The Structure of the Nervous System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Jimmy) Dooley

Updated: 10/12/2017 JAMES (JIMMY) DOOLEY Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences Lab: (319) 335-3975 University of Iowa Mobile: (714) 308-2784 E11 Seashore Hall E-mail: [email protected] Iowa City, Iowa 52242 EDUCATION B.A. 2009 Biology and Psychology, honors University of Chicago Honors advisor: Dr. Brian Prendergast Awarded June, 2009 Ph.D. 2015 Neuroscience University of California, Davis Advisor: Dr. Leah Krubitzer Awarded September, 2015 Dissertation: Anatomical connections of parietal cortex and visual acuity in Monodelphis domestica: Insights into the brain organization of the mammalian ancestor. CURRENT AND PREVIOUS POSITIONS Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Iowa, Dr. Mark Blumberg 2016 – present Postdoctoral Scholar, University of California, Davis, Dr. Leah Krubitzer 2015 Rotation Student, University of California, Davis, Dr. Barbara Chapman 2010 Rotation Student, University of California, Davis, Dr. Brian Trainor 2009 Research Assistant, University of Chicago, Dr. Brian Prendergast 2007 – 2009 COURSES ATTENDED Cold Spring Harbor Neural Data Science July 2017 Barcelona Cognition, Brain, and Technology Summer School September 2014 ACADEMIC AWARDS, HONORS, AND SPECIAL RECOGNITION College of Biological Sciences Student Spotlight July 2015 Ling-Lie Cha Graduate Student Award 2015 UC Davis Graduate Student Travel Award 2014 UC Davis Center for Visual Science Travel Fellowship 2014 Travel award to attend the International Society for Developmental 2014 Neurobiology meeting 1st place, Best Student Project, Barcelona -

Modular Subdivisions of Dolphin Insular Cortex: Does Evolutionary History Repeat Itself?

Modular Subdivisions of Dolphin Insular Cortex: Does Evolutionary History Repeat Itself? Paul Manger, Monika Sum, and Michael Szymanski University of California, Davis Downloaded from http://mitprc.silverchair.com/jocn/article-pdf/10/2/153/1758298/089892998562627.pdf by guest on 18 May 2021 Sam Ridgway Naval Command Control and Ocean Surveillance Center Leah Krubitzer University of California, Davis Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/jocn/article-pdf/10/2/153/1931754/089892998562627.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 Abstract ■ The structural organization of the insular cortex in the cortex, varies dramatically. Indeed, despite the tremendous ex- bottlenose dolphin was investigated by examining Nissl- and pansion of the cetacean neocortex, the size of the modules in myelin-stained tissue that was sectioned coronally and tangen- the insular cortex is similar to that described for small-brained tially. An uneven distribution of cell clusters that coincided mammals like the mouse, suggesting that module size is evolu- with myelin-light zones was observed in layer II. When the tionarily stable across species. Selection for optimal-size proc- present observations were compared to descriptions of mod- essing units, in terms of the lengths of connections within and ules in other animals, we found that the range of module size between them, is a likely source of this stability. ■ is restricted, while the size of the brain, particularly the neo- INTRODUCTION Mountcastle (1978) was not a ªxed structure in the cortex, and he proposed that the cortex should “not be The notion that the neocortex is divided into functional regarded as a collection of isolated units cemented to- parts was popularized almost a century ago by Brod- gether in a mosaic.” mann (1909). -

Article (Published Version)

Article Play, attention, and learning: How do play and timing shape the development of attention and influence classroom learning? HEDGES, James H., et al. Abstract The behavioral and neurobiological connections between play and the development of critical cognitive functions, such as attention, remain largely unknown. We do not yet know how these connections relate to the formation of specific abilities, such as spatial ability, and to learning in formal environments, such as in the classroom. Insights into these issues would be beneficial not only for understanding play, attention, and learning individually, but also for the development of more efficacious systems for learning and for the treatment of neurodevelopmental disorders. Different operational definitions of play can incorporate or exclude varying types of behavior, emphasize varying developmental time points, and motivate different research questions. Relevant questions to be explored in this area include, How do particular kinds of play relate to the development of particular kinds of abilities later in life? How does play vary across societies and species in the context of evolution? Does play facilitate a shift from reactive to predictive timing, and is its connection to timing unique or particularly significant? This [...] Reference HEDGES, James H., et al. Play, attention, and learning: How do play and timing shape the development of attention and influence classroom learning? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2013, vol. 1292, no. 1, p. 1-20 DOI : 10.1111/nyas.12154 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:91882 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Ann. -

The Evolution of Parietal Areas Involved in Hand Use in Primates. In

Krubitzer L and Disbrow E. (2008) The evolution of parietal areas involved in hand use in primates. In: The Senses: A Comprehensive Reference; Kaas JH and Gardner E (Eds.), Volume 6, Somatosensation, Chapter 10 (pp. 183-214). Elsevier, London. 6.10 The Evolution of Parietal Areas Involved in Hand Use in Primates L Krubitzer, Department of Psychology, Center for Neuroscience, University of California, Davis, CA, USA E Disbrow, Department of Neurology, Center for Neuroscience, University of California, Davis; Department of Radiology, San Francisco, CA, USA Submitted, 2005; Published by Elsevier Inc. 6.10.1 Introduction 184 6.10.2 Sensory Versus Association Cortex 184 6.10.3 Organization of Anterior Parietal Cortex in Primates (Areas 3b, 3a, 1, and 2) 186 6.10.4 Area 3b or S1 187 6.10.4.1 Functional Organization 187 6.10.4.2 Connections 191 6.10.5 Area 3a 195 6.10.5.1 Functional Organization 195 6.10.5.2 Connections 198 6.10.6 Area 1 198 6.10.6.1 Functional Organization 198 6.10.6.2 Connections 200 6.10.7 Area 2 200 6.10.7.1 Functional Organization 200 6.10.7.2 Connections 203 6.10.8 Posterior Parietal Area 5 in Primates 203 6.10.8.1 Functional Organization 203 6.10.8.2 Connections 204 6.10.9 Is Area 5 Homologous Across Mammals? 206 6.10.10 The Evolution of Anterior and Posterior Parietal Cortex 206 References 208 Glossary acallosal A neural pathway that does not project to extrastriate Visual cortex that does not include V1 the contralateral hemisphere and does not receive (striate cortex). -

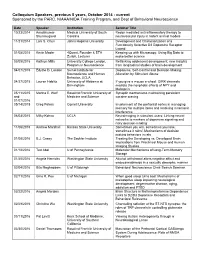

Colloquium Speakers, Previous 5 Years, October 2014 - Current Sponsored by the PARC, NIAAA/NIDA Training Program, and Dept of Behavioral Neuroscience

Colloquium Speakers, previous 5 years, October 2014 - current Sponsored by the PARC, NIAAA/NIDA Training Program, and Dept of Behavioral Neuroscience Date Speaker Institution Seminar Title 10/23/2014 Anadakumar Medical University of South Redox mediated anti-inflammatory therapy to Shunmugavel Carolina neurovascular injury in rodent animal models 11/21/2014 Lani S. Chun Johns Hopkins University Development and Characterization of a Functionally Selective D2 Dopamine Receptor Ligand 01/05/2015 Kevin Mader 4Quant, Founder & ETH Keeping up with Microscopy: Using Big Data to Zurich, Lecturer make better science 03/09/2015 Kathryn Mills University College London, Rethinking adolescent development: new insights Program in Neuroscience from longitudinal studies of brain development 04/07/2015 Edythe D. London Semel Institute for Dopamine, Self-Control and Decision-Making: Neuroscience and Human Alteration by Stimulant Abuse Behavior, UCLA 04/27/2015 Lauren Hablitz University of Alabama at If you give a mouse a wheel: GIRK channels Birmingham mediate the nonphotic effects of NPY and Melatonin 05/11/2015 Marina E. Wolf Rosalind Franklin University of Synaptic mechanisms maintaining persistent and Medicine and Science cocaine craving 01/07/2016 05/14/2015 Greg Peters Cornell University Involvement of the prefrontal cortex in managing memory for multiple items and resolving mnemonic interference 06/04/2015 Milky Kohno UCLA Neuroimaging in stimulant users: Linking neural networks to markers of dopamine signaling and risky decision-making 11/06/2015 Andrew Marshall Kansas State University Sometimes you win, sometimes you lose, sometimes it rains': Mechanisms of decision making behaviors in rats 01/08/2016 B.J. Casey The Sackler Institute Treating the Developing vs. -

Leah Krubitzer, Phd.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER SCHOOL OF MEDICINE AND DENTISTRY DEPARTMENT OF NEUROSCIENCE AND THE ERNEST J. DEL MONTE INSTITUTE FOR NEUROSCIENCE present Mary Notter Lecture Leah Krubitzer, Ph. D. Professor Department of Psychology University of California Davis, CA Cortical Plasticity within and across lifetimes The neocortex is the part of the brain that is involved in perception, cognition, and volitional motor control. In mammals it is a highly dynamic structure that has been dramatically altered within an individual’s lifetime and in different lineages throughout the course of evolution. These alterations account for the remarkable variations in behavior that species exhibit. Because we cannot study the evolution of the neocortex directly, we must make inferences about the evolutionary process from a comparative analysis of brains, and study the developmental mechanisms that give rise to alterations in the brain. Comparative studies allow us to appreciate the types of changes that have been made to the neocortex and the similarities that exist across taxa, and ultimately the constraints imposed on the evolving brain. Developmental studies inform us about how phenotypic transitions may arise by alterations in developmental cascades or changes in the physical environment in which the brain develops. We focus on how early experience shapes the functional organization and connectivity of each individual’s brain and behavior to be uniquely optimized for a given sensory milieu. Such plasticity plays an integral role in shaping the brains of normal individuals, as well as those that have lost or altered sensory inputs, such as congenitally deaf or blind individuals. This loss of sensory input early in development leads to dramatic changes in both the normal organization and connections of the neocortex as well as in sensory mediated behavior. -

Leah A. Krubitzer, Ph.D

Curriculum Vitae Leah A. Krubitzer, Ph.D. E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 530-757-8868 Center for Neuroscience Department of Psychology University of California, Davis University of California, Davis 1544 Newton Court One Shields Avenue Davis, CA 95618 134 Young Hall Davis, CA 95616 Personal Date of Birth: March 30, 1961 Place of Birth: Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania USA Education 1983 B.S. Speech Pathology, High Honors Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 1984 – 1989 Ph.D. Psychology (Neuroscience), Thesis Adviser: Dr. Jon H. Kaas Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN Professional Appointments and Experience 1989 – 1990 Postdoctoral Fellow with Dr. Jon H Kaas Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA 1990 - 1992 ARC Research Associate. Postdoctoral advisor: Dr. Mike Calford. Vision, Touch and Hearing Research Centre, Department of Physiology and Pharmacology University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia 1993 – 1995 ARC Research Fellow Vision, Touch and Hearing Research Centre, Department of Physiology and Pharmacology University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia 1995 – 1998 Assistant Professor Department of Psychology, and Center for Neuroscience UC Davis, Davis, CA, USA 1999 – 2001 Associate Professor III Department of Psychology, and Center for Neuroscience 1 UC Davis, Davis, CA, USA 2001 – 2003 Professor I Department of Psychology, and Center for Neuroscience UC Davis, Davis, CA, USA 2003 – 2006 Professor II Department of Psychology, and Center for Neuroscience UC Davis, Davis, CA, USA 2006 – 2008 Professor III Department -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Leah A. Krubitzer, Ph.D. E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 530-757-8868 Center for Neuroscience Department of Psychology University of California, Davis University of California, Davis 1544 Newton Court One Shields Avenue Davis, CA 95618 134 Young Hall Davis, CA 95616 Personal Date of Birth: March 30, 1961 Place of Birth: Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania USA Education 1983 B.S. Speech Pathology, High Honors Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 1984 – 1989 Ph.D. Psychology (Neuroscience), Thesis Adviser: Dr. Jon H. Kaas Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN Professional Appointments and Experience 1989 – 1990 Postdoctoral Fellow with Dr. Jon H Kaas Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA 1990 - 1992 ARC Research Associate. Postdoctoral advisor: Dr. Mike Calford. Vision, Touch and Hearing Research Centre, Department of Physiology and Pharmacology University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia 1993 – 1995 ARC Research Fellow Vision, Touch, and Hearing Research Centre, Department of Physiology and Pharmacology University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia 1995 – 1998 Assistant Professor Department of Psychology, and Center for Neuroscience UC Davis, Davis, CA, USA 1999 – 2001 Associate Professor Department of Psychology, and Center for Neuroscience UC Davis, Davis, CA, USA 2001 – 2020 Professor Department of Psychology, and Center for Neuroscience UC Davis, Davis, CA, USA 2020 – present Distinguished professor Department of Psychology, and Center for Neuroscience UC Davis, Davis, CA USA 1 Honors and Awards 1987 -

The Journal of Neuroscience September 19, 2007 • Volume 27 Number 38

The Journal of Neuroscience September 19, 2007 • Volume 27 Number 38 www.jneurosci.org i This Week in The Journal Toolbox 10073 The Serial Reaction Time Task: Implicit Motor Skill Learning? Edwin M. Robertson Journal Club 10076 Temporal Encoding of Movement in Motor Cortical Neurons J. Andrew Pruszynski, Angela M. Coderre, Timothy P. Lillicrap, and Isaac Kurtzer Cover legend: Lateral three-dimensional view of Articles white matter tracts from the dorsal and ventral CELLULAR/MOLECULAR subregions of the human lateral premotor cortex. Blue tracts represent white matter connections from dorsal 10084 Signaling Properties of a Short-Wave Cone Visual Pigment and Its Role premotor cortex; red tracts show white matter in Phototransduction pathways from ventral premotor cortex. Diffusion Guang Shi, King-Wai Yau, Jeannie Chen, and Vladimir J. Kefalov imaging tractography was used to subdivide human 10165 NMDA Receptor Surface Trafficking and Synaptic Subunit Composition Are premotor cortex in vivo based on its pattern of Developmentally Regulated by the Extracellular Matrix Protein Reelin anatomical connections. The dorsal and ventral parts Laurent Groc, Daniel Choquet, F. Anne Stephenson, Danie`le Verrier, of human premotor cortex are shown to form part of Olivier J. Manzoni, and Pascale Chavis distinct parieto-frontal circuits, similar to those previously reported in macaque monkey. The 10176 Tomosyn Negatively Regulates CAPS-Dependent Peptide Release at Caenorhabditis anatomical subdivision of premotor cortex is found to elegans Synapses fit well with divisions based on functional imaging Elena O. Gracheva, Anna O. Burdina, Denis Touroutine, data. For more information, see the article by Martine Berthelot-Grosjean, Hetal Parekh, and Janet E. -

Neuroscience Initiative ______

HEMINGWAY COLLABORATIVE PROJECT: WSU NEUROSCIENCE INITIATIVE ___________________________ ___________________________ 2007-2008 ANNUAL REPORT HEMINGWAY COLLABORATIVE PROJECT: WSU NEUROSCIENCE INITIATIVE 2007-2008 ANNUAL REPORT Funded by a Hemingway Collaborative Grant (and funds from three separate colleges and three departments), the Neuroscience Initiative is an interdepartmental effort to: a) assess and report on WSU student and faculty interest in neuroscience; b) design a set of neuroscience courses that could be “stand-alone” offerings, or serve as a core for a minor or major; c) engage and educate WSU students and faculty on neuroscience topics by inviting internationally-renowned scientists from nearby universities to speak on campus, and; d) build neuroscience research collaborations for faculty and students that would be competitive for extramural funding. Project Director: Dr. Matthew Schmolesky (Psychology). Core participants: Drs. Lauren Fowler (Psychology), Jim Hutchins (Health Sciences), and Barbara Trask (Zoology). Additional participants: Drs. Eric Amsel (Psychology), Aaron Ashley (Psychology), Norris Bancroft (Psychology), Nicole Berthelemy-Okazaki (Zoology), Jonathan Clark (Zoology), Stephen Clark (Botany), Marie Kotter (Health Sciences), Ron Meyers (Zoology), and Sam Zeveloff (Zoology). College and Departmental Support: $1000 each from Deans Conroy (Health Professions), Ostlie (Science), and Sadler (Social and Behavioral Sciences); $200 each from Chairs Amsel (Psychology), Kotter (Health Sciences), and Zeveloff (Zoology). Since September, 2007, Neuroscience Initiative (NI) members have made exceptional progress in a wide range of activities that support the initial NI goals. Gauging interest in neuroscience at WSU • A survey was developed to gauge student interest in neuroscience coursework, a Neuroscience Minor, or a Neuroscience Major. To date, the survey had been administered to 598 students in over 20 different courses offered by the College of Health Professions, College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, and College of Science. -

MLPHAN CV September2018

Mimi Le Phan, Ph.D. Psychology-Busch Campus Rutgers University 152 Frelinghuysen Rd. Piscataway, NJ 08854 Phone: (848) 445-8954 E-mail: [email protected] Education • Ph.D. in Neuroscience, University of California, Davis (Davis, CA), December 2001 Dissertation: Factors Underlying the Perception of Sound Locations and Temporal Discrimination of Rapidly Presented Acoustic Stimuli in the Primate Auditory Cortex Committee: Gregg Recanzone, Ph.D. (advisor), Mitch Sutter, Ph.D., Leah Krubitzer, Ph.D. • B.A. in Biology, Rutgers College (New Brunswick, NJ), June 1992 • B.A. High Honors in Psychology, Rutgers College (New Brunswick, NJ), June 1992 Primary Appointments • Psychology Department, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey (New Brunswick, NJ) Associate Research Professor 2018- Assistant Research Professor 2010-2018 Research Associate 2006-2010 Postdoctoral Associate 2002-2006 Fields Systems and behavioral neuroscience with an emphasis on auditory plasticity/stability and perceptual functions in humans, non-human primates, rodents, and songbirds across the lifespan and pathologies. Epigenetic regulation of and developmental influences on sensory and sensorimotor learning and memory. Modelling of infant vocal learning. Funding • Grant Number: R15 HD085102 Principal Investigator: Pytte, Carolyn L. / Phan, Mimi L. / Remage-Healey, Luke Project Title: Effects of Statins on Juvenile Learning, Memory and Neuroestrogen Project Period: 08/06/2015 - 07/31/2019 • Grant Number: R03 HD068960 Principal Investigator: Phan, Mimi L. / Pytte, Carolyn L. Project Title: Effects of Statins on the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory Across the Lifespan Project Period: 3/4/2011 - 2/28/2014 • Grant Number: The Busch Biomedical Grant Program (Rutgers University) Principal Investigator: Phan, Mimi L. Project Title: Effects of Statins on Neural Processes of Learning and Memory Across the Lifespan Project Period: 7/1/2010 - 5/1/2012 • Grant Number: R03 DC007971 Principal Investigator: Phan, Mimi L. -

Early Sensory Experiences Shape Brain Structure and Function Animal Research Shows That Too Much Or Too Little Sensory Stimulation Can Affect How the Brain Develops

Embargoed until Nov. 13, noon PST Contacts: Emily Ortman, (202) 962-4090 Press Room, Nov. 12-16: (619) 525-6230 Kym Kilbourne, (202) 962-4060 Early Sensory Experiences Shape Brain Structure and Function Animal research shows that too much or too little sensory stimulation can affect how the brain develops SAN DIEGO — Environmental enrichment, sensory stimulation, and sensory deprivation all shape the connections and organization in the brain, in addition to affecting behavior, as shown by new research presented at Neuroscience 2016, the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience and the world’s largest source of emerging news about brain science and health. The brains of animals, including humans, adapt throughout the course of their lifetimes. Every experience changes the brain in some way, but sensory experiences in particular profoundly influence brain development. And those that occur very early in development carry the most impact on brain structure and function. Today’s new findings show that: Rats raised in a natural, outdoor environment show differences in brain organization and behavior from rats raised in standard laboratory cages (Leah Krubitzer, abstract 807.12, see attached summary). Mice exposed to excessive sensory stimulation early in life are more impulsive and susceptible to cocaine (Jan-Marino Ramirez, abstract 392.10, see attached summary). Other recent findings discussed show that: The auditory brain structure of a person deaf from birth appears the same as that of a hearing person (Ella Striem- Amit, abstract 48.09, see attached summary). “Today’s findings show the progress we’re making in understanding how early sensory experiences affect brain development and future behavior,” said press conference moderator Gina Turrigiano, PhD, of Brandeis University.