The History of the Scout Wood Badge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uniform Policy 2020

Uniform Policy Version: 2020/v1 Revision Date: 25 February 2020 This Policy is the copyright property of SCOUTS South Africa (SSA) and may only be reproduced, duplicated or published for the pursuit of the aims of SSA as stated in the registered constitution of that body. Reproduction, redaction or publication for any other purpose is only permitted on the express written permission of the Chief Scout or their delegated representative. SSA reserves the right to grant such permission. Requests for any such activity should be directed in writing to the SSA National Head Office or to [email protected]. Table of Contents 1. Right and Entitlement to wear Uniform ...................................................... 5 2. Alteration of Uniform, Badges or Insignia ................................................... 5 3. Local Event Badges and Insignia ............................................................... 5 4. Safety and Cultural Considerations ............................................................ 5 5. Sourcing of Uniform, Badges and Awards ................................................... 6 6. Uniform Options ..................................................................................... 6 6.1. Meerkat Uniform ............................................................................... 7 6.2. Cub Uniform ..................................................................................... 8 6.3. Scout Uniform ................................................................................... 9 6.4. Rover Uniform ............................................................................... -

The County Executive Committee

The County Executive Committee (References to County also applies to Areas, Regions, Islands and Bailiwicks) FS330079 October/2015 Edition no 5 (103402) 0845 300 1818 The County Executive Committee plays a vital Appoint and manage the operation of any sub- role in the running of a Scout County. Executive Committees, including appointing Chairmen to Committees make decisions and carry out lead the sub-committees. administrative tasks to ensure that the best quality Ensure that Young People are meaningfully Scouting can be delivered to young people in the involved in decision making at all levels within County. the County. The opening, closure and amalgamation of This factsheet should be treated as a guide and Districts and Scout Active Support Units in the read in conjunction with other resources (including County as necessary. The Scout Association’s Policy, Organisation and Appoint and manage the operation of an Rules referred to as POR throughout this Appointments Advisory Committee, including factsheet). appointing an Appointments Committee Chairman to lead it. Further details of the responsibilities of the County Executive Committee can be found in chapters 5 The Executive Committee must also: and 13 of POR. Note that SV in this factsheet Appoint Administrators, Advisers, and Co-opted denotes there is a Scottish variation to that members of the Executive Committee. section of guidance. Approve the Annual Report and Annual Accounts after their examination by an The County Executive Committee appropriate auditor, independent examiner or The Executive Committee exists to support the scrutineer. County Commissioner in meeting the Present the Annual Report and Annual Accounts responsibilities of their appointment. -

Council Recognition Program 2019

Sam Houston Area Council Boy Scouts of America Annual Recognition Reception Chapelwood United Methodist Church November 19, 2019 Recognition Reception Master of Ceremonies ................................................ Diane Cannon Vice Chair-Program Sam Houston Area Council Opening .................................... Youth of Sam Houston Area Council Lifesaving Awards Silver Beaver Awards Presentation ........................... Russell Carman Silver Beaver Selection Committee Chair Patricia Chapela Council Advancement Chair Challenge to Service ................................................ Forrest Bjerkaas Council Commissioner Sam Houston Area Council Reception immediately following in the Fellowship Hall. 2 Distinguished Eagle Scout Award The National Court of Honor of the Boy Scouts of America established the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award in 1969. Since its inception, this prestigious award has been presented approximately 1,500 times nationally. The Sam Houston Area Council's Distinguished Eagle Scout Award recipients are equally representative of the character and successful lifetime achievement and service necessary to be recognized for this honor. The elite list of Distinguished Eagle Scouts named below from the Sam Houston Area Council exemplifies the Eagle Scout Challenge as an example of their lifetime achievement. Honorable Lloyd N. Bentsen, Jr. Jack L. Lander, Jr. Nelson R. Block James A. Lovell, Jr. Gerald P. Carr William P. Lucas M.L." Sonny" Carter Douglas G. MacLean George M. Fleming Carrington Mason Col. Michael E. Fossum Thomas M. Orth Orville D. Gaither, Sr. Robert W. Scott Dr. Robert M. Gates Bobby S. Shackouls Carlos R. Hamilton, Jr., M.D. L.E. Simmons Maj. Gen. Hugh W. Hardy, USMC Howard T. Tellepsen, Jr. Robert R. Herring C. Travis Traylor, Jr. William G. Higgs Frank D. Tsuru Honorable David Hittner John B. -

Wood Badge Generic Brochure.Pub

What is the purpose of Wood Badge? What are the qualifications? How do I register? The ultimate purpose of Wood Badge is to Wood Badge is not just for Scoutmasters. It’s Visit help adult leaders deliver the highest quality for adult Scouters at all levels: Cub Scouts, Boy http://www.pikespeakbsa.org/Event.aspx? Scouting program to young people and help Scouts, Varsity, Venturing, District and Council. id=1957 Review the event information, them achieve their highest potential. Youth older than 18 may attend and do not need then click on the register button. If you It models the best techniques for developing to be registered in an adult leadership role. Here need to make other arrangements for leadership and teamwork among both young are the qualifications: registration / payment, contact Steve people and adults. • Be a registered member of the BSA. Hayes at 719-494-7166 or • Complete basic training courses for your [email protected] How much time will Wood Badge primary Scouting position (see Scouting’s Basic A $50 payment is due at the time of take? Leader Training Courses at right). application. The first 48 fully paid Wood Badge is conducted over two three- • Complete the outdoor skills training Scouters who meet course requirements day weekends scheduled three weeks apart. program appropriate to your Scouting position. will be confirmed for the course. Each weekend begins at 7:30 a.m. Friday and • Be capable of functioning safely in an outdoor environment. What are the Training goes ‘til 4:00pm on Sunday. Your patrol will Prerequisites? have one or two meetings in between the • Complete the Colorado Boy Scout Camps course weekends. -

Spirituality in the Scouts Canada Program a Proposal – December 2011

Spirituality in the Scouts Canada Program a proposal – December 2011 Lord Baden-Powell & Duty to God God is not some narrow-minded personage, as some people would seem to imagine, but a vast Spirit of Love that overlooks the minor differences of form and creed and denomination and which blesses every [person] who really tries to do his [/her] best, according to his [/her] lights, in His service. in “Rovering to Success” Reverence to God, reverence for one’s neighbour and reverence for oneself as a servant of God, are the basis of every form of religion. in “Aids to Scoutmastership” Spirituality means guiding ones’ own canoe through the torrent of events and experiences of one’s own history and of that of [humankind]. To neglect to hike – that is, to travel adventurously – is to neglect a duty to God. God has given us individual bodies, minds and soul to be developed in a world full of beauties and wonders. in “The Scouter” January 1932 The aim in Nature study is to develop a realisation of God the Creator, and to infuse a sense of the beauty of Nature. in “Girl Guiding” Real Nature study means…knowing about everything that is not made by [humans], but is created by God. In all of this, it is the spirit that matters. Our Scout law and Promise, when we really put them into practice, take away all occasion for wars and strife among nations. The wonder to me of all wonders is how some teachers have neglected Nature study, this easy and unfailing means of education, and have struggled to impose Biblical instruction as the first step towards getting a restless, full-spirited boy to think of higher things. -

Role Description for an Assistant County Commissioner (Scout S Network)

Role description for an Assistant County Commissioner (Scout S Network) Item Code Date Mar 2015 Edition no1 0845 300 1818 Title: Assistant County Commissioner (Scout Network). Outline: To work in partnership with the County Commissioner to ensure effective operation of the Scout Network section in their County, in accordance with the Purpose, Principles and Policies of The Scout Association. Responsible to: County Commissioner Responsible for: N/A Main Contacts: County Commissioner, Assistant County Commissioner (Explorer Scouts), District Commissioners, District Network Scout Commissioner, Programme Coordinator(s), District Explorer Scout Commissioners, District Explorer Scout Administrator, Scout Network Members, Local Youth Commissioners, Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Adviser, Queen’s Scout Award Coordinator, Assistant County Commissioners (Scout Network) from other Counties. Appointment Requirements: Must successfully complete the appointment process (including acceptable personal enquiries and acceptance of The Scout Association's policies). During the five months of Provisional Appointment the relevant Getting Started modules must be completed. A Wood Badge must be completed within three years of Full Appointment, and ongoing safety and safeguarding training. Main Tasks Developing a quality Scout Network provision across the County Maintain and grow the Scout Network across the County. Ensure that a quality Scout Network programme is carried out throughout the County. Ensure that Awards are robustly and consistently assessed, including signing certificate request forms for Scout Network Members (Queen’s Scout Award, Explorer Belt, Scouts of the World Award). Maintain a working relationship with District Commissioners, District Scout Network Commissioners, Programme Coordinators, and other Commissioners in the County, particularly providing support in matters relating to the Scout Network Section. -

GIRL GUIDES ASSOCIATION of VICTORIA "Opera Tion Co-Opera Tion" at Jamborella One

MARCH,1979 VOLUME S6 NUMBER 8 GIRL GUIDES ASSOCIATION OF VICTORIA "Opera tion Co-opera tion" at Jamborella One. Details and more pictures on pages 218 and 219. In this issue. Page Archives 237 Awards . 223 Britannia Park 242 Brownies 232 Camp Patanga 217 Encouraging Encounter 221 Go Guiding 233 Guide Shop .. 242 International .. 239 Jamborella One 218 Local Association Section . 231 Matilda Subscription Form 240 Mobile Guide Shop 236 Notices . 220, 222,226, 231,232,238, 240,244 Personnel Changes, etc. 243 Rangering Around . 234 Reporting from Russell Street 216 State Commissioner's Letter 215 Supplementary Activities . 225 Transfers and Waiting Lists 220 Training Calendar 241 Training Pages 227-230 Trefoil Tales .. 238 PUBLI SH ED BY THE GIRL GUIDES ASSOCIATI ON OF VICTORIA MATILDA 20 RUSSELL STR EET, MELBOURNE, VI CTORI A, AUSTRALIA, 3000 State Commisssioner: MRS. J. N. WEST State Secretary: MISS M. W. BARR Assistant State Commissioners: MRS. C. S. ANJOU, MRS. W. J. B. POLLOCK, MRS. S. J. SURRY Editor: MRS. L. I. RICHARDSON, 31 Hampshire Road, Forest Hill, 3131 214 MATILDA The 5th Australian Venture was held in South Australia in January and 66 ranger guides and 10 leaders from Victoria took part in this camp and thoroughly enjoyed themselves. Hello Everyone, The Summer Training Week was well worth Firstly, I must tell you that the new Assistant while; my Assistants and I were able to meet every Chief Commissioner for Australia is Mrs J. L. Car one and it was evident that a great deal was being rick, who took up her appointment on 1 st February, achieved. -

October 2019 Committee Chair: Amy Burdick Staff Advisor: Linda Dieguez Ed.: Michelle Barrentine

Volume 3 Issue 3 October 2019 Committee Chair: Amy Burdick Staff Advisor: Linda Dieguez Ed.: Michelle Barrentine WOOD BADGE HISTORY TIMELINE Scouting, and Wood Badge, are worldwide. Did you reetings from your Alamo Area Council know these facts about Wood Badge? G International Committee members, 1919: First Wood Badge course, Gilwell Park, including a few new folks: England 1936: Gilwell Camp Chief John Skinner Wilson Michelle Barrentine John Douglas conducts Experimental Scout & Rover Wood Badge Jack Hoyle Scott Mikos courses at Schiff Scout Reservation, New Jersey Marcy Roca Richard Ruiz 1948: First official BSA Wood Badge courses, at Schiff & at Philmont. Scouting legend William Warren Wolf “Green Bar Bill” Hillcourt serves as Scoutmaster at Linda Dieguez, Staff Advisor both nine-day courses 1948-58: Mostly national courses conducted, run e welcome your ideas and suggestions, with oversight of the BSA’s Volunteer Training Divi- W as well. Let us hear from you by sion emailing: [email protected] or any 1953-54: A few councils allowed to hold their own committee member. courses, including Cincinnati (1953) and Washing- ton, D.C. (1954) 1958-72: Two variations of the course: a national one for trainers, and a sectional one for commis- sioners and local Scouters. Focus exclusively on Amy Burdick joined Cub Scouting 2 years Scoutcraft ago with her son. She also grew up with skills, the patrol method and requirements a boy Scouting because her dad was very active in would need to earn First Class the Capital Area Council. In addition to being 1967-72: BSA conducts experimental courses that the International Committee chair, Amy has add leadership skills to Wood Badge been a Den Leader, Pack Trainer, and Unit 1973-2002: All Boy Scout Wood Badge courses Commissioner. -

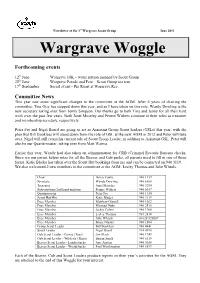

Wargrave Woggle

Newsletter of the 1st Wargrave Scout Group June 2011 Wargrave Woggle Forthcoming events 12th June Wargrave 10K – water station manned by Scout Group 25th June Wargrave Parade and Fete – Scout Group tea tent 17th September Social event – Pig Roast at Wargrave Rec. Committee News This year saw some significant changes to the committee at the AGM. After 6 years of chairing the committee, Tina Otty has stepped down this year, and so I have taken on this role. Wendy Dowling is the new secretary taking over from Jenny Simpson. Our thanks go to both Tina and Jenny for all their hard work over the past few years. Both Janet Moseley and Pennie Withers continue in their roles as treasurer and membership secretary, respectively. Peter Fry and Nigel Board are going to act as Assistant Group Scout leaders (GSLs) this year, with the plan that Bill Bookless will stand down form the role of GSL at the next AGM in 2012 and Peter will take over. Nigel will still retain his current role of Scout Troop Leader, in addition to Assistant GSL. Peter will also be our Quartermaster, taking over from Matt Warms. Earlier this year, Wendy had also taken on administration for CRB (Criminal Records Bureau) checks. Since we run parent helper rotas for all the Beaver and Cub packs, all parents need to fill in one of these forms. Katie Blades has taken over the Scout Hut bookings from me and can be contacted on 940 3119. We also welcomed 2 new members to the committee at the AGM; Lesley Thomas and Julie Wheals. -

Your Movement

Your Movement YOUR MOVEMENT Page 1 Your Movement September 1956 Reprinted 1959 Printed by C. Tinling & Co., Ltd., Liverpool, London and Prescot. The Patrol Books No. 20 YOUR MOVEMENT A record of the outstanding events of the first 50 years of British Scouting selected by REX HAZELWOOD Published by THE BOY SCOUTS ASSOCIATION 25 Buckingham Palace Road London, S.W. 1 Downloaded from: “The Dump” at Scoutscan.com http://www.thedump.scoutscan.com/ Editor’s Note: The reader is reminded that these texts have been written a long time ago. Consequently, they may use some terms or express sentiments which were current at the time, regardless of what we may think of them at the beginning of the 21 st century. For reasons of historical accuracy they have been preserved in their original form. If you find them offensive, we ask you to please delete this file from your system. This and other traditional Scouting texts may be downloaded from The Dump. Page 2 Your Movement 1907. Lt.-Gen. R. S. S. Baden-Powell holds an experimental camp on Brownsea Island, Poole Harbour, to see if his ideas on the training of boys work. The camp, at which there are four patrols of five each, some belonging to the Boys’ Brigade, others sons of friends of B.-P’s, is a happy success. The Patrols wear shoulder knots of coloured wool, the Bulls green, Curlews yellow, Ravens red, and Wolves blue. The boys wear shorts, which is very unusual, and a fleur-de-lys badge. B.-P. finishes writing Scouting for Boys . -

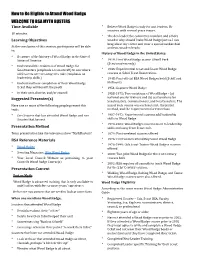

How to Be Eligible to Attend Wood Badge WELCOME to BSA MYTH BUSTERS Time Available • Believe Wood Badge Is Only for Unit Leaders

How to Be Eligible to Attend Wood Badge WELCOME TO BSA MYTH BUSTERS Time Available • Believe Wood Badge is only for unit leaders. Or scouters with several years tenure. 10 minutes. • The den leader, the committee member, and others Learning Objectives wonder why should I take Wood Badge just so I can brag about my critter and wear a special neckerchief At the conclusion of this session, participants will be able and two wooden beads. to: History of Wood Badge in the United States: • Be aware of the history of Wood Badge in the United States of America • 1919: First Wood Badge course Gilwell Park (Scoutmasters only) • Understand the evolution of Wood Badge for Scoutmasters (emphasis on scoutcraft) to one where • 1936: Experimental Scout and Rover Wood Badge all Scouters are encouraged to take (emphasis on courses at Schiff Scout Reservation. leadership skills.) • 1948: First ofdicial BSA Wood Badges held (Schiff and • Understand how completion of their Wood Badge Philmont) ticket they will benedit the youth • 1951: Explorer Wood Badge • in their unit, district, and/or council • 1958-1972: Two variations of Wood Badge – (a) Suggested Presenter(s) national one for trainers and (b) sectional one for Scoutmasters, commissioners, and local Scouters. The Have one or more of the following people present this aim of each course was on Scoutcraft, the patrol topic: method, and the requirements for First Class. • One Scouter that has attended Wood Badge and one • 1967-1972: Experimental courses add leadership Scouter that has not skills to Wood Badge • 1973-2002: Wood Badges courses move to leadership Presentation Method skills and away from Scoutcraft. -

The Scout's Book of Gilwell

The Scout’s Book of Gilwell The Patrol Books . No. 13 THE SCOUT’S BOOK OF GILWELL by JOHN THURMAN Camp Chief Illustrated by John Sweet with a frontispiece by Maurice V. Walter Published by THE BOY SCOUTS ASSOCIATION 25, Buckingham Palace Road London, S.W.I Published, 1951 Printed by C. Tinling & Co. Ltd., Liverpool, London and Prescot Page 1 The Scout’s Book of Gilwell Downloaded from: “The Dump” at Scoutscan.com http://www.thedump.scoutscan.com/ Thanks to Dennis Trimble for providing this booklet. Editor’s Note: The reader is reminded that these texts have been written a long time ago. Consequently, they may use some terms or express sentiments which were current at the time, regardless of what we may think of them at the beginning of the 21st century. For reasons of historical accuracy they have been preserved in their original form. If you find them offensive, we ask you to please delete this file from your system. This and other traditional Scouting texts may be downloaded from The Dump. CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. GILWELL PARK – WHERE AND WHY? 2. A TOUR OF GILWELL 3. WHAT GILWELL OFFERS AND WHAT GILWELL EXPECTS FROM YOU Page 2 The Scout’s Book of Gilwell GILWELL PARK – WHERE AND WHY? uppose for a change we start in the middle. In 1929 the Twenty-first Anniversary Scout S Jamboree was held at Arrowe Park, Birkenhead, and to it came the Scouts of many countries of the world to celebrate the coming of age of Scouting and to honour Baden-Powell, our Founder and Chief Scout.