Public Attitudes to the Principles of Sentencing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1989-90 O-Pee-Chee Hockey Card Set Checklist

1 989-90 O-PEE-CHEE HOCKEY CARD SET CHECKLI ST 1 Mario Lemieux 2 Ulf Dahlen 3 Terry Carkner RC 4 Tony McKegney 5 Denis Savard 6 Derek King RC 7 Lanny McDonald 8 John Tonelli 9 Tom Kurvers 10 Dave Archibald 11 Peter Sidorkiewicz RC 12 Esa Tikkanen 13 Dave Barr 14 Brent Sutter 15 Cam Neely 16 Calle Johansson RC 17 Patrick Roy 18 Dale DeGray RC 19 Phil Bourque RC 20 Kevin Dineen 21 Mike Bullard 22 Gary Leeman 23 Greg Stefan 24 Brian Mullen 25 Pierre Turgeon 26 Bob Rouse RC 27 Peter Zezel 28 Jeff Brown 29 Andy Brickley RC 30 Mike Gartner 31 Darren Pang 32 Pat Verbeek 33 Petri Skriko 34 Tom Laidlaw 35 Randy Wood 36 Tom Barrasso 37 John Tucker 38 Andrew McBain 39 David Shaw 40 Reggie Lemelin 41 Dino Ciccarelli 42 Jeff Sharples Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Jari Kurri 44 Murray Craven 45 Cliff Ronning RC 46 Dave Babych 47 Bernie Nicholls 48 Jon Casey RC 49 Al MacInnis 50 Bob Errey RC 51 Glen Wesley 52 Dirk Graham 53 Guy Carbonneau 54 Tomas Sandstrom 55 Rod Langway 56 Patrik Sundstrom 57 Michel Goulet 58 Dave Taylor 59 Phil Housley 60 Pat LaFontaine 61 Kirk McLean RC 62 Ken Linseman 63 Randy Cunneyworth 64 Tony Hrkac 65 Mark Messier 66 Carey Wilson 67 Steve Leach RC 68 Christian Ruuttu 69 Dave Ellett 70 Ray Ferraro 71 Colin Patterson RC 72 Tim Kerr 73 Bob Joyce 74 Doug Gilmour 75 Lee Norwood 76 Dale Hunter 77 Jim Johnson 78 Mike Foligno 79 Al Iafrate 80 Rick Tocchet 81 Greg Hawgood RC 82 Steve Thomas 83 Steve Yzerman 84 Mike McPhee 85 David Volek RC 86 Brian Benning 87 Neal Broten 88 Luc Robitaille 89 Trevor Linden RC Compliments -

Legitimacy and Criminal Justice

LEGITIMACY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE LEGITIMACY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE International Perspectives Tom R. Tyler editor Russell Sage Foundation New York The Russell Sage Foundation The Russell Sage Foundation, one of the oldest of America’s general purpose foundations, was established in 1907 by Mrs. Margaret Olivia Sage for “the improvement of social and living conditions in the United States.” The Foundation seeks to fulfill this mandate by fostering the development and dissemination of knowledge about the country’s political, social, and economic problems. While the Foundation endeav- ors to assure the accuracy and objectivity of each book it publishes, the conclusions and interpretations in Russell Sage Foundation publications are those of the authors and not of the Foundation, its Trustees, or its staff. Publication by Russell Sage, therefore, does not imply Foundation endorsement. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Thomas D. Cook, Chair Kenneth D. Brody Jennifer L. Hochschild Cora B. Marrett Robert E. Denham Kathleen Hall Jamieson Richard H. Thaler Christopher Edley Jr. Melvin J. Konner Eric Wanner John A. Ferejohn Alan B. Krueger Mary C. Waters Larry V. Hedges Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Legitimacy and criminal justice : international perspectives / edited by Tom R. Tyler. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-87154-876-4 (alk. paper) 1. Criminal justice, Administration of. 2. Social policy. 3. Law enforcement. I. Tyler, Tom R. HV7419.L45 2008 364—dc22 2007010929 Copyright © 2007 by Russell Sage Foundation. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of Amer- ica. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

Acadie-Bathurst Titan 68 8 54 5 1 22 141 336

CONTENTS | TABLE DES MATIÈRES PR Contact Information | Coordonnées des relations médias .............................................4 2019 Memorial Cup Schedule | Horaire du tournoi ............................................................5 Competing Teams | Équipes .................................................................................................7 WHL ................................................................................................................................... 11 OHL .................................................................................................................................... 17 QMJHL | LHJMQ ................................................................................................................ 23 Halifax Mooseheads | Mooseheads d'Halifax ................................................................... 29 Rouyn-Noranda Huskies | Huskies de Rouyn-Noranda ..................................................... 59 Guelph Storm | Storm de Guelph ...................................................................................... 89 Prince Albert Raiders | Raiders de Prince Albert .............................................................. 121 History of the Memorial Cup | L’Histoire de la Coupe Memorial .................................... 150 Memorial Cup Championship Rosters | Listes de championnat...................................... 152 All-Star Teams | Équipes D’étoiles ................................................................................... 160 -

1991-92 Pro Set Platinum Hockey 300 Cards Plus 20 Insert Cards RC = Rookie Card

1991-92 Pro Set Platinum Hockey 300 cards plus 20 insert cards RC = Rookie Card Series One Boston Bruins Hartford Whalers Philadelphia Flyers Washington Capitals 1 Cam Neely 42 Rob Brown 85 Mike Ricci 127 Kevin Hatcher 2 Ray Bourque 43 Bobby Holik 86 Steve Duchesne 128 Mike Ridley 3 Craig Janney 44 Pat Verbeek 87 Ron Hextall 129 John Druce 4 Andy Moog 45 Brad Shaw 88 Rick Tocchet 130 Al Iafrate 5 Dave Poulin 46 Kevin Dineen 89 Pelle Eklund 131 Dino Ciccarelli 6 Ken Hodge 47 Zarley Zalapski 90 Rod Brind'Amour 132 Michal Pivonka 7 Glen Wesley Los Angeles Kings Pittsburgh Penguins Winnipeg Jets Buffalo Sabres 48 Jari Kurri 91 Mario Lemieux 133 Fredrik Olausson 8 Dave Andreychuk 49 Tony Granato 92 Jaromir Jagr 134 Ed Olczyk 9 Daren Puppa 50 Luc Robitaille 93 Kevin Stevens 135 Bob Essensa 10 Pierre Turgeon 51 Rob Blake 94 Paul Coffey 136 Pat Elynuik 11 Dale Hawerchuk 52 Wayne Gretzky 95 Ulf Samuelsson 137 Phil Housley 12 Doug Bodger 53 Tomas Sandstrom 96 Tom Barrasso 138 Thomas Steen 13 Mike Ramsey 54 Kelly Hrudey 97 Mark Recchi 139 Don Beaupre 14 Alexander Mogilny Minnesota North Stars Quebec Nordiques 1990-91 Highlights Calgary Flames 55 Mike Modano 98 Ron Tugnutt 140 Bruins 15 Sergei Makarov 56 Jon Casey 99 Mats Sundin 141 Blackhawks 16 Theoren Fleury 57 Todd Elik 100 Stephane Morin 142 Kings 17 Joel Otto 58 Mark Tinordi 101 Owen Nolan 143 North Stars 18 Joe Nieuwendyk 59 Brian Bellows 102 Joe Sakic 144 Penguins 19 Al MacInnis 60 Dave Gagner 103 Bryan Fogarty 20 Gary Suter Original Six Uniforms 21 Mike Vernon Montreal Canadiens San Jose Sharks 145 Bruins 61 Patrick Roy 104 Kelly Kisio 146 Blackhawks Chicago Blackhawks 62 Russ Courtnall 105 Tony Hrkac 147 Red Wings 22 John Tonelli 63 Guy Carbonneau 106 Brian Mullen 148 Canadiens 23 Dirk Graham 64 Denis Savard 107 Doug Wilson 149 Rangers 24 Jeremy Roenick 65 Petr Svoboda 150 Maple Leafs 25 Chris Chelios 66 Kirk Muller St. -

NHL94 Manual for Gens

• BASKETBALL • FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • BASKETBALL • FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • BASKETBALL • FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • HOCKEY • • HOCKEY • GOLF BASEBALL • HOCKEY • FOOTBALL • BASKETBALL • GOLF BASEBALL • HOCKEY FOOTBALL BYLINE USA Ron Barr, sports anchor, EA SPORTS Emmy Award-winning reporter Ron Barr brings over 20 years of professional sportscasting experience to EA SPORTS. His network radio and television credits include play-by play and color commentary for the NBA, NFL and the Olympic Games. In addition to covering EA SPORTS sporting events, Ron hosts Sports Byline USA, the premiere sports talk radio show broadcast over 100 U.S. stations and around the world on Armed Forces Radio Network and* Radio New Zealand. Barr’s unmatched sports knowledge and enthusiasm afford sports fans everywhere the chance to really get to know their heroes, talk to them directly, and discuss their views in a national forum. ® Tune in to SPORTS BYLINE USA LISTENfor IN! the ELECTRONIC ARTS SPORTS TRIVIA CONTEST for a chance to win a free EA SPORTS game. Check local radio listings. 10:00 p.m. to 1:00 a.m. E.T. 9:00 p.m. to 12:00 a.m. C.T. 8:00 p.m. to 11:00 p.m. M.T. 7:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. P.T. OFFICIAL 722805 SEAL OF FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • BASKETBALL • FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • HOCKEY • HOCKEY • GOLF BASEBALL • HOCKEY • FOOTBALL • BASKETBALL • GOLF BASEBALL • HOCKEY FOOTBALL QUALITY • BASKETBALL • FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • BASKETBALL ABOUT THE MAN: Mark Lesser NHL HOCKEY ‘94 SEGA EPILEPSY WARNING PLEASE READ BEFORE USING YOUR SEGA VIDEO GAME SYSTEM OR ALLOWING YOUR CHILDREN TO USE THE SYSTEM A very small percentage of people have a condition that causes them to experience an epileptic seizure or altered consciousness when exposed to certain light patterns or flashing lights, including those that appear on a television screen and while playing games. -

2019-20 Philadelphia Flyers Directory

2019-20 PHILADELPHIA FLYERS DIRECTORY PHILADELPHIA FLYERS Wells Fargo Center | 3601 South Broad Street | Philadelphia, PA 19148 Phone 215-465-4500 | PR FAX 215-218-7837 | www.philadelphiaflyers.com EXECUTIVE MANAGEMENT Chairman/CEO, Comcast-Spectacor .....................................................................................................................................Dave Scott President, Hockey Operations & General Manager ....................................................................................................... Chuck Fletcher President, Business Operations ..................................................................................................................................... Valerie Camillo Governor ..................................................................................................................................................................................Dave Scott Alternate Governors ....................................................................................................Valerie Camillo, Chuck Fletcher, Phil Weinberg Senior Advisors ........................................................................................................................Bill Barber, Bob Clarke, Paul Holmgren Executive Assistants ............................................................................................. Janine Gussin, Frani Scheidly, Tammi Zlatkowski HOCKEY CLUB PERSONNEL Vice President/Assistant General Manager ..........................................................................................................................Brent -

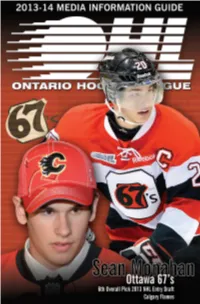

2013-14 OHL Information Guide.Pdf

Contents Ontario Hockey League Awards and Trophies Ontario Hockey League Directory 4 Team Trophies 128 History of the OHL 6 Individual Trophies 131 Canadian Hockey League Awards 142 Member Teams OHL Graduates in the Hall of Fame 143 Barrie Colts 8 Belleville Bulls 11 All-Star Teams Erie Otters 14 All-Star Teams 144 Guelph Storm 17 All-Rookie Teams 149 Kingston Frontenacs 20 Kitchener Rangers 23 2013 OHL Playoffs London Knights 26 Robertson Cup 152 Mississauga Steelheads 29 OHL Championship Rosters 153 Niagara IceDogs 32 Playoff Records 156 North Bay Battalion 35 Results 157 Oshawa Generals 38 Playoff Scoring Leaders 158 Ottawa 67’s 41 Goaltender Statistics 160 Owen Sound Attack 44 Player Statistics 161 Peterborough Petes 47 2013 OHL Champions photo 166 Plymouth Whalers 50 Saginaw Spirit 53 Memorial Cup Sarnia Sting 56 History 167 Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds 59 All-Star Teams 168 Sudbury Wolves 62 Trophies 169 Windsor Spitfires 65 Records 170 Officiating Staff Directory 68 Ontario teams to win the Memorial Cup 172 2012-13 Season in Review NHL Entry Draft Team Standings 69 Results of the 2013 NHL Entry Draft 174 Scoring Leaders 69 OHL Honour Roll 176 Goaltending Leaders 71 Coaches Poll 72 All-Time Coaching Leaders 178 Goaltender Statistics 73 Player Statistics 75 Media Directory Historical Season Results 84 OHL Media Policies 179 OHL Media Contacts 180 Records Media covering the OHL 181 Team Records 120 Individual Records 124 2013-14 OHL Schedule 182 The 2013-14 Ontario Hockey League Information Guide and Player Register is published by the Ontario Hockey League. -

2020 Draft Guide

CONTENTS 2 ........................................ Draft Information, First Round Order, Avalanche 2020 Draft Picks 3 ................................................................................................. A Look Back: The No. 25 Pick 4 .............................................................................................Current Roster By Draft Position 5 .............................................................................................................Avs in the First Round 6 ................................................................................................All-Time Draft Picks By Round 9 ................................................................................................... All-Time Draft Picks By Year 12 .............................................................................................All-Time Draft Picks By League 16 ........................................................................................... All-Time Draft Picks By Position 19 ...................................................................................All-Time Draft Picks By Birth Country 21 ........................................................................................ Avalanche Drafts By the Numbers 22 ................................................................................... 2020 NHL Central Scouting Rankings AVALANCHE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Jean Martineau | Senior V.P. of Communications & Team Services | [email protected] | (303) 405-6005 Brendan McNicholas -

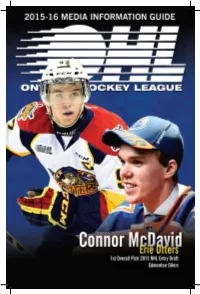

2015-16 OHL Information Guide

15-16 OHL Guide Ad-Print.pdf 1 7/30/2015 2:02:27 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 15-16 OHL Guide Ad-Print.pdf 1 7/30/2015 2:02:27 PM Contents Ontario Hockey League Awards and Trophies Ontario Hockey League Directory 4 Team Trophies 128 History of the OHL 6 Individual Trophies 131 Canadian Hockey League Awards 142 Member Teams OHL Graduates in the Hall of Fame 143 Barrie Colts 8 Erie Otters 11 All-Star Teams Flint Firebirds 14 All-Star Teams 144 Guelph Storm 17 All-Rookie Teams 149 Hamilton Bulldogs 20 Kingston Frontenacs 23 2015 OHL Playoffs Kitchener Rangers 26 Robertson Cup 152 London Knights 29 OHL Championship Rosters 153 Mississauga Steelheads 32 Playoff Records 156 Niagara IceDogs 35 Results 157 North Bay Battalion 38 Playoff Scoring Leaders 158 Oshawa Generals 41 Goaltender Statistics 160 Ottawa 67’s 44 Player Statistics 161 Owen Sound Attack 47 2015 OHL Champions photo 166 C Peterborough Petes 50 M Saginaw Spirit 53 Memorial Cup Sarnia Sting 56 History 167 Y Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds 59 All-Star Teams 168 CM Sudbury Wolves 62 Trophies 169 Windsor Spitfires 65 Records 170 MY Ontario teams to win the Memorial Cup 172 CY Officiating Staff Directory 68 NHL Draft CMY 2014-15 Season in Review Results of the 2015 NHL Draft 174 K Team Standings 69 OHL Honour Roll 176 Scoring Leaders 69 Goaltending Leaders 71 All-Time Coaching Leaders 178 Coaches Poll 72 Goaltender Statistics 73 Media Directory Player Statistics 75 OHL Media Policies 179 Historical Season Results 84 OHL Media Contacts 180 Media covering the OHL 181 Records Team Records 120 2015-16 OHL Schedule 182 Individual Records 124 The 2015-16 Ontario Hockey League Information Guide and Player Register is published by the Ontario Hockey League. -

Hockey Collection 2012

Base Set (400): 1-9, 11, 13-15, 17-32, 34, 37, 39-40, 42-50, HOCKEY CARD CATALOGUE 52-55, 57-58, 60-70, 72-76, 78-84, 87, 90-91, 93-96, Updated: April 20, 2012 – Unverified in Yellow Highlight 99-102, 104-113, 115-120, 122-129, 131-133, 135, 137, 139-141, 143-150, 152-159, 161, 164-168, 170, 173-176, 178, 180-187, 189-190, 192-196, 200, 202-203, 205-209, NORTH AMERICAN RELEASES 211-214, 216-221, 223-227, 230-235, 238-240, 243, 245-250, 254-259, 263-270, 272, 274-278, 281-285, 288, ARENA HOLOGRAMS 290-292, 294-296, 299-300, 303, 308, 313-314, 316-317, 1991 319-330, 332-344, 346-351, 355-367, 369-382, 384, 387, • Base Set (33): 1-33 393-395, 400 • Pat Falloon Hologram (1): 1 First Round Draft Pick – Hobby (25; Cards No. 401-425): Autographs (33): 12 Marcus Naslund; 22 Jassen Cullimore; 401-402, 409-413, 423-425 25 Andrew Verner First Round Draft Pick – Retail (25; Cards No. 401-425): 405, 408, 411, 419-421 BE A PLAYER / IN THE GAME – BETWEEN THE PIPES Game Used Jerseys (160): 53 Miroslav Satan; 2001-2002 Between The Pipes (Be A Player) 138 Jose Theodore Base Set (170): 1, 3-16, 18-36, 38-39, 41-42, 48-54, 56-64, 67-70, 72-83, 85-93, 95-128, 130-152, 156, 159, BE A PLAYER – MEMORABILIA SERIES 161-162, 164, 166, 168, 170 1999-2000 BAP Memorabilia Series NOTE: Cards no. -

Colorado Avalanche Roster 2019-20 Active Roster

2019-20 COLORADO AVALANCHE ERIK JOHNSON KEVIN CONNAUTON CALE MAKAR MATT CALVERT VALERI NICHUSHKIN NIKITA ZADOROV #6 DEFENSEMAN #7 DEFENSEMAN #8 DEFENSEMAN #11 LEFT WING #13 RIGHT WING #16 DEFENSEMAN TYSON JOST COLIN WILSON RYAN GRAVES IAN COLE NATHAN MacKINNON PHILIPP GRUBAUER #17 CENTER #22 CENTER #27 DEFENSEMAN #28 DEFENSEMAN #29 CENTER #31 GOALTENDER MICHAEL HUTCHINSON J.T. COMPHER PAVEL FRANCOUZ PIERRE-EDOUARD BELLEMARE MARK BARBERIO SAMUEL GIRARD #35 GOALTENDER #37 LEFT WING #39 GOALTENDER #41 CENTER #44 DEFENSEMAN #49 DEFENSEMAN JOONAS DONSKOI VLADISLAV KAMENEV MATT NIETO VLADISLAV NAMESTNIKOV NAZEM KADRI GABRIEL LANDESKOG #72 RIGHT WING #81 CENTER #83 LEFT WING #90 CENTER #91 CENTER #92 LEFT WING ANDRE BURAKOVSKY MIKKO RANTANEN #95 LEFT WING #96 RIGHT WING JARED BEDNAR RAY BENNETT NOLAN PRATT JUSSI PARKKILA BRETT HEIMLICH HEAD COACH ASSISTANT COACH ASSISTANT COACH GOALTENDING COACH VIDEO COACH COLORADO AVALANCHE HOCKEY CLUB Pepsi Center, 1000 Chopper Circle, Denver, Colorado, 80204 | (303) 405-1100 main | (303) 893-0614 fax | www.ColoradoAvalanche.com EXECUTIVE STAFF Owner/Chairman, Kroenke Sports & Entertainment, LLC ........................................................................................................................ E. Stanley Kroenke President & Governor, Avalanche & Vice Chairman, Kroenke Sports & Entertainment, LLC ............................................................................... Josh Kroenke Executive Vice President/General Manager/Alternate Governor .............................................................................................................................Joe -

1989 SC Playoff Summaries

MONTRÉAL CANADIENS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 1 9 9 3 Jesse Belanger, Brian Bellows, Patrice Brisebois, Benoit Brunet, Guy Carbonneau CAPTAIN, J.J. Daigneault, Vincent Damphousse, Eric Desjardins, Gilbert Dionne, Paul DiPietro, Donald Dufresne, Todd Ewen, Kevin Haller, Sean Hill, Mike Keane, Stephan Lebeau, John LeClair, Gary Leeman, Kirk Muller, Lyle Odelein, Andre Racicot, Rob Ramage, Mario Roberge, Ed Ronan, Patrick Roy, Denis Savard, Mathieu Schneider Ronald Corey PRESIDENT, Serge Savard GENERAL MANAGER Jacques Demers HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 1993 ADAMS DIVISION SEMI-FINAL 1 BOSTON BRUINS 109 v. 4 BUFFALO SABRES 86 GM HARRY SINDEN, HC BRIAN SUTTER v. GM GERRY MEEHAN, HC JOHN MUCKLER SABRES SWEEP SERIES Sunday, April 18 Tuesday, April 20 BUFFALO 5 @ BOSTON 4 OVERTIME BUFFALO 4 @ BOSTON 0 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. BUFFALO, Dave Hannan 1 (unassisted) 2:32 1. BUFFALO, Wayne Presley 1 (unassisted) 4:27 SHG GWG 2. BUFFALO, Pat LaFontaine 1 (Alexander Mogilny) 9:26 2. BUFFALO, Randy Wood 1 (Bill Houlder, Bob Sweeney) 8:07 PPG Penalties — Mogilny Bu 0:26, Wiemer Bo 3:36, Errey Bu 7:29, Shaw Bo 8:58, Neely Bo 12:31, Wood Bu 15:04, Penalties — Roberts Bo B.