The Manufacture and Trade of Luxury Textiles in the Age of Mercantilism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Employment and Economic Growth

Health Employment An Evidence Base Health Employment and Economic Growth Powerful demographic and economic forces are shaping health The 17 chapters and Economic Growth workforce needs and demands worldwide. in this book, are grouped into Effectively addressing current and future health workforce four parts: An Evidence Base needs and demands stands as one of our foremost challenges. It also represents an opportunity to secure a future that is • Health workforce healthy, peaceful, and prosperous. dynamics The contents of this book give direction and detail to a richer • Economic value Edited by and more holistic understanding of the health workforce and investment James Buchan through the presentation of new evidence and solutions- focused analysis. It sets out, under one cover, a series of • Education and Ibadat S. Dhillon research studies and papers that were commissioned to production provide evidence for the High-Level Commission on Health James Campbell Employment and Economic Growth. • Addressing inefficiencies ‘’An essential read that rightfully places investments in health workforce at the heart of the SDG Agenda.” — Richard Horton, Editor-in-Chief The Lancet “A resource of fundamental importance. Evidences the socio-economic benefits that follow from appropriately recognizing, rewarding, and supporting women’s Campbell Dhillon Buchan work in health.” — H.R.H. Princess Muna al-Hussein, Princess of Jordan Health Employment and Economic Growth An Evidence Base Edited by James Buchan Ibadat S. Dhillon James Campbell i Health Employment and Economic Growth: An Evidence Base ISBN 978-92-4-151240-4 © World Health Organization 2017 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). -

U.S.-French Commercial Ties

Order Code RL32459 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web U.S.-French Commercial Ties July 7, 2004 Raymond J. Ahearn Specialist in International Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress U.S.-French Commercial Ties Summary U.S. commercial ties with France are extensive, mutually profitable, and growing. With approximately $1 billion in commercial transactions taking place between the two countries every business day of the year, each country has an increasingly large stake in the health and openness of the other’s economy. France is the 9th largest merchandise trading partner for the United States and the United States is France’s largest trading partner outside the European Union. In 2003, 64% or $29.7 billion of bilateral trade occurred in major industries such as aerospace, pharmaceuticals, medical and scientific equipment, electrical machinery, and plastics where both countries export and import similar products. The United States and France also have a large and growing trade in services such as tourism, education, finance, insurance and other professional services. In 2002, France was the sixth largest market for U.S. exports of services and the seventh largest provider of services to the United States. While trade in goods and services receives most of the attention in terms of the commercial relationship, foreign direct investment and the activities of foreign affiliates can be viewed as the backbone of the commercial relationship. The scale of sales of U.S.-owned companies operating in France and French-owned companies operating in the United States outweighs trade transactions by a factor of six to five. -

Download Study

PROFESSOR LAMFALUSSY COMMEMORATIVE CONFERENCE ’HIS CONTRIBUTION TO ECONOMIC POLICY AND THE BIRTH OF THE EURO’ Conference logbook on the third conference of the Magyar Nemzeti Bank’s Lamfalussy Lectures Conference series Budapest, 1 February 2016 Published by: Magyar Nemzeti Bank 9 Szabadság tér, Budapest 1054 Responsible publisher: Marcell Horváth Editor: Anna Ditta Lugosi Cover design: Anna Ditta Lugosi Photos: András Hajnal All studies are paper based on the lecture given at the Conference. Copying, publication or any use of this book in whole or in part (text, chart, picture, etc.), except in cases of free use as established in Hungarian copyright law, shall not be allowed without the preliminary written permission by the Magyar Nemzeti Bank. Printed by: SPL–Prospektus Consortium Budapest, 2016 CONTENTS Foreword by György Matolcsy 5 Lamfalussy Lectures Conference Revisiting Lamfalussy’s insights regarding financial globalisation and the global financial crisis: the need to rebuild confidence Luiz Awazu Pereira da Silva, Deputy General Manager, Bank for International Settlements From the euro to banking union – what can we learn from Sándor Lámfalussy? Ewald Nowotny, Governor, Oesterrishische Nationalbank Time for a new Lamfalussy moment Benoît Cœuré, Member of the Executive Board, European Central Bank Navigating in uncharted waters, Alexandre Lamfalussy, the Euro and a Genuine Economic and Monetary Union Jan Smets, Governor, National Bank of Belgium Greece and The Euro Crisis: Lessons From Confidence Edmond Alphandéry, Former Minister -

Rail Transport, Agrarian Crisis, and the Reorganization of Agriculture: France and Great Britain Confront Globalization, 1860‐1900

Rail Transport, Agrarian Crisis, and the Reorganization of Agriculture: France and Great Britain Confront Globalization, 1860‐1900 Paper presented at the Colloque sur la genèse des marchés, Paris, Hôtel de la Monnaie, May 19, 2008 Robert M. Schwartz In this paper I want to suggest why the British and French governments responded differently to the globalization of agriculture and the prolonged agrarian crisis from 1873 to 1896 that globalization engendered. Part of the great depression in trade, the Agrarian Crisis brought a dramatic reversal in the fortunes of French and British farmers. The arrival on European markets of a growing surplus of agrarian goods, chiefly from the United States and Canada, depressed prices and agricultural incomes, undermining the profitability of large farms in particular and generating political pressure on governments to help protect farm incomes. The origin, character, and geographic extent of the crisis were in many ways determined by the nineteenth‐century transport revolution. Rail transport was perhaps the most important element in that revolution, and its effects on agriculture changed over time and space. The arrival of rail transport in the countryside stimulated economic growth by opening new opportunities for British and French farmers to market their surplus production in regional and national markets. In time, however, rail freight also brought increased competition and depressed agricultural prices. Both effects fostered a spatial reorganization of agriculture and a shift from mixed farming to specialized production. The British government responded to the crisis by continuing a policy of laissez‐faire and open agricultural markets, while allowing railway freight rates to be determined mainly through the competition of private rail companies. -

France As of September 2020

Report Overview (updated as of September 25, 2020) This is an overview of the economy of France as of September 2020. This report will summarize the economic state of France and changes resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Fast Facts/Statistics1 ➢ Population: 67,098,824 ➢ GDP (PPP): $2.86 trillion ➢ GDP per capita: $47,223 (2019) ➢ GDP growth rate: -7.2% ➢ Projected GDP growth rate: 4.47% (2021) ➢ Inflation (CPI): 0.28% France Overview and Economic Summary France is a semi-presidential republic and a member of the European Union. Its national language is French and national currency is the Euro. France has a strong international presence, and has the 2nd largest economy in the European Union after Germany. The French economy has a capitalistic basis; French leaders commit to social equity through the use of laws, tax policies, and social spending to mitigate economic inequality. Historically, issues with the French economy have stemmed from high government spending and low growth.2 Many large companies and corporations are privately owned; however, the government maintains a strong presence in many sectors (power, public transport, defense industries). France ranked 4th in the Fortune Global 500 with 31 out of 500 of the world’s largest companies. The top five largest companies are Total S.A. (oil and gas), AXA (insurance), Carrefour (retail), Credit Agricole (banking), and Peugeot (automotive).3 COVID-19 Impact The French economy has taken a substantial hit from COVID-19, with a sharp decline in GDP and rise in unemployment (some sources show a lower unemployment rate due to a large portion of the population being unable to seek jobs and therefore not included in the unemployment rate). -

Economy of Foreign Countries

MOLDOVA INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC RELATIONS Economy of foreign countries TRAINING MANUAL Edited by Y. Kozak, А. Gribincea Chisinau-IRIM 2019 ISBN Economy of foreign countries : Training manual . - Edited by Y. Kozak, А. Gribincea – Chisinau- IRIM, , 2019 - 210 p. Recommended by the Academic Council of TSU Recommended by the Academic Council of ONEU Recommended by the Academic Council of IRIM Authors: Y. Kozak , А. Gribincea , Т.Shengelia , V. Kovalevsky, L. Sandyuk, O. Sulym , V.Kurylyak, , D.Burlachenko, The training manual contains the most important information about the economies of foreign countries. The peculiarities of the structure of national economies of individual states, typological and regional groups of countries, factors and trends of their development, internal and external economic policies of states and regional associations, features of their business cultures are considered. The development of the economies of the countries of the world is analyzed in the context of their foreign economic relations, the evolution of modern integration processes. Manual is intended for students of economic universities and faculties of the specialty "International economic relations", for specialists in the field of international economy. © Yuriy Kozak , 2019 © IRIM , 2019 CONTENTS PREFACE 5 CHAPTER I. THE NATIONAL ECONOMIES IN THE WORLD 7 ECONOMIC SYSTEM 1.1. The notion and main characteristics of the national economy 7 1.2. Main indicators of the country's economic development 16 1.3. The essence and direction of state economic policy. Models of economic development 24 1.4. Ethno-cultural features of national economies 28 1.5. Globalization of modern international relations and integration 30 processes in the world economy 1.5.1. -

Sundays, Socialism, and Neoliberal Modernity

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Summer 2016 What's Happened to France? Sundays, Socialism, and Neoliberal Modernity Michael Vincent Metz San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Metz, Michael Vincent, "What's Happened to France? Sundays, Socialism, and Neoliberal Modernity" (2016). Master's Theses. 4730. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.sm55-4hmm https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4730 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHAT’S HAPPENED TO FRANCE? SUNDAYS, SOCIALISM, AND NEOLIBERAL MODERNITY A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Michael V. Metz August 2016 ©2016 Michael V. Metz ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled WHAT’S HAPPENED TO FRANCE? SUNDAYS, SOCIALISM, AND NEOLIBERAL MODERNITY by Michael V. Metz APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY August 2016 Dr. Mary Pickering Department of History Dr. Allison Katsev Department of History Dr. Patrick Mardellat Economics, Politics, and History, Sciences Po, Lille, France ABSTRACT WHAT’S HAPPENED TO FRANCE? SUNDAYS, SOCIALISM, AND NEOLIBERAL MODERNITY by Michael V. Metz The "Macron Law," liberalizing French Sunday shopping hours, created great controversy in the French media in the winter of 2014-15, with particular opposition coming from the political left and the religious right. -

The French Revolution and 23 Napoleon, 1789–1815

CHAPTER The French Revolution and 23 Napoleon, 1789–1815 Essential Question Previewing Themes What was the impact of the French Revolution, the rise and fall of Napoleon, ECONOMICS The gap between rich and poor in France was vast. and the Congress of Vienna? The inequalities of the economy of France were a major cause of the French Revolution. What You Will Learn Geography Why do you think the royal palace at Versailles became a focal point for the anger of the poor people of Paris In this chapter you will learn about the French during the Revolution? Revolution, Napoleon Bonaparte's empire, and the Congress of Vienna. REVOLUTION Driven by the example of the American Revolution SECTION 1 The French Revolution Begins and such Enlightenment ideas as liberty, equality, and democracy, Economic and social inequalities the French ousted the government of Louis XVI and established a in the Old Regime helped cause the French new political order. Revolution. Geography Why do you think some historians cite the “wind from SECTION 2 Revolution Brings Reform and Terror America” as a cause of the French Revolution? The revolutionary government of France made reforms but also used terror and POWER AND AUTHORITY After seizing power in 1799, Napoleon violence to retain power. conquered a huge empire that included much of Western Europe. SECTION 3 Napoleon Forges an Empire His attempt to conquer Russia, however, led to his downfall. Napoleon Bonaparte, a military Geography What challenges and hazards of invading Russia might genius, seized power in France and made be inferred from the map? himself emperor. -

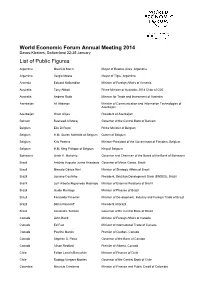

List of Public Figures

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2014 Davos-Klosters, Switzerland 22-25 January List of Public Figures Argentina Mauricio Macri Mayor of Buenos Aires, Argentina Argentina Sergio Massa Mayor of Tigre, Argentina Armenia Edward Nalbandian Minister of Foreign Affairs of Armenia Australia Tony Abbott Prime Minister of Australia; 2014 Chair of G20 Australia Andrew Robb Minister for Trade and Investment of Australia Azerbaijan Ali Abbasov Minister of Communication and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev President of Azerbaijan Bahrain Rasheed Al Maraj Governor of the Central Bank of Bahrain Belgium Elio Di Rupo Prime Minister of Belgium Belgium H.M. Queen Mathilde of Belgium Queen of Belgium Belgium Kris Peeters Minister-President of the Government of Flanders, Belgium Belgium H.M. King Philippe of Belgium King of Belgium Botswana Linah K. Mohohlo Governor and Chairman of the Board of the Bank of Botswana Brazil Antônio Augusto Junho Anastasia Governor of Minas Gerais, Brazil Brazil Marcelo Côrtes Neri Minister of Strategic Affairs of Brazil Brazil Luciano Coutinho President, Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), Brazil Brazil Luiz Alberto Figueiredo Machado Minister of External Relations of Brazil Brazil Guido Mantega Minister of Finance of Brazil Brazil Fernando Pimentel Minister of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade of Brazil Brazil Dilma Rousseff President of Brazil Brazil Alexandre Tombini Governor of the Central Bank of Brazil Canada John Baird Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada Canada Ed Fast Minister -

GENERAL AGREEMENT on 10 July 1968 TARIFFS and TRADE Limited Distribution

RESTRICTED GENERAL AGREEMENT ON 10 July 1968 TARIFFS AND TRADE Limited Distribution COUNCIL 4-5 July 1968 MINUTES OF MEETING Held at the Palais des Nations, Geneva, on 4 July 1968 Chairman: Mr. S. Chr. SOMMERFELT (Norway)l Subject discussed: French trade measures 1. French trade measures (L/3035 and Add.l) The French representative said that the economic and social life of France had recently been affected by social events that constituted an exceptional phenomenon in recent history. Since the General Agreement had entered into force it was the first time that a contracting party had found itself faced with the problems currently confronting France. The entire producing sector had been completely paralyzed for five weeks, either as a direct effect of strikes or indirectly as a result of the virtually complete standstill in the sectors of transport, production and distribution of power, post and telecommunications. The crisis had shaken the French economy to its foundations. In order to ensure a normal resumption of activity, the public authorities as well as individual enterprises were obliged to make major adjustments within a very short period. There were problems of all kinds: interruption of production and decline of stocks, budget difficulties, future investments which would be seriously affected by the increase in wages and other production costs. The immediate incidence of the wage increase was as much as 20 per cent in certain sectors, and wages in the lowest brackets had been raised by 35 per cent in a single step. The rise in production costs threatened to generate dangerous inflationary tension. -

The Evolution of France's European Monetary Diplomacy

THE EVOLUTION OF FRANCE'S EUROPEAN MONETARY DIPLOMACY THE EVOLUTION OF FRANCE'S EUROPEAN MONETARY DIPLOMACY by Alan J. Dillingham Assistant Professor Political Science Department Villanova University Villanova, PA 19085 (610) 519-4736 Email: [email protected] Prepared for the Fourth Biennial International Conference European Community Studies Association Charleston, South Carolina USA May 11-14, 1995 ** Not to be quoted without the author's permission ** ** Comments are welcome ** * The author would like to thank the Centre d'Etudes et de Recherches Internationales in Paris for hosting the author's preliminary research for this paper. The author also gratefully acknowledges the financial support received from the French Government through the Bourse Chateaubriand program. "The monetary construction of Europe resembles the myth of Sisyphus in its origins, but will finish, I hope, as well as the Aeneid." - Valéry Giscard d'Estaing January 25, 1974 This paper seeks to shed light on the factors driving European monetary integration by examining changes in France's diplomacy towards this issue since 1969. Because France has long been the principal advocate of European monetary integration (indeed, the Maastricht Treaty itself is the result of a French diplomatic initiative launched in January 1988), the French case is certainly significant. However, the French case also presents an interesting paradox: Why has the European country most notoriously jealous of its national sovereignty also been the leading proponent for European monetary integration? Since 1969, there has been a definite movement in French monetary diplomacy away from national sovereignty and towards greater integration. While Charles de Gaulle saw no need for coordinated policies, new European institutions or compromising French national sovereignty in any way, his successor, Georges Pompidou, proposed closer European cooperation through a narrowing of intra-EC parity margins and the creation of a Community Reserve Fund. -

Regional Defence Economic Outlook 2021 Europe and Russia Alma Dahl and Per Olsson

DEFENCE ECONOMICS AND MATERIEL SUPPLY Regional Defence Economic Outlook 2021 Europe and Russia Alma Dahl and Per Olsson This memo complements Defence Economic Outlook 2020 (DEO 2020), which assessed the global power balance focusing on the major world powers, with a regional outlook on Europe and Russia. The memo aims to provide a regional perspective not contained within DEO 2020. Similar to DEO 2020, the regional power balance in this memo is described in terms of military expenditure and macroeconomic trends during the period 2011-2020, fo- cusing on the five largest military spenders. Furthermore, the memo provides a description of the defence indu- strial capabilities of these countries, as well as the regional security environment. Figur 1: European military expenditure, 2020 (current prices). Source: SIPRI (2021) Europe, including Russia, is currently home to four of to roughly 16 percent of the European regional total. the world’s ten largest military spenders, accounting This makes Russia the largest military spender in the re- for USD 378.4 billion in military expenditure in 2020. gion, as seen in Table 1. In the same year, the UK was This is equal to 19.6 percent of global military spen- the second largest military spender with USD 59.2 bil- ding, a share which has declined from 21.8 percent in lion, followed by Germany with USD 52.8 billion and 2011. According to SIPRI, Russia’s military expendi- France with USD 52.7 billion. Italy was the region’s ture amounted to USD 61.7 billion in 2020, equivalent fifth largest spender with USD 28.9 billion in 2020.