Shallow Bones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS THE KEYS OF CHRISTMAS David Meyers YouTube Red Feature OPENING NIGHTS Isaac Rentz Dark Factory Entertainment Feature Los Angeles Film Festival G.U.Y. Lady Gaga Rocket In My Pocket / Riveting Short Film Entertainment MR. HAPPY Colin Tilley Vice Short Film COMMERCIALS & MUSIC VIDEOS SOL Republic Headphones, Kraken Rum, Fox Sports, Wendy’s, Corona, Xbox, Optimum, Comcast, Delta Airlines, Samsung, Hasbro, SONOS, Reebok, Veria Living, Dropbox, Walmart, Adidas, Go Daddy, Microsoft, Sony, Boomchickapop Popcorn, Macy’s Taco Bell, TGI Friday’s, Puma, ESPN, JCPenney, Infiniti, Nicki Minaj’s Pink Friday Perfume, ARI by Ariana Grande; Nicki Minaj - “The Boys ft. Cassie”, Lil’ Wayne - “Love Me ft. Drake & Future”, BOB “Out of My Mind ft. Nicki Minaj”, Fergie - “M.I.L.F.$”, Mike Posner - “I Took A Pill in Ibiza”, DJ Snake ft. Bipolar Sunshine - “Middle”, Mark Ronson - “Uptown Funk”, Kelly Clarkson - “People Like Us”, Flo Rida - “Sweet Spot ft. Jennifer Lopez”, Chris Brown - “Fine China”, Kelly Rowland - “Kisses Down Low”, Mika - “Popular”, 3OH!3 - “Back to Life”, Margaret - “Thank You Very Much”, The Lonely Island - “YOLO ft. Adam Levine & Kendrick Lamar”, David Guetta “Just One Last Time”, Nicki Minaj - “I Am Your Leader”, David Guetta - “I Can Only Imagine ft. Chris Brown & Lil’ Wayne”, Flying Lotus - “Tiny Tortures”, Nicki Minaj - “Freedom”, Labrinth - “Last Time”, Chris Brown - “She Ain’t You”, Chris Brown - “Next To You ft. Justin Bieber”, French Montana - “Shot Caller ft. Diddy and Rick Ross”, Aura Dione - “Friends ft. Rock Mafia”, Common - “Blue Sky”, Game - “Red Nation ft. Lil’ Wayne”, Tyga “Faded ft. -

Perform for Free in Our VIRTUAL /INTERACTIVE ITNS Radio Concert Series! ITNS Radio & SWC Global Media, LLC

Perform for free in our VIRTUAL /INTERACTIVE ITNS Radio Concert Series! ITNS Radio & SWC Global Media, LLC Sam Watkins & Fate Train at Boomerz in Austin, Texas (2010) Sam Watkins & Fate Train Rock, Blues and Metal Plays Modal, Jazz Plays Changes! #shorts Ron Jackson DPB "WAKE UP" THE OFFICIAL MUSIC VIDEO World of DPB The Honest Mistake Band THEHONESTMISTAKEBAND (Old Upload) Zelda: The Return of Ganondorf Joseph Blanchette \ DO IT - 2TALLIN & DRAFT Travis Huff Christine Lee - Listen to Your Dreams (Official Music Video) Christine Lee We are One by Nordic Daughter Nordic Daughter Teddy Bop by TSwang Video tswang2 Silent Machines - What Matters The Most Silent Machines Heavy AmericA - "Motor Honey (Peace)" Heavy AmericA "Mary Did You Know" - By Lucas Ciliberti Lucas Ciliberti Waiting Til Dawn "Official Video" PLEASE SUBSCRIBE!! McCUIN *OFFICIAL BAND PAGE* Richard Mulligan and Richard Mulligan on Soap garrisonskunk a few miles down the road Brandon Good Pedal Steel Guitar solo on SAN ANTONIO ROSE John Heinrich show me you vanilla base Vanilla base Guitar Boogie - Arthur Smith DaemonRicks Ali Jacko - Follow My HEART (Official Video) ajackorocksVEVO TK MAFIOSO - " BIGGIE PAC " ( OFFICAL MUSIC VIDEO ) TK Mafioso Illist - What I've Never Felt (Official Music Video) Angels Castle Live - Jimmy Richardson jimjim776 Kayla Cariaga (Kayla C.) - GONE Official Music Video Kayla Cariaga What Do I Know JP Southern Band William T Starzz Going In official video directed by Bryan Eyce Leonard William T. Starzz Johnny Rock Band - Easter Bunny Hop Johnny Rock -

Deputies: Pace Man Pulls Gun on Neighbor Cover Pulledthelinesdown

HOMECOMING: SEE PHOTOS FROM MILTON HIGH’S CELEBRATION PAGE B1 Santa Rosa’s Press Who got married? Who filed for divorce? Find out Gazette on Page A5 Tweet us @srpressgazette and like us on facebook.com Wednesday, October 9, 2013 Find breaking news at www.srpressgazette.com 75 cents Deputies: Pace man pulls gun on neighbor By JASON JANDURA A Charlene Drive resident the vehicle. in a hole,” according to the confronted the man, telling 623-2120 told cops he was standing in The victim said he con- report. him to stay off his property [email protected] his garage with another per- fronted Punzone, who ac- The victim and the other or there would be repercus- son in the Chantilly neigh- cused him of burglarizing person present told deputies sions. Punzone also said he A Pace man pulled a gun borhood off U.S. 90 in Pace. cars in the neighborhood. they feared for their lives. returned later to apologize. on his neighbor and threat- He said a white Toyota Co- The 51-year-old New Yorker Punzone later told author- Deputies arrested and ened to shoot him after ac- rolla slowly drove down the pulled a silver and black ities some of the neighbors charged Punzone with two cusing him of breaking into street and stopped just past handgun from behind his had “pointed fingers” at the counts of aggravated assault CARL cars in the neighborhood, his house. Reports say Carl back and pointed it in the air, Charlene Drive regarding with a weapon without intent PUNZONE according to a sheriff’s office Punzone, 51, originally from saying, “I’m going to put a recent vehicle burglaries in to kill. -

Billboard Magazine

EMI Group as a strategy associate in corporate strate- Cathy gy and business development, Pincus-a former punk Heller's rocker who's a member of Judge, which is headlining first synch appeared in the hardcore-themed Black N' Blue Bowl May 18-19 ABC's "Body at Webster Hall in New York-noticed that EMI's pub- of Proof." lishing firm was shifting its investments away from songwriter deals and channeling them into buying catalog and radio hits. Simultaneously, he saw hun- dreds of millions of dollars from private equity and hedge funds coming into seven or eight indie publish- ing companies. "But the irony of that was that almost none of the funds went into signing songwriters; it all went into investing in existing assets," he recalls. "So when I was trying to figure out what my next job was going to be, I saw how many writers were available. I decided to go in the opposite direction, signing people who would then make songs. "We started with rock bands who were selling a lot of albums, like Chiodos and Rhett Miller. The lat- ter signing helped us attract the serious songwriters. Signing Andrew McMahon brought us into a world where major -label artists would then sign with us, while Q: Tip is a really respected rapper and a great producer who brought us into the world where hip - hop songwriters now consider us," Pincus says. "You Writing Your Own Check will see us working with classic songwriters in the near future." v./Titer Cathy Heller Twice the In return for helping establish the firm, SONGS' re- sponsibility includes career -building. -

Washington Blues Society Talent Guide

In Th s Issue... Blueswoman at Work: Stickshift nnie Polly O’Keary - Our 207 Electric Act Welcom Back, Mr. Buddy Guy! (Photo by Eric Steiner) (Photo by Alex Brikoff) (Photo by Eric Steiner) Letter from the President 2 Valentine’s Day Blues Bash Preview 6 Membership Opportunities 14 Letter from the Editor 3 A Great Send Off! 7 2017 BMA Nominations 14 Offic s and Director 4 Thank you 2016 Donors 10 Blues on the Road 16 On the Cover 4 Street Team Report 12 A Bored Meeting? 17 Letter from Washington Blues Society President Tony Frederickson Hi Blues Fans! and check out the fun! at our website (www.wablues.org), our Facebook page and in the March Bluesletter. We will also We have a ton of fun and new events for you to The final ballot for the Best of the Blues is in this have tickets available as we go out recognize participate in over the next several months! We issue and all dues current members are eligible nominees with their certificates of nomination have partnered with Capps Club, our new home to vote for their favorites! It is a great ballot that at clubs and venues throughout our area! Please for the Blues Bash, in a Dinner & a Show series! our members have nominated and represents a save this very important date as Washington Blues These shows happen every weekend on Sunday wide part of our genre. Many of the established Society honors this past year’s Best in the Blues and will feature a rotating series of bands and performers that are favorites and lots of recognition nominees and the recipients at the show. -

Festival Preview Issue Pickaxe R&B Gorge Blues & Brews Winthrop R&B

Washington Blues Society June 2019 June Bluesletterwww.wablues.org Festival Preview Issue Pickaxe R&B Gorge Blues & Brews Winthrop R&B Billy Joe Huels of The Dusty 45s will be at the Winthrop Rhythm & Blues Festival at The Blues Ranch next month! LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT Hi Blues Fans, WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY Proud Recipient of a 2009 I usually write an annual re- Keeping the Blues Alive Award view at year’s end, but my team has accomplished so much in OFFICERS the first six months 2019, and President, Tony Frederickson [email protected] there is a lot on our calendar Vice President, Rick Bowen [email protected] for the rest of the year, I want- Secretary, Marisue Thomas [email protected] ed to send well-deserved, mid- Treasurer, Ray Kurth [email protected] year shout-outs to our team. Editor, Eric Steiner [email protected] Our Blues Bashes continue to be a big draw and are enjoyed by many members. Amy Sassenberg has done a great job coordinating talent DIRECTORS and adapting to weather and band changes. It seems seamless and Music Director, Amy Sassenberg [email protected] our partnership with Collector’s Choice is growing. Remember to Membership, Chad Creamer [email protected] check out the preview in each Bluesletter and join fellow blues fans Education, Open [email protected] at a Blues Bash! Volunteers, Rhea Rolfe [email protected] Merchandise, Tony Frederickson [email protected] Our Best of the Blues Awards show was a big success this year! We Advertising, Open [email protected] had great attendance and all who came enjoyed themselves. -

GV Smart Vol.016 R0.Hwp

GV Smart Song Pack Vol.016 GV Smart Song Pack Vol.016 SONG LIST Song Title No. Popularized By Composer/Lyricist Dominic Fike / Kevin Anthony 3 NIGHTS 17002 DOMINIC FIKE Carbo ROBERT SHEA TAYLOR / ANDREAO SHAUNEE HEARD / JEFFREY LORBER / JAMES KOWAN LLOYD / PRISCILLA HAMILTON / MARIAH A NO NO 17044 MARIAH CAREY CAREY / CHRISTOPHER WALLACE A WHOLE NEW WORLD (ALADDIN OST) 9264 ZAYN, ZHAVIA WARD Alan Menken AIN'T NOTHING GONNA KEEP ME FROM YOU 17050 TERI DESARIO Barry Gibb ALAALA 4424 FREDDIE AGUILAR ALL TOO WELL 17005 TAYLOR SWIFT Taylor Swift / Liz Rose AMATZ 4425 SHANTI DOPE Rita Sahatçiu / OraNolan Lambroza / Alexandra Tamposi / Alessandro Lindblad / ANYWHERE 17013 RITA ORA Nicholas Gale / Andrew Wotman / Brian Lee APPLE 17000 JULIA MICHAELS Julia Michaels BACK TO LOVE 16986 CHRIS BROWN Alexander Michael Tidebrink Stomberg / Aron Rolf Blom / Christopher Lund BAD 16971 CHRISTOPHER Nissen / Lenno Sakari Linjama BAD GUY 17018 BILLIE EILISH Billie O'Connell / Finneas O'Connell BLITZKRIEG BOP (SPIDERMAN COLVIN DOUGLAS / HYMAN JEFFREY / HOMECOMING) 17025 RAMONES CUMMINGS JOHN / ERDELYI THOMAS Ryan Ogren / Theron Thomas / Dr. BLOW IT ALL 17047 KIM PETRAS Luke / Aaron Joseph / Kim Petras BREATHE IN 17016 FROU FROU Imogen Heap / Guy Sigsworth Alecia B. Moore / John Mcdaid / BROKEN & BEAUTIFUL 16996 KELLY CLARKSON Steve Mac Sean "Puffy" Combs / Steve Jordan / Carlos Broady / Nasheim Myrick / Mason Betha / Greg Prestopino / Matthew Wilder / Sylvia Robinson / CAN'T NOBODY HOLD ME DOWN 17029 PUFF DADDY FT. MASE Melvin Glover / Clifton Chase / Edward -

GV Smart Vol.007 R1

GV Smart Song Pack Vol.007 GV Smart Song Pack Vol.007 SONG LIST Song Title No. Popularized By Composer/Lyricist A CERTAIN SMILE 16233 ENGELBERT HUMPERDINCK Lindy Robbins / Ilsey Juber / Ed Sheeran / Johnny McDaid / William A DIFFERENT WAY 16209 DJ SNAKE FEAT. LAUV Grigahcine / Steve Mac CONWAY TWITTY AND AFTER THE FIRE IS GONE 16252 LORETTA LYNN L. E. White ALL THIS LOVE 16222 EL DEBARGE DeBarge BABY SHARK 16211 PINKFONG Kenneth Edmonds / Antonio BABY-BABY-BABY 16239 TLC Reid / Daryl Simmons GRACENOTE FEAT. CHITO BAKIT GANYAN KA 594 MIRANDA BECAUSE 16262 JULIAN LENNON CLARK DAVE BHATTACHARYYA AJAY / GALLANT BONE+TISSUE 16210 GALLANT CHRISTOPHER JOSEPH III BREAK ON ME 16251 KEITH URBAN Ross Copperman / Jon Nite CLIVILLES ROBERT COULD THIS BE LOVE 16264 SEDUCTION MANUEL Richard Marx / Kenny CRAZY 16202 KENNY ROGERS Rogers BARLETTA GINO MAURICE / BRUZENAK SCOTT / HUDSON DENISE / JEBERG DARE 16194 DAYA JONAS / TANDON GRACE MARTINE FORMAN JON / SIEROTA GRAHAM JEFFERY DAVID / SIEROTA JEFFERY DAVID / SIEROTA NOAH JEFFERY DAVID JOSEPH / SIEROTA DEAR WORLD 16236 ECHOSMITH SYDNEY GRACE ANN DID YOU 4361 DONNY PANGILINAN Ed Sheeran / Benjamin DIVE 16207 ED SHEERAN Levin Julia Michaels D-I-V-O-R-C-E 16253 TAMMY WYNETTE Billy Connolly DOES MY RING BURN YOUR FINGER 16267 LEE ANN WOMACK Julie Miller / Buddy Miller KIANA VALENCIANO FEAT. DOES SHE KNOW 4359 CURTIS SMITH DON'T 16196 ELVIS PRESLEY Jerry Leiber / Mike Stoller DON'T BE SAD 'CAUSE YOUR SUN IS WONDER STEVIE / TAYLOR DOWN 16199 JAMES TAYLOR JAMES VERNON MANDEL JOHNNY / EMILY 16197 ANDY WILLIAMS MERCER JOHN H ENCHANTED 16254 TAYLOR SWIFT SWIFT TAYLOR EVERY MOMENT 16259 JODECI DeGrate JUSTIN BIEBER FEAT. -

Los Angeles April 24–27, 2018

A PR I L 24–27, 2018 1 NORDIC MUSIC TRADE MISSION / NORDIC SOUNDS APRIL 24–27 LOS ANGELES LOS ANGELES NORDIC WRITERS 2 NORDIC MUSIC TRADE MISSION / NORDIC SOUNDS APRIL 24–27 LOS ANGELES Lxandra Ida Paul Celine Svänback TOPLINER / ARTIST TOPLINER / ARTIST TOPLINER FINLAND FINLAND DENMARK Lxandra is a 21 year-old singer/songwriter from a Ida Paul is a Finnish-American songwriter signed Celine is a new, 22 year-old songwriter from Co- small island called, Suomenlinna, outside of Helsinki, to HMC Publishing (publishing company owned by penhagen, whose discography includes placements Finland. She is currently working on her forthcoming Warner Music Finland) as a songwriter, and Warner with Danish artists such as Stine Bramsen (Copenha- debut album, due out in 2018 on Island Records. Her Records Finland as an artist. She released her de- gen Recs), Noah (Copenhagen Recs), Anya (Sony), first single was “Flicker“, released in 2017. Follow-up but single, “Laukauksia pimeään” in 2016, which Faustix (WB), and Page Four (Sony). Recent collabo- singles included “Hush Hush Baby“ and “Dig Deep”. certified platinum. She has since joined forces with rations include those with Morten Breum (PRMD/Dim popular Finnish artist, Kalle Lindroth, and together Mak/WB), Cisilia (Nexus/Uni), Gulddreng (Uni), and COMPANY they have released three platinum-certified singles Ericka Jane (Uni). Celine is currently collaborating MAG Music/Island Records (“Kupla”, “Hakuammuntaa”, and “Parvekkeella”). with new artists such as Imani Williams (RCA UK), Anna Goller The duo was recently nominated as “Newcomer Jaded (Sony UK), KLOE (Kobalt UK), Polina (Warner Of The Year” for the 2018 Emma Awards (Finn- UK), Leon Arcade (RCA UK), Lionmann (Sony Swe- LINK ish Grammy’s). -

View the Program Guide

AAANSANS AANNUALNNUAL MMEETINGEETITING PPHILADELPHIAHILAHILADELPHIAHIA NEUROSURGERY ON FIRE! PROGRAM GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2010 RECOGNITION 5 INTRODUCTION, AWARDS AND LECTURES 6 SPECIAL EVENTS 24 History Section Dinner, International Reception, NeurosurgeryPAC, Neurosurgical Top Gun Competition, Opening Reception NURSE & PHYSICIAN EXTENDERS’ PROGRAM 25 Advancements in Neurotrauma Care, Endovascular Management of Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Stroke, Mid-Level Practitioner Luncheon RESIDENT, FELLOW AND MEDICAL STUDENT ACTIVITIES 27 Marshal Program, Neurosurgical Top Gun Competition, Young Neurosurgeons Luncheon AANS RESOURCE CENTER 29 AANS Online Career Center, Educational DVDs, Education and Meetings, NREF, Publications, Recorded Presentations, and Silent Auction Bidding Stations SECTION ACTIVITIES 32 AANS AND ANCILLARY MEETINGS 33 AANS COMMERCIAL SUPPORTERS 37 EXHIBITOR INFORMATION 38 Exhibitor Information, Exhibitor Listing—Alphabetical, Exhibitor Listing—by Booth Number, Exhibitor Listing—by Product and Service Category, Floor Plan SATURDAY PROGRAM 68 International Practical Clinics, International Symposium, Practical Clinics SUNDAY PROGRAM 72 Opening Reception, Practical Clinics MONDAY PROGRAM 81 AANS Business Meeting, Breakfast Seminars, Distinguished Service Award, History Section Annual Dinner, Hunt-Wilson Lecture, International Reception, Mid-Level Practitioner Lunch Session, Presidential Address, Richard C. Schneider Lecture, Ronald L. Bittner Lecture, Scientific Sessions, Visit the Exhibit Hall, YNS Lunch Session TUESDAY PROGRAM -

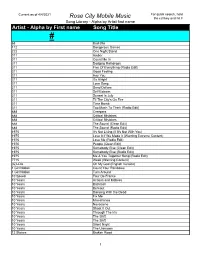

Alpha by First Name Song Title

Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title # 68 Bad Bite 112 Dangerous Games 222 One Night Stand 311 Amber 311 Count Me In 311 Dodging Raindrops 311 Five Of Everything (Radio Edit) 311 Good Feeling 311 Hey You 311 It's Alright 311 Love Song 311 Sand Dollars 311 Self Esteem 311 Sunset In July 311 Til The City's On Fire 311 Time Bomb 311 Too Much To Think (Radio Edit) 888 Creepers 888 Critical Mistakes 888 Critical Mistakes 888 The Sound (Clean Edit) 888 The Sound (Radio Edit) 1975 It's Not Living (If It's Not With You) 1975 Love It If We Made It (Warning Extreme Content) 1975 Love Me (Radio Edit) 1975 People (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Radio Edit) 1975 Me & You Together Song (Radio Edit) 7715 Week (Warning Content) (G)I-Dle Oh My God (English Version) 1 Girl Nation Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation Turn Around 10 Speed Tour De France 10 Years Actions and Motives 10 Years Backlash 10 Years Burnout 10 Years Dancing With the Dead 10 Years Fix Me 10 Years Miscellanea 10 Years Novacaine 10 Years Shoot It Out 10 Years Through The Iris 10 Years The Shift 10 Years The Shift 10 Years Silent Night 10 Years The Unknown 12 Stones Broken Road 1 Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title 12 Stones Bulletproof 12 Stones Psycho 12 Stones We Are One 16 Frames Back Again 16 Second Stare Ballad of Billy Rose 16 Second Stare Bonnie and Clyde 16 Second Stare Gasoline 16 Second Stare The Grinch (Radio Edit ) 1975. -

Honors Proc Ram Not to Disannear

THE OF NORTHERN STATE UNIVERSITY May 1 , 2002 • me 100, Issue 16 • http://science.northern.edu/exponent/index.html Mission Statement Banquet recognizes students, organizations "NSU Student Publications produces a newspaper full of Students attend 15th Annual Student Involvement Awards Banquet local, state and world information. We believe Brandy Schnabel awards of the evening, the organization he students have the right to be Campus Reporter Excellence in Student was there with heard. We believe the truth Involvement award, was also the that evening, should be written. Our motto he events of the 15th very last. This award is given to a Masquers, was is or the students, by the Annual Student senior within one semester of bein ts, with the s ts." Involvement Awards graduating who has recognized as Banquet April 23 went beyond demonstrated community and the the Most Wolves the typical "and the winner is..." campus involvement, leadership, Improved awards ceremony. integrity and a positive attitude. Student bulletin From jokes about a certain This year's winner was Mandy Organization of history professor's height straight Martin, Forsyth, Mont., senior. the Year. His Blanchard from the university president to "It's a great honor to receive exact words appointed as the loud reaction of "ALL this award; it's nice to be were, "Yes...ALL honors director RIGHT!" by one recipient, the recognized for all of the hard RIGHT!" as he Kenneth Blanchard, Jr., professor of night was not without surprises. work," Martin said. sprung from his political science, was recently Awards recipients ranged from Missy Nguyen, Aberdeen, S.D., seat, thrust his appointed as the director of the true freshmen to non-traditional junior, was highlighted twice; fist in the air honors program.