Fire and Form: Masters of Clay and Glass June 12 - July 5, 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fiberclay.Pdf

Sculpting a Creature with Fiber Clay By Brant Palley, New Mexico Clay (Grade Level: High School) Objectives: The Student will learn about fiber clay construction, we will experience the advantages of Fiber clay (sheepdog Cone 04) over regular clay and over more traditional paper clay; we will construct a creature from premade, bone dry, body parts. The assembly is with slip and wet clay. The classroom advantages are obvious, you don’t have to worry if the sculpture (or coiled pot) has dried out because you can add on, and even cut off! You can get a project done in 30 minutes. Read more on www.fiberclay.com Learn of Rosette Gault and Graham Hay from Australia. Use the slip and denture cream method of attaching bone dry to bone dry clay pieces together that holds together adequately. Materials: • Pre made pieces (legs, arms, necks…) • 2- lbs orange sized pieces of clay per student • Water container for slip • Plastic Forks, Tongue Depressors, Cloth for covering tables. • Sheepdog Fiberclay from New Mexico Clay References: Present visuals of Artwork by artists such as Rosette Gault and Graham Hay. Rosette Gault http://www.paperclayart.com/ Graham Hay. http://www.grahamhay.com.au/ Discuss the medium clay, what it is made of and introduce clay vocabulary words such as fire, kiln, and paper clay. Procedure: Demonstrate how to attach bone dry clay to both bone dry clay and wet clay using the slip and denture cream method. Paint slip on all surfaces to be bonded, take a small piece of wet clay and wet it with slip, smush everything together. -

Mini Catalog

CLAY ART CENTER MINI CATALOG CLAY ART CENTER 2636 Pioneer Way East Tacoma Wa 98404 800-952-8030 Fax 253-922-5349 www.clayartcenter.net AUG 25, 2020 CLAY ART CENTER 2636 Pioneer Way East Tacoma WA 98404 1-800-952-8030 Fax 1-253-922-5349 1 CLAY DESCRIPTIONS CONE 06 CLAYS is widely used for vitreous tiles fired at cone 4 to 6 and is also used in outdoor installations where freezing is a con- CL 027 COLEMAN RAKU cern. A fine tooth throwing body with kyanite grog. Will resist firing stress and gain in strength as the mullite develops. The clay will fire as hot as cone 10 and retain its off white color. CONE 4-6 CLAYS CL 141 AKIO SCULPTURE CL 126 COLEMAN RAKU GROG A heavy grogged clay that is excellent for large sculpture. A throwing body with larger kyanite grog. Will resist firing Brown in reduction, fires to cone 6. stress and gain in strength as the mullite develops. The clay will fire as hot as cone 10 and retain its off white color. CL 140 ARLEO Thin chopped nylon fiber adds stength to this medium CL 171 HUSKY WHITE smooth clay. Perfect for difficult sculpture work. Light tan, Husky White is a low fire white earthenware body with fine fires to cone 6. sand. Ideal for throwing and handbuilding. CL 108 BC6 CL155 HUTCHINS RAKU A great throwing, white, stoneware. Very smooth and plastic, Great throwing smooth raku body, light color with good crack excellent glaze fit. Gray to off-white in oxidation. -

Holds the Key Ingredient... Contents

2016 holds the key ingredient... Contents About Us 3 How To Choose The Right Clay For You 4 Our Clays 6 Terracotta 6 Alex Shimwell Stoneware 7 Earthstones 10 Professional 13 Porcelain 16 Earthenware 17 French Regional Clays 18 Paper Clays 18 Powdered Clays 19 Slips 21 Casting Slips 21 Pouring Slips 21 Decorating Slips 21 Raw Materials 22 China/Ball Clays 22 Raw Clays 22 Fluxes 22 Oxides 23 Groggs 23 Plasters 23 Deflocculants 23 Sundry Materials 24 Custom Clay Formulas & Special Order Clays 25 Warranties & Responsibilities 25 Technical Information 26 Jane Wheeler 2016 Price List 30 Distributors 34 Front cover images are provided by... Top: Clare Wakefield Bottom: Beverley Gee, Garry & Pollie Uttley, Susanne Luckacs-Ringel 2 INFO About Us In the heart of the potteries over the past 36 years over 90 clay bodies to choose from Valentine Clays has Valentine Clays, a family run manufacturer, has worked ensured that there is a product to suit a potters every directly with the studio potter community formulating need whether you are a beginner or a professional. and fine tuning clays using the best possible ingredients. For advice or help with any technical issues please call This close working relationship enables the world-leading 01782 271200 or email [email protected] clay manufacturer and raw materials supplier; based we will be only too pleased to help. in Stoke-on-Trent, to successfully develop ceramic clay bodies to suit the specific requirements of a long list of renowned British and International potters. The team at Valentine Clays prides itself on constant development of new and innovative clays bodies using Kind regards, the latest ceramic manufacturing equipment; with The Valentine Clays Team Thank you to the studio potters whose images, taken from our online gallery, have been used in this brochure. -

MY EXPERIENCE ABOUT PAPER KILNS SINCE 2007 Mutlu Baskaya(Turkey)

MY EXPERIENCE ABOUT PAPER KILNS SINCE 2007 Mutlu Baskaya(Turkey) Picture 1: 1st Poster of paper kiln workshop, 2007 Picture 2: One year later-poster of paper kiln workshop exhibition, 2008 I have constructed my experimental paper kilns in Turkey and in abroad since 2007. My paper kilns are designed in the logic of wood firing kilns with a firebox below stoked by wood. And at first wire net is covered with paper clay and then with newspaper dipped in clay. These are my kiln’s features. Other artists do not stoke the fire like wood firing kilns and they do not use the paper clay while they are constructing their kilns. So after firing, their kilns are collapsed. I learned paper kiln technique for the first time in 1994 at the paper kiln workshop held under the leadership of Yugoslavian artist BIZJAK ZVONKO in GIOELA SUARDI’s studio in Italy but that kiln had been constructed by a different technique and had been smaller than mine. My 1st paper kiln workshop was held on the occasion of 40th anniversary of Hacettepe University and 25th anniversary of Faculty of Fine Arts on 19 May 2007 at H.U. Beytepe Campus under the leadership of me with the attendance of 100 people from academic staff and students of Ceramics, Sculpture, Paintings, Interior Design and Graphics Design Departments of Hacettepe and 9 Universities (Picture 1,2,3,4). 1 I did many paper kiln workshops in Turkey and abroad. Countries where I constructed my paper kilns were Turkey, India, Thailand. I used many kind of clay to mix with paper pulp. -

Specialty Mix P'clays for Ultra Large Projects

Specialty Mix P’Clays “Rosetta Stone” Texture after fi re: Smooth, white, the higher you Earthenware Paper Clay for Sculpture fi re it, the more dense and hard it gets until after for Ultra Large Projects Cone 04 to 4 normal (maximum cone 6) cone 4. Two (2) medium buckets (use same Low fi re texture- Cone 03 to 04:Too hard to If you are not sure where to start, size buckets to measure this) prepared carve on by hand, but power tool is OK. Can treat adapt my personal recipes for life scale “earthenware” base (rated cone 04-05). It can surface with any and all commercial glazes, opaque freestanding and wall works given here. be simply buckets of prepared casting slip. or transparent underglazes, overglazes, etc, and refi re Test fi re, I cannot be responsible for non- One (1) medium bucket-same size of wet if desired. Normal slips, engobes, stains OK. At this temperature, the result is a soft normal earthenware. standard materials, events and results strained bulk of pulp- plus or minus handfuls and inches. Dispersed paper from 8-12 Vessel will seep water without a fi nish gloss glaze or clearly beyond my control. I recycle my rolls of “bargain” toilet tissue is equivalent other seal. paper, but I have indicated volumes of to maybe 8 bulkier rolls of deluxe brands, Mid Range (Cone 4 to 6): Hard as a rock. pulp by standard toilet roll to help the but donʼt try to make this pulp in this same Resembles white stoneware. Resists water but may student with a starting point. -

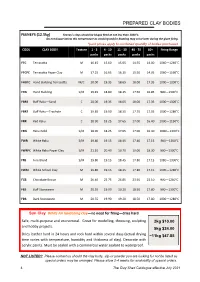

Prepared Clay Bodies

PREPARED CLAY BODIES FEENEYS (12.5kg) Feeney’s clays should be bisque fired at not less than 1020°C. Do not bisque below this temperature as cracking and/or bloating may occur later during the glaze firing. *pack prices apply to combined quantity of bodies purchased CODE CLAY BODY Texture 1 - 3 4 - 10 11 - 39 40 - 79 80+ Firing Range packs packs packs packs packs FTC Terracotta M 16.15 15.60 15.05 14.55 14.00 1060—1240°C FTCPC Terracotta Paper Clay M 17.25 16.65 16.10 15.50 14.95 1060—1160°C FHBTC Hand Building Terracotta M/C 20.00 19.35 18.65 18.00 17.35 1000—1200°C FHB Hand Building S/M 19.45 18.80 18.15 17.50 16.85 900—1300°C FBRS Buff Raku—Sand C 20.00 19.35 18.65 18.00 17.35 1000—1300°C FBRT Buff Raku—Trachyte C 19.65 19.00 18.35 17.70 17.05 1000—1280°C FRR Red Raku C 18.90 18.25 17.65 17.00 16.40 1000—1150°C FRG Raku Gold S/M 18.90 18.25 17.65 17.00 16.40 1080—1300°C FWR White Raku S/M 19.80 19.15 18.45 17.80 17.15 900—1300°C FWRPC White Raku Paper Clay S/M 21.10 20.40 19.70 19.00 18.30 900—1300°C FFB Fine Blend S/M 19.80 19.15 18.45 17.80 17.15 1080—1300°C FWSC White School Clay M 19.80 19.15 18.45 17.80 17.15 1000—1280°C FCB Chocolate Brown M 26.65 25.75 24.85 23.95 23.10 900—1240°C FBS Buff Stoneware M 20.55 19.90 19.20 18.50 17.80 900—1300°C FDS Dark Stoneware M 20.55 19.90 19.20 18.50 17.80 1000—1280°C Sun Clay White Air hardening clay—no need for firing—dries hard Safe, multi-purpose and economical. -

Paper-Composite Porcelain

Paper-Composite Porcelain: Characterisation of Material Properties and Workability from a Ceramic Art and Design Perspective Paper-Composite Porcelain: Characterisation of Material Properties and Workability from a Ceramic Art and Design Perspective Jeoung-Ah Kim The School of Design and Crafts HDK (Högskolan för Design och Konsthantverk) at the Göteborg University Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Design at School of Design and Crafts, Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts, Göteborg University ArtMonitor is a publication series from the Board for Artistic Research (NKU) of the Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts, Göteborg University Publisher: Johan Öberg Adress: Art Monitor, Göteborgs universitet Konstnärliga fakultetskansliet Box 141, SE-405 30 Göteborg, Sweden www.konst.gu.se Designed and typeset by Sara Lund, Anna Frisk and the Author Swedish translation by Cecilia Häggström Photographs by: Jeoung-Ah Kim Cover: Right above: Figure 1 of Paper I. Paper-composite porcelain (MCP 3) fired at 1300oC. Mullite, α-quartz, anorthite and amorphous materials are formed during batch composition. Left above: Figure 5 of Paper I. The SEM image of paper-composite porcelain (MHP1) fired at 1260oC. Fibrous structures display binding and an interlocking of the fibres, and construction of fibrous bridging. Below: Figure 1 (b) of Paper III. A model produced with MCP 3 by the slip casting method and fired at 1300oC. A transparent glaze was applied. The image was photographed by Jeoung-Ah Kim and the layout designed by Cecilia Häggström. Printed by Elanders, Mölnlycke 2006 © Jeoung-Ah Kim, 2006 isbn: 91-975911-2-2 To my parents, and my son Peter List of Papers This doctoral thesis is based on the following four papers, which are referred to by the Roman numerals as shown below: Paper I Jeoung-Ah, K. -

Toronto Potters 16Th Biennial Exhibition Catalogue

TORONTO POTTERS 16TH BIENNIAL EXHIBITION www SEPTEMBER 6 - 30 . 2102 ONTARIO CRAFTS COUNCIL GALLERY 1 2 TORONTO POTTERS 16TH BIENNIAL EXHIBITION www SEPTEMBER 6 - 30 . 2012 ONTARIO CRAFTS COUNCIL GALLERY 3 16 4 CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS Lindsay Anderson Barbara Banfield Eden Danielle Bender Celia Zveibil Brandao Alison Brannen George Cho Chari Cohen Aliza Hosiosky Deborah Freeman Judith Graham ShaKed Kaplan Yumiko Katsuya Renee Kleiman Irit Lepkin Kathleen Matsushita Lesley McInally Heidi McKenzie Mary McKenzie Judith Morsink Abbey Smith Nebojsa Stojkovic 5 6 INTRODUCTION Toronto Potters is a Through Toronto Potters, members have technical merit, originality and cre- artists and seven awards presented for a platform to share their skills, as well ative expression. Through the public outstanding work. non-profit association as stimulate and foster their individual diplay of work, accompanied by a print with a member dedication interests in working with clay. catalogue, the biennial juried exhibition This catalogue is a representation of the is an esteemed opportunity for members myriad ways in which the ceramic ma- that has run its programing Members benefit from monthly meetings, to showcase their creative skills. terial can be manipulated, as well as the for over 33 years. presentations and demonstrations, as well commitment and passion with which as retail shows and a website that The Biennial Juried exhibition, now in its these objects have been conceived and It consists of approximately showcases their work. 16th year is supported by the Ontario created. 90 members, whose Arts Council. backgrounds and aesthetic Toronto Potters is exceptionally proud of its Biennial Exhibition history. As one This year the work was selected by Ju- interests reflect the of the highlights of membership, the rors Susan Collett and Gord Thompson, diversity of the city in exhibition takes place every two years. -

Single Tag Artist Info

Barbro Åberg, Sweden More Secrets, 2018 Clay with perlite and paper fibers, terra sigillata, stains, and oxides 18.5” x 23” x 5” Barbro Åberg received her degree in ceramics from The School of Arts and Crafts in Kolding, Denmark in 1988. She has had numerous solo exhibitions and participated in group exhibitions internationally and in Denmark. Her work is represented in museums and private collections. Barbro Åberg is a member of the International Academy of Ceramics (IAC). Lorri Acott, Untied States Missing Pieces, 2018 Paper clay 23” x 6” x 6” Lorri’s impressionistic figurative sculptures reside in private and public collections throughout the United States and abroad. A favorite of collectors and critics alike, her work provokes a powerful emotional response wherever it is placed. Lorri is the co- founder of DreamBigSculpture.com, a company specializing in the creation of large-scale artwork for both corporate and public collections worldwide. Jerry Bennett, United States Ozark, 2018 Porcelain paper clay and stainless-steel wire 40” x 22” x 18” Jerry Bennett received his MFA from Indiana University in 1975 and was a resident artist at the Philadelphia Clay Studio. He was an honored guest at the first International Paperclay Symposium and a leader of the Second International Paperclay Symposium in Kecskemet, Hungary. His work is in many galleries and museums worldwide. Vincent Burke, United States Flayed, 2017 Paper clay 14” x 16” x 22” Originally from Denver, Colorado, Vincent holds a BA in Art History from Carleton College and an MFA in Ceramics from Louisiana State University. He is currently an Associate Professor of Art at The University of Texas at El Paso. -

Clay Studio Vince Pitelka, 2016 Glossary of Ceramics Terminology

Appalachian Center for Craft - Clay Studio Vince Pitelka, 2016 Glossary of Ceramics Terminology NOTE: For identification and definitions of ceramic raw materials, see separate glossary of ceramics materials. ABSORPTION: The capacity of fired clay to absorb water. Measuring absorption serves as a gauge of vitrification. ACIDS: In clay and glaze chemistry, the glass-formers that combine with bases (fluxes) and neutrals (refractories or stabilizers). ADDITIVE: Adding clay to surface of work as forming/decorating method. See subtractive. AIR-FLOATED; AIR-FLOATING: Industrial method used in processing of raw clays, where powdered clay is floated in an airstream to settle out heavier particles. AIR-SET; AIR-SETTING: Castable refractory or mortar that develops hardness and strength before firing and must be kept damp during curing to develop maximum strength. AIR-SHUTTER: Adjustable opening on the rear of an atmospheric burner or on the blower intake of a power-burner, used to regulate entrainment of primary air. AGATEWARE: Wares featuring swirling marbleized colors resulting from surface slip effects or use of marbleized colored clays. ALKALINE: Basic, opposite of acidic - chemical nature of many fluxes. ALKALINE EARTHS: A category of highfire fluxes that includes calcium, magnesium, barium, and strontium. Encourage hard, durable surfaces, and matt surfaces in greater amounts. ALKALINE FLUXES: Major category of fluxes including boron, sodium, potassium, and lithium. ALUMINA: Aluminum oxide – the primary stabilizer/refractory in clay and glazes. ALUMINA WAX: Wax resist with alumina added, one teaspoon per pint. Used to prevent plucking and sticking during glaze firing, especially with porcelain bodies. ALUMINUM SILICATE: Broad category of materials composed primarily of alumina and silica. -

Winter/Spring 2019 | Vol 47 No 1 PRINTING and PAPER CLAY

Winter/Spring 2019 | Vol 47 No 1 PRINTING AND PAPER CLAY PRINTING studio potter 1 | Mission Centered in studio practice, Studio Potter promotes discus- sion of technology, criticism, aesthetics, and history within the ceramics community. We are a non-profit organization celebrating over forty years of commitment to publishing the Studio Potter journal. We , 2018. 15 x 8 in. welcome hearing from potters, artists, scholars, educators, and others with special interests in Blue Vein #8 Blue Vein writing and reporting on topics Potter Studio and events that matter in their | Porcelain paper clay, glaze. Photograph by Guy Nicol. glaze. paper clay, Porcelain Shiyuan Xu. personal and professional lives. 1 VOL 47 NO 1 PRINTING & PAPER CLAY In this Issue PRINTING Letter from Guest Editor The Architecture of Borderlands 04 | BRYAN CZIBESZ 22 | A CONVERSATION WITH RONALD RAEL A Perspective on Computers & Clay Ephemeral Materal 06 | BY RICHARD BURKETT 32 | BY STACY JO SCOTT Code & the Crafts What Do You Want to Be, Clay? | BY WENDY GERS WITH 10 39 | BY TOM LAUERMAN FRANÇOIS BRUMENT AND SONIA LAUGIER X > CTRL + P Potting in a Digital Age 43 | AN INTERVEW WITH UNFOLD 16 | BY JONATHON KEEP REMEMBERING When I am working in my studio, I think about the use a pot will be put to in someone's home ... through time, we ourselves change, and thus we change the emphasis of the pot. Barbro Aberg. More Secrets, 2018. 19x24x5 in. Clay with perlite and paper fibers, terra Ronald Rael. Cabin of sigillata, stains, oxides. Photo 3D-Printed Curiosities 66 by Lars Henrik Mardahl. -

Porcelain a Diverse Medium for Modern Times

Porcelain A Diverse Medium for Modern Times Antoinette Badenhorst traces the lineage of porcelain and its uses Ruth Duckworth. iscussions about the qualities and authenticity of porcelain Untitled. 2005. are often times raised by potters while at the same time Porcelain, 23 x 10 x 3.5 in. the general public has limited knowledge and informa- Archival Inventory # 877505 Photo by Guy Nicol. Dtion about handmade porcelain. The purists among us in the clay society believe that the term porcelain should not be borrowed in the use of alternative firing methods or by those that adjust the traditional porcelain clay com- position to meet some, but not all of the porcelain characteristics. Some go so far as to believe that only porcelain from ancient Eastern countries is true porcelain and that any other composed white clay bodies are considered white ware. Potters who have worked with porcelain and exhibited objects from high fire to pit fire believe that the term porcelain has moved beyond its traditional definition. There are those who believe that porcelain clay became as easy to get as any stoneware or earthenware clay body and that it does not deserve any elite tag to it. These discussions of what is considered porcelain keep coming back: Is ‘true porcelain’ a specific product with limited and traditional ingredients, firing methods, shapes and forms or is it open for experimentation? To understand and decide where one’s senti- ments lie requires a review of porcelain’s intriguing history, stretching from China to Europe. In 1500 BC, Chinese potters referred to porcelain as Tz’u’.