Phenomenal Intentionality and the Problem of Cognitive Contact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Through the Iris TH Wasteland SC Because the Night MM PS SC

10 Years 18 Days Through The Iris TH Saving Abel CB Wasteland SC 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10,000 Maniacs 1,2,3 Redlight SC Because The Night MM PS Simon Says DK SF SC 1975 Candy Everybody Wants DK Chocolate SF Like The Weather MM City MR More Than This MM PH Robbers SF SC 1975, The These Are The Days PI Chocolate MR Trouble Me SC 2 Chainz And Drake 100 Proof Aged In Soul No Lie (Clean) SB Somebody's Been Sleeping SC 2 Evisa 10CC Oh La La La SF Don't Turn Me Away G0 2 Live Crew Dreadlock Holiday KD SF ZM Do Wah Diddy SC Feel The Love G0 Me So Horny SC Food For Thought G0 We Want Some Pussy SC Good Morning Judge G0 2 Pac And Eminem I'm Mandy SF One Day At A Time PH I'm Not In Love DK EK 2 Pac And Eric Will MM SC Do For Love MM SF 2 Play, Thomas Jules And Jucxi D Life Is A Minestrone G0 Careless Whisper MR One Two Five G0 2 Unlimited People In Love G0 No Limits SF Rubber Bullets SF 20 Fingers Silly Love G0 Short Dick Man SC TU Things We Do For Love SC 21St Century Girls Things We Do For Love, The SF ZM 21St Century Girls SF Woman In Love G0 2Pac 112 California Love MM SF Come See Me SC California Love (Original Version) SC Cupid DI Changes SC Dance With Me CB SC Dear Mama DK SF It's Over Now DI SC How Do You Want It MM Only You SC I Get Around AX Peaches And Cream PH SC So Many Tears SB SG Thugz Mansion PH SC Right Here For You PH Until The End Of Time SC U Already Know SC Until The End Of Time (Radio Version) SC 112 And Ludacris 2PAC And Notorious B.I.G. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

EXACERBYTE Play List. Chapter 1

EXACERBYTE Play List. Chapter 1: Every Intention – Kevin Costner and Modern West Chapter 2: Joey – Bon Jovi Chapter 3: Another One Bites the Dust -Queen Chapter 4: Goin’ Away Baby – Eric Clapton Chapter 5: One Step Closer – Bon Jovi Chapter 6: We Got It Going On – Bon Jovi Chapter 7: Pretty Maids All In a Row – The Eagles Chapter 8: Story of My Life – Bon Jovi Chapter 9: What Happened To You – Lorenza Ponce Chapter 10: Lie To Me – Bon Jovi Chapter 11: Smells like Teen Spirit - Nirvana Chapter 12: Gimme the Prize - Queen Chapter 13: She’s a Mystery – Bon Jovi Chapter 14: Remedy – Lorenza Ponce Chapter 15: Now I’m Here - Queen Chapter 16: Bitter Wine – Bon Jovi Chapter 17: Wasted Time – The Eagles Chapter 18: Wish I Were You – Patty Smyth Chapter 19: Watch Out For Lucy. – Eric Clapton Chapter 20: Summertime – Bon Jovi Chapter 21: Wild Horses – The Rolling Stones Chapter 22: I Can’t Tell You Why – The Eagles Chapter 23: Unbreakable – Bon Jovi Chapter 24: Get Over It – The Eagles Chapter 25: Damned – Bon Jovi Chapter 26: Motherless Child – Eric Clapton Chapter 27: Bounce – Bon Jovi Chapter 28: Learn To Be Still – The Eagles Chapter 29: Beast Of Burden – The Rolling Stones Chapter 30: Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby? – The Rolling Stones Chapter 31: Any Other Day – Bon Jovi Chapter 32: Superman Tonight – Bon Jovi Chapter 33: Welcome to Where Ever You Are – Bon Jovi Chapter 34: Don’t Lose Your Head - Queen Chapter 35: Last Cigarette –Bon Jovi Chapter 36: Last Man Standing – Bon Jovi Chapter 37: We Weren’t Born to Follow – Bon Jovi Chapter 38: I Won’t Lose Faith – Lorenza Ponce Chapter 39: Stick to Your Guns – Bon Jovi Chapter 40: Live Before You Die – Bon Jovi Chapter 41: Let Me Be the One – Kevin Costner and Modern West Chapter 42: Mister Big Time – Jon Bon Jovi . -

Magazine Template

Saint Joseph’s University, Summer 2010 Achieving a First: SJU’s Personal Connections to Professor and Students Doneene Damon ‘89 Rebuilding Haiti Feed the Hungry FROM THE PRESIDENT A little more than five years ago, Saint Joseph’s University embarked on Plan 2010: The Path to Preeminence, an ambitious strategic plan that would enable us to be recognized as the Northeast’s preeminent Catholic comprehensive university. Now, with so many of Plan 2010’s initiatives accomplished, we look forward to the coming decade from a position of academic and financial strength. Our academic position has been affirmed by the tremendous achievements of our talented faculty and students. U.S. News & World Report recently ranked the Erivan K. Haub School of Business Executive MBA program 20th in the nation. Additionally, over the past two years, four graduating seniors in the College of Arts and Sciences were awarded Fulbright English Teaching Assistantships, among other prestigious scholarships. There is also wonderful news about graduates enrolled in the Jesuit Volunteer Corps (JVC). Saint Joseph’s tied with Gonzaga University for having the highest number of alumni participants in the JVC. I am immensely proud that 16 alumni have committed to one year of living and working for others. Our successes do not mean that we will rest on our laurels, however. Saint Joseph’s is blessed with a robust planning culture, and after more than a year of intensive data gathering and planning, a framework for Plan 2020: Gateway to the Future has crystallized. The bold steps we take as we continue to expand our goals will focus on Plan 2020’s five initiatives: academic distinction and a transformative student experience; mission and diversity; global and community engagement; alumni involvement; and financial health. -

Artist Song Album Blue Collar Down to the Line Four Wheel Drive

Artist Song Album (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Blue Collar Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Down To The Line Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Four Wheel Drive Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Free Wheelin' Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Gimme Your Money Please Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Hey You Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Let It Ride Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Lookin' Out For #1 Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Roll On Down The Highway Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Take It Like A Man Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Hits of 1974 (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothin' Yet Hits of 1974 (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. Blue Sky Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Rockaria Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Showdown Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Strange Magic Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Sweet Talkin' Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Telephone Line Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Turn To Stone Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. -

Superman Tonight.Ptb

SUPERMAN TONIGHT As recorded by Bon Jovi (From the 2009 Album THE CIRCLE) Transcribed by Slowhand Words and Music by Jon Bon Jovi, Richie Sambora & Billy Falcon A Intro = 132 N.C.P 1 g V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V I 4 Gtr IV (Clean El. Gtr. w/ delay & T 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 A B 5 g V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V I T 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 A 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 B B 1st Verse N.C. 9 g V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V I T 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 A 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 B 13 g V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V I T 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 A 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 B Generated using the Power Tab Editor by Brad Larsen. -

Bon Jovi Crush Download Album Crush

bon jovi crush download album Crush. Purchase and download this album in a wide variety of formats depending on your needs. Buy the album Starting at £12.49. Even if it was classified as pop-metal, Bon Jovi never really was much of a metal band, relying on big, catchy melodies and not guitar riffs to make their songs memorable. That's why, in 2000, they're able to make an album like Crush, which strays far enough into pop/rock to actually stand a chance of getting airplay (which it did, with the hit lead single "It's My Life"). The guitar crunch on the uptempo numbers keeps Bon Jovi from becoming a full-fledged pop/rock band, but in addition to the typical hard rockers, there are nods to heartland rock, Bryan Adams-style adult contemporary balladry ("Thank You for Loving Me"), the Beatles (the surprisingly effective "Say It Isn't So"), and even British glam à la T. Rex or David Bowie ("Captain Crash and the Beauty Queen From Mars"). Occasionally, it sounds like the band is attempting to cover as many bases as possible for multi-format appeal, but for the most part, the variety -- coupled with the consistently polished songcraft -- makes for a surprisingly listenable album. The production is a little more electronic-tinged, but not obtrusively high-tech, so the band doesn't come off as desperate to sound contemporary. Aside from a couple of missteps (the soppy, aforementioned "Thank You for Loving Me" and the mawkish posturing of "Save the World"), Crush is a solidly crafted mainstream rock record that's much better than most might expect. -

Flashbyte-Playlist

Flashbyte: play list Chapter one: Gotta get away – Kevin Costner and Modern west Chapter two: Real Men – Bon Jovi Chapter three: Bank Robber -The Clash Chapter four: Return to Sender – Elvis Chapter five: If I Could Turn Back Time – Cher Chapter six: Blood on Blood – Bon Jovi Chapter seven: We Rule the Night – Bon Jovi Chapter eight: Pop Rocks and Coke – Greenday Chapter nine: Hello, I love you – The Doors Chapter ten: It’s Now or Never – Elvis Chapter eleven: All these things that I’ve done – The Killers Chapter twelve: Living in Sin – Bon Jovi Chapter thirteen: Turn it On – Kevin Costner and Modern West Chapter fourteen: Superman Tonight – Bon Jovi Chapter fifteen: No Apologies – Bon Jovi Chapter sixteen: I Gotta Woman – Elvis Chapter seventeen: Live before you die – Bon Jovi Chapter eighteen: Living on a Prayer – Bon Jovi Chapter nineteen: Saturday Night – Kevin Costner and Modern West Chapter twenty: Runaway – Bon Jovi Chapter twenty-one: Thorn in my Side – Bon Jovi Chapter twenty-two: Stairway to Heaven – Led Zeppelin Chapter twenty-three: We All Sleep Alone – Cher Chapter twenty-four: It’s All Coming Back to Me Now – Meat Loaf Chapter twenty-five: Start me Up – Rolling Stones Chapter twenty-six: Heaven Can Wait – Meat Loaf Chapter twenty-seven: Gotta Have a Reason – Bon Jovi Chapter twenty-eight: Strangers in the Wind – Bay City Rollers Chapter twenty-nine: All I Want from You – Kevin Costner and Modern West Chapter thirty: Five Minutes from America – Kevin Costner and Modern West Chapter thirty-one: Palisades – Kevin Costner and Modern West Chapter thirty-two: I Get a Rush – Bon Jovi Chapter thirty-three: Destination Anywhere – Jon Bon Jovi . -

Everybody Can Save a Life! Video Contest

Everybody Can Save A Life! Video Contest A unique initiative designed to create and distribute inspiring videos that promote Living Organ Donation through MatchingDonors.com. Sponsorship and Marketing Opportunities Sponsorship Opportunities: We are currently accepting sponsors for our Everybody Can Save A Life! video contest. All proceeds will go to help people get organ transplants. Benefits of Sponsorship: We expect huge visibility by Hollywood producers, the Hollywood film industry, national and international press, industry decision makers, Hollywood A-listers and millions of other people. Diamond Sponsorship: cost $65,000 - All Diamond Sponsors will receive sponsorship on all promotional materials, including the posting page of video entries and numerous other promotional benefits (see below). Each Diamond Sponsor will receive: Six tickets to attend the Hollywood Awards® Gala ceremony at the table generously donated to MatchingDonors.com by the Hollywood Awards®. Additional tickets can be purchased by Diamond Sponsors at $4,500 each. Dinner for six with the MatchingDonors.com contest judge of their choice. Based on availability. Their name/logo showcased on the top MatchingDonors.com full-page four color section of the Hollywood Awards® Gala Ceremony Program Book on the page generously donated by the Hollywood Awards®. A large (468x60 pixels) banner advertisement, name logo and link showcased on our MatchingDonors.com homepage, patient sign in page, and donor sign in page. The MatchingDonors.com homepage will be shown in any upcoming television shows about MatchingDonors.com. A banner advertisement showcased on the MatchingDonors.com contest web page. Recognition in all MatchingDonors.com contest related press releases. A banner advertisement showcased on any associated printed materials, social media tools (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, et al.) about the contest. -

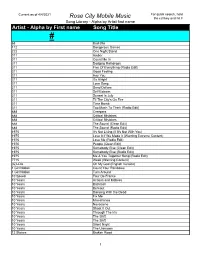

Alpha by First Name Song Title

Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title # 68 Bad Bite 112 Dangerous Games 222 One Night Stand 311 Amber 311 Count Me In 311 Dodging Raindrops 311 Five Of Everything (Radio Edit) 311 Good Feeling 311 Hey You 311 It's Alright 311 Love Song 311 Sand Dollars 311 Self Esteem 311 Sunset In July 311 Til The City's On Fire 311 Time Bomb 311 Too Much To Think (Radio Edit) 888 Creepers 888 Critical Mistakes 888 Critical Mistakes 888 The Sound (Clean Edit) 888 The Sound (Radio Edit) 1975 It's Not Living (If It's Not With You) 1975 Love It If We Made It (Warning Extreme Content) 1975 Love Me (Radio Edit) 1975 People (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Radio Edit) 1975 Me & You Together Song (Radio Edit) 7715 Week (Warning Content) (G)I-Dle Oh My God (English Version) 1 Girl Nation Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation Turn Around 10 Speed Tour De France 10 Years Actions and Motives 10 Years Backlash 10 Years Burnout 10 Years Dancing With the Dead 10 Years Fix Me 10 Years Miscellanea 10 Years Novacaine 10 Years Shoot It Out 10 Years Through The Iris 10 Years The Shift 10 Years The Shift 10 Years Silent Night 10 Years The Unknown 12 Stones Broken Road 1 Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title 12 Stones Bulletproof 12 Stones Psycho 12 Stones We Are One 16 Frames Back Again 16 Second Stare Ballad of Billy Rose 16 Second Stare Bonnie and Clyde 16 Second Stare Gasoline 16 Second Stare The Grinch (Radio Edit ) 1975. -

Catalogue Karaoké Mis À Jour Le: 29/07/2021 Chantez En Ligne Sur Catalogue Entier

Catalogue Karaoké Mis à jour le: 29/07/2021 Chantez en ligne sur www.karafun.fr Catalogue entier TOP 50 J'irai où tu iras - Céline Dion Femme Like U - K. Maro La java de Broadway - Michel Sardou Sous le vent - Garou Je te donne - Jean-Jacques Goldman Avant toi - Slimane Les lacs du Connemara - Michel Sardou Les Champs-Élysées - Joe Dassin La grenade - Clara Luciani Les démons de minuit - Images L'aventurier - Indochine Il jouait du piano debout - France Gall Shallow - A Star is Born Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen La bohème - Charles Aznavour A nos souvenirs - Trois Cafés Gourmands Mistral gagnant - Renaud L'envie - Johnny Hallyday Confessions nocturnes - Diam's EXPLICIT Beau-papa - Vianney La boulette (génération nan nan) - Diam's EXPLICIT On va s'aimer - Gilbert Montagné Place des grands hommes - Patrick Bruel Alexandrie Alexandra - Claude François Libérée, délivrée - Frozen Je l'aime à mourir - Francis Cabrel La corrida - Francis Cabrel Pour que tu m'aimes encore - Céline Dion Les sunlights des tropiques - Gilbert Montagné Le reste - Clara Luciani Je te promets - Johnny Hallyday Sensualité - Axelle Red Anissa - Wejdene Manhattan-Kaboul - Renaud Hakuna Matata (Version française) - The Lion King Les yeux de la mama - Kendji Girac La tribu de Dana - Manau (1994 film) Partenaire Particulier - Partenaire Particulier Allumer le feu - Johnny Hallyday Ce rêve bleu - Aladdin (1992 film) Wannabe - Spice Girls Ma philosophie - Amel Bent L'envie d'aimer - Les Dix Commandements Barbie Girl - Aqua Vivo per lei - Andrea Bocelli Tu m'oublieras - Larusso