BEAM Mitchell Environment Group Inc.1.55 MB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outreach Survey on Natural and Working Lands

Responses to Outreach Survey This document lists all responses to the question below, from the outreach survey open from January 25, 2021 through May 3, 2021. The survey was made available on the Oregon Global Warming Commission’s webpage on Natural and Working Lands. For more information on the Commission’s work, see https://www.keeporegoncool.org/ Natural and Working Lands Outreach Survey Q1 What should we propose as a goal for reduced emissions and increased sequestration in natural and working lands? Answered: 114 Skipped: 8 # RESPONSES DATE 1 50% reduction in emissions in the first 10 years, followed by additional 50% decreases in 5/3/2021 4:16 PM subsequent 10 year periods. 25% increased sequestration in first 10 years, followed by additional 25% increases in subsequent 10 year periods. 2 We recommend both an emissions reduction goal and an activity-based goal. An emissions 5/3/2021 3:54 PM reduction goal is important for determining whether we are making progress toward the state’s emissions reduction goals. The Commission should consider whether to recommend both an emissions reduction and carbon sequestration goal separately, or at least clarify how sequestration is calculated into an emissions reduction goal if it is part of that goal. And an activity-based goal will provide an opportunity for natural and working lands stakeholders, including farmers, ranchers, and foresters to engage. It can help to determine whether new programs, policies and practices have been effective and are resulting in measurable changes. An example of an activity-based goal is: Increase adoption of practices that have the potential to reduce emissions and/or sequester carbon in the soil. -

Cedar River Watershed Tour and Wood Sourcing Workshop – Wednesday, September 11

Cedar River Watershed Tour and Wood Sourcing Workshop – Wednesday, September 11 Why attend: The members of the US Green Building Council recently voted to approve a new version of LEED, the largest green building program in the world, which maintains a credit for use of Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certified wood. And the Living Building Challenge, the most rigorous benchmark of sustainability in the built environment, requires all new wood to be FSC certified. Builders, architects, developers, and chain-of-custody managers should attend this tour to learn about green building opportunities with FSC products and what this sourcing means for forests and Puget Sound watersheds. Overview: Join this tour for a rare opportunity to visit the City of Seattle’s Cedar River Watershed, a 100,000 acre FSC certified forest that serves as the drinking water source for 1.4 million residents. Participants will explore the woods with trained experts to get a firsthand experience of responsible forest management, habitat restoration, and connectivity from forest to market. Forest cover and sustainable management are key forces in protecting watershed dynamics and the biological and economic health of Puget Sound. Following the interactive tour, a lunchtime presentation and Q&A about the timber supply chain will provide a distinct perspective on production, distribution, and sourcing opportunities. Participants will then engage in a hands-on workshop to improve the flow of FSC certified timber and grow the FSC market in the Northwest. This tour has -

SOUTH EAST FOREST RESCUE PO BOX 899 Moruya, NSW, 2537 [email protected]

SOUTH EAST FOREST RESCUE PO BOX 899 Moruya, NSW, 2537 [email protected] Committee Secretary Senate Standing Committees on Environment and Communications PO Box 6100 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 By Email: [email protected] Dear Committee, Re: Senate Committee Inquiry into The Effectiveness of Threatened Species and Ecological Communities’ Protection in Australia The situation in NSW is critical in a native forestry context. There is clear evidence of systematic significant damage to native forests in southern NSW as a result of government- supervised logging. The logging of mapped old-growth, rocky outcrops, gazetted Aboriginal Place, National Park, FMZs, of Special Protection Zones, inaccurate surveys and damage to threatened and endangered species habitat has occurred in direct breach with legislative instruments and has significantly impacted on matters of national environmental significance, marine water quality and EPBC listed species. These state regulations have been in place for 14 years, they are simple to follow and yet they are being broken regularly. Citizens cannot take FNSW to court. The NSW EPA is reluctant, even though there is significant environmental damage. The EPA are not capable of robustly regulating and have audited a mere 3% of logging operations over a 5 year period. As FNSW is state run, state owned and state regulated there is no possibility of halting this destruction. If the Commonwealth hands over regulation to the States there will be nothing to stand in the way of States who are conflicted. The EPBC Act is far from perfect but it represents hard won gains and is at least some measure of protection in non-IFOA areas. -

A GUIDE to MANAGING Box Gum Grassy Woodlands

A GUIDE TO MANAGING Box Gum Grassy Woodlands KIMBERLIE RAWLINGS | DAVID FREUDENBERGER | DAVID CARR II A Guide to Managing Box Gum Grassy Woodlands A GUIDE TO MANAGING Box Gum Grassy Woodlands KIMBERLIE RAWLINGS | DAVID FREUDENBERGER | DAVID CARR III © Commonwealth of Australia 2010 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 or posted at www.ag.gov.au/cca This publication was funded by Caring for our Country – Environmental Stewardship Rawlings, Kimberlie A guide to managing box gum grassy woodlands/Kimberlie Rawlings, David Freudenberger and David Carr. Canberra, A.C.T.: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, 2010. ISBN: 978-0-9807427-8-7 1. Forest regeneration – Australia 2. Forest management – Australia 3. Remnant vegetation management – Australia I. Freudenberger, David II. Carr, David III. Greening Australia 333.750994 Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for Environment Protection, Heritage and the Arts, the Minister for Climate Change, Energy Efficiency and Water or the Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. -

Mitchell Shire Council

ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING UNDER SEPARATE COVER ATTACHMENTS 21 MARCH 2016 MITCHELL SHIRE COUNCIL Council Meeting Attachment ENGINEERING AND INFRASTRUCTURE 21 MARCH 2016 9.1 DRAFT RURAL ROADSIDE ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN 2016-2026 Attachment No: 1 Draft Rural Roadside Environmental Management Plan 2016-2026 MITCHELL SHIRE COUNCIL Page 1 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Aim .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Objectives ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Council’s Responsibility for Roadsides .................................................................................................... 5 Scope ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 What is a Roadside? ............................................................................................................................ 6 The Maintenance Envelope ................................................................................................................ 6 VicRoads Controlled Roads ................................................................................................................ -

Ecological Burning in Box-Ironbark Forests: Phase 1 - Literature Review

DEPARTMENT OF SUSTAINABILITY AND ENVIRONMENT Ecological Burning in Box-Ironbark Forests: Phase 1 - Literature Review Report to North Central Catchment Management Authority Arn Tolsma, David Cheal and Geoff Brown Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Ecological Burning in Box-Ironbark Forests Phase 1 – Literature Review Report to North Central Catchment Management Authority August 2007 © State of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment 2007 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. General disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you, but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Report prepared by Arn Tolsma, David Cheal and Geoff Brown Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Sustainability and Environment 123 Brown St (PO Box 137) Heidelberg, Victoria, 3084 Phone 9450 8600 Email: [email protected] Acknowledgements: Obe Carter (now at Department of Primary Industries and Water, Tasmania) and Claire Moxham (Arthur Rylah Institute) made valuable contributions to the introductory section. Alan Yen (Department of Primary Industry) contributed substantially to the invertebrate section. Andrew Bennett (Deakin University) and Greg Horrocks (Monash University) provided expert advice on fauna effects. Nick Clemann (Arthur Rylah Institute) and Evelyn Nicholson (Department of Sustainability and Environment) provided feedback on reptiles and frogs. Matt Gibson (University of Ballarat) provided on-ground litter data. -

I Am Chief Scientist and President at Geos Institute, a Climate-Based Non- Lara J

SCIENCE ADVISORY January 14, 2020 BOARD Scott Hoffman Black Chair: Senator Jeff Golden Xerces Society Senate Interim Committee on Wildfire Prevention and Recovery January 14, 2020 hearing and public testimony Robert E. Gresswell, Ph.D. US Geological Survey Dear Chairman Golden and members of the Interim Committee: Healy Hamilton, Ph.D. NatureServe I am Chief Scientist and President at Geos Institute, a climate-based non- Lara J. Hansen, Ph.D. profit organization, in Ashland Oregon (www.geosinstitute.org). I am EcoAdapt submitting this testimony for the public record as substantive backup to Thomas Hardy, Ph.D. my 5-minute slide show (with graphics and charts) presented at the open Texas State University public session during the hearing. Mark Harmon, Ph.D. Oregon State University I am an Oregon resident of 22 years, a post-doctoral fellow and Adjunct Richard Hutto, Ph.D. Professor (previously) of Oregon State and Southern Oregon University of Montana universities, and a global biodiversity scientist. I have published over Steve Jessup, Ph.D. 200 scientific papers in peer-reviewed journals and several books Southern Oregon University covering forest ecology and management, conservation biology and climate change, wildfire ecology and management, and endangered Wayne Minshall, Ph.D. Idaho State University species conservation. My two recent books most germane to this hearing – “Disturbance Ecology and Biological Diversity” (CRC Press 2019, Reed Noss, Ph.D. University of Central Florida coeditor) and “The Ecological Importance of Mixed-Severity Fires: Nature’s Phoenix (Elsevier 2015, coeditor) – represent much of the latest Dennis Odion, Ph.D. University of California, science on wildfire that you may not have heard from other witnesses or Santa Barbara presenters on this issue. -

List of Parishes in the State of Victoria

List of Parishes in the State of Victoria Showing the County, the Land District, and the Municipality in which each is situated. (extracted from Township and Parish Guide, Department of Crown Lands and Survey, 1955) Parish County Land District Municipality (Shire Unless Otherwise Stated) Acheron Anglesey Alexandra Alexandra Addington Talbot Ballaarat Ballaarat Adjie Benambra Beechworth Upper Murray Adzar Villiers Hamilton Mount Rouse Aire Polwarth Geelong Otway Albacutya Karkarooc; Mallee Dimboola Weeah Alberton East Buln Buln Melbourne Alberton Alberton West Buln Buln Melbourne Alberton Alexandra Anglesey Alexandra Alexandra Allambee East Buln Buln Melbourne Korumburra, Narracan, Woorayl Amherst Talbot St. Arnaud Talbot, Tullaroop Amphitheatre Gladstone; Ararat Lexton Kara Kara; Ripon Anakie Grant Geelong Corio Angahook Polwarth Geelong Corio Angora Dargo Omeo Omeo Annuello Karkarooc Mallee Swan Hill Annya Normanby Hamilton Portland Arapiles Lowan Horsham (P.M.) Arapiles Ararat Borung; Ararat Ararat (City); Ararat, Stawell Ripon Arcadia Moira Benalla Euroa, Goulburn, Shepparton Archdale Gladstone St. Arnaud Bet Bet Ardno Follett Hamilton Glenelg Ardonachie Normanby Hamilton Minhamite Areegra Borug Horsham (P.M.) Warracknabeal Argyle Grenville Ballaarat Grenville, Ripon Ascot Ripon; Ballaarat Ballaarat Talbot Ashens Borung Horsham Dunmunkle Audley Normanby Hamilton Dundas, Portland Avenel Anglesey; Seymour Goulburn, Seymour Delatite; Moira Avoca Gladstone; St. Arnaud Avoca Kara Kara Awonga Lowan Horsham Kowree Axedale Bendigo; Bendigo -

Managing Red Gum Floodplain Ecosystems

Chapter 11 Managing red gum floodplain ecosystems 11.1 Overview 252 11.2 Goal for red gum floodplain ecosystem management 252 11.3 Management principles for resilient river red gum forests 252 11.4 Silvicultural systems, management practices and principles 263 11.5 Performance review 271 252 Riverina Bioregion Regional Forest Assessment: River red gum and woodland forests 11.1 Overview • AGS remains an appropriate silvicultural system for river red gum forests managed for production, as well as for The river red gum floodplain ecosystems of the Riverina other values as long as management prescriptions are bioregion are under high stress, and in some cases are improved. These include prescriptions for adequate watering transitioning to alternative states. They will require various regimes, the provision and maintenance of ecological levels of direct intervention to maintain their resilience, and values (principally the retention of habitat trees and coarse to continue to provide ecosystem services that the woody debris), and the intensity of its implementation. community values. 11.2 Goal for red gum floodplain ecosystem management We need to rethink our current approach to forest management. The NRC considers that management approaches for the river The NSW Government has adopted a long-term, red gum forests of the Riverina bioregion should be based aspirational goal to achieve: on recognition of ongoing water scarcity, clear management objectives, and build upon past forest conditions and resilient, ecologically sustainable landscapes functioning management activities (rather than attempting to replicate effectively at all scales and supporting the environmental, them). In particular, we need to learn as we go by trialling and economic, social and cultural values of communities testing different approaches for these ecosystems. -

9 12 Victorian Civil and Administrati…

ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA 17 AUGUST 2020 9.12 VICTORIAN CIVIL AND ADMINISTRATIVE TRIBUNAL HEARINGS AND ACTIVITIES CARRIED OUT UNDER DELEGATION Author: James McNulty - Manager Development Approvals File No: CL/04/004 Attachments: Nil SUMMARY The following is a summary of planning activity before the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) as well as a list of decisions on planning permit applications dealt with under delegated powers for the period detailed. RECOMMENDATION THAT Council receive and note the report on the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal Hearings and Activities carried out under delegation. Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) activity update. Upcoming appeals The following is an update of the upcoming VCAT appeals. APPEAL REFERENCE ADDRESS PROPOSAL APPEAL AGAINST DATE NOS. 5 October VCAT – 8 Eden Place, Development of Appeal against 2020 P125/2019 Wallan the land for Council’s refusal to Council – multiple grant a planning permit PLP206/18 dwellings September VCAT – Hillview Drive, Subdivision of Appeal against 2020 P1542/2019 Broadford the land into 25 Council’s refusal to Council – lots and the extend the completion TP93/100 removal of date of the permit native vegetation 23 March VCAT – Hogan’s Hotel, Construction of Conditions Appeal by 2021 P2492/2019 88-94 High an extension, applicant Council – Street, Wallan reduction in car PLP012/19 parking, increase in licensed area and patron numbers Awaiting VCAT – 8 C Emily Major Promotion Appeal against decision P9/2020 Street, Seymour -

Murrindindi Map (PDF, 3.1

o! E o! E E E E E E E E E E # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # Mt Camel # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # Swanpool # # Rushworth TATONG E Forest RA Euroa # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # +$ TATONG - TATO-3 - MT TATONG - REDCASTLE - # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # MITCHELL RD (CFA) TATONG WATCHBOX CHERRY TREE TK # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # CREEK +$ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # LONGWOOD - # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # REDCASTLE WITHERS ST # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # - PAVEYS RD Lake Nagambie # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # CORNER (CFA) # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # LONGWOOD Joint Fuel # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # Nagambie +$ - WITHERS # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # E STREET (CFA) # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # E LONGWOOD - MAXFIELD ST +$ SAMARIA PRIVATE PROPERTY (CFA) # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # - MT JOY +$ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # +$ +$+$ LONGWOOD - REILLY LA - +$+$ +$ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # +$ +$ PRIVATE PROPERTY (CFA) # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # REDCASTLE - +$+$ OLD COACH RD LONGWOOD +$ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # Management LONGWOOD # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # Graytown d - PUDDY R - PRIMARY # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # n LANE (CFA) i # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # a SCHOOL (CFA) M # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # e i # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # -

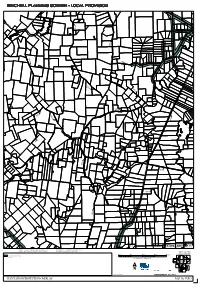

Mitchell Planning Scheme

Creek BASSET'S MITCHELLMITCHELL PLANNINGPLANNING SCHEMESCHEME- -TOOBORAC- LOCALLOCAL PROVISIONPROVISIONVPO1 MITCHELLMITCHELL PLANNINGPLANNING SCHEMESCHEMESEYMOUR -- LOCALLOCAL PROVISIONPROVISION RD POPPIES RD VPO1 Gardiner BASSET'S RD SEYMOUR - TOOBORAC RD VPO1 Ck Ck SEYMOUR RD TOOBORAC SEYMOUR - VPO1 VPO1 VPO1 RD RD Gardners Back PUCKAPUNYL Sugarloaf - RD PANYULE Creek - VPO1 VPO1 PYALONG RD GLENAROUA RD SEYMOUR RD - SPEED ASHES BRIDGE VPO1 PYALONG GLENAROUA VPO1 DAISYBURN RD RD RD VPO1 RD - VPO1 PUCKAPUNYL McGINTY'S Sugarloaf RD DUELL'S VPO1 SEYMOUR RD VPO1 - RD DUELL'S DAISYBURN PYALONG Sunday BRIDGE FREDDY'S RD TALLAROOK ASHES RD VPO1 BROADFORD - Creek RD SHIELDS PYALONG VPO1 VPO1 - PYALONG VPO1 SEYMOUR SUGARLOAF GREEN - RD VPO1 SHARPS CREEK RD TAYLORS RD PYALONG VPO1 JOHN'S RD RD RD VPO1 RD RD CHAPMAN'S VPO1 PYALONG RD RD SUNDAY CREEK - GLENAROUA SEYMOUR PYALONG Mollisons CREEK MUNCKTONS SCOTTS SEYMOUR Creek - FIGGINS Sunday - RD DOCKEREYS VPO1 CREEK CREEK BROADFORD VPO1 RD CAMERONS SUGARLOAF RD LA RD - RD - PYALONG VPO1 RD - BROADFORD Sunday BROADFORD RD PYALONG RD MOONEYS RD Creek LA BROADFORD RD VPO1 CREEK HOGANS BROWNS BROADFORD SUNDAY CREEK RD PYALONG McKENZIES - LA RD CAMERON'S - BROADFORD DWYERS SUGARLOAF VPO1 LA VPO1 CHAIN HOGANS SEYMOUR THREE - ROAD CREEK HUME LA RD Sugarloaf Creek KENNYS MARCH VPO1 KIMBERLY HIGH CAMP RD SCOTTS NORTHERN RD DR BANKS RD GLENAROUA GLENAROUA RD RD VPO1 - HWY LA KILMORE VPO1 THREE CHAIN FOR THIS AREA SEE MAP 11 Creek This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except This map should be read in conjunction with additional Planning Overlay RD RD TAATOOKE Creek in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act.