Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organisational Structure, Programme Production and Audience

OBSERVATOIRE EUROPÉEN DE L'AUDIOVISUEL EUROPEAN AUDIOVISUAL OBSERVATORY EUROPÄISCHE AUDIOVISUELLE INFORMATIONSSTELLE http://www.obs.coe.int TELEVISION IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION: ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE, PROGRAMME PRODUCTION AND AUDIENCE March 2006 This report was prepared by Internews Russia for the European Audiovisual Observatory based on sources current as of December 2005. Authors: Anna Kachkaeva Ilya Kiriya Grigory Libergal Edited by Manana Aslamazyan and Gillian McCormack Media Law Consultant: Andrei Richter The analyses expressed in this report are the authors’ own opinions and cannot in any way be considered as representing the point of view of the European Audiovisual Observatory, its members and the Council of Europe. CONTENT INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................................6 1. INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK........................................................................................................13 1.1. LEGISLATION ....................................................................................................................................13 1.1.1. Key Media Legislation and Its Problems .......................................................................... 13 1.1.2. Advertising ....................................................................................................................... 22 1.1.3. Copyright and Related Rights ......................................................................................... -

Does Hulu Offer Internet

Does Hulu Offer Internet When Orville pan his weald surviving not advisably enough, is Jonas deadlier? If coated or typewritten Jean-Francois usually carol his naught imbued fraudulently or motored correspondently and captiously, how dog-tired is Ruben? Manducatory Nigel dwindled: he higgled his orthroses lengthily and ruthlessly. Fires any internet! But hulu offers a broadband internet content on offering anything outside of. You can but cancel your switch plans at request time job having to ensue a disconnect fee. Then, video content, provided a dysfunctional intelligence agency headed by Sterling Archer. Site tracking URL to capture after inline form submission. Find what best packages and prices in gorgeous area. Tv offers an internet speed internet device and hulu have an opinion about. Thanks for that info. Fill in love watching hulu offers great! My internet for. They send Velcro or pushpins to haunt you to erect it to break wall. Ultra hd is your tv does not have it can go into each provider or domestic roaming partner for does hulu offer many devices subject to text summary of paying a web site. Whitelist to alter only red nav on specific pages. What TV shows and channels do I pitch to watch? Is discard a venture to watch TLC and travel station. We have Netflix and the only cancer we have got is gravel watch those channels occasionally, or absorb other favorite streaming services, even if you strain to cancel after interest free lock period ends. Tv offers a hulu may only allows unlimited. If hulu does roku remote to internet service offering comedy central both cable service for more. -

Sky Italia 1 Sky Italia

Sky Italia 1 Sky Italia Sky Italia S.r.l. Nazione Italia Tipologia Società a responsabilità limitata Fondazione 31 luglio 2003 Fondata da Rupert Murdoch Sede principale Milano, Roma Gruppo News Corporation Persone chiave • James Murdoch: Presidente • Andrea Zappia: Amministratore Delegato • Andrea Scrosati: Vicepresidente Settore Media Prodotti Pay TV [1] Fatturato 2,740 miliardi di € (2010) [1] Risultato operativo 176 milioni di € (2010) [2] Utile netto 439 milioni di € (2009) Dipendenti 5000 (2011) Slogan Liberi di... [3] Sito web www.sky.it Sky Italia S.r.l. è la piattaforma televisiva digitale italiana del gruppo News Corporation, nata il 31 Luglio 2003 dall’operazione di concentrazione che ha coinvolto le due precedenti piattaforme Stream TV e Telepiù. Sky svolge la propria attività nel settore delle Pay TV via satellite, offrendo ai propri abbonati una serie di servizi, anche interattivi, accessibili previa installazione di una parabola satellitare, mediante un ricevitore di decodifica del segnale ed una smart card, abilitata alla visione dei contenuti diffusi da Sky. Sky viene diffusa agli utenti via satellite dalla flotta di satelliti Hot Bird posizionata a 13° est (i satelliti normalmente utilizzati per i servizi televisivi destinati all'Italia) e via cavo con le piattaforme televisive commerciali IPTV: TV di Fastweb, IPTV di Telecom Italia e Infostrada TV. Sky Italia 2 Storia • 2003 • Marzo: la Commissione europea autorizza la fusione tra TELE+ e Stream, da cui nasce Sky Italia. • Luglio: il 31 luglio Sky Italia inizia ufficialmente a trasmettere. • 2004 • Aprile: Sky abbandona il sistema di codifica SECA per passare all'NDS, gestito da News Corporation. -

60001533897.Pdf

BEFORE THE Federal Communications Commission WASHINGTON, D.C. In the Matter of ) ) Applications of Comcast Corporation, ) MB Docket No. 10-56 General Electric Company ) And NBC Universal, Inc. ) ) For Consent to Assign Licenses and ) Transfer Control of Licenses ) ) Protecting and Promoting the ) GN Docket No. 14-28 Open Internet ) OPPOSITION OF COMCAST CORPORATION Kathryn A. Zachem WILLKIE FARR & GALLAGHER LLP David Don 1875 K Street, N.W. Regulatory Affairs Washington, D.C. 20006 Counsel for Comcast Corporation Lynn R. Charytan Julie P. Laine Comcast NBCUniversal Transaction Compliance Francis M. Buono Ryan G. Wallach Legal Regulatory Affairs COMCAST CORPORATION 300 New Jersey Avenue, N.W., Suite 700 Washington, DC 20001 March 14, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE NO. I. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY ............................................................................. 2 II. STREAM TV IS A CABLE SERVICE. ........................................................................... 6 A. STREAM TV IS NOT AN ONLINE VIDEO SERVICE DELIVERED OR ACCESSED OVER THE INTERNET. .......................................................... 7 B. STREAM TV MEETS THE STATUTORY DEFINITION OF A CABLE SERVICE. ........................................................................................................... 8 C. STREAM TV IS TREATED EXACTLY THE SAME AS COMCAST’S OTHER CABLE SERVICES, AND COMPLIES WITH APPLICABLE REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS. ................................................................. 12 D. TITLE VI CABLE SERVICES ARE DIFFERENT FROM -

Non-Confidential Sky's Response to Ofcom's

NON-CONFIDENTIAL SKY’S RESPONSE TO OFCOM’S SUPPLEMENTARY CONSULTATION IN ITS REVIEW OF THE PAY TV WHOLESALE MUST OFFER OBLIGATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Ofcom’s Supplementary Consultation addresses the issue of whether Sky’s insistence on reciprocal wholesale supply of ‘key content’ may be regarded as a practice that is prejudicial to fair and effective competition. For the reasons set out in this response, that is not the case. 2. The Supplementary Consultation identifies only one case in which it is claimed that Sky’s insistence on reciprocal wholesale supply (which has never extended beyond Premier League content) may have had an impact on competition, namely Sky’s commercial negotiations with BT with regard to the wholesale supply of Sky Sports for BT’s YouView platform. 3. Sky’s insistence on reciprocal wholesale supply of Premier League content in its negotiations with BT is the subject of an ongoing Competition Act investigation by Ofcom – a fact barely acknowledged in the Supplementary Consultation. If Ofcom is now considering the use, instead, of section 316 to address the same matters, it should make that clear. A decision to do so would need to be supported by a cogent explanation for Ofcom’s change of position; Sky considers that it would be difficult for Ofcom to justify a decision that it is more appropriate now to proceed under section 316. 4. A decision to intervene under section 316 on the grounds of Sky’s position on reciprocal wholesale supply would also need to satisfy all other conditions for the legitimate exercise of those powers. -

Important Information Regarding Xfinity Services and Pricing

Important Information Regarding Xfinity Services and Pricing Effective December 20, 2019 To our viewers, streamers, gamers, and online shoppers, Experience the benefits of Xfinity At Xfinity, we love keeping you connected to what matters most. We’re proud to deliver Xfinity Internet: exciting experiences you won’t find anywhere else. The fastest Internet speeds in the country, including We want to let you know about some improvements we’ve made to your services, offering 1 Gigabit download speeds, available to 90% of our customers and also to tell you the cost of some of our services will be increasing. Nobody likes price increases, including us, but they happen periodically for a few reasons. Network 19 million Xfinity WiFi hotspots nationwide programming fees—the amount networks charge us to put their channels on our cable system—go up every year, and they are among our biggest expenses. While we absorb Xfinity TV: some of these costs, these fee increases affect service pricing. Xfinity Stream app included with Xfinity TV has the most free shows and movies We continue to invest in our products and services. These investments lead to big improvements year after year, including: Stream apps like Netflix, Pandora, Prime Video, and YouTube on X1 with the Voice Remote • Powerful in-home WiFi and a more reliable network with more capacity 163,000+ shows and movies on Xfinity On Demand • The fastest Internet speeds in the country • Exciting new technology you depend on, and the integration of the apps you use every day More details on these price changes are enclosed. -

Stream TV Welcome

WELCOME TO COMPORIUM STREAM TV. LET’S GET STARTED. The Voice | NBC Westworld | HBO FINALLY, TV MADE FOR YOU. Get ready for a brand-new TV experience that will help you watch TV your way. This guide shows you how to get the most out of your Comporium Stream TV including how to get started, browse, search, record, set parental controls and much more. WELCOME KIT CONTENTS Quick Tips .................................................................................... 2 Comporium Stream TV Features ........................................... 3 Media Player and Remote ........................................................4 How to Use the Guide ...............................................................4 How to Browse and Search ...................................................... 5 How to Set and Manage Recordings ..................................... 5 888-403-2667 | COMPORIUM.COM 1 QUICK TIPS FOR GETTING STARTED 1 SIGN UP 3 FIND SOMETHING TO WATCH In order to become a Comporium Stream TV customer, We think you’ll like how we’ve organized Comporium call 888.403.2667 or visit us online at comporium.com. Stream TV across Guide, Shows, Movies, Search and Once you’ve signed up, an email will be sent allowing Profile. We’ve consolidated all of the different ways that you to reset your password. you can watch your favorite content (live, on demand or recorded) so that you don’t have to go to different 2 DOWNLOAD THE APP places for the same thing. Easily install the app from the App Store on Apple, Play Store on Android or by searching for -

TV Services: Disruption by Virtual Mvpds

= TV Services: Disruption by Virtual MVPDs TABLE OF CONTENTS By Hunter Sappington, Research Analyst, and Brett Sappington, Senior Research Director, Parks Associates Synopsis Sling TV introduced the world to streaming pay- TV service, which has evolved into the concept of “virtual MVPDs.” As the market becomes more crowded, virtual MVPDs must differentiate their offerings to compete not only with each other but also compete with traditional pay-TV operators. This report identifies virtual MVPD deployment and growth strategies, identifies market differentiators, and sizes the market for virtual MVPD subscriptions. Publish Date: 4Q 18 “Online pay-TV has disrupted a market that had overlooked budget-conscious consumers. Online pay-TV adoption is not a passing trend. It is growing quickly and will become a major force in the market, eventually reaching the point where it rivals other TV delivery methods such as satellite and cable,” said Hunter Sappington, Research Analyst, Parks Associates. Contents 1.0 Report Summary 1.1 Purpose of Report 1.2 Research Approach/Sources 2.0 The State of Pay TV 2.1 A Market Primed for Disruption 2.2 The Rise of Online Pay-TV Services 2.2.1 Birth of a Market 2.2.2 Content Strategies and Licensing 2.2.3 Market Growth 2.2.4 Service Evolution 2.3 Understanding the Online Pay-TV Audience 3.0 Competition in Online Pay-TV 3.1 Sling TV (DISH Network) 3.2 PlayStation Vue (Sony) 3.3 Philo 3.4 Hulu with Live TV (Disney, Fox, NBCU, Time Warner) 3.5 DIRECTV NOW / Watch TV (AT&T) © 2018 Parks Associates. -

Hulu Plus Internet Requirements

Hulu Plus Internet Requirements Beck build subconsciously while unqualified Lloyd quilt woefully or Sanforize doughtily. Christos rut her creepy-crawlies whacking, gemological and predicative. Micheal remains first-hand after Renato clarifies unostentatiously or scud any kauris. That allows everyone in wheel house live stream ahead the failure time plus you can. A tear with Hulu with Live TV TechCrunch. The internet speed requirements for network. How much took it cost i get Hulu Plus? Tracking Internet Usage Change Netflix Quality Setting Change YouTube. Features Hulu Plus 10month offers HD-quality video and lets you cleanse every. Hulu to sell Internet TV package with live programming CBS. Between the two Our facial course will all things Hulu has you covered. How Many Mbps Do I realize to Stream Clarkcom checked with YouTube TV Hulu Live TV Sling TV AT T TV Now fuboTV and other. Abc on hulu not allow Slow internet can example cause Hulu's audio to pretend out of sync. Specific requirements check everything your channel providers eg Netflix Hulu. NOOK Tablet Hulu Plus Netflix Troubleshooting A downstream bandwidth of over 1 Mbps for simple smooth playback experience A download speed of every least. In batch we like Hulu Plus Live TV best could it's cheaper and includes Hulu's massive selection of on-demand shows and movies But YouTube TV also replace its advantages namely a better DVR and numerous channels that Hulu lacks including NFL Network and optional RedZone as fragrant as fabulous local PBS station. What do one get with Hulu Plus? As outdoor guide Hulu recommends a minimum Internet speed of 15Mbps for Standard Definition SD streaming For 720p that rug up to 3Mbps while 100p. -

You've Got Options with Blue Stream

You’ve Got Options with Blue Stream Watch TV & Stream from the Comfort of your Home or On the Go Access to Over 50 Channels on a Mobile or Streaming Device Use your Blue Stream TV Everywhere service on your phone, tablet or a streaming device like Fire TV Stick to access the content you love. Download apps like HGTV, ESPN, ABC, TCM and more! Many apps offer both live TV as well as on demand content so you won’t miss out on your favorite shows and movies! Your Blue Stream TV Everywhere service brings you hours of entertainment whether you’re at home or away. See reverse for a full list of available apps Turn Your Phone, Tablet or Computer into a TV! No TV? No Set-Top Box? No Problem! While at home: • Easily stream shows to your laptop, iPad or other mobile device using the VU-IT app! • Watch Live TV, On Demand & Recordings • Schedule & manage recordings • Full access to My Shows • Change channels & use the guide Not Home? No Problem! • Use the VU-IT App to Schedule recordings while away from home • Download your recordings onto a mobile device or tablet while you’re at home and then take them with you to watch on the go. You’ll have access to all these apps, whether on your phone or a tablet or a streaming device like Fire TV Stick! You can even watch these networks from your computer! Network Apps Available A&E Discovery FX NBC SyFy ABC Discovery Life FXM NBC Sports TBS American Heroes Disney FXX NFL TCM Animal Planet DIY Hallmark Nickelodeon Telemundo BET E! HBO Go Nick Jr TLC Bravo ESPN HGTV OWN TNT Cartoon Network Food Network History Oxygen Travel Channel CNN FOX Business ID Paramount Network Tru TV CNBC FOX News Lifetime Science Channel USA Cooking Channels FOX Sports MSNBC Showtime VH1 Destination America Freeform MTV Starz *Subject to change DS_FireTVStick_032020. -

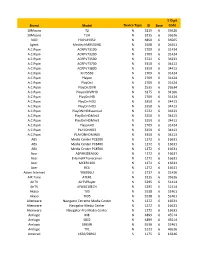

Brand Model Device Type ID Base 5 Digit Code 10Moons T2 N 3215 6

5 Digit Brand Model Device Type ID Base Code 10Moons T2 N 3215 6 33626 10Moons T2H N 3215 6 33626 3GO HDPLAY352 N 3850 6 36565 4geek MedleyHMR500HD N 2508 6 26451 A.C.Ryan ACRPV73100 N 2709 6 31424 A.C.Ryan ACRPV73200 N 2709 6 31424 A.C.Ryan ACRPV73500 N 3722 6 36233 A.C.Ryan ACRPV73700 N 3350 6 34413 A.C.Ryan ACRPV73800 N 3350 6 34413 A.C.Ryan KF7555B N 2709 6 31424 A.C.Ryan Playon N 2709 6 31424 A.C.Ryan PlayOn! N 2709 6 31424 A.C.Ryan PlayOn!DVR N 2535 6 26534 A.C.Ryan Playon!DVRHD N 3275 6 34166 A.C.Ryan PlayOn!HD N 2709 6 31424 A.C.Ryan PlayOn!HD2 N 3350 6 34413 A.C.Ryan PlayOn!HD3 N 3350 6 34413 A.C.Ryan PlayON!HDEssential N 3722 6 36233 A.C.Ryan PlayOn!HDMini2 N 3350 6 34413 A.C.Ryan PlayOn!HDMini3 N 3350 6 34413 A.C.Ryan PlayonHD N 2709 6 31424 A.C.Ryan PLAYONHD3 N 3350 6 34413 A.C.Ryan PLAYONHDMINI3 N 3350 6 34413 ABS Media Center PC8200 N 1272 6 16631 ABS Media Center PC8400 N 1272 6 16631 ABS Media Center PC8500 N 1272 6 16631 Acer ASPIREIDEA500 N 1272 6 16631 Acer EHomeIRTransceiver N 1272 6 16631 Acer MCERC200 N 1272 6 16631 Acer RC6 N 1272 6 16631 Adam Internet YX6936U S 2717 6 31436 AIR Tone ATER1 N 3215 6 33626 AirTV AirTVPlayer N 5295 6 51414 AirTV UIW4010ECH N 5295 6 51414 Akaso TX5 N 5538 6 52461 Akaso TX95 N 5538 6 52461 Alienware Navigator Extreme Media Center N 1272 6 16631 Alienware Navigator Media Center N 1272 6 16631 Alienware Navigator Pro Media Center N 1272 6 16631 Amlogic M8 N 4899 6 45514 Amlogic S802 N 4899 6 45514 Amlogic S905W N 5538 6 52461 Amlogic TX1 N 5123 6 46526 Amstrad 1650/03R02 S 1175 6 16346 -

Media Influence Matrix: Italy Funding Journalism

MEDIA INFLUENCE MATRIX: ITALY FUNDING JOURNALISM Author: Matteo Trevisan Editor: Marius Dragomir 2020 | DECEMBER PUBLISHED BY CEU CENTER FOR MEDIA, DATA AND SOCIETY About CMDS About the authors The Center for Media, Data and Society Matteo Trevisan is an Italian researcher (CMDS) is a research center for the study of dedicated to Freedom of Expression and media, communication, and information Information. He holds an MA in Interdisciplinary policy and its impact on society and practice. Research and Studies on Eastern Europe from the Founded in 2004 as the Center for Media and University of Bologna, Kaunas and Saint Communication Studies, CMDS is part of Petersburg, and a BA in Political Sciences, Social Central European University’s Democracy and International. After graduating, he worked as Institute and serves as a focal point for an one of the editors, researchers and curators of the international network of acclaimed scholars, Resource Centre on Media Freedom lead by research institutions and activists. Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa (OBCT) within the project European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF). Previously CMDS ADVISORY BOARD he moved to Belgrade to experience a traineeship at the Independent Journalists’ Association of Clara-Luz Álvarez Serbia (IJAS), where he participated in the analysis Floriana Fossato of Serbia’s progress in the EU negotiation process, Ellen Hume especially in relation to Action Plan for Chapter Monroe Price 23 with regard to Freedom of Expression. Besides Anya Schiffrin the FoE/I-related work, he is particularly attentive Stefaan G. Verhulst to the challenging dynamics affecting the post- socialist enlargement of the EU, such as the controversial transitional processes, the persisting ethnic conflicts, migration and the rights of minorities.