Mattawa/Ottawa River and Environs Historic Métis Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consolidated Municipal Services Managers and Areas Served

CONSOLIDATED MUNICIPAL SERVICES MANAGERS AND AREAS SERVED Consolidated Municipal Services Managers (CMSMs) in Southern Ontario provide a similar range of programs and services and also provide land ambulance and public health services with the approval of the Minister of Health. The role of the delivery agent in the provision of social services has progressed over time. The Local Services Realignment announced by the government in January 1997, outlined new directions for the delivery of social assistance, child care and social housing. These changes have created the opportunity to implement a more integrated system of social and community health services under municipal leadership. An integrated system is one in which policies; programs and services are coordinated and complementary and serve common goals that address the well being of individuals, families and communities. Consolidation of municipal service management has resulted in the management of the delivery of social assistance, child care, and social housing by 36 municipalities in Southern Ontario and by 10 District Social Services Administration Boards as well as the Regional Municipality of Sudbury in Northern Ontario. Authority to require consolidation of municipal service management is provided by the Services Improvement Act and the Social Assistance Reform Act. In Northern Ontario, ten District Social Services Administration Boards (DSSABs) and the Regional Municipality of Sudbury were approved as CMSMs. DSSABs are responsible for serving both municipalities and territories without municipal organization. The nine southern Ontario regional municipalities plus the City of Toronto are, by legislation, boards of health for their region, as well as CMSMs. [Please refer to attached chart outlining Consolidated Municipal Service Managers - Ontario Works, Child Care and Social Housing -- area served in Southern and Northern Ontario] 1 Consolidated Municipal Service Managers Ontario Works, Child Care and Social Housing Service Manager Area Served SOUTHERN ONTARIO 1. -

37131055428965D.Pdf

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF CANADA. REPORT OF PROGRESS FOR THE YEAR 1845-6 . .:t1rlontnaI ! LOVELL & GIBSON, PRINTERS, SAINT NICHOLAS STREET. 1847. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF CANADA. REPORT OF PROGRESS FOR THE YEAR 1845-6. MONTRE;\L, 1st May, 1846. SIR, I have the honor to transmit to YOll the accompanying Report of the Progress made in the Geological Survey of the Province, in the year lS45-G, ,mel request you will do me the favor to place it bei()[e His ExceIlel1c.I', the Governor General. I have the honor to be, Sir, Your most obedient humble servant, W. E. LOGAN, PrOt'incia/ GeolofJi.t. To the llollorau]e D. Daly, Pro1'inciai Secretar!). &c. &c. TO HIS EXCELLENCY LIEUTENANT GENERAL THE RIGHT HONORABLE CHARLES MURRAY, EARL CATHCART, OF C_UHCAI,r, l~ rilE conuy OF RENFREW, K. C. B., GOVERNOR GEKERAL OF BRITISH ~~ORTII AMERICA, AND C.\PTAIN-GENERAL A::-lD GOVERNOR-IN-CHIEF 1:" A~D OYER THE PRonNCES OF CANADA, NOVA SCOTIA, NEW BRUNSWICK, AND THE ISLAND OF PRINCE EDWARD, AND VICE-ADlI1IRAL OF THE SAME, Sec. &0. &0. MONTREAL, 1st May, 1846. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR EXCELLENCY, In conformity with my duty as Director of the Geological Sur vey of the Province, I have the honor to place before Your Excel lency, a Report of the Progress made in the investigation during the past summer. In reporting to the Government on the Progress made in the year 1843, a short and very general sketch was gi\"en of some of the main geological features of a considerable part of the Province, as connected with the physical structure of the bordering States of the American Union on the one hand, and the Sister British Colonies, on the other. -

Temagami Area Rock Art and Indigenous Routes

Zawadzka Temagami Area Rock Art 159 Beyond the Sacred: Temagami Area Rock Art and Indigenous Routes Dagmara Zawadzka The rock art of the Temagami area in northeastern Ontario represents one of the largest concentrations of this form of visual expression on the Canadian Shield. Created by Algonquian-speaking peoples, it is an inextricable part of their cultural landscape. An analysis of the distribution of 40 pictograph sites in relation to traditional routes known as nastawgan has revealed that an overwhelming majority are located on these routes, as well as near narrows, portages, or route intersections. Their location seems to point to their role in the navigation of the landscape. It is argued that rock art acted as a wayfinding landmark; as a marker of places linked to travel rituals; and, ultimately, as a sign of human occupation in the landscape. The tangible and intangible resources within which rock art is steeped demonstrate the relationships that exist among people, places, and the cultural landscape, and they point to the importance of this form of visual expression. Introduction interaction in the landscape. It may have served as The boreal forests of the Canadian Shield are a boundary, resource, or pathway marker. interspersed with places where pictographs have Therefore, it may have conveyed information that been painted with red ochre. Pictographs, located transcends the religious dimension of rock art and most often on vertical cliffs along lakes and rivers, of the landscape. are attributed to Algonquian-speaking peoples and This paper discusses the rock art of the attest, along with petroglyphs, petroforms, and Temagami area in northeastern Ontario in relation lichen glyphs, to a tradition that is at least 2000 to the traditional pathways of the area known as years old (Aubert et al. -

Temagamite Pd3hgte3 C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1

Temagamite Pd3HgTe3 c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Orthorhombic. Point Group: n.d. As rounded to irregular inclusions, to 115 µm, in chalcopyrite. Physical Properties: Hardness = n.d. VHN = 92 (25 g load). D(meas.) = 9.5 (synthetic). D(calc.) = 9.45 Optical Properties: Opaque. Color: In polished section, white with a gray tinge. Luster: Metallic. Anisotropism: Weak in air, stronger in oil, in pale gray to dark gray. R1–R2: (470) 51.8–52.8, (546) 52.9–53.9, (589) 54.2–55.0, (650) 57.1–57.7 Cell Data: Space Group: n.d. (synthetic). a = 11.608(2) b = 12.186(1) c = 6.793(1) Z=6 X-ray Powder Pattern: Synthetic. 2.912 (10), 2.187 (9), 1.959 (7), 1.661 (5), 1.624 (5), 1.462 (5), 1.155 (5) Chemistry: (1) (2) Pd 34.9 34.5 Pt 1.0 Hg 22.1 22.0 Bi n.d. 0.13 Te 42.1 42.1 Total 99.1 99.73 (1) Temagami Mine, Canada; by electron microprobe, corresponding to Pd2.99Hg1.00Te3.01. (2) Stillwater complex, Montana, USA; by electron microprobe, corresponding to (Pd2.95Pt0.05)Σ=3.00Hg1.00Te3.00. Occurrence: Cogenetic with moderately high-temperature invasive chalcopyrite magma (Temagami Mine, Canada). Association: Merenskyite, hessite, chalcopyrite, st¨utzite. Distribution: In Canada, in Ontario, from the Temagami Cu–Ni mine, Temagami Island, Lake Temagami, Nipissing district [TL] and from a prospect near Rathbun Lake. In the USA, from the Stillwater complex, Montana; and the New Rambler Cu–Ni mine, Medicine Bow Mountains, east of Encampment, Albany Co., Wyoming. -

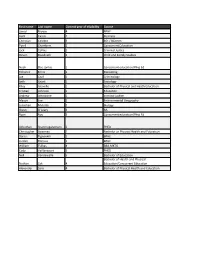

Nipissing District Contact Colours School Persons Team Name Classification

2016-2017 N.O.S.S.A. - MEMBER SCHOOLS' DIRECTORY Page 1 NIPISSING DISTRICT CONTACT COLOURS SCHOOL PERSONS TEAM NAME CLASSIFICATION 1. E.S.C. Algonquin (NOAL) Tim Lowe Maroon/White 555 Algonquin Avenue Pat Lalonde Barons North Bay, Ontario P1B 4W8 "A" Ph. 472 8240 FAX 472-8476 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 2. E.S. Franco-Cite (NOFC) Rock Lachance Orange/Black/ 90 Rue Main Brigitte Marleau White Sturgeon Falls, Ontario P2B 2Z7 Patriotes Ph. 753-1510 FAX 753-5370 “A” Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 3. Chippewa Secondary School (NOCW) Dez Forget Scarlet/Gold 539 Chippewa St. W. Raiders North Bay, Ontario P1B 6G8 "AA" Ph. 475-2341 ext 5 FAX 476-0845 Email: [email protected] 4. E.S.C. Élisabeth-Bruyère (NOEB) Kareena Lindsay Purple/Grey/Black 359, rue Brydges, C.P. 1010 Loups Mattawa, Ontario. P0H 1V0 "A"/”B” Ph. 744-5505 Email: [email protected] 5. F.J. McElligott (NOME) Scot Quarrington Blue/Gold 370 Pine Street Voyageurs Mattawa, Ontario. P0H 1V0 "A"/”B” Ph. 472-5720 FAX 744-0786 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 6. E.S. Northern SS (NONO) Daniel Stevens Silver/Red 175 Ethel Street Braves Sturgeon Falls, Ontario P2B 2Z8 "A" Ph. 472-5322 FAX 753-2400 Email: [email protected] Northern Ontario Secondary School Athletics (N.O.S.S.A.) 2016-2017 N.O.S.S.A. - MEMBER SCHOOLS' DIRECTORY Page 2 NIPISSING DISTRICT (cont’d) CONTACT COLOURS SCHOOL PERSONS TEAM NAME CLASSIFICATION 7. -

First Name Last Name Current Year of Eligibility Course Jamal Brown 4

First name Last name Current year of eligibility Course Jamal Brown 4 BPHE Liam Cassis 1 Business Christian Celebre 3 BSc / BComm Tyrell Chambers 2 Concurrent Education Jack Collins 2 Criminal Justice Deven Doodnath 2 Child and Family Studies Noah Dos santos 1 Concurrent education/Phys Ed Yohance Ennis 2 Marketing Joe Graf 1 Criminology Seth Grant 1 Sociology Riley Gravelle 1 Bachelor of Physical and Heath Education Kristian Johnson 1 Education Andrew Johnstone 1 criminal justice Mason Lee 2 Environmental Geography Jonathan Mulimbi 2 Biology Owen O'Leary 3 BA Ryan Roy 3 Concurrent education/Phys Ed Achuthan Shanmugaratnam 2 PHED Christopher Sweeney 2 Bachelor or Physical Health and Education Darius Tignanelli 1 BPHE Jordan Titmuss 1 BPHE William Tsilkas 4 BBA.MKTG Cody Vaillancourt 3 PHED Neil Vandewalle 5 Bachelor of Education Bachelor of Health and Physical Nathan Zak 4 Education/Concurrent Education Alexander Zero 4 Bachelor of Physical Health and Education Year of study Home town Home province Last team 4 Barrie ON Nipissing Lakers (OUA) 1 North Bay ON Fiorentina FC OCSL 3 North Bay ON Nipissing Lakers (OUA) 3 Brampton ON CAF League 2 Ottawa ON OSU 3 Toronto ON Toronto Skillz FC, League1 Ontario Parkside soccer (tvdsb), Parkside volleyball (tvdsb), Parkside hockey (tvdsb), Croatia men's 1 St Thomas ON premier 2 toronto ON Toronto Skillz fc League One 1 North Bay ON St Anthony’s Soccer Club 1 North Bay ON Ottawa South United, League 1 Ontario 2 North Bay ON Widdifield S.S. 1 North Bay ON Carleton Place Soccer Club, ERSL 3 Barrie ON algoma University 2 Innisfil ON Bradford Wolves FC 3 Ottawa ON Nationwide School For Academic Excellence 4 Mitchell ON FC London & League 1 3 Barrie ON Nipissing Lakers (OUA) Pope John Paul II Catholic Secondary School: 2 Scarborough ON Men's Soccer, Ultimate Frisbee, Swimming 2 North Bay ON David FC, North Bay Men's League 4 NORTH BAY ON Nipissing District Mens Soccer 1 NORTH BAY ON fogo fc soccer 4 Richmond Hill ON markham lightning 3 North Bay ON Nipissing Lakers (OUA) 6 St. -

TEMAGAMI New Protests Ovec Old Growth

7-;,. i FOR REFERENCE NOT TO Br TAKITN FPOM THIS ROOM iW/^.-r.,^ Ct Cetera <..J j ? .; ¥.-5 ^..- ¥ i ? »., «... i S-' « i ;iV,.U:l...:,,.2 5:Sj>S;U K*s \'-':- •!«. «* / TEMAGAMI New protests ovec old growth. Story and pictures • page 3 '^', ^^;:'.h i !ai9KS««B»5*i!J»>^ *%*-jM«(«i9iuge L- ^V Women beat George Brown but A'^P Men's team lose first game in over a year "page I 7 and 18 • Into th^e Explosion page I 3 > £t Cetera talks to Jon Spencer Blues Explosion's Judah Bauer iv#ai-'f law" aiBts'-avt Pemianent Drug Mart CampusZ ^'i conveniently locaM h the Biwajr Flaza right across H«y 27 from Humber (^^ Computer \\r hiinour tlu' I olliiif I),i\-diRHi ilnii^ i)l.in Shop 4I&74&4212 or Fte 41&745«213 • 106 Hundicr Cdkge Bkd, RaoUe Seetheoffer|Qa.DaQe4 V IlltMii^Pft' COLLCQE "m<,r. iiiiii . fin:.,: titommg SAC on protest SAC president unsure if council will participate in Days ofAction -'.• '; by Cheryl Waugh--y'^-^-v i LiborlUportw While student governments across the province are gearing up for the Metro Days of Action protests later this month, Number's North Campus Students' Association Council has- Stand Up n't decided if it will participate. SAC President Steve Virtue said Speak Out the council hasn't formed an opin- ion yet as to which stance the/ll Be Heard be taking in a joint labor and com- munity protest set for the week of Oct 21-26. *The Brewers "I think there are other things Steve Virtue said ite is cautious alxMit the protest because he is umure how students will respond to it Assocmm ofCanada that we can do that are more slon." McCracken. -

Rank of Pops

Table 1.3 Basic Pop Trends County by County Census 2001 - place names pop_1996 pop_2001 % diff rank order absolute 1996-01 Sorted by absolute pop growth on growth pop growth - Canada 28,846,761 30,007,094 1,160,333 4.0 - Ontario 10,753,573 11,410,046 656,473 6.1 - York Regional Municipality 1 592,445 729,254 136,809 23.1 - Peel Regional Municipality 2 852,526 988,948 136,422 16.0 - Toronto Division 3 2,385,421 2,481,494 96,073 4.0 - Ottawa Division 4 721,136 774,072 52,936 7.3 - Durham Regional Municipality 5 458,616 506,901 48,285 10.5 - Simcoe County 6 329,865 377,050 47,185 14.3 - Halton Regional Municipality 7 339,875 375,229 35,354 10.4 - Waterloo Regional Municipality 8 405,435 438,515 33,080 8.2 - Essex County 9 350,329 374,975 24,646 7.0 - Hamilton Division 10 467,799 490,268 22,469 4.8 - Wellington County 11 171,406 187,313 15,907 9.3 - Middlesex County 12 389,616 403,185 13,569 3.5 - Niagara Regional Municipality 13 403,504 410,574 7,070 1.8 - Dufferin County 14 45,657 51,013 5,356 11.7 - Brant County 15 114,564 118,485 3,921 3.4 - Northumberland County 16 74,437 77,497 3,060 4.1 - Lanark County 17 59,845 62,495 2,650 4.4 - Muskoka District Municipality 18 50,463 53,106 2,643 5.2 - Prescott and Russell United Counties 19 74,013 76,446 2,433 3.3 - Peterborough County 20 123,448 125,856 2,408 2.0 - Elgin County 21 79,159 81,553 2,394 3.0 - Frontenac County 22 136,365 138,606 2,241 1.6 - Oxford County 23 97,142 99,270 2,128 2.2 - Haldimand-Norfolk Regional Municipality 24 102,575 104,670 2,095 2.0 - Perth County 25 72,106 73,675 -

5.2 a History of Mattawa

OTTAWA RIVER COMMUNITY HERITAGE 215 5.2 A History of Mattawa Mattawa Heritage Designation Committee The word Mattawa comes from Matonawang, meaning the meeting of the waters.1 Mattawa is located at the crossroads of a vast water highway that opened up the country. Mattawa was at the centre of the routes taken by Aboriginal Peoples, European explorers, missionaries, fur traders, loggers, miners, and settlers wishing to access central, western and northern Canada. The Mattawa Area under New France When early French explorers like Champlain and Lasalle moved up the Ottawa River and into the interior of the continent via the Mattawa River, they thought they would find a way to the Pacific and on to China. Many of the early French explorers who traveled through the Mattawa area were accompanied by Recollet and Jesuit priests who came to convert the Algonquin, Nipissing and Huron peoples to Christianity. The Jesuits established a major mission at Sault‐Saint‐Marie among Huron peoples, and accessed Huronia via Mattawa. The waterway also served as a communication link between Huronia and Jesuit missions on the St. Lawrence River. The French soon became involved in fur trading. The earliest fur trading post near our area was established by the French in 1679 on an island where the Montreal and Matabitchuan Rivers flow into Lake Temiskaming. In the late 1600s, the post was moved across the river and Fort Temiskaming was established near Ville Marie, Quebec. Since the fur trade in New France was based in Montreal, Ottawa River navigation routes through the Mattawa area were of strategic importance in the movement of trade goods inland and furs down to Montreal. -

S T a R T F I N I

Lac la Cave «¬63 ¯ «¬533 S Lac la Cave F MATTAWA RIVER PROVINCIAL PARK (WATERWAY CLASS) Mattawa T SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN I Checkpoint 1 Island PROVINCIAL PARK Chant Portage Checkpoint 3 Plain Lake Olmsted Pin de Family Race Beach A Trout Lake Musique Lake Talon Les Epingles N See enlargement below Portage Laurier Elks Lodge P Start! IN (lac Talon) Portage Woods 25 Family E Portage des ChantPlain Turtle Lake L Park Portage A K Paresseux Portage Campion (Hurdman Dam) E Shields Portage de Portage (lac Tortue) de la Mauvaise R McLaren R D la Prairie Portage de des Roches I La Vase Musique la Cave Portage Unnamed Portage Eva Portage des Perches Wardlaw T de Talon S Park 17 Pimisi Bay «¬ Eau Corbeil Checkpoint 2 Claire Gorge AWARDS BANQUET LOCATION: AMABLE DU FOND RIVER PROVINCIAL PARK Mike Rodden Community Centre H (WATERWAY CLASS) 11 94 «¬ «¬ 450 Hurdman Street Lake Nipissing Mattawa, ON P0H1V0 (lac Nipissing) Tel: (705) 744-2311 CALLANDER BAY WETLAND CONSERVATION RESERVE Callander Bay Papineau Lake Nosbonsing (lac Nosbonsing) BOULTER-DEPOT CREEK Lake CONSERVATION 0 1.25 RESERVE 2.5 5 Kilometers Papineau Lake Legend Inset Map Portage des Paresseux This publication was produced by: Portage Watercourse North Bay-Mattawa Conservation Authority, 15 Janey Avenue, North Bay, ON P1C 1N1 Waterbody Telephone: (705) 474-5420 Portage de la Prairie Dinner Location Data supplied under Licence by Members of the Ontario Geospatial Data Exchange. Conservation Area Portage de la Cave Canoe Route © 2016 NBMCA Unnamed Conservation Reserve This map is illustrative only. Do not rely on it as being a precise indicator of routes, location of features, nor as a guide to navigation. -

Looking for a Boiler Supply & Servicing Company with The

Service Area Volume 49 • June 2017 South West tel: 519 884 0600 505 Dotzert Court, fax: 519 884 0213 Unit 1 toll free: 1 800 265 8809 Waterloo, ON N2L 6A7 www.waterloomanufacturing.ca East tel: 613 228 3597 19 Grenfell Crescent, Bay 1 fax: 613 225 0116 Ottawa (Nepean) ON toll free: 1 800 265 8809 K2G 0G3 www.waterloomanufacturing.ca Looking For A Boiler Supply & Servicing Company With The Knowledge & Experience To Get It Right? We are that company and we want to help you optimize your boiler room. Established in 1850, Waterloo Manufacturing Ltd. has a long history of growth and evolution that continues to this day. In our early days we began as a manufacturer of farm machinery equipment, steam engines, pulp and paper rolls, and in 1947, became an authorized Cleaver Brooks Representative for South West Ontario. In 1984, we streamlined the company to further focus on solely providing boiler room equipment solutions in South West Ontario. In 2015, a unique opportunity arose to expand our company to include the Eastern Ontario region formerly covered by John M. Schermerhorn Ltd. In 2017, a further opportunity arose to expand our company to include the territory formerly represented by Johnson Paterson, Inc. to be the sole representative for Cleaver Brooks in the province of Ontario. *Refer to Map on Page 4. Ontario West Central Ontario Ontario East • Brant County • Algoma District • Carleton County • Bruce County • Cochrane District • Dundas County • Dufferin County • Durham County • Frontenac County • Elgin County • Haliburton County • Glengarry -

IBM's Watson Goes to Law School

THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO FACULTY OF LAW ALUMNI MAGAZINE SPRING/SUMMER 2015 IBM’s Watson goes to law school Can artificial intelligence @BlueJLegal make legal research easier? AT THE BORDERS OF CITIZENSHIP Report exposes Canada’s legal ‘black holes’ when dealing with mentally ill migrants REAL TIME, RESPONSIVE, REVEALING Straight-talk legal analysis on antiterrorlaw.ca bared Bill C-51 's ambiguities AGENTS OF CHANGE A curriculum tool aims to teach youth their legal rights—to stand up against forced marriage PLUS CONVOCATION COVERAGE! “ Education is a great source of success in society and satisfaction in life.” Michael McSorley JD 1977 The strategies and expertise Michael McSorley gained at law school served him well throughout a stellar career in Canadian mining. His goal now is to give deserving students the same advantage. That’s why he established the McSorley Scholarships for graduate studies in law. Leave a gift in your will to the Faculty of Law and you too can support the next generation of legal minds. Your bequest is a meaningful way to join the Faculty’s Boundless campaign. Find out more: [email protected] 416-946-8227 [email protected] 416-978-3846 DEAN’S MESSAGE Spring/Summer 2015 Volume 25, Number 1 EDITOR IN CHIEF Chantelle Courtney, LLB EXECUTIVE EDITOR Lucianna Ciccocioppo ART DIRECTOR Katina Constantinou, Sugar Design COPY EDITOR Dylan Reid FACT CHECKERS Martha Beach Catherine Dowling PHOTO BY RAINA + WILSON + RAINA BY PHOTO Sarah B. Hood MAILING ASSISTANT Six months in Nancy Reid Tel: 416 978 1355 Fax: 416 978 7899 It’s been a fascinating journey since starting as dean in January.