The Genogram

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drawing a Genogram

PSDP—Resources and Tools: Drawing a genogram Funded by the Department for Education www.practice-supervisors.rip.org.uk Introduction Genograms are simple and effective to use Other learning tools in this section of the in supervision. This learning tool explains website (‘Using systemic questions in what they are and how they can be used supervision’ and ‘Social GGRRAAACCEEESSS to provide rich insights and reflections in and the LUUUTT model’) also complement supervision discussions. You don’t need to the information contained in this one and be an expert to use genograms. We hope would be useful to read in tandem. this tool will encourage you to use them with your supervisees. You can find a short film that shows a genogram being drawn and used in supervision on the website next to this tool. We suggest you watch the film after you’ve read through it. 2 Practice Tool: Drawing a genogram What is a genogram? A genogram is a visual tool which shows a This quote highlights how significant family tree of at least three generations. It is genograms can be for social work practice, used to give a pictorial representation of a given that they can help us to track and family system. reflect on the impact of different patterns of beliefs and behaviour through the Genograms are a foundational tool used generations within families. This includes in systemic practice, where there’s a focus the impact of adverse experiences on ‘on relationships’ and a recognition ‘that family functioning, as well as identifying individuals are always embedded in their relationships within the family system social context’ (Burns, 2018). -

Homelessness: a Qualitative Genogram Analysis of Trauma and Addictions

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2003 Homelessness: A qualitative genogram analysis of trauma and addictions Lorraine K Moss University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Moss, Lorraine K, "Homelessness: A qualitative genogram analysis of trauma and addictions" (2003). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1498. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/tuvj-ejsv This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOMELESSNESS: A QUALITATIVE GENOGRAM ANALYSIS OF TRAUMA AND ADDICTIONS by Lorraine K. Moss Bachelor of Science, Psychology University of Central Florida 2001 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Counseling Department of Counseling Greenspun College of Urban Affairs Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2003 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1414539 Copyright 2003 by Moss, Lorraine K. All rights reserved. UMI UMI Microform 1414539 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. -

Utilization of Genograms and Eco-Maps to Assess American Indian Families Who Have a Member with a Disability

DDCUMENT RESUME ED 333 60C EC 300 359 AUTHOR Goodluck, Charlotte Tsoi TITLE Utilization of Genograms and Eco-Maps To Assess American Indian Families Who Have a Member with a Disability. (Making Visible the Invisible.) Training Curriculum. INSTITUTION Northern Arizona Univ., Flagstaff. Native American Research and Training Center. PUB DATE 90 NOTE 78p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Instructional Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indians; Communication Skills; Diagrams; *Disabilities; *Evaluation Methods; Family History; *Family Relationship; *Family Structure; Genealogy; Interviews; Rehabilitation Programs; Systems Approach; Training IDENTIFIERS "Eno Maps; "Genograms ABSTRACT This training manual demonstrates the utilization of two family assessment tools with American Indian rehabilitation clients. The manual begins with an overview of general systems theory, family systems theory, and family assessment theory. The genogram is then defined as a type of family tree covering at least three generations, offering a map of a family's aspirations, patterns of behavior, roles, demographics, major life events, losses, births, abilities, disabilities, occupations, and communication and relationship patterns. Three types of genograms are disnussed. Eco-map assessment is then described as a visual drawing of all resources available in the family system, indicating relationships between the client and the various resources or people affecting the client's life. Instructions are offered for constructing an eco-map. Information is then offered to assist in developing .staff members' interviewing and communication skills during assessment. The training manual provides a list of abbreviations, a list of symbols foruse on genograms and eco-maps, a genogram interview schedule, informed consent forms, field procedures, and a workshop evaluation form. -

Influence of Family Function and Structure on Depression in Middle Aged Women Attending Federal Medical Centre, Owo

INFLUENCE OF FAMILY FUNCTION AND STRUCTURE ON DEPRESSION IN MIDDLE AGED WOMEN ATTENDING FEDERAL MEDICAL CENTRE, OWO A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE NATIONAL POST GRADUATE MEDICAL COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE COLLEGE IN FAMILY MEDICINE BY ORJI, ELOHO JOY MB, BS (PORT HARCOURT) 2000 APRIL 2017 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this research work is original except where it is otherwise stated. It has not been presented to any other college for the purpose of award of any degree or fellowship neither has it been previously published. ---------------------------------- ------------------ - DR. ORJI ELOHO JOY DATE 2 CERTIFICATION We certify that this study has been carried out by DR. ORJI ELOHO JOY of The Department of Family Medicine, Federal Medical Centre, Owo, Nigeria. The writing of this dissertation was also duly supervised by us. ------------------------------------------------------- DR. O. O. AKINBOBOYE MB, BS, FWACP, FMCGP(Nig) Consultant family Physician Department of Family Medicine Federal Medical Centre, Owo, Ondo State, Nigeria. ------------------------------------------------------ DR. ADESOKAN AO Consultant Psychiatrist Department of Psychiatry Federal medical Centre Owo, Ondo state, Nigeria. 3 DEDICATION This book is dedicated to the GLORY OF GOD and for the benefit of mankind. 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My special thanks goes first and foremost to my creator, the Lord God Almighty who has been the ever present help for me in my entire life’s endeavours for making the actualization of this work a reality. I sincerely appreciate my wonderful husband, Dr Stanley Orji, who has been of great help and support during this period; also my lovely children Ucheoma, Nkirukamma, Ekele, Otuto and Chimaobiya for their understanding and patience through the period of this training. -

The Cultural Genogram: Key to Training Culturally Competent Family Therapists

Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 1995, Vol. 2 I, NO.3,227-237 THE CULTURAL GENOGRAM: KEY TO TRAINING CULTURALLY COMPETENT FAMILY THERAPISTS Kenneth V. Hardy Tracey A. Laszloffy Syracuse University Training programs committed to the development of culturally competent family therapists must discover ways to raise cultural awareness and increase cultural sensitivity. While awareness involves gaining knowledge of various cultural groups, sensitivity involves having experiences that challenge individuals to explore their personal cultural issues. This article outlines how the cultural genogram can be used as an effectivetraining tool to promote both cultural awareness and sensitiv- ity. To meet the demands of a changing world, it will be imperative for family therapy training programs to devote greater attention to preparing culturally competent therapists. Unfortunately, current efforts to prepare culturally competent therapists are skewed heavily toward promoting cultural “awareness” while neglecting the importance of cultural “sensi- tivity.” This occurs primarily through the use of multicultural training models that rely heavily on providing trainees with multicultural content, with far less emphasis upon pro- moting meaningful multicultural experiences. Although it is beneficial for trainees to receive exposure to content highlighting the unique aspects of various cultural groups, it is rare that such knowledge readily translates into sensitivity. The content-focused approach to multicultural education overemphasizes the characteristics of various cultural groups while ignoring the importance of the trainees’ perceptions of and feelings toward their respective cultural backgrounds. As a result, train- ees are rarely challenged to examine how their respective cultural identities influence un- derstanding and acceptance of those who are both culturally similar and dissimilar. -

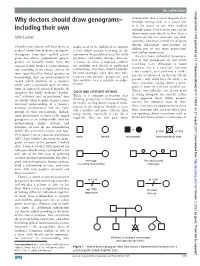

Why Doctors Should Draw Genograms–Including Their

On reflection Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/postgradmedj-2017-135241 on 21 August 2017. Downloaded from information into a small diagram than Why doctors should draw genograms– through writing and, as a visual aid, it is far easier to use than reading including their own through prose. If necessary, you can jot down some core details in less than a John Launer minute on the first occasion you meet someone, and then extend the diagram during subsequent conversations by Virtually every doctor will have learnt at might need to be mobilised to support adding one or two more generations medical school how to draw a genogram. a frail elderly person returning to the and further annotation. Genograms (sometimes spelled geneo- community. In specialised areas like child An even more unhelpful misconcep- grams but always pronounced ‘gene-o- psychiatry and family therapy, there are tion is that genograms are just about grams’) are basically family trees, but a variety of other recognised symbols recording facts. Although in many annotated with further relevant informa- for marking such details as conflictual instances this is a necessary function tion according to the clinical context. In relationships, but these should probably – for example, to record that a child’s some specialties like clinical genetics or be used sparingly, since they may only parents are divorced, or that an elderly haematology, they are used routinely to represent one person’s perspective, and person’s only child lives far away – in record which members of a patient’s they could be seen as intrusive or judge- most situations taking down a geno- family carry a particular gene or suffer mental. -

Redalyc.Genogram: Tool for Exploring and Improving Biomedical And

International Journal of Psychological Research ISSN: 2011-2084 [email protected] Universidad de San Buenaventura Colombia Cuartas Arias, Jorge Mauricio Genogram: tool for exploring and improving biomedical and psychological research International Journal of Psychological Research, vol. 10, núm. 2, 2017, pp. 6-7 Universidad de San Buenaventura Medellín, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=299052071001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Int. j. psychol. res, Vol. 10 (2) 6-7 2017 DOI 10.21500/20112084.3177 Genogram: tool for exploring and improving biomedical and psychological research Genograma: una herramienta para explorar y mejorar la investigacion´ biomedica´ y psicologica´ Jorge Mauricio Cuartas Arias1* 1Faculty of psychology, Universidad de San Buenaventura, Medell´ın, Colombia. *Corresponding author: [email protected] Currently, genograms have become a basic and funda- environmental context. mental tool used to graphically represent a detailed record Additionally, genograms allow us to make inferences of family information. Their construction should include not about prognoses, the presence of distinctive clinical subtypes, only basic details and family structure, but also information and the evolution of symptoms. This is possible when clinical that can outline different approaches for both research and patterns or frequent behaviors can be identified in a patient clinical intervention. and are shared with other close family members. One ex- In basic and biomedical research, genealogies are a funda- ample of this is the findings on neurocognitive performance mental resource for the evaluation of genetic homogeneity of in the index case and other family members, suggesting the a population or sample group. -

Using the Genogram in Social Work Practice with Families to Teach Systems Theory, Cultural and Ethnic Transmissions, Intergene

Genograms 30 Genograms and African American Families: Employing Family Strengths of Spirituality, Religion, and Extended Family Network Annie McCullough Chavis1 Abstract This article explores how genograms can serve as a multigenerational assessment for understanding family functioning and family processes. First, the author discusses how genograms are useful when depicting significant cultural patterns, beliefs, values, traditions, and family strengths in African American families. Next, she describes an integrated genogram model that may help social workers and practitioners recognize and employ recognized culturally connected family strengths and resources for work with African American families. Finally, a specific example of an intergenerational family genogram illustrates how practitioners can focus on extended family networks, spirituality, and religion as family strengths and resources in African American families. Key Words: Genogram, African American families, family strengths, extended family network, spirituality, religion, family resources, intergenerational 1Annie McCullough Chavis, Ed.D., CMSW, ACSW is Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work, Fayetteville State University, 1200 Murchison Road, Fayetteville, NC, 28301. Electronic mail may be sent via the Internet to [email protected]. Author’s Note: I would like to thank Sabrina McKeithan, Teaching & Learning Instructional Technologist at Fayetteville State University, and Thomas W. Blume, editorial advisor, for their help with constructing the genogram. The genogram is a valuable assessment tool used by social workers, therapists, counselors, and practitioners (Hartman & Laird, 1983; Hartman, 1995; McGoldrick & Gerson, 1985). Diagrammatically, the genogram is an intergenerational map of three or more generations of a family and a primary assessment tool that focuses on intergenerational patterns and relationships among family members (Goldenberg & Goldenberg, 2000; Hartman, 1995; McGoldrick, Gerson, & Shellenberger, 1999). -

Genogram Visualization Using Social Network Approach for Medical Family Tree

GENOGRAM VISUALIZATION USING SOCIAL NETWORK APPROACH FOR MEDICAL FAMILY TREE SITI FATIMAH BINTI BOKHARE UNIVERSITI SAINS MALAYSIA 2018 GENOGRAM VISUALIZATION USING SOCIAL NETWORK APPROACH FOR MEDICAL FAMILY TREE by SITI FATIMAH BINTI BOKHARE Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science August 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT In the name of Allah, the most gracious and the most merciful. Alhamdulillah, highest praise to Allah for his wills that gave me the strength and patience to complete this thesis and made all things possible Foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr Wan Mohd Nazmee Wan Zainon as my supervisor and my co-supervisor, Prof. Dr Abdullah Zawawi Talib for their continuous support of my master study and research, for their patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge. Their guidance helped me in all the time of research and writing of this thesis. I could not have imagined having a better supervisor and co-supervisor for my master study. I acknowledge, appreciate, and return the love and support of my family, without whom I would be lost, especially to my husband Fadzli and my son Muhammad who have been my emotional anchors through not only during my study years, but my entire life. Both my parents, siblings and their family have also become an important part of my world. I am forever indebted to all my family members for their affection, support, and constant encouragement. Thanks to many current and former people and all lab members at the School of Computer Sciences USM for their help and friendship over the years. -

Working with the Whole Family: What Case Files Tell Us About Social Work Practices

This is a repository copy of Working with the Whole Family: What Case Files tell us about Social Work Practices. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/111181/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Laid, S., Morris, K.M. orcid.org/0000-0002-1245-1023, Archard, P. et al. (1 more author) (2017) Working with the Whole Family: What Case Files tell us about Social Work Practices. Child and Family Social Work. ISSN 1356-7500 https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12349 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Working with the Whole Family: What Case Files tell us about Social Work Practices Abstract Practice theories to support child protection social work in the United Kingdom, as in the United States and Australia, are being squeezed out by a focus on performance targets and procedural timescales. This study examines an innovative programme designed to reverse this trend initiated by an English local government authority. -

The Power of the Genogram.Pdf

The power of the genogram Matthew Adam Introduction Vignettes mother, uncertain about how to react. Recently, while working in my professional Family 1 Jessica’s mother stated that while neither context, a Tier 4 inpatient hospital, I was ‘Jessica’, a 16-year-old girl, had been sexually of her girls had heard these stories they struck by a bolt of metaphorical lightning abused by her father when she was 11 years needed to be told and that she explained that drew my att ention to the seemingly old until she was 14 years old. She had been that she harboured guilt and responsibility innocuous tool many family therapists use referred to the inpatient unit for deliberate and for Jessica’s subsequent abuse. Th e on a day-to-day basis, the genogram (Carter severe self-harming behaviour and for having family story had suddenly become & McGoldrick, 1998). made two serious suicide att empts by over- overwhelmingly powerful and frightening Th roughout my clinical training I dosing on paracetamol. Aft er a few months and the young girls visibly withdrew inside understood the genogram’s value as Jessica’s mood lift ed and she developed coping themselves for the duration of the session. an assessment tool, an opportunity to strategies to help her deal with her thoughts of develop an awareness of patt erns or scripts self-harm and it was decided that home leave Family 2 in families, oft en trans-generationally, could begin. Visits home from the hospital ‘Suzanne’, a 16-year-old diagnosed and to use this feedback as a basis for the seemed to coincide with overdoses in the with anorexia nervosa, att ended a family formulation of hypotheses which would, community and the family oft en returned Jes- therapy session with her mother and of course, form the framework for the sica back to the unit distraught and angry. -

Genograms Practical Tools Forfamiy Physicians

El Genograms Practical tools forfamiy physicians IAN WATERS, MSW, CSW WILLIAM WATSON, MD, CCFP WILLIAM WETZEL, MSW GENOGRAM IS A VERSATILE Family systems medicine clinical tool that can help During the last decade, research has family physicians inte- demonstrated a relationship between grate a patient's family family functioning and the physical and information into the med- emotional well-being of an individual ical problem-solving process for better patient.' Family systems medicine has patient care. Physicians in primary care promoted a family orientation to patient SUMMARY often have to treat patients with serious care by developing several assessment A geogram can help a physidan medical illnesses (eg, cardiovascular dis- tools that incorporate both family ietegrate a patient's family and information into the medical ease, diabetes, hypertension) in combi- psychosocial information into medical proMmn-solving process for nation with psychosocial problems care. These family assessment tools letter patient care. A genogram (eg, domestic violence, substance abuse, include the family APGAR, family circle allows a physid. to obtim relationship difficulties). Knowledge of method,2 genogram,3 PRACTICE,4 and medicol and psychosodal both biomedical and psychosocial issues FIRO5 models. information from . patint is needed to diagnose and manage these Physicians using a family systems easily aid, as a result, to have a patients. The family genogram (family medicine orientation have found that hifer understanding of the tree) offers a unique opportunity for creating a diagram of a family's health context of the presenting obtaining family medical and social his- care problems assists them in managing symptoms. tory from patients more easily, and for many of their patients' health care con- expanding a family physician's under- cerns.