments, usually lengthy prison terms. Peter Brock brings the voices of imprisoned conscientious objectors to the fore in ‘These Strange Criminals.’ This important and thought-provoking anthology consists of thirty prison memoirs by conscientious objectors to military service, drawn from the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and centring on their jail experiences during the First and Second World Wars and the Cold War. Voices from history – like those of Stephen Hobhouse, Dame Kathleen Lonsdale, Ian Hamilton, Alfred Hassler, and Donald Wetzel – come alive, detailing the impact of prison life and offering unique perspectives on wartime government policies of conscription and imprisonment. Sometimes intensely mov- ing, and often inspiring, these memoirs show that in some cases, indi- vidual conscientious objectors – many well-educated and politically aware – sought to reform the penal system from within either by publicizing its dysfunction or through further resistance to authority. The collection is an essential contribution to our understanding of criminology and the history of pacifism, and represents a valuable addition to prison literature. peter brock is a professor emeritus in the Department of History at the University of Toronto. -

High Mass for Chapel Centennial

The C150atholicWitness The Newspaper of the Diocese of Harrisburg May 11, 2018 Vol. 52 No. 9 March 2, 2018 Prayer Vigil 7:00 P.M. at Holy Name of Jesus Church, Harrisburg. This will include a live enactment of the Sorrowful Mysteries of the Rosary by young people from throughout the Diocese, similar in manyHigh ways to the Mass Living Way for of the Cross. This event will replace the traditional Palm Sunday Youth Mass and Gathering for 2018. All are welcome and encouragedChapel to attend. Centennial March 3, 2018 Opening Mass for the Anniversary Year 10:00 A.M. at Holy Name of Jesus Church, Harrisburg. Please join Bishop Gainer as celebrant and Homilist to begin the anniversary year celebration. A reception, featuring a sampling of ethnic foods from various ethnic and cultural groups that comprise the faithful of the Diocese, will be held immediately following the Mass. August 28-September 8, 2018 Pilgrimage to Ireland Join Bishop Gainer on a twelve-day pilgrimage to the Emerald Isle, sponsored by Catholic Charities. In keeping with the 150th anniversary celebration, the pilgrimage will include a visit to the grave of Saint Patrick, the Patron Saint of the Diocese of Harrisburg. Participation is limited. November 3, 2018 Pilgrimage to Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception CHRIS HEISEY, THE CATHOLIC WITNESS The Entrance Procession is seen during a Solemn Pontifical High Mass celebrated at St. Lawrence Chapel in Harrisburg onApril 24 in observation of the centennial anniversary of theSAVE chapel, currently THE homeDATE to the for Mater this Dei Latin diocesan Mass Community pilgrimage. -

The Pacifist Witness of Dorothy Day Coleman Fannin Mentor

ABSTRACT Solidarity, Compassion, Truth: The Pacifist Witness of Dorothy Day Coleman Fannin Mentor: Barry A. Harvey, Ph.D. The truth of the gospel requires witnesses, and the pacifist witness of Dorothy Day embodies the peaceable character of a church that, in the words of Stanley Hauerwas, “is not some ideal but an undeniable reality.” In this thesis I provide a thick description of Day’s pacifism and order this description theologically in terms of witness. I argue that her witness is rooted in three distinct yet interrelated principles: solidarity with the poor and the enemy through exploring the doctrine of the mystical body of Christ, compassion for the suffering through practicing voluntary poverty and the works of mercy, and a commitment to truth through challenging the logic of modern warfare and the Catholic Church’s failure to live up to its own doctrine. I also argue that Day’s witness is inexplicable apart from her orthodox Catholicism and her life among the poor at the Catholic Worker. Copyright © 2006 by Coleman Fannin All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iv CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1 Character and Practice 4 CHAPTER TWO: SOLIDARITY 12 Identification with the Masses 12 Transforming the Social Order 21 Natural and Supernatural 27 CHAPTER THREE: COMPASSION 42 The Personalist Center 42 Obedience and the Little Way 53 Disarmament of the Heart 61 CHAPTER FOUR: TRUTH 76 Clarification of Thought 77 Challenging Her Church 83 Perseverance of a Saint 95 CHAPTER FIVE: WITNESS 111 The Church, the State, and the Sword 112 Incarnational Ethics 120 Beyond Liberal and Conservative 132 BIBLIOGRAPHY 152 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful to the administration, faculty, and students of Baylor University’s George W. -

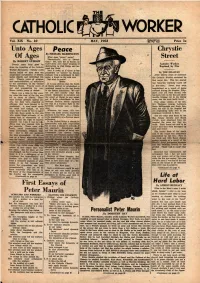

Peter Maurin Persona List Peter Maurin

THB CATHOllG WORKER No., 10 Subecription1 Price le Vol. XIX 2lo Per Year I Unto Ages Peace Chrystie By MICHAEL HARRINGTON . .Of Age~ What does "peace" mean? Street Theoretically, this is "peace By ROBERT LUDLOW time." Yet, men die in Korea, in Twenty years ha.'lle _ gone by Indo-China, men make weapons of / Catholic Worker since the founding of the Catholic destruction in Oak Ridge and be Baptized by Fire yond the Urals. Worker Movement. Twenty years Now it looks as if there is the during which we have seen the possibility of "peace" in Korea, By TOM SULLIVAN progressive curtailment of liberty, perhaps even a settlement in Ger / After t,,{enty years of existence social liberty and individual lib many, a break in the cold war. the Catholic Worker sustained its erty. Twenty years of progres But what is peace? first major fire. This fire started sive materialization, of subjection · Korea last Saturday morning (April 19) to the unfreedom of th~ various It is now obvious that the death Welfare States. Twenty years of of Stalin started, or symbolized, a ~t five-thirty. Seven men were war and preparation for war. profound unrest in the top levels hospitalized as a result of burns Hence twenty~ years of defeat. · ·of the Soviet bu,reacracy. We can suffered during· the dis.aster. Fifty There was a time in this ·coun n.ot yet tell exactly what this three year old John Simms, who try when the tone of the day was means. Malenkov is certainly not has been with us for the past three s~t in terms of liberty. -

Libertarian Socialism

Libertarian Socialism PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sun, 12 Aug 2012 19:52:27 UTC Contents Articles Libertarian socialism 1 The Venus Project 37 The Zeitgeist Movement 39 References Article Sources and Contributors 42 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 43 Article Licenses License 44 Libertarian socialism 1 Libertarian socialism Libertarian socialism (sometimes called social anarchism,[1][2] and sometimes left libertarianism)[3][4] is a group of political philosophies that promote a non-hierarchical, non-bureaucratic society without private property in the means of production. Libertarian socialists believe in converting present-day private productive property into the commons or public goods, while retaining respect for personal property[5]. Libertarian socialism is opposed to coercive forms of social organization. It promotes free association in place of government and opposes the social relations of capitalism, such as wage labor.[6] The term libertarian socialism is used by some socialists to differentiate their philosophy from state socialism[7][8] or by some as a synonym for left anarchism.[1][2][9] Adherents of libertarian socialism assert that a society based on freedom and equality can be achieved through abolishing authoritarian institutions that control certain means of production and subordinate the majority to an owning class or political and economic elite.[10] Libertarian socialism also constitutes a tendency of thought that