Hydrology and Sustainable Indigenous Populations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shorezone Coastal Habitat Mapping Data Summary Report Northwest

CORI Project: 12-27 September 2013 ShoreZone Coastal Habitat Mapping Data Summary Report Northwest Alaska Survey Area Prepared for: NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service, Alaska Region Prepared by: COASTAL & OCEAN RESOURCES ARCHIPELAGO MARINE RESEARCH LTD 759A Vanalman Ave., Victoria BC V8Z 3B8 Canada 525 Head Street, Victoria BC V9A 5S1 Canada (250) 658-4050 (250) 383-4535 www.coastalandoceans.com www.archipelago.ca September 2013 Northwest Alaska Summary (NOAA) 2 SUMMARY ShoreZone is a coastal habitat mapping and classification system in which georeferenced aerial imagery is collected specifically for the interpretation and integration of geological and biological features of the intertidal zone and nearshore environment. The mapping methodology is summarized in Harney et al (2008). This data summary report provides information on geomorphic and biological features of 4,694 km of shoreline mapped for the 2012 survey of Northwest Alaska. The habitat inventory is comprised of 3,469 along-shore segments (units), averaging 1,353 m in length (note that the AK Coast 1:63,360 digital shoreline shows this mapping area encompassing 3,095 km, but mapping data based on better digital shorelines represent the same area with 4,694 km stretching along the coast). Organic/estuary shorelines (such as estuaries) are mapped along 744.4 km (15.9%) of the study area. Bedrock shorelines (Shore Types 1-5) are extremely limited along the shoreline with only 0.2% mapped. Close to half of the shoreline is classified as Tundra (44.3%) with low, vegetated peat the most commonly occurring tundra shore type. Approximately a third (34.1%) of the mapped coastal environment is characterized as sediment-dominated shorelines (Shore Types 21-30). -

Oregon Shorezone Coastal Habitat Mapping Protocol, 2013

CORI Project: 12-18 30 June 2013 ShoreZone Coastal Habitat Mapping Protocol for Oregon (v. 3) 2013 prepared for Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Newport, Oregon prepared by: John R. Harper Coastal & Ocean Resources Mary Morris Archipelago Marine Research Ltd. Sean Daley Coastal & Ocean Resources COASTAL & OCEAN RESOURCES ARCHIPELAGO MARINE RESEARCH LTD. 759A Vanalman Ave 525 Head Street Victoria, BC V8Z 3B8 Canada Victoria BC V9A 5S1 Canada 250 658-4050 (250) 383-4535 www.coastalandoceans.com www.archipelago.ca SUMMARY The coastal zone is a crucial interface for terrestrial and marine organisms, human activities, and dynamic processes. ShoreZone is a coastal habitat mapping and classification system that specializes in (a) the collection of spatially-referenced aerial imagery of the intertidal zone and and classification of visible features in that imagery. ShoreZone provides an integrated, searchable inventory of geomorphic and biological features which can be used as a tool for science, education, management, and environmental hazard mitigation. This report provides documentation of the ShoreZone Coastal Habitat Mapping Program in the State of Oregon. The protocol is meant to: Provide an overview of the ShoreZone program and its procedures. Specify standards for image collection and intertidal/nearshore habitat mapping so that users will have an understanding of the methodology and to ensure consistency in its use. Provide illustrated examples of mapped features from Oregon. The ShoreZone system utilizes spatially referenced, oblique aerial video and digital still imagery of the coastal zone collected during the lowest daylight tides of the year. Image interpretation and mapping is accomplished by a team of physical and biological scientists. -

Coastal Habitat Mapping Program

Coastal Habitat Mapping Program Oregon Data Summary Report June 2014 Prepared for: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife CORI Project: 12-18 June 2014 ShoreZone Coastal Habitat Mapping Data Summary Report Oregon Survey Area Prepared for: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Prepared by: COASTAL & OCEAN RESOURCES ARCHIPELAGO MARINE RESEARCH LTD 759A Vanalman Ave., Victoria BC V8Z 3B8 Canada 525 Head Street, Victoria BC V9A 5S1 Canada (250) 658-4050 (250) 383-4535 www.coastalandoceans.com www.archipelago.ca June 2014 Oregon Summary Report (ODFW) 2 SUMMARY ShoreZone is a coastal habitat mapping and classification system in which georeferenced aerial imagery is collected specifically for the interpretation and integration of geological and biological features of the intertidal zone and nearshore environment. The mapping methodology is summarized in Harper et al (2013). This data summary report provides information on geomorphic and biological features of 2,633 km of shoreline mapped for the 2011 coastal survey of Oregon. The habitat inventory is comprised of 3,223 along-shore segments (units), averaging 817 m in length (based on the CUSP_OR shoreline)1. Organic shore types, usually dominated by fine sediment and marshes, are mapped along 1,202.1 km (45.7%) of the study area. Bedrock shore types (Shore Types 1-5) are uncommon with only 7.8% mapped. A third (33.7%) of the mapped coastal environment is characterized as Sediment-dominated shore types (Shore Types 21- 30). Of these, wide sand flats (Shore Type 28) are the most common, mapped along 495.2 km of shoreline (18.8% of the total study area). -

Shorezone Coastal Imaging and Habitat Mapping Protocol December 2017

ShoreZone Coastal Imaging & Habitat Mapping Protocol December 2017 On the cover: Photos on Previous Page: Helm Point, Coronation Island, Alaska Bangookbit Dunes, Nunivak Island, Alaska Coos Bay, Oregon Prince Rupert, British Columbia ShoreZone Coastal Imaging and Habitat Mapping Protocol December 2017 Prepared By Sarah Cook, Sean Daley, Kalen Morrow and Sheri Ward Coastal and Ocean Resources, Victoria, B.C., Canada Prepared For NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service Alaska Region, Habitat Conservation Division, Juneau, AK This page left blank ii Summary ShoreZone is an aerial imaging, coastal habitat classification and mapping system used to inventory alongshore and across-shore geomorphological and biological attributes of the shoreline. The georeferenced, oblique, low altitude aerial imagery is acquired during the lowest tides of the year and then used to classify habitat attributes into a searchable database. This data is used for coastal planning, identification of vulnerable resources, oil spill response planning, habitat modeling, recreational planning and scientific research. The conceptual framework for the ShoreZone habitat mapping and classification system was developed and tested on shorelines near Victoria, British Columbia in the summer of 1979. The standardized protocols for both the imagery collection and habitat classification, which were developed shortly thereafter, have been updated as throughout the years. Improvements in technology has allowed for the collection of more detailed data from the high resolution digital imagery, although the basic attributes have remained consistent for ShoreZone mapping, which now covers over 120,000 km of the west coast of North America and into the Arctic. The imagery and habitat data, including previous protocols and summery reports for Alaska, Oregon and Washington State, are accessible from either the NOAA ShoreZone or ShoreZone.org websites. -

Coastal Habitat Mapping Program

Coastal Habitat Mapping Program Southeast Alaska Data Summary Report ShoreZone October 2011 Prepared for: The Nature Conservancy On the Cover: South Coronation Island Sawyer Glacier, Tracy Arm North Zarembo Island Juneau, AK CORI Project: 10-17 Oct 2011 ShoreZone Coastal Habitat Mapping Data Summary Report 2004-2010 Survey Area, Southeast Alaska Prepared for: NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service, Alaska Region The Nature Conservancy Prepared by: COASTAL & OCEAN RESOURCES INC ARCHIPELAGO MARINE RESEARCH LTD 759A Vanalman Ave., Victoria BC V8Z 3B8 Canada 525 Head Street, Victoria BC V9A 5S1 Canada (250) 658-4050 (250) 383-4535 www.coastalandoceans.com www.archipelago.ca October 2011 SE Alaska Summary (TNC) 2 SUMMARY ShoreZone is a coastal habitat mapping and classification system in which georeferenced aerial imagery is collected specifically for the interpretation and integration of geological and biological features of the intertidal zone and nearshore environment. The mapping methodology is summarized in Harney et al (2008). This interim data summary report provides information on geomorphic and biological features of 28,595 km of shoreline mapped in 2004-2010 surveys of Southeast Alaska. There is approximately 1,100 km of unmapped shoreline in Glacier Bay. The habitat inventory is comprised of 88,704 along-shore segments (units), averaging 322 m in length. Organic shorelines (such as estuaries) are mapped along 3,388 km (12%) of the study area. Bedrock shorelines (BC Classes 1-5) comprise 4,947 km (17%) of mapped shorelines. Of these, steep rock cliffs are the most common mapped along 3,682 km (13%) of the shoreline. A little less than half of the mapped coastal environment is characterized as combinations of rock and sediment shorelines (BC Classes 6-20): 11,747 km (41%). -

The Washington State Shorezone Inventory User's Manual

The Washington State ShoreZone Inventory User’s Manual By Helen D. Berry, John R. Harper, Tom F. Mumford, Jr., Betty E. Bookheim, Amy T. Sewell, Linda J. Tamayo Nearshore Habitat Program Washington State Department of Natural Resources PO BOX 47014 Olympia, WA 98504-7014 360.902.1600 Washington State ShoreZone Inventory User’s Manual Page 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Washington State ShoreZone Inventory Between 1994 and 2000, the Nearshore Habitat Program inventoried Washington’s saltwater shorelines statewide. The resulting ShoreZone Inventory describes the physical and biological characteristics of intertidal and shallow subtidal areas. It can be used to better understand and manage Washington’s coastal ecosystem. This manual is designed for users of Washington ShoreZone Inventory data. The manual explains how the data set is organized, how it was developed, and how it can be used. The Inventory Data The ShoreZone Inventory is available on CD-ROM for Windows and UNIX based systems. There is no fee for the data, but all users must comply with the terms of the license agreement. The ShoreZone Inventory data consists of spatial data, tabular data, and documentation: · Documentation: The User’s Manual and Data Dictionary are available in .html format for online viewing and .pdf format for printing. These files are located in the szdoc directory on the CD-ROM. (userman.pdf, datadic.pdf) · Easy-to-use themes: A series of easy-to-use themes cover the most-requested information, such as eelgrass distribution, percentage of shoreline modification, and shoreline type. These ArcView shape files are located in the szthemes directory on the CD-ROM. -

Anticipated Effects of Sea Level Rise in Puget Sound on Two Beach-Spawning Fishes

Kirk L. Krueger and others 171 Anticipated Effects of Sea Level Rise in Puget Sound on Two Beach-Spawning Fishes Kirk L. Krueger1, Kenneth B. Pierce, Jr.1, Timothy Quinn1, and Daniel E. Penttila2 Introduction beaches might contract, which would reduce the extent of intertidal habitat and thus the amount of suitable spawning habitat. Where the upward extent of beach migration is The shoreline of Puget Sound provides habitat for many limited by shoreline armoring (Griggs and others, 1994; species, including surf smelt (Hypomesus pretiosus) and Griggs, 2005), loss of spawning habitat might be exacerbated Pacific sand lance Ammodytes( hexapterus); two fishes that (Thom and others, 1994). However, the question of whether spawn in the intertidal zone. Surf smelt and Pacific sand lance sea level rise will result in a loss of surf smelt and sand (hereinafter sand lance) are key parts of the Puget Sound food lance spawning habitat on armored shorelines has not been web (Simenstad and others, 1979), providing food for many addressed quantitatively. Our goals were (1) to describe the sea birds, marine mammals and fishes, including economically geographic and temporal distribution of surf smelt and sand and culturally important Pacific salmon Oncorhynchus( spp.). lance spawning in Puget Sound, including discontinuities in By integrating climate change predictions and their expected occurrence and egg abundance; (2) to describe associations effects on intertidal geological processes and subsequent between beach elevation and egg abundance; and (3) to ecological processes, we hope to inform policies to protect determine the potential for spawning habitat contraction and surf smelt and sand lance spawning habitat while addressing egg loss as a result of sea level rise on armored beaches. -

2016 Shorezone User Manual

2016 ShoreZone User Manual 2016 ShoreZone User Manual G. C. Schoch Coastal and Ocean Resources 759A Vanalman Ave. Victoria, British Columbia V8Z 3B8 Canada prepared for National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Alaska Region, Habitat Conservation Division P.O. Box 21668 Juneau, AK 99802 October 2016 2016 ShoreZone User Manual This page is intentionally blank. Suggested citation: Schoch, G.C., 2016. 2016 ShoreZone User Manual. Coastal and Ocean Resources, Victoria, BC. 170 p. 2016 ShoreZone User Manual Summary Evidence suggests that biological patterns of nearshore plants and animal are functionally linked to oceanic processes and physical characteristics of the shoreline. Mapping shoreline habitats can therefore provide important information for distribution studies of coastal biodiversity. But most mapping methods are too coarse-scaled to detect subtle environmental differences that may significantly alter biological structure. ShoreZone is an aerial imaging, coastal habitat classification, and mapping system used to inventory alongshore and across- shore geomorphological and biological attributes of the coast. Habitat attributes are interpreted from oblique low altitude aerial imagery acquired during the lowest tides of the year, then classified and entered into a searchable database. The data are used for coastal planning, identification of vulnerable resources, oil spill response planning, habitat modeling, recreational planning, and scientific research. The conceptual framework of the ShoreZone habitat mapping and classification system was developed and tested on shorelines near Victoria, British Columbia in the summer of 1979. Today the ShoreZone system utilizes spatially referenced, high definition oblique aerial video and digital still imagery. The images are processed to create digital elevations models of the shoreline. -

Shorezone Imaging and Mapping Along the Alaska Peninsula

OCS Study BOEM 2018-037 ShoreZone Imaging and Mapping along the Alaska Peninsula US Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Alaska OCS Region This page intentionally left blank. OCS Study BOEM 2018-037 ShoreZone Imaging and Mapping along the Alaska Peninsula August 2018 Authors: Sarah Cook, Sean Daley, Sue Saupe, Mandy Lindeberg, Mary Morris, Kalen Morrow, Rachel Myers and Ashley Park Prepared under BOEM Award No. M15PC00008 By Coastal and Ocean Resources 759A Vanalman Ave. Victoria, BC, Canada V8Z 3B8 US Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Alaska OCS Region This page intentionally left blank. DISCLAIMER Study concept, oversight, and funding were provided by the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), Environmental Studies Program, Washington, DC, under Contract Number M15PC00008. This report has been technically reviewed by BOEM, and it has been approved for publication. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the US Government, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. REPORT AVAILABILITY To download a PDF file of this report, go to the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Data and Information Systems webpage (http://www.boem.gov/Environmental- Studies-EnvData/), click on the link for the Environmental Studies Program Information System (ESPIS), and search on 2018-037. The report is also available at the National Technical Reports Library at https://ntrl.ntis.gov/NTRL/. CITATION Cook S, Daley S, Saupe S., Lindeberg M., Morris M., Morrow K., Myers R., Park A. -

Shorezone Fact Sheet

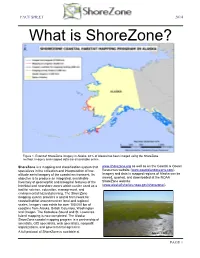

--- I ...._ FACT SHEET ~ShoreZone 2014 What is ShoreZone? N A SHOREZONE COASTAL HABITAT MAPPING PROGRAM IN ALASKA -- Imaged and mapped (61 ,698 km) -- Mapping in progress (5 ,692 km) -- Imaged; available for mapping funding (855 km) -- Imaging survey funded (1 ,890 km) Needs imagery (- 9,300 km) State of Alaska ALASKA \,. Map Date: September 2014 0 250 500 1,000 ----===:::::i------•Kilo meters Map produced by Coastal and Ocean Resources Figure 1. Extent of ShoreZone imagery in Alaska. 85% of Alaska has been imaged using the ShoreZone method. Imagery and mapped data are all available online. ShoreZone is a mapping and classification system that www.shorezone.org as well as on the Coastal & Ocean specializes in the collection and interpretation of low- Resources website (www.coastalandoceans.com). altitude aerial imagery of the coastal environment. Its Imagery and data in mapped regions of Alaska can be objective is to produce an integrated, searchable viewed, queried, and downloaded at the NOAA inventory of geomorphic and biological features of the ShoreZone website: intertidal and nearshore zones which can be used as a (www.alaskafisheries.noaa.gov/shorezone/). tool for science, education, management, and environmental hazard planning. The ShoreZone mapping system provides a spatial framework for coastal habitat assessment on local and regional scales. Imagery now exists for over 100,000 km of coastline from Alaska, British Columbia, Washington and Oregon. The Kotzebue Sound and St. Lawrence Island mapping is now completed. The Alaska ShoreZone coastal mapping program is a partnership of scientists, GIS specialists, web specialists, nonprofit organizations, and governmental agencies. A full protocol of ShoreZone is available at Sarah Cook PAGE 1 FACT SHEET 2014 THE METHOD Oblique low-altitude aerial video and digital still imagery of the shoreline is collected during summer low tides (zero-meter tide level or lower), usually from a helicopter flying at <100 m altitude. -

Download the Shorezone Fact Sheet

Where is ? Tigvariak Island, AK Jacksmith Bay, AK Sukkwan Strait, AK Ukolnoi Island, AK Galiano Island, BC Fly The Coast @ www.shorezone.org Cape Lookout, OR For more information go to www.coastalandoceans.com What is ? ShoreZone is an imaging and habitat mapping system that specializes in the collection and interpretation of low-altitude aerial imagery of the coastal environment. ShoreZone Imaging Oblique low-altitude aerial video and digital still imagery of the shoreline is collected during summer low tides (zero-meter tide level or lower), usually from a helicopter flying at 100 m altitude. Video and still images are geo-referenced using onboard GPS. ShoreZone Mapping The imagery is used to divide the shoreline into units with similar geomorphic characteristics and physical attributes (such as exposure, sediment type and size) are described. Biological attributes are then classified for each unit. The main biological attributes are called biobands, which are biotic communities recognizable due to characteristic colour, texture, exposure and tidal height. Examples of biobands are salt marsh (see example distribution map), canopy kelps and eelgrass. Units are digitized as shoreline segments in ArcGIS software, and then integrated with the coastal attribute data in a searchable relational geodatabase. The objective of ShoreZone is to produce an integrated, searchable inventory of physical and biological features of the intertidal and nearshore zones which can be used as a tool for science, education, management, and environmental hazard planning. The ShoreZone mapping system provides a spatial framework for coastal habitat assessment on local and regional scales. Imagery now exists for over 115,000 km of coastline from Alaska, British Columbia, Washington and Oregon (see over for map of extent). -

Shorezone in Alaska, a Tool with Many Applications

ShoreZone in Alaska, A Tool with Many Applications National Marine Fisheries Service Alaska Cindy Hartmann Moore, NMFS AKR Steve Lewis, NMFS, AKR Mandy Lindeberg, NMFS, AFSC, ABL Dr. John Harper, CORI ShoreZone is a coastal habitat mapping system that organizes physical and biological attributes of the coast into an integrated, searchable inventory. It is a tool for science, education, management and environmental hazard planning. Selawik Lake, Kotzebue Sound What is ShoreZone? Standardized Coastal Habitat Mapping System ShoreZone images and characterizes biophysical attributes in both along- shore and across-shore components in a spatially explicit environment. wave exposure geomorphology sediment texture intertidal/subtidal biota supratidal biota man-made features Alaska ShoreZone Program: A collaborative effort of many organizations. Initiated in Alaska in 2001. Acquiring Coastal Imagery (~ 86% imaged) Habitat Mapping Online Products (continual updates) & outreach Are we ShoreZone Progress in Alaska done yet? ShoreZone Protocol Imagery collection and mapping Guidelines for users Codes and definitions Diagrams Photographic examples Available on-line Acquiring Coastal Imagery Video and still imagery is acquired: Aerial imagery Low altitude Oblique Geo-referenced Collected during low tide window ShoreZone Mapping Process Use a systematic mapping system to convert imagery to searchable mapping data Mapper interpreting the imagery and coding it into the database ShoreZone Protocols - Shore Types Biophysical Mapping Physical