William Reece Smith, Jr. Distinguished Lecture in Legal Ethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2010 U.S

178451_Cover_B.qxd:178451_Cover_B 12/6/10 10:04 PM Page 1 Nonprofit Org. FALL 2010 U.S. Postage IN THIS ISSUE FALL 2010 FALL 421 Mondale Hall PAID New Environmental Courses • Q&A: Anderson & Rosenbaum • Super CLE Week • Don Marshall Tribute 229 19th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN Minneapolis, MN 55455 Permit No. 155 Perspectives E NVIRONMENTAL C APRIL 15—16, 2011 OURSES • Q&A: A PLEASE JOIN US AS WE CELEBRATE THE LAW SCHOOL AND ITS ALUMNI IN A WEEKEND OF ACTIVITIES FOR THE ENTIRE LAW SCHOOL COMMUNITY. NDERSON Friday, April 15: All-Alumni Cocktail Reception Saturday, April 16: Alumni Breakfast & CLE & R OSENBAUM SPECIAL REUNION EVENTS WILL BE HELD FOR THE CLASSES OF: 1961, 1971, 1976, 1981, 1986, 1991, 1996, 2001, and 2006 • CLE • D FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION, OR IF YOU ARE INTERESTED IN PARTICIPATING IN ON M THE PLANNING OF YOUR CLASS REUNION, PLEASE CONTACT EVAN P. JOHNSON, ARSHALL Alumni Relations & Annual Giving Program Manager T 612.625.6584 or [email protected] RIBUTE Spring Alumni Weekend is about returning to remember your years at the Law School and the friendships you built here. We encourage those of you with class reunions in 2011 to “participate in something great” by making an increased gift or pledge to the Law School this year. Where the Trials Are www.law.umn.edu WWW.COMMUNITY.LAW.UMN.EDU/SAW Criminal law is challenging but satisfying, say alumni from all sides of the courtroom. 178451_Cover_B.qxd:178451_Cover_B178451_Cover_B.qxd:178451_Cover_B 12/6/10 12/6/10 10:04 10:04 PM PagePM Page2 2 178451_Section A FrMatter.qxd:178451_Section A FrMatter 12/3/10 11:56 AM Page 1 Securing Our Future his fall we welcomed 260 first-year students, along with 36 LL.M. -

If It's Broke, Fix It: Restoring Federal Government Ethics and Rule Of

If it’s Broke, Fix it Restoring Federal Government Ethics and Rule of Law Edited by Norman Eisen The editor and authors of this report are deeply grateful to several indi- viduals who were indispensable in its research and production. Colby Galliher is a Project and Research Assistant in the Governance Studies program of the Brookings Institution. Maya Gros and Kate Tandberg both worked as Interns in the Governance Studies program at Brookings. All three of them conducted essential fact-checking and proofreading of the text, standardized the citations, and managed the report’s production by coordinating with the authors and editor. IF IT’S BROKE, FIX IT 1 Table of Contents Editor’s Note: A New Day Dawns ................................................................................. 3 By Norman Eisen Introduction ........................................................................................................ 7 President Trump’s Profiteering .................................................................................. 10 By Virginia Canter Conflicts of Interest ............................................................................................... 12 By Walter Shaub Mandatory Divestitures ...................................................................................... 12 Blind-Managed Accounts .................................................................................... 12 Notification of Divestitures .................................................................................. 13 Discretionary Trusts -

Ethics and Government Lawyering in the Age of Trump with Richard Painter

Yeshiva University, Cardozo School of Law LARC @ Cardozo Law Event Invitations 2018 Event Invitations 2-19-2018 Ethics and Government Lawyering in the Age of Trump With Richard Painter Jacob Burns Center for Ethics in the Practice of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://larc.cardozo.yu.edu/event-invitations-2018 Recommended Citation Jacob Burns Center for Ethics in the Practice of Law, "Ethics and Government Lawyering in the Age of Trump With Richard Painter" (2018). Event Invitations 2018. 6. https://larc.cardozo.yu.edu/event-invitations-2018/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Event Invitations at LARC @ Cardozo Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Event Invitations 2018 by an authorized administrator of LARC @ Cardozo Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Jacob Burns Center invites you to: Ethics and Government Lawyering in the Age of Trump with Richard Painter The Jacob Burns Center for Ethics in the Practice of Law invites you to the third event in its Speaker Series on Ethics and Government Lawyering in the Age of Trump. The series probes the ethical challenges confronting government lawyers in the Trump era and features prominent members of former Presidential Administrations and leading scholars of legal ethics. Richard W. Painter is the S. Walter Richey Professor of Corporate Law at the University of Minnesota Law School. From 2005 to 2007, he was the chief White House ethics lawyer in the Administration of President George W. Bush. His book, Getting the Government America Deserves: How Ethics Reform Can Make a Difference was published by Oxford University Press in January 2009. -

Letter of Complaint to the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Ethics

Letter of Complaint to the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Ethics Request for Investigation of Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC), Chairman of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, for Alleged Ethics Violations by Claire Finkelstein, Algernon Biddle Professor of Law and Professor of Philosophy, University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School, Richard Painter, S. Walter Richey Professor of Corporate Law, University of Minnesota Law School; and Walter Schaub, former Director, U.S. Office of Government Ethics November 18, 2020 The views expressed in this writing are the authors' own and do not necessarily represent those of any university or organization. Claire O. Finkelstein Algernon Biddle Professor of Law and Professor of Philosophy Faculty Director, Center for Ethics and the Rule of Law University of Pennsylvania Law School 3501 Sansom Street Philadelphia, PA 19104 Richard W. Painter S. Walter Richey Professor of Corporate Law University of Minnesota Law School 229 19th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55455 Walter M. Shaub, Jr. former Director, U.S. Office of Government Ethics November 18, 2020 Chairman James Lankford Vice Chairman Christopher Coons U.S. Senate Select Committee on Ethics 220 Hart Building United States Senate Washington, DC 20510 Via email to: [email protected] Re: Request for Investigation of Senator Lindsey Graham Dear Chairman Lankford and Vice Chairman Coons: We write to urge the Senate Select Committee on Ethics to investigate whether Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Lindsey Graham (R-SC) called Georgia’s Secretary of State, Brad Raffensperger, to discuss his ongoing count of votes for the office of president. We further urge the committee to investigate whether Senator Graham suggested that Secretary Raffensperger disenfranchise Georgia voters by not counting votes lawfully cast for the office of president. -

FALL 2016 PAID 421 Mondale Hall TWIN CITIES, MN 229 19Th Avenue South PERMIT NO

NONPROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE FALL 2016 FALL PAID 421 Mondale Hall TWIN CITIES, MN 229 19th Avenue South PERMIT NO. 90155 Minneapolis, MN 55455 PERSPECTIVES FALL 2016 The Magazine for the University of Minnesota Law School PERSPECTIVES THE MAGAZINE FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA LAW SCHOOL LAW THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA FOR THE MAGAZINE GARRY W. JENKINS: “Thank you for helping the Law School lead the way in legal education. It means so much to know that we have Lawyer. Scholar. the support of donors like you!” —Alex Bollman (’18) Leader. Dean. Justice Sonia Sotomayor Visits the Law School Minnesota Law On Tuesday, Sept. 27, hundreds of students, faculty, and staff celebrated the first Review Symposium: Gopher Gratitude Day at the University of Minnesota Law School. This event gave the entire First Amendment Law School community the opportunity to come together to say thank you to the many v. Inclusivity alumni, donors, and friends who generously provide their support. Theory at Work: Myron Orfield Faculty Profile: Richard W. Painter law.umn.edu 326812_COVER.indd 1 11/10/16 11:30 AM THANK YOU, PARTNERS AT WORK GROUP 1 (UP TO 9 ALUMNI) DEAN BOARD OF ADVISORS Perspectives is a general interest magazine published Garry W. Jenkins Jeanette M. Bazis (’92) in the fall and spring of the academic year for the Thank you to all volunteers, organizations, Gaskins Bennett Birrell Schupp 100% Sitso W. Bediako (’08) University of Minnesota Law School community of alumni, DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS Amy L. Bergquist (’07) friends, and supporters. Letters to the editor or any other and firms that participated in the ninth Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher 100% Cynthia Huff Karin J. -

(CERL) at Penn Law Files Amicus Brief in the US Supreme Court Case

The Center for Ethics and the Rule of Law (CERL) at Penn Law files amicus brief in the U.S. Supreme Court case Trump v. Vance supporting NY County’s issuance of subpoenas for Trump’s personal financial records The case is likely the most important executive power and immunity case to be decided since U.S. v. Nixon and Clinton v. Jones Contact: Eileen Kenney | CERL Director of Engagement [email protected] |215.629.6705 (Philadelphia – March 5, 2020) – Claire Finkelstein, Penn law professor and CERL director, and Richard Painter, counsel of record and University of Minnesota Law School professor, yesterday filed an amicus brief in the U.S. Supreme Court supporting New York County District Attorney’s issuance of subpoenas to President Trump’s accounting firms for Trump’s financial records as part of a state criminal investigation of the president’s businesses. In the brief, Finkelstein refuted the U.S. Solicitor General’s argument that the president has absolute immunity under Article II of the U.S. Constitution, which would bar state and county prosecutors from criminally investigating and prosecuting Trump and his businesses. “Such a claim of presidential immunity threatens to eliminate all accountability, not just for this president, but for all future presidents,” said Finkelstein. “If the Supreme Court adopts the Solicitor General’s interpretation, anyone occupying the office of the president would be beyond the reach of state and federal judicial processes.” District Attorney Cyrus Vance is conducting a criminal investigation of New York City-headquartered businesses beneficially owned by Trump. Vance subpoenaed Mazars and other accounting firms for financial documents, including tax returns, related to the businesses. -

Trading Controversy Dogs Health Secretary Nominee Tom Price

Spectrum | Autism Research News https://www.spectrumnews.org NEWS Trading controversy dogs health secretary nominee Tom Price BY MARISA TAYLOR, CHRISTINA JEWETT, KAISER HEALTH NEWS 9 FEBRUARY 2017 U.S. Health and Human Services (HHS) secretary nominee Tom Price showed little restraint in his personal stock trading during the three years that federal investigators were bearing down on a key House committee on which the Republican congressman served, a review of his financial disclosures shows. Price made dozens of health industry stock trades during a three-year investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) that focused on the Ways and Means Committee, according to financial disclosure records he filed with the House of Representatives. The investigation was considered the first test of a law passed to ban members of Congress and their staffs from trading stock based on insider information. Price was never a target of the federal investigation, which scrutinized a top Ways and Means staffer, and no charges were brought. But ethics experts say Price’s personal trading, even during the thick of federal pressure on his committee, shows he was unconcerned about financial investments that could create an appearance of impropriety. “He should have known better,” Richard Painter, former White House chief ethics attorney under President George W. Bush and professor of corporate law at the University of Minnesota Law School, said of Price’s conduct during the SEC inquiry. As Price awaits a Senate vote on his confirmation, Senate Democrats and a number of watchdog groups have asked the SEC to investigate whether Price engaged in insider trading with some of his trades in healthcare companies. -

Trump’S Business Interests

ResolvedDetails - Agency Information Management System Page 1 of 1 AIMS Agency Information Management System Announcement: If you create a duplicate interaction, please contact Gwen Cannon-Jenkins to have it deleted Resolved Interactions Details Reopen Interaction Resolution Details Title: Interaction Resolved:11/30/2016 34 press calls Resolution Category:Resolved Interaction #: 10260 Response: Like everyone else, we were excited this morning to read Status: Resolved the President-elect’s twitter feed indicating that he wants to be free of conflicts of interest. OGE applauds that goal, which is consistent with an opinion OGE issued in 1983. Customer Information Divestiture resolves conflicts of interest in a way that transferring control does not. We don’t know the details of Source: Press Position: their plan, but we are willing and eager to help them with it. The tweets that OGE posted today were responding only First Name: James Email: (b)(6) ' to the public statement that the President-elect made on Last Name: Lipton Phone: his Twitter feed about his plans regarding conflicts of Title: Reporter - NYT Other Notes: This contact is a stand-in interest. OGE’s tweets were not based on any information contact for the 34 separate news about the President-elect’s plans beyond what was shared organizations who contacted us and who on his Twitter feed. OGE is non-partisan and does not received our statement on the issue. endorse any individual. https://twitter.com/OfficeGovEthics Complexity( Amount Of Time Spent On Interaction:More than 8 Interaction Details hours Initiated: 11/30/2016 Individuals Credited:Leigh Francis, Seth Jaffe Call Origination: Phone Add To Agency Profile: No Assigned: Seth Jaffe Memorialize Content: No Watching: Do Not Destroy: No Questions We received inquires from 34 separate news organizations concerning tweets from OGE's twitter account addressing the President-elect's plans to avoid conflicts of interest. -

NORMAN L. EISEN the Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Ave NW Washington, DC 20036 (202) 238-3178 [email protected] [email protected]

1 AMBASSADOR (RET.) NORMAN L. EISEN The Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Ave NW Washington, DC 20036 (202) 238-3178 [email protected] [email protected] CURRICULUM VITAE PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE The Brookings Institution Senior Fellow, Governance Studies 1775 Massachusetts Ave NW, Washington, DC 20036 September 2014–Present (Visiting Fellow through 12/2016; Fellow through 6/2017) Author of A Case for the American People: The United States v. Donald J. Trump (Crown 2020); The Last Palace: Europe’s Turbulent Century in Five Lives and One Legendary House (Crown 2018); Democracy’s Defenders: U.S. Embassy Prague, the Fall of Communism in Czechoslovakia, and its Aftermath (Brookings Institution Press 2020); and numerous reports and other writings. Project chair and principal investigator of “Leveraging Transparency to Reduce Corruption,” a five-year global study examining transparency, accountability, and participation (TAP) mechanisms, along with their contextual factors, in the extractives industry. Convene and lead dialogues at Brookings with diplomatic, government, business, and nonprofit leaders from the United States and Europe. Speak before government bodies and other audiences on governance issues domestically and internationally, including regarding legislation, regulation, and policy formation. Regularly author op-eds in such outlets as the New York Times and the Washington Post and appear on television and radio to present transatlantic relations and governance issues to the general public. Committee on the Judiciary of the U.S. House of Representatives Special Counsel 2138 Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 February 2019–February 2020 Counsel for oversight and policy issues within the Committee’s jurisdiction, including the investigation, impeachment and trial of President Donald Trump. -

Litigators of the Week: One for the History Books

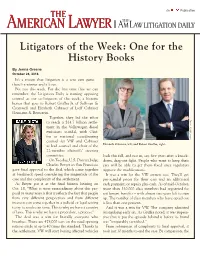

Litigators of the Week: One for the History Books By Jenna Greene October 28, 2016 It’s a truism that litigation is a zero sum game— there’s a winner and a loser. But not this week. For the first time that we can remember, the Litigation Daily is naming opposing counsel as our co-litigators of the week, a historic honor that goes to Robert Giuffra Jr. of Sullivan & Cromwell and Elizabeth Cabraser of Lieff Cabraser Heimann & Bernstein. Together, they led the effort Photos: ALM/Courtesy to reach a $14.7 billion settle- ment in the Volkswagen diesel emissions scandal, with Giuf- fra as national coordinating counsel for VW and Cabraser as lead counsel and chair of the Elizabeth Cabraser, left, and Robert Giuffra, right. 22-member plaintiffs’ steering committee. back this fall, and not in, say, five years after a knock- On Tuesday, U.S. District Judge down, drag-out fight. People who want to keep their Charles Breyer in San Francisco cars will be able to get them fixed once regulators gave final approval to the deal, which came together approve the modifications. at breakneck speed considering the magnitude of the It was a win for the VW owners too. They’ll get case and the complexity of the settlement. pre-scandal prices for their cars and an additional As Breyer put it at the final fairness hearing on cash payment, or repairs plus cash. As of mid-October, Oct. 18, “What is most extraordinary about this pro- more than 330,000 class members had registered for posal in many ways is that it reflects the fact that people settlement benefits – with almost two years left to sign from very different perspectives and from different up. -

Ad Hoc Group of the Center for Ethics and the Rule of Law (CERL) and Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW) Issues Report Sharply Critical of U.S

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Meredith Rovine [email protected] Ad Hoc Group of the Center for Ethics and the Rule of Law (CERL) and Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW) Issues Report Sharply Critical of U.S. Attorney General William Barr and DOJ Activities A nonpartisan legal and ethics group calls for an impeachment inquiry after its in-depth study; group concludes Barr compromised U.S. interests, jeopardized national security October 12, 2020 (Philadelphia) —The Center for Ethics and the Rule of Law (CERL) Ad Hoc Working Group, in partnership with Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW), released today its “Report on the Department of Justice and the Rule of Law under the Tenure of Attorney General William Barr,” a 267-page comprehensive report based on an extensive study of Barr’s and DOJ practices and policies since Barr’s confirmation in 2019. “For the United States to remain a ‘government of laws, and not of men,’ it is essential that our nation’s highest law enforcement office maintains independence from partisan politics and the executive branch,” said Ad Hoc Working Group Co-Chair Claire Finkelstein, Penn Law professor and Faculty Director of CERL. “After months of study, our group has concluded that Mr. Barr has compromised U.S. interests and jeopardized national security,” she stated. “He has an authoritarian worldview that limits his adherence to the rule of law.” CERL and CREW undertook the project to examine ethics and rule of law concerns in a number of areas ranging from the Mueller Report rollout to deployment of federal troops against protestors. -

Postal Update Hearing Committee On

POSTAL UPDATE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 14, 2020 Serial No. 116–117 Printed for the use of the Committee on Oversight and Reform ( Available on: govinfo.gov, oversight.house.gov or docs.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 41–956 PDF WASHINGTON : 2020 COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND REFORM CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York, Chairwoman ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JAMES COMER, Kentucky, Ranking Minority Columbia Member WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri JIM JORDAN, Ohio STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts PAUL A. GOSAR, Arizona JIM COOPER, Tennessee VIRGINIA FOXX, North Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia THOMAS MASSIE, Kentucky RAJA KRISHNAMOORTHI, Illinois JODY B. HICE, Georgia JAMIE RASKIN, Maryland GLENN GROTHMAN, Wisconsin HARLEY ROUDA, California GARY PALMER, Alabama RO KHANNA, California MICHAEL CLOUD, Texas KWEISI MFUME, Maryland BOB GIBBS, Ohio DEBBIE WASSERMAN SCHULTZ, Florida CLAY HIGGINS, Louisiana JOHN P. SARBANES, Maryland RALPH NORMAN, South Carolina PETER WELCH, Vermont CHIP ROY, Texas JACKIE SPEIER, California CAROL D. MILLER, West Virginia ROBIN L. KELLY, Illinois MARK E. GREEN, Tennessee MARK DESAULNIER, California KELLY ARMSTRONG, North Dakota BRENDA L. LAWRENCE, Michigan W. GREGORY STEUBE, Florida STACEY E. PLASKETT, Virgin Islands FRED KELLER, Pennsylvania JIMMY GOMEZ, California ALEXANDRIA OCASIO-CORTEZ, New York AYANNA PRESSLEY, Massachusetts RASHIDA TLAIB, Michigan KATIE PORTER, California DAVID RAPALLO, Staff Director WENDY GINSBERG, Subcommittee Staff Director AMY STRATTON, Clerk CONTACT NUMBER: 202-225-5051 CHRISTOPHER HIXON, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia, Chairman ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JODY B.