A Monument to a Regulatory System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President Meets President UR Field Patrol Unit Seligman Attends State of the Union Address Hockey Star Follows Tapped for Kidnapping Team USA

CampusTHURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 2016 / VOLUME 143, ISSUE 1 Times SERVING THE UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER COMMUNITY SINCE 1873 / campustimes.org New President Meets President UR Field Patrol Unit Seligman Attends State of the Union Address Hockey Star Follows Tapped for Kidnapping Team USA BY ANGELA LAI BY AUDREY GOLDFARB PUBLISHER CONTRIBUTING WRITER BY JUSTIN TROMBLY Confident and congenial, Tara MANAGING EDITOR Lamberti stands proud at 5’4”, the shortest goalie and only Divi- A new Department of Pub- sion III player in the country to lic Safety (DPS) patrol unit be invited to the U.S. National is set to roll out next month, Field Hockey Trials this month. coming in the wake of the The First Team All-American has kidnapping of two Univer- compiled a myriad of accolades sity seniors in early December. during her collegiate career. The The new unit, which will focus senior led the league in shutouts on giving DPS a visible and ac- this season and earned recog- cessible presence on campus, will nition as the Liberty League start patroling on Sunday, Feb. 7, Defensive Player of the Year, almost a month to the day after the but this invitation to take her students were abducted and held at talents to the next level is her gunpoint in an off-campus house. claim to fame. UR President Joel Seligman Passing up opportunities to announced the unit in a recent play at the Division I level, email to students, which dis- Lamberti chose UR to better cussed both the kidnapping and PHOTO COURTESY OF THE OFFICE OF CONGRESSWOMAN LOUISE SLAUGHTER balance academics, athletics, a Monroe County Grand Jury UR President Joel Seligman, Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi, and Representative Louise Slaughter mingle in Pelosi’s Capitol and social life, in addition to indictment against six defen- Hill office before President Barack Obama’s State of the Union address Jan. -

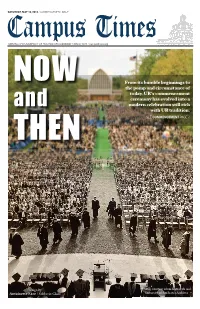

From Its Humble Beginnings to the Pomp and Circumstance of Today, UR's Commencement Ceremony Has Evolved Into a Modern Celebrati

CampusSATURDAY, MAY 18, 2013 / COMMENCEMENT ISSUE Times SERVING THE UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER COMMUNITY SINCE 1873 / campustimes.org ��� From its humble beginnings to the pomp and circumstance of today, UR's commencement ceremony has evolved into a ��� modern celebration still rich with UR tradition. ���� SEE COMMENCEMENT PAGE 7 Design by: Photos courtesy of rochester.edu and Antoinette Esce / Editor!in!Chief University of Rochester Archives PAGE 2 / campustimes.org NEWS / SATURDAY, MAY 18, 2013 COMMEN C EMENT CEREMONIES THE SCHOOL OF NURSING THE COLLEGE OF ARTS, SCIENCES & ENGINEERING FRIDAY, MAY 17, 1 P.M. THE scHOOL OF MEDICINE & DENTISTRY SUNDAY, MAY 19, 9 A.M. KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC MASter’S DEGREE EASTMAN QUADRANGLE, RIVER CAMPUS SATURDAY, MAY 18, 12:15 P.M. KILBOURN HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC THE EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC THE SCHOOL OF MEDICINE & DENTISTRY SUNDAY, MAY 19, 11:15 A.M. FRIDAY, MAY 17, 4 P.M. KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC THE MARGARET WARNER SCHOOL OF EDUCATION & HUMAN DEVELOPMENT SATURDAY, MAY 18, 2:30 P.M. THE WILLIAM E. SIMON SCHOOL DOCTORAL DEGREE CEREMONY KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION SATURDAY, MAY 18, 9:30 A.M. SUNDAY, JUNE 9, 10 A.M. KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC COLLEGE DIPLOMA CEREMONIES DEPARTMENT LOCATION TIME (SUNDAY) African American Studies Room 321, Morey Hall 2 P.M. American Sign Language Lander Auditorium, Hutchison Hall 1:15 P.M. Anthropology Lander Auditorium, Hutchison Hall 11:15 A.M. Archaeology, Technology & Historical Structures Sloan Auditorium 11:15 A.M. -

Magazine F a L L 2 0 0 7

MAGAzine F A L L 2 0 0 7 TRANSactions: Contemporary Latin AMERICAN AND Latino Art From the Director The Memorial Art Gallery, with its expansive collection of world art, has long offered temporary exhibitions that reflect the cultural and ethnic diversity of western New York. In recent years, we’ve showcased narrative paintings by American TRANSactions showcases political collisions and master Jacob Lawrence, treasures from Africa’s 40 works from the past two universal consequences.“ Kuba Kingdom, a sacred sand painting created by decades by artists from the A number of works present United States, Mexico, Cuba, Tibetan monks, and even, in Sites of Recollection, serious subjects in witty, Puerto Rico, Spain, Brazil, room-sized installations representing five distinc- sometimes humorous ways. Perry Colombia, Argentina and Chile. tive cultural traditions. Vasquez’s cartoonish Keep on By turns humorous and critical, Crossin’ (below) is a passionate inspirational and tragic, the This year we are pleased to present TRANSactions: manifesto and a charge to all exhibition seeks to dispel Contemporary Latin American and Latino Art, an individuals to continue crossing the myth that Latino artists exhibition that opened in San Diego, CA before borders of all kinds. Luis Gispert’s are a homogeneous group Wraseling Girls exploits viewers’ traveling to Rochester and Atlanta. We are proud with common experiences misconceptions about women, that Rochester will play a role in this significant and ambitions. national exhibition. Art that moves across and beyond And true to our goals of collaboration and diversity, we have established a year-long, com- geographical, cultural, political and munity-wide partnership showcasing the creativity and vision of contemporary Latin American and aesthetic borders is the subject of this Latino artists. -

Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Volume Ii

ACCOUNTING REFORM AND INVESTOR PROTECTION VOLUME II VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:39 Jul 17, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 87708V2.TXT SBANK4 PsN: SBANK4 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:39 Jul 17, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 87708V2.TXT SBANK4 PsN: SBANK4 S. HRG. 107–948 ACCOUNTING REFORM AND INVESTOR PROTECTION HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION VOLUME II ON THE LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF THE SARBANES-OXLEY ACT OF 2002: ACCOUNTING REFORM AND INVESTOR PROTECTION ISSUES RAISED BY ENRON AND OTHER PUBLIC COMPANIES MARCH 5, 6, 14, 19, 20, AND 21, 2002 Printed for the use of the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs ( VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:39 Jul 17, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 87708V2.TXT SBANK4 PsN: SBANK4 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:39 Jul 17, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 87708V2.TXT SBANK4 PsN: SBANK4 S. HRG. 107–948 ACCOUNTING REFORM AND INVESTOR PROTECTION HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION VOLUME II ON THE LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF THE SARBANES-OXLEY ACT OF 2002: ACCOUNTING REFORM AND INVESTOR PROTECTION ISSUES RAISED BY ENRON AND OTHER PUBLIC COMPANIES MARCH 5, 6, 14, 19, 20, AND 21, 2002 Printed for the use of the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 87–708 PDF WASHINGTON : 2003 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. -

Memorial ART Gallery of the University of Rochester

MEMORIAL ART GALLERY BIEnniaL REPort 2004–2006 OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER INAUGURATION OF PubLication ItaLian BaroQUE OF amErican Organ PAGE 1 cataLog PAGE 2 DIRECTOR’S TWEntiEth PAGE 1 STATISTICS FOR THE YEARS PAGE 2 EXhibitions PAGE 3 Programs anD EVEnts PAGE 5 giFts OF art PAGE 7 Donors, MEmbErs anD FriENDS PAGE 8 FinanciaL summary PAGE 14 boarD anD staFF BACK COVER EXTREME MATERIALS This 2006 EXhibition organiZED by thE MEmoriaL Art GALLEry shoWcasED non-traDitionaL WorKS by 35 nationaL anD intErnationaL artists. IN thE untitLED WorK abovE (DEtaiL shoWN), Washington, DC artist Dan STEinhiLBER turnED munDanE, mass-ProDucED DucK saucE PacKEts into A BEautiFUL, surPrisingLY SEnsuous WorK OF art. A E C B D F The Years in Review A Extreme Materials, organized by the C Summer 2005 saw the arrival at MAG E In May 2006, Grant Holcomb (arms Memorial Art Gallery, was the surprise hit of of the only full-size antique Italian organ in folded) arrives for a surprise celebration of the 2005-06 season. Over the show’s two- North America. The Baroque instrument, his 20th year as Gallery director. Surrounding month run, more than 27,000 people came from the collection of the Eastman School him are (from left) MAG Board president to see art created from such unorthodox sub- of Music, was permanently installed in the Stan Konopko, UR president Joel Seligman, stances as garden hoses, pencil shavings, fish Herdle Fountain Court, where it is surrounded Board member Friederike Seligman, daughter skins, carrots, rubber tires, eggshells, smog— by Baroque masterworks. Shown above is Devon Holcomb and son Greg Holcomb. -

Grant Holcomb, the Mary W. and Donald R

Public Relations Office · 500 University Avenue · Rochester, NY 14607-1415 585.276.8900 · 585.473.6266 fax · mag.rochester.edu NEWS HOLCOMB ANNOUNCES RETIREMENT FROM MEMORIAL ART GALLERY ROCHESTER, NY, NOVEMBER 19, 2013 — Grant Holcomb, the Mary W. and Donald R. Clark Director of the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, announced his retirement as director effective July 1, 2014. Holcomb noted that after an eventful year-long celebration of the Gallery’s 100th anniversary and the successful opening of Centennial Sculpture Park, the timing was right for him, as well as for the Gallery and the University. Board of Managers President Jim Durfee will lead a search committee charged with identifying a successor. Holcomb stated, “What more appropriate time to conclude my long tenure as director than after an extraordi- nary and exhilarating year-long celebration of the Gallery’s Centennial anniversary.” Holcomb, the sixth director in the Gallery’s long history, assumed the position in 1985 and over the course of three decades enhanced the Gallery’s permanent collections, broadened its exhibition programs and expanded the facilities. He led collaborations with cultural, educational and medical organizations that kept the Memorial Art Gallery an active leader for public engagement. “Grant has shaped the Gallery’s internal and external spaces and enhanced its collections in ways that will benefit art lovers for generations to come,” University President Joel Seligman said. Pete Brown, former President of the Board of Managers, recounts, “I had the pleasure of chairing the search committee that brought Grant to Rochester 28 years ago. We were struck then by his ability to share the art experience with everyone, regardless of background. -

0708 Annual Report.Pdf

Dear Friends: In 2009, the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra stands at an historic crossroads—looking back The 2007-08 season, which ended on August 31, 2008, We are proud to be leaders at the Rochester on a period of accomplishment governed by our last strategic plan and simultaneously looking was successful by most measures, but was also the most Philharmonic at this pivotal moment in its history. forward to the dual transformation of this organization and of our beloved home, the Eastman challenging of the past three years. Vacancies in more The Orchestra’s artistry and community support Theatre. The past year alone has been one of celebration and of progress, as we commemorated than a dozen administrative positions, including key have reached unprecedented levels, the Board and the 85th Anniversary of the RPO itself and celebrated Christopher Seaman’s 10th Anniversary leadership roles in Development and Marketing, slowed administration are strong and fully engaged, three-year Season as our gifted and greatly admired Music Director. the pace of growth in those areas, while unbudgeted contracts are in place for our musicians and our search and consulting expenses were incurred until conducting staff, and we are eagerly anticipating In short, we have a wonderful story to tell—one that we are thrilled to share with you. those positions were filled. These factors contributed the reopening of Kodak Hall at Eastman Theatre in It’s why we decided to transform our traditional Annual Report format into this broader to a deficit for the year of $162,000, or about 1.6% of October 2009 and the grand opening of the new wing Report to the Community. -

2010 George Eastman House Exhibitions

2010 George Eastman House Exhibitions What We're Collecting Now: Colorama The Family Photographed Curated by Jessica Johnston Curated by George Eastman House/Ryerson June 19–October 17 University Photographic Preservation & Collections Management students Jennie McInturff, Rick What We're Collecting Now: Art/Not-Art Slater, Jacob Stickann, Emily Wagner, and Andrew Curated by George Eastman House/Ryerson Youngman University Photographic Preservation & Collections September 5, 2009-July 18, 2010 Management students Jami Guthrie, Emily McKibbon, Loreto Pinochet, Paul Sergeant, D’arcy Where We Live White, and Soohyun Yang Curated by Alison Nordström, Todd Gustavson, July 24–October 24 Kathy Connor, Joseph R. Struble, Caroline Yeager, Jessica Johnston, and Jamie M. Allen Taking Aim: Unforgettable Rock ’n’ Roll October 3, 2009-February 14, 2010 Photographs Selected by Graham Nash October 30–January 30, 2011 How Do We Look Curated by Alison Nordström and Jessica Johnston All Shook Up: Hollywood and the Evolution of October 17, 2009-March 14, 2010 Rock ’n’ Roll Curated by Caroline Frick Page Roger Ballen: Photographs 1982–2009 October 30–January 16, 2011 Curated by Anthony Bannon February 27–June 6 Machines of Memory: Cameras from the Technology Collection Portrait Curated by Todd Gustavson Curated by Jamie M. Allen Ongoing February 27–October 17 The Remarkable George Eastman Persistent Shadow: Curated by Kathy Connor and Rick Hock Considering the Photographic Negative Ongoingz Curated by Jessica Johnston and Alison Nordström March 20–October -

INSIDE: the HISTORY of the MARSHALS Page 6 | Features a MESSAGE from PRESIDENT SELIGMAN Page 9 | Opinions the BEST of ATHLETICS Page 12 | Sports

CampusSUNDAY, MAY 17, 2015 / COMMENCEMENT ISSUE Times SERVING THE UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER COMMUNITY SINCE 1873 / campustimes.org INSIDE: THE HISTORY OF THE MARSHALS Page 6 | Features A MESSAGE FROM PRESIDENT SELIGMAN Page 9 | Opinions THE BEST OF ATHLETICS Page 12 | Sports In a photo originally taken in May 1953, Commencement Marshal and Professor of English George C. Curtiss walked toward Rush Rhees Library “toting mace for the last time.” Approximately 11 faculty members have been Commencement Marshal since 1935. PHOTO COURTESY OF ROCHESTER REVIEW AND RIVER CAMPUS LIBRARIES PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY AARON SCHAFFER / EDITOR-IN-CHIEF PAGE 2 / campustimes.org NEWS / SUNDAY, MAY 17, 2015 COMMENCEMENT CEREMONIES THE SCHOOL OF NURSING THE COLLEGE OF ARTS, SCIENCES & ENGINEERING FRIDAY, MAY 15, 1:00 P.M. THE SCHOOL OF MEDICINE & DENTISTRY SUNDAY, MAY 17, 9:00 A.M. KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC MASTER’S DEGREE EASTMAN QUADRANGLE, RIVER CAMPUS SATURDAY, MAY 16, 12:15 P.M. KILBOURN HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC THE EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC THE SCHOOL OF MEDICINE & DENTISTRY SUNDAY, MAY 17, 11:15 A.M. FRIDAY, MAY 15, 4:00 P.M. KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC THE MARGARET WARNER SCHOOL OF EDUCATION & HUMAN DEVELOPMENT SATURDAY, MAY 16, 2:30 P.M. THE WILLIAM E. SIMON SCHOOL DOCTORAL DEGREE CEREMONY KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION SATURDAY, MAY 16, 9:30 A.M. SUNDAY, JUNE 7, 10:00 A.M. KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC COLLEGE DIPLOMA CEREMONIES DEPARTMENT LOCATION TIME (SUNDAY, MAY 17) African and African-American Studies Gamble Room 2:00 P.M. -

GMF Program Journal 2015

Gateways Musi c Festi val IN AssOCIAtION WItH EAstMAN sCHOOL OF MusIC ProgrAm guide August 8-13, 2017 • ROCHEstER, NY Connecting and supporting professional classical musicians of African descent and inspiring and enlightening communities through the power of performance . Michael Morgan, Music Director & Conductor Lee Koonce, President & Artistic Director The Bienen School of Music offers · A new 152,000-square-foot state-of-the-art facility overlooking Lake Michigan · Conservatory-level training combined with the academic flexibility of an elite research institution · Traditional BM, BA, MM, PhD, and DMA degrees as well as innovative dual-degree, self-designed, and double-major programs · Close proximity to downtown Chicago’s vibrant cultural landscape 847-491-3141 www.music.northwestern.edu THE EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC and the GATEWAYS MUSIC FESTIVAL A Valued Partnership Since 1995, the Eastman School of Music has proudly joined the Gateways Festival in its mission of supporting professional classical musicians of African descent through the power of performance. TheThe EastmanEastmantman School of Music of the UniversityUniversity of RochesterRochester waswasas foundedfounded in 19192121 byby industrialistindustrialist GeorgeGeorge Eastman,Eastman,tman, is one of America’America’ss greatgreat music schools. Each yearyear its students,students, facultyfacultyaculty members, and distinguisheddistinguished guestguest artisartiststs presentpresent moremore thanthan 700700 concertsconcertserts and other eventsevents toto the RochesterRochester community.communityommunity. 1 GATEWAYS MUSIC FESTIVAL IN AssOCIAtION WItH EAstMAN sCHOOL OF MusIC BOARd OF dIRECtORs dR. P AuL BuRgEtt , C HAIRMAN FROM tHE PREsIdENt & ARtIstIC dIRECtOR Vice President & Senior Advisor to the President University of Rochester Rochester, NY JAMEs H. N ORMAN , V ICE CHAIRMAN welcome to the 2017 Gateways Music Festival! For 24 President & CEO Action for a Better Community (ABC) years, support from our community has enabled Gateways Rochester, NY to survive and thrive. -

Information Guide 2010–2012

Information Guide 2010–2012 Table of Contents Maps .........................................................................................................Inside Front Cover Administration ................................................................................................................... 1 Full-Time Faculty ................................................................................................................ 2 Adjunct Faculty ..................................................................................................................12 M.B.A. Requirements and Core-Course Charts ...................................................................16 Accelerated Professional M.B.A. Program ..........................................................................18 Concentrations—M.B.A. ...................................................................................................19 Master of Science Programs ...............................................................................................24 Joint- and Specialized-Degree Programs .............................................................................31 Courses .............................................................................................................................32 International Exchange Programs........................................................................................51 Admissions and Financial Aid .............................................................................................51 Student -

The New Kodak

President’s Page The New Kodak By Joel Seligman Eastman and Kodak touched nearly ev- ery corner of our University, funding the Eastman Kodak this month will emerge buildings early in the 20th century that from bankruptcy reorganization, a shadow allowed us to double our enrollment and of the company it once was. For over a cen- first award engineering degrees; creating tury, Kodak was Rochester; Rochester was the Eastman School of Music in 1921 along Kodak. Rarely has a company had such an with Eastman Theatre; endowing the East- indelible impact. man Dental Center in 1919 and then a few George Eastman was the Steve Jobs of years later, along with the Rockefeller Gen- his day. He popularized photography in eral Education Board and the Strong family, 1900 by creating the “Brownie” camera, helping create the School of Medicine and which made photography available to any- Dentistry and Strong Memorial Hospital. one who had a dollar and 15 cents for film, Eastman memorably led our 1924 Capital effectively taking photography out of the Campaign that enabled the University to exclusive hands of professional studios and establish and to expand many of our pro- putting it into the hands of millions of “am- grams on our current River and Medical ateurs.” Kodak’s yellow film boxes and dis- Center campuses. At Eastman’s death in tinctive graphic image were as ubiquitous 1932, he had given more money to the Uni- as the branded images of Coca-Cola or Ap- versity of Rochester than had been received ple continue to be today.