'Raised by Wolves'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lykke Li Stays True to Her Style on 'Wounded Rhymes'

TODAY’s WEATHER LIFE SPORTS Review of Lykke Li’s new Sports writer David Namm album “Wounded Rhymes” reflects on last week’s loss to SEE PAGE 5 Richmond SEE PAGE 7 Mostly Sunny 79 / 54 THE VANDERBILT HUSTLER THE VOICE OF VANDERBILT SINCE 1888 MONDAY, MARCH 21, 2011 WWW .INSIDEVANDY.COM 123RD YEAR, NO. 26 CAMPUS NEWS CAMPUS NEWS University and community come Lambda together to show support for Japan kicks off LUCAS LOFFREDO weeklong Staff Writer Several hundred Vanderbilt celebration University students and Nashville community members came together in Benton Chapel KYLE BLAINE Friday for a candlelight vigil News Editor for the victims of the Japanese Tsunami. The rainbow flag will be flying The service included high this week, as the Vanderbilt speeches of support by lesbian, gay, bisexual and Vanderbilt Provost and Vice transgender community comes Chancellor for Academic Affairs together to celebrate the gains Richard McCarty, President of made by the movement this Vanderbilt Interfaith Council year. Eric Walk, and Vanderbilt Rainbow ReVU, the Vanderbilt professor James Auer from the Lambda Association’s weeklong university’s Center for U.S.- celebration of the LGBT Japan Studies and Cooperation, movement, features a variety as well as a church-wide candle of programming including lighting ceremony, a slideshow socials, awareness events, film of pictures from the relief effort screenings and lectures as a in Japan and a performance way to commemorate the year’s by the Vanderbilt Chamber efforts taken by the LGBTQI Singers. community on the university’s Vanderbilt junior Cole Garrett campus. and senior Mana Yamaguchi, Ethan Torpy, president of the who organized the event, were Vanderbilt Lambda Association, pleased with the amount of said he is excited to celebrate people that showed up. -

Lykke Li Featured in Third Episode of Wetransfer's 'Work in Progress' Series

⏲ 17 October 2018, 16:00 (CEST) Lykke Li Featured in Third Episode of WeTransfer's 'Work In Progress' Series Lykke Li opens up for the first time about the death of her mother, the birth of her child and the end of her relationship in the third episode of WeTransfer’s documentary series. October 17, 2018 - The latest episode of WeTransfer’s new series about the creative process, Work In Progress, launches today. It focuses on iconic Swedish indie-pop artist Lykke Li and can be watched on WeTransfer’s editorial platform WePresent here. In the short film (just over 6 minutes), set to Lykke Li’s latest album so sad so sexy, the acclaimed singer-songwriter gives an intimate account of her own real-life struggles in recent years. Lykke Li talks about the loss of a parent, becoming a mother and having her heart broken - and how she emerged stronger and more empowered, both mentally and creatively. Produced by Pi Studios and directed by Kaj Jefferies and Alice Lewis on 16mm film, the episode is dreamlike and melancholic at times but always underlined with a unique, raw feminine beauty. The short film acts as a candid interview and offers viewers an intimate insight into Lykke Li’s life, with personal video camera recordings of her as a child and growing up. In the footage, Lykke Li express her views on love and pain and the therapeutic nature of the creative process. This is the third episode of Work In Progress - a documentary series which celebrates the spirit of creative collaboration which defines WeTransfer's products. -

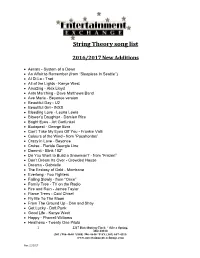

String Theory Song List

String Theory song list 2016/2017 New Additions Aerials - System of a Down An Affair to Remember (from “Sleepless In Seattle”) Al Di La - Trad All of the Lights - Kanye West Amazing - Alex Lloyd Ants Marching - Dave Matthews Band Ave Maria - Beyonce version Beautiful Day - U2 Beautiful Girl - INXS Bleeding Love - Leona Lewis Blower’s Daughter - Damien Rice Bright Eyes - Art Garfunkel Budapest - George Ezra Can’t Take My Eyes Off You - Frankie Valli Colours of the Wind - from “Pocahontas” Crazy in Love - Beyonce Cruise - Florida Georgia Line Dammit - Blink 182* Do You Want to Build a Snowman? - from “Frozen” Don’t Dream Its Over - Crowded House Dreams - Gabrielle The Ecstasy of Gold - Morricone Everlong - Foo Fighters Falling Slowly - from “Once” Family Tree - TV on the Radio Fire and Rain - James Taylor Flame Trees - Cold Chisel Fly Me To The Moon From The Ground Up - Dan and Shay Get Lucky - Daft Punk Good Life - Kanye West Happy - Pharrell Williams Heathens - Twenty One Pilots 1 2217 Distribution Circle * Silver Spring, MD 20910 (301) 986-4640 *(888) 986-4640 *FAX (301) 657-4315 www.entertainmentexchange.com Rev: 11/2017 Here With Me - Dido Hey Soul Sister - Train Hey There Delilah - Plain White T’s High - Lighthouse Family Hoppipola - Sigur Ros Horse To Water - Tall Heights I Choose You - Sara Bareilles I Don’t Wanna Miss a Thing - Aerosmith I Follow Rivers - Lykke Li I Got My Mind Set On You - George Harrison I Was Made For Loving You - Tori Kelly & Ed Sheeran I Will Wait - Mumford & Sons -

Set List Select Several Songs to Be Played at Your Event / Party

FORM: SET LIST SELECT SEVERAL SONGS TO BE PLAYED AT YOUR EVENT / PARTY SONGS YOU CAN EAT AND DRINK TO MEDLEYS SONGS YOU CAN DANCE TO ELO - Mr. Blue Sky Lykke Li - I follow Rivers St. Vincent - Digital Witness Elton John - Tiny Dancer Major Lazer – Lean On Stealers Wheel - Stuck in the Middle With You Beach Boys - God Only Knows Daft Punk Medley Adele - Rolling in the Deep Empire of the Sun - Walking On a Dream Mariah Carey - Fantasy Steely Dan - Hey Nineteen Belle and Sebastian - Your Covers Blown 90's R&B Medley Amy Winehouse - Valerie Feist - 1,2,3,4 Mark Morrison - Return of the Mack Steely Dan - Peg Black Keys - Gold On the Ceiling TLC Ariel Pink - Round + Round Feist - Sea Lion Woman Mark Ronson - Uptown Funk Stevie Nicks - Stand Back Bon Iver – Holocene Usher Beach Boys - God Only Knows Fleetwood Mac - Dreams Marvin Gaye - Ain't No Mountain High Enough Stevie Wonder - Higher Ground Bon Iver - Re: Stacks Montell Jordan Beck - Debra Fleetwood Mac - Never Going Back MGMT - Electric Feel Stevie Wonder - Sir Duke Bon Iver - Skinny Love Mark Morrison Beck - Where It’s At Fleetwood Mac - Say You Love Me Michael Jackson - Human Nature Stevie Wonder- Superstition Christopher Cross - Sailing Next Belle and Sebastian - Your Covers Blown Fleetwood Mac - You Make Lovin Fun Michael Jackson - Don’t Stop Til You Get Enough Supremes - You Can't Hurry Love David Bowie - Ziggy Stardust 80's Pop + New Wave Medley Billy Preston - Nothing From Nothing Frank Ocean – Lost Michael Jackson - Human Nature Talking Heads - Burning Down the House Eagles - Hotel California New Order Black Keys - Gold On the Ceiling Frankie Vailli - December 1963 (Oh What A Night) Michael Jackson - O The Wall Talking Heads - Girlfriend is Better ELO - Mr. -

LYKKE LI RELEASES MUSIC VIDEO for “Hard Rain” from FORTHCOMING ALBUM So Sad So Sexy out JUNE 8TH VIA RCA RECORDS Watch “Hard Rain”

LYKKE LI RELEASES MUSIC VIDEO FOR “hard rain” FROM FORTHCOMING ALBUM so sad so sexy OUT JUNE 8TH VIA RCA RECORDS Watch “hard rain”: http://smarturl.it/hardrainV (New York – May 23, 2018) Los Angeles based, Swedish vocalist, producer, and songwriter Lykke Li released a seductive video over this past weekend via her story on Instagram for her single “deep end” shot entirely on an iPhone. Today, she releases part two of that love story with the cinematic video for album track “hard rain” directed by Anton Tammi. Click HERE to watch “deep end” and HERE to watch the video for “hard rain.” “hard rain” expands on the “deep end” music video, showing viewers the continuation of the wild relationship. The vertical iPhone-shot video for “deep end” was filmed during the making of the video for “hard rain,” both shot on location in Mexico City with actor Moley Talhaoui and directed by Anton Tammi. These two songs, plus the track “utopia” released by Lykke last week, mark the long-awaited coming of so sad so sexy, Lykke Li’s fourth full-length album and follow-up to 2014’s critically acclaimed I Never Learn, due June 8th via RCA Records, her first release with the label. so sad so sexy is available for pre- order now. The album’s lead single, “deep end” was produced by Jeff Bhasker, Malay, and T-Minus and album track “hard rain,” was produced by Rostam Batmanglij. This summer, Lykke will be performing at the BBC’s Biggest Weekend Festival in Belfast, All Points East in London, Chicago’s Lollapalooza and more. -

AN IRISH DAVID by PAUL HARRIS CANTLE

BONO: AN IRISH DAVID by PAUL HARRIS CANTLE Thesis submitted to The Faculty of Theology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Theology) Acadia University Spring Convocation 2013 © by PAUL HARRIS CANTLE, 2012 This thesis by PAUL HARRIS CANTLE was defended successfully in an oral examination on NOVEMBER 26, 2012. The examining committee for the thesis was: ________________________ Dr. Anna Robbins, Chair ________________________ Dr. Kevin Whetter, External Reader ________________________ Dr. Carol Anne Janzen, Internal Reader ________________________ Dr. William Brackney, Supervisor This thesis is accepted in its present form by the Division of Research and Graduate Studies as satisfying the thesis requirements for the degree Master of Arts (Theology). …………………………………………. ii" I, PAUL HARRIS CANTLE, grant permission to the University Librarian at Acadia University to reproduce, loan or distribute copies of my thesis in microform, paper or electronic formats on a non-profit basis. I, however, retain the copyright in my thesis. ______________________________ Author ______________________________ Supervisor ______________________________ Date ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! iii" Table!of!Contents! " Abstract"........................................................................................................................................................"vi" Acknowledgements"................................................................................................................................"vii" -

So Sad So Sexy out TODAY, JUNE 8TH VIA RCA RECORDS

LYKKE LI RELEASES FOURTH STUDIO ALBUM so sad so sexy OUT TODAY, JUNE 8TH VIA RCA RECORDS ANNOUNCES “SO SAD SO SEXY” FALL NORTH AMERICAN AND EUROPEAN TOUR WATCH LAST NIGHT’S PERFORMANCE ON LATE SHOW WITH STEPHEN COLBERT HERE COVER ART + PRESS PHOTO HERE (New York -- June 8, 2018) Today, Los Angeles based, Swedish vocalist, producer, and songwriter Lykke Li releases her critically acclaimed fourth studio album so sad so sexy via RCA Records. so sad so sexy is available now across all digital service providers: http://smarturl.it/sosadsosexy The release of the album will be celebrated with the “so sad so sexy” fall tour, presented by YOLA Mezcal, that will run throughout major cities in North America and Europe including New York, Los Angeles, Toronto, London, Paris, and more. The tour will kick off on October 5th in Washington, D.C. with general on-sale tickets becoming available in the UK on Wednesday, June 13 at 9am UK/10am CET and on Friday, June 15 at 10am local time here. In anticipation for her tour, Lykke Li has performed on several festivals outside of the US, including last month’s BBC’s Biggest Weekend Festival in Belfast, All Points East in London, and will be performing at Lollapalooza, and more. See full tour dates below or visit lykkeli.com for complete schedule. Prior to release, Lykke revealed multiple tracks including the album’s lead single “deep end,” followed by “hard rain,” “utopia,” “two nights feat Aminé,” and “sex money feelings die.” Lykke Li released two highly seductive videos, one for single “deep end” shot entirely on an iPhone, and released part two of that love story with the cinematic video for album track “hard rain” directed by Anton Tammi. -

LYKKE LI ANNOUNCES FOURTH STUDIO ALBUM So Sad So Sexy

LYKKE LI ANNOUNCES FOURTH STUDIO ALBUM so sad so sexy OUT JUNE 8TH VIA RCA RECORDS SINGLE “DEEP END” + TRACK “HARD RAIN” AVAILABLE NOW COVER ART + PRESS PHOTO HERE PHOTO CREDIT: CHLOE LE DREZEN (New York – April 19, 2018) Los Angeles based, Swedish vocalist, producer, and songwriter Lykke Li today releases new single “deep end” and additional track “hard rain.” The songs mark the long- awaited coming of so sad so sexy, Lykke Li’s fourth full-length album and follow-up to 2014’s critically acclaimed I Never Learn, due June 8th via RCA Records, her first release with the label. so sad so sexy is available for pre-order now including the album’s lead single, “deep end,” produced by Jeff Bhasker, Malay, and T-Minus and “hard rain,” produced by Rostam Batmanglij. Listen to “deep end”: http://smarturl.it/LLDeepEnd Listen to “hard rain”: http://smarturl.it/LLHardRain Since the release of her debut EP Little Bit in 2008, Lykke Li has become an iconic staple of the indie-pop world with a decade-spanning career. With three celebrated studio albums, Lykke received critical raves from “Best Album of the Year” nods from the likes of The New York Times and Rolling Stone to performing at the world’s most revered music festivals including Glastonbury and Coachella. Prior to recording this album, Lykke was busy nurturing liv, her love-child with Andrew Wyatt, Björn Yttling, Pontus Winnberg and Jeff Bhasker, which allowed this collective a mutual creative outlet. Outside of music, Lykke Li is a partner in YOLA Mezcal - a brand created in collaboration with her friends Gina Correll Aglietti (chef and stylist) and Yola Jimenez (activist and Mexican entrepreneur), who the mezcal is named after. -

EVALUATING BONO's PERSONALITY the Fly Evaluating

Bono’s Personality 1 Running head: EVALUATING BONO’S PERSONALITY The Fly Evaluating the Personality of Paul Hewson (a.k.a Bono) Brian Berry Box 31 Atlantic Baptist University PS2033 Dr. Edith Samuel November 24, 2008 Bono’s Personality 2 Abstract The purpose of this paper is to discuss and analyse the personality of Paul Hewson, better known to the world as “Bono” As one reads through this paper he or she will see how the different aspects of Bono’s personality mesh together to make him the person he is. One will also come to understand how aspects of Bono’s personality relate to the ideas of certain personality theorists. Bono’s Personality 3 The person whose personality will be discussed and analyzed from multiple perspectives is none other than Paul Hewson, better known to the world by his stage name, Bono. He is best known for his participation in the band U2 as their lead vocalist and occasional rhythm guitar player for the entirety of the band’s existence (from 1976 to present day). He is also known as of lately for his humanitarian work with the “One” campaign to try to eliminate poverty in Africa. Bono has been known to be very outspoken on issues that he deems important such as this crisis of poverty in Africa and his dream to see that become an actual non issue by eradicating poverty altogether. (Maddy Fry, Bono Biography http://www.atu2.com/band/bono/ ) Like everyone else in this world the personality of Paul Hewson (Bono) began to form at birth. -

U2tour.De Travel Guide Dublin & Ireland

The U2Tour.de – Travel Guide Dublin & Ireland U2Tour.de Travel Guide Dublin & Ireland Version 6.0 / September 2020 © U2Tour.de Version 6.0 / 09-2020 Page 1 The U2Tour.de – Travel Guide Dublin & Ireland Contents 1 Windmill Lane - Windmill Lane Studios (demolished) ...................................................................... 6 2 Dockers Pub (closed) .......................................................................................................................... 6 3 Principle Management Offices (moved) ............................................................................................. 7 4 Hanover Quay Studios ........................................................................................................................ 7 5 Windmill Lane Recording Studios (Ringsend Road) ......................................................................... 8 6 Factory Studios (demolished) ............................................................................................................ 9 7 East Link Bridge & Grand Canal Docks & U2 Tower ......................................................................... 9 8 3Arena (The Point Depot Theatre / The O2) ..................................................................................... 10 9 The Clarence Hotel ............................................................................................................................ 11 10 The Project Arts Centre .................................................................................................................... -

{TEXTBOOK} Where the Streets Have 2 Names : U2 and the Dublin

WHERE THE STREETS HAVE 2 NAMES : U2 AND THE DUBLIN MUSIC SCENE, 1978- 1981 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Patrick Brocklebank | 246 pages | 10 Jun 2014 | Liberties Press Ltd | 9781907593574 | English | Ireland Where the Streets Have 2 Names : U2 and the Dublin Music Scene, 1978- 1981 PDF Book For the follow-up to War, U2 entered the studios with co-producers Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois, who helped give the resulting album an experimental, atmospheric tone. One email every morning As soon as new articles come online. Mission Impossible Theme. It made its live debut in Birmingham, England on August 3, , with the remaining performances occurring during the North American leg of the tour. Rathcoole Co Dublin is within city reach but has all the calm of the country. Electrical Storm. A triumph of science and innovation. The Fanning Sessions Archive random Irish radio recordings from the s on. Type keyword s to search. Dirty Day. It was also used in the movie Mr. Released in November , it hit the top of the Billboard charts and quickly gained platinum status. Bono seems to be talking about escaping from such a flawed place and going to someplace better. The death of his mom, Iris, when he was 14, hangs heavy. And many other things. This is the story of a group of extraordinary people who were brave, bold and groundbreaking enough to leave their mark on an incredible time of change in Ireland and the world. Email required Address never made public. Zooropa To some, this album represents another Rattle and Hum -style overreach, taking a once-great idea incorporating electronic beats and textures and grinding it into dust. -

National Geographic Entertainment a 3Ality

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC ENTERTAINMENT präsentieren A 3ALITY DIGITAL Production ab 12. NOVEMBER im Kino Ein Film von CATHERINE OWENS und MARK PELLINGTON mit BONO, THE EDGE ADAM CLAYTON, LARRY MULLEN JR. (Filmlänge 85 Min.) im Verleih Praesens-Film AG Münchhaldenstrasse 10 Postfach 919 8034 Zürich Telefon 044 422 38 33 Telefax 044 422 37 93 E-Mail [email protected] Website www.praesens.com 1 Informationen zur Produktion DER INHALT „U2 3D“ ist der erste digitale Live-Performance-Film in 3D. Die Produktion bietet ein einmaliges Kinoerlebnis und versetzt die Zuschauer mitten in das Publikum eines Stadion-Konzerts - gespielt von einer der berühmtesten Bands der Welt. Durch die Verschmelzung von neuester, digitaler 3D-Technik und einem perfekten Surround- Sound mit dem Erlebnis eines Live-Konzerts von U2 entsteht ein unglaubliches Kinoevent – anders als alle 3D- Konzertfilme, die es je gab. Die Aufnahmen entstanden in Südamerika im letzten Teil der „Vertigo“ Tour. „U2 3D“ entführt die Zuschauer in eine neue Dimension des Filmemachens und nimmt sie mit auf eine außergewöhnliche Reise, die sie niemals vergessen werden! DIE PRODUKTION Mehr als ein Viertel-Jahrhundert verschafften sich U2 nicht nur wegen ihrer musikalischen Fantasie Anerken- nung, sondern auch mit ihrer Fähigkeit, Millionen von Fans mit neuen Technologien zu begeistern. Die Live-Shows der Band entführen das Publikum stets in einen außergewöhnlichen und emotionalen Wahrnehmungsraum – sei es durch den bahnbrechenden Einsatz von Videoleinwänden während der „ZooTV“ Tour 1992/93, mit Hilfe von LED-Displays bei der „PopMart“ Tour 1997/98 oder jüngst mittels perlenartigen, beleuchteten Video-Vorhängen über der Bühne bei der „Vertigo“ Tour 2005/06.