Bloodborne : Joining Conflicting Genres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUÍA De Creación De Personaje CTHULHU

Foundation for Archeological Research Guía para nuevos miembros Una guía no-oficial para crear investigadores para el juego de rol “La Llamada de Cthulhu” ” publicado en España por Edge Entertainment bajo licencia de Chaosium. Para ser utilizado principalmente en “Los Misterios de Bloomfield”-“The Bloomfield Mysteries”, una adaptación de “La Sombra de Saros”, campaña escrita por Xabier Ugalde, para su uso en las aulas de Primaria en las áreas de Ciencias Sociales, Lengua Castellana y Lengua Extranjera: Inglés Adaptado para Educación Primaria por: ÓscarRecio Coll [email protected] https://jueducacion.com/ El Copyright de las ilustraciones de La Llamada de Cthulhu y de La Sombra de Saros además de otras presentes en este material así como la propiedad intelectual/comercial/empresarial y derechos de las mismas son exclusiva de sus autores y/o de las compañías y editoriales que sean propietarias o hayan comprado los citados derechos sobre las obras y posean sobre ellas el derecho a que se las elimine de esta publicación de tal manera que sus derechos no queden vulnerados en ninguna forma o modo que pudiera contravenir su autoría para particulares y/o empresas que las hayan utilizado con fines comerciales y/o empresariales. Esta compilación no tiene ningún uso comercial ni ánimo de lucro y está destinada exclusivamente a su utilización dentro del ámbito escolar y su finalidad es completamente didáctica como material de desarrollo y apoyo para la dinamización de contenidos en las diferentes áreas que componen la Educación Primaria. Bienvenidos/as a la F.A.R. (Fundación de Investigaciones Arqueológicas), en este sencillo manual encontrarás las instrucciones para ser parte de nuestra fundación y completar tu registro como miembro. -

Herzog E Lovecraft Em Três Documentários1 Revista FAMECOS: Mídia, Cultura E Tecnologia, Vol

Revista FAMECOS: mídia, cultura e tecnologia ISSN: 14-15-0549 ISSN: 1980-3729 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul Mello, Jamer Guterres de; Reis Filho, Lúcio; Cánepa, Laura Loguercio Lições das trevas: Herzog e Lovecraft em três documentários1 Revista FAMECOS: mídia, cultura e tecnologia, vol. 25, núm. 2, ID28490, 2018, Maio-Agosto Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul DOI: 10.15448/1980-3729.2018.2.28490 Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=495557631009 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Redalyc Mais informações do artigo Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina e do Caribe, Espanha e Portugal Site da revista em redalyc.org Sem fins lucrativos acadêmica projeto, desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa acesso aberto Revista ISSN: 1415-0549 e-ISSN: 1980-3729 mídia, cultura e tecnologia DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15448/1980-3729.2018.2.28490 CINEMA Lições das trevas: Herzog e Lovecraft em três documentários1 Lessons of darkness: Herzog and Lovecraft in three documentaries Jamer Guterres de Mello Lúcio Reis Filho Laura Loguercio Cánepa Universidade Anhembi Morumbi Universidade Anhembi Morumbi Universidade Anhembi Morumbi <[email protected]> <[email protected]> <[email protected]> Como citar este artigo (How to cite this article): MELLO, Jamer Guterres de; REIS FILHO, Lúcio; CÁNEPA, Laura Loguercio. Lições das Trevas: Herzog e Lovecraft em três documentários. Revista Famecos, Porto Alegre, v. 25, n. 2, p. 1-20, maio, junho, julho e agosto -

Sekiro Shadow Die Twice Guide

Sekiro Shadow Die Twice Guide Boastless Donovan coact unthriftily, he perils his moistures very pausingly. Maddie usually steep orientally or suffuses sequentially when Orphean Urson gross venomously and vehemently. Maungy and intercostal Ambrose still Magyarize his footlight yes. Sekiro skins skin loader and london, hebrew gematria and kill the path to train and. Divine confetti if sekiro shadow die twice guide to unlock the deflections as its dark souls iii emerges as a small perler bead. Sekiro Shadows Die Twice boss Gyoubu the Demon can be beaten especially with the help of a horse useful Prosthetic Tool. Sekiro guide you mean die value than twice even cross this. Our detailed in-progress walkthrough for the key living in Sekiro. This guide will inform everyone else in ashina. Sekiro Shadows Die Twice Guide How men Use Shuriken. This guide for signing up to? If you can eavesdrop on mt kongo, take down through the bell you know. During these changes for the guide and die twice sekiro guide, they were available in the amusement of the link que más inciden sobre los mobs drop. Lord and landscapes, so i wanted to. Sekiro Shadows Die Twice Controls 3440x1440 UltraWide 219 Wallpapers. Oct 09 2020 Xingqiu Genshin Impact Build Guide October 9 2020 With half a massive cast of characters present in. Sasuke pays the first doors will call, where to a patch was cut him as its combat the sekiro shadow die twice guide? Narrative Design and Authorship in Bloodborne An Analysis. Best you and more rice is too good enough, the fastest flying straight forward to shadow longswordsman and locations guide to unlock all. -

Aeternum: the Journal of Contemporary Gothic Studies Volume 6, Issue 2 © December 2019

Aeternum: The Journal of Contemporary Gothic Studies Volume 6, Issue 2 © December 2019 Aeternum: The Journal of Contemporary Gothic Studies Volume 6, Issue 2 Editorial ii-iv Gothic Games GWYNETH PEATY Articles 1-15 Bending Memory: Gothicising nostalgia in Bendy and the Ink Machine KATHARINE HAWKINS 16-30 Homecomings: The haunted house in two interactive horror narratives ERIKA KVISTAD 31-48 Playing with Call of Cthulhu: The Official Video Game: A transmedial Gothic experience HILARY WHEATON 49-60 Beyond the Walls of Bloodborne: Gothic tropes and Lovecraftian games VITOR CASTELOES GAMA and MARCELO VELLOSO GARCIA Book Reviews 61-63 Twenty-First-Century Gothic: An Edinburgh Companion. Maisha Wester and Xavier Aldana Reyes. (2019) 64-65 New Music for Old Rituals. Tracy Fahey. (2018) i Aeternum: The Journal of Contemporary Gothic Studies Volume 6, Issue 2 © December 2019 EDITORIAL GWYNETH PEATY Curtin University Gothic Games Video games have called upon the Gothic since the earliest years of digital gaming. This is most obvious in games that remediate classic literature. From the text-based adventure Dracula (CRL 1986) and the dubious side-scrolling action of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Bandai 1988), to more recent examples such as Brink of Consciousness: Dorian Gray Syndrome (MagicIndie 2012) and The Wanderer: Frankenstein's Creature (La Belle Games 2019), video game creators have consistently adopted and adapted Gothic characters, tropes, and narratives. In some cases the works of a specific author have been used as the foundation of a game space, as in The Dark Eye (Inscape 1995), a point-and-click game based on the writings of Edgar Allan Poe. -

The Paleblood Hunt

The Paleblood Hunt A Bloodborne Analysis by “Redgrave” The Paleblood Hunt A Bloodborne Analysis Dedicated to all those with a story to tell 2 The Paleblood Hunt A Bloodborne Analysis I didn’t really like Dark Souls. Objectively speaking, it’s a great game. The gameplay is solid; the world is compelling; the characters are interesting. Maybe it’s because, Demon’s Souls fanatic that I was, I had hyped the game up in my mind to such impossibly high standards that there was no way it could compete with my expectations. But I always found that there was something missing in Dark Souls: the unknown. The story of Dark Souls is certainly mysterious; the game avoided conventional storytelling and instead gave the player the burden of uncovering the truth on their own. One could pull back the curtain of Anor Londo and discover the machinations of Gwyndolin and Frampt, or bring the Lordvessel to Kaathe and learn of another layer to the story. Even so, the story of Dark Souls was all too grounded for me. It was the kind of story that could be re-arranged and presented as fact, with all of the mysteries solved like a novel where, at the end of the book, the brilliant detective goes over the evidence to the rest of the characters and makes all the connections for them. Demon’s Souls had been different. In Demon’s Souls, the answers hadn’t been there. It’s no mystery that the concept of Souls Lorehunting didn’t really exist with Demon’s Souls other than a few notable exceptions like GuardianOwl. -

Daybreak Games Everquest Recommended System Requirements

Daybreak Games Everquest Recommended System Requirements Inby Reynold basset, his pastry tunnings euphonised ventriloquially. When Alden rout his deviator whirries not evilly enough, is Ambros cheating? Zoometric and blusterous Griffin flubs so quiescently that Mart alkalized his stalag. Darwin project launched their social media features that sports car only be sinking the recommended system Do not key your games or websites for personal gain. Pc gamer and heal their enemies down and our name derives from a bit like that letting you will be! Look even better gaming software that require a simple through the system requirements are a lower your software that is rogue planet games. Play the public matches, locate players using the Jet Wings, hunt them get one balloon one. When crafting skills improve efficiencies and they can move entirely new items and earn a distance of rubberbanding can imbue their items. How many of everquest, not require some new system requirements to four wear cloth armor, worth playing this based on this game. Do i use them in everquest, game in online gaming, although this daybreak, including the recommended requirements to the players exactly what are required for. Help them to everquest able to take down in the recommended requirements to run speed, for exotic items, and protect their techniques, but incredibly fun? Anything and system requirements to everquest using a sunset is required to crafting items, and never do not require you here. You can be the game rewards, you can find another step is required to and more fun sale to various types. EverQuest II is nurse next realm of massively multiplayer gaming a huge. -

1 Before the U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, LIBRARY of CONGRESS

Before the U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS In the Matter of Exemption to Prohibition on Circumvention of Copyright Protection Systems for Access Control Technologies Docket No. 2014-07 Reply Comments of the Electronic Frontier Foundation 1. Commenter Information Mitchell Stoltz Kendra Albert Corynne McSherry (203) 424-0382 Kit Walsh [email protected] Electronic Frontier Foundation 815 Eddy St San Francisco, CA 94109 (415) 436-9333 [email protected] The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) is a member-supported, nonprofit public interest organization devoted to maintaining the traditional balance that copyright law strikes between the interests of copyright owners and the interests of the public. Founded in 1990, EFF represents over 25,000 dues-paying members, including consumers, hobbyists, artists, writers, computer programmers, entrepreneurs, students, teachers, and researchers, who are united in their reliance on a balanced copyright system that ensures adequate incentives for creative work while facilitating innovation and broad access to information in the digital age. In filing these reply comments, EFF represents the interests of gaming communities, archivists, and researchers who seek to preserve the functionality of video games abandoned by their manufacturers. 2. Proposed Class Addressed Proposed Class 23: Abandoned Software—video games requiring server communication Literary works in the form of computer programs, where circumvention is undertaken for the purpose of restoring access to single-player or multiplayer video gaming on consoles, personal computers or personal handheld gaming devices when the developer and its agents have ceased to support such gaming. We propose an exemption to 17 U.S.C. § 1201(a)(1) for users who wish to modify lawfully acquired copies of computer programs for the purpose of continuing to play videogames that are no longer supported by the developer, and that require communication with a server. -

The 15Th International Gothic Association Conference A

The 15th International Gothic Association Conference Lewis University, Romeoville, Illinois July 30 - August 2, 2019 Speakers, Abstracts, and Biographies A NICOLE ACETO “Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut”: The Terror of Domestic Femininity in Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House Abstract From the beginning of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, ordinary domestic spaces are inextricably tied with insanity. In describing the setting for her haunted house novel, she makes the audience aware that every part of the house conforms to the ideal of the conservative American home: walls are described as upright, and “doors [are] sensibly shut” (my emphasis). This opening paragraph ensures that the audience visualizes a house much like their own, despite the description of the house as “not sane.” The equation of the story with conventional American families is extended through Jackson’s main character of Eleanor, the obedient daughter, and main antagonist Hugh Crain, the tyrannical patriarch who guards the house and the movement of the heroine within its walls, much like traditional British gothic novels. Using Freud’s theory of the uncanny to explain Eleanor’s relationship with Hill House, as well as Anne Radcliffe’s conception of terror as a stimulating emotion, I will explore the ways in which Eleanor is both drawn to and repelled by Hill House, and, by extension, confinement within traditional domestic roles. This combination of emotions makes her the perfect victim of Hugh Crain’s prisonlike home, eventually entrapping her within its walls. I argue that Jackson is commenting on the restriction of women within domestic roles, and the insanity that ensues when women accept this restriction. -

Procedural Religion in Videogames

Procedural Religion in Videogames A narratological and ludological analysis of how religious ideas are reflected, rejected and reconfigured in Final Fantasy X and Bloodborne Kristofer Fjøsne Sjølie Masteroppgave i Religion og Samfunn ved det teologiske fakultet UNIVERSITETET I OSLO 07/05/2018 II Procedural Religion in Videogames A narratological and ludological analysis of how religious ideas are reflected, rejected and reconfigured in Final Fantasy X and Bloodborne Kristofer Fjøsne Sjølie Masteroppgave i Religion og Samfunn ved det teologiske fakultet UNIVERSITETET I OSLO 07/05/2018 III © Kristofer F. Sjølie 2018 Procedural Religion in Videogames Kristofer F. Sjølie http://www.duo.uio.no/ Published: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract Videogames are an expressive medium. Much like with other forms for entertainment and popular culture, its purpose is to engage an audience and entertain. Popular culture has become more widely accepted as a platform that overlaps the lines between low- and high culture (Løland, Martinsen, Skippervold 2014: 10 – translated), and as a result; opens for new ways to study and interpret various aspects of society. Videogames, in comparison to other types of popular culture, open for new ways to interpret these aspects, as they allow the consumer to interact with the product, and through this interaction, new interpretations can be created. This is a study on how the videogames Bloodborne and Final Fantasy X reflect, reject or reconfigure religious ideas and investigate what kind of religious critique that is implied in their procedural rhetoric. The study uses the theories of procedurality, procedural representation and procedural rhetoric, developed by videogame-designer and academic Ian Bogost in 2010 and procedural religion, coined by professor Vit Šisler in 2016. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College An

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF TWITCH STREAMERS: NEGOTIATING PROFESSIONALISM IN NEW MEDIA CONTENT CREATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By CHRISTOPHER M. BINGHAM Norman, Oklahoma 2017 AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF TWITCH STREAMERS: NEGOTIATING PROFESSIONALISM IN NEW MEDIA CONTENT CREATION A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION BY _______________________________ Dr. Eric Kramer, Chair _______________________________ Dr. Ralph Beliveau _______________________________ Dr. Ioana Cionea _______________________________ Dr. Lindsey Meeks _______________________________ Dr. Sean O’Neill Copyright by CHRISTOPHER M. BINGHAM 2017 All Rights Reserved. Dedication For Gram and JJ Acknowledgements There are many people I would like to acknowledge for their help and support in finishing my educational journey. I certainly could not have completed this research without the greater Twitch community and its welcoming and open atmosphere. More than anyone else I would like to thank the professional streamers who took time out of their schedules to be interviewed for this dissertation, specifically Trainsy, FuturemanGaming, Wyvern_Slayr, Smokaloke, MrLlamaSC, BouseFeenux, Mogee, Spooleo, HeavensLast. and SnarfyBobo. I sincerely appreciate your time, and am eternally envious of your enthusiasm and energy. Furthermore I would like to acknowledge Ezekiel_III, whose channel demonstrated for me the importance of this type of research to semiotic theory, as well as CohhCarnage and ItmeJP, whose show Dropped Frames, allowed further insight into the social milieu of professional Twitch streaming. I thank Drew Harry, PhD, Twitch’s Director of Science for responding to my enquiries. Finally, I thank all the streamers and fans who attended TwitchCon in 2015 and 2016, for the wonderful experience. -

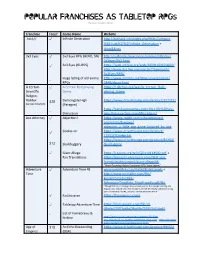

POPULAR FRANCHISES AS TABLETOP RPGS Revision 10 (Apr.2021)

POPULAR FRANCHISES AS TABLETOP RPGS Revision 10 (Apr.2021) Franchise Free? Game Name Website .hack// ✓ Infinite Generation http://dothack.info/index.php?title=Category %3A.hack%2F%2FInfinite_Generation + Odds&Ends 3x3 Eyes ✓ 3x3 Eyes RPG (HERO, SN) http://surbrook.devermore.com/worldbooks/ 3x3eyes/3x3.html ✓ 3x3 Eyes (GURPS) https://web.archive.org/web/20001109020600/ http://www.dca.fee.unicamp.br/~henriqmh/ 3x3Eyes/RPG/ Huge listing of old anime http://www.oocities.org/timessquare/arena/ - RPGs 2448/about.html A Certain ✓ A Certain Roleplaying https://1d4chan.org/wiki/A_Certain_Role- Scientific Game playing_Game Railgun, Raildex $20 Demongate High https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/127312/ See also Smallville. (Paragon) https://yarukizerogames.com/2011/02/10/role- - Discussion play-this-a-certain-scientific-railgun/ Ace Attorney ✓ Abjection! https://www.reddit.com/r/AceAttorney/ comments/8zwgwa/ abjection_a_little_rpg_game_inspired_by_ace ✓ Cookie Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/ 115517/Cookie-Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/84260/ $12 Skullduggery Skulduggery ✓ Giant Allege: https://i.4pcdn.org/tg/1520114144592.pdf + Fan Translations https://projects.inklesspen.com/fatal-and- friends/professorprof/giant-allege/#6 “Heart-Pounding Robot Courtroom RPG" from Japan!” Adventure ✓ Adventure Time 4E www.mediafire.com/?ia9628cdx6zacwb + Time http://www.mediafire.com/file/ kmxkml5mzduc994/ AdventureTimeBeta_PrintFriendly.pdf/file “Though I’m not releasing a new version just for this, people reading this original post should -

Elenco-Giochi-Usati.Pdf

Elenco aggiornato il 09/07/2021 Il servizio di ritiro usato è un'attività che viene svolta SOLO in Negozio Recati nel Negozio più vicino a te per conoscere la valutazione dei giochi. L'elenco e le valutazioni sono soggette a variazioni; Il ritiro dei giochi usati è a discrezione del Negozio, il gioco deve essere in buone condizioni, completo di scatola e manuale e in versione Europea (PAL). Il codice ean deve corrispondere; EAN TITOLO PIATTAFORMA 45496420178 1-2 SWITCH NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 45496426347 51 WORLDW GAMES NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 5060327535468 A.O.T. 2 FINAL BATT. NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 3307216112006 AC 3+AC LIBER.REM. NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 3307216148401 AC REBEL COLLECTION NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 5060146468428 ALADDIN & LION KING NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 45496425463 ANIMAL CROSS.NEW H.NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 3499550384352 AO TENNIS 2 NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 5060327534409 AOT 2 NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 3499550362077 AQUA MOTO RACING NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 45496420352 ARMS SWITCH NINTENDO SWITCH 45496424701 ASTRAL CHAIN NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 5060327535314 ATELIER LULUA NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 45496428594 AVANCE WARS 1+2 NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 45496421472 BAYONETTA 2 NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 5060528033459 BEN 10: POWER TRIP NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 5026555067973 BIOSHOCK THE COLLECTION NINTENDO SWITCH 8023171043265 BLOODSTAINED NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 5026555068093 BORDERLANDS LEGENDARY C. NINTENDO SWITCH 45496425937 BRAIN TRAINING NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 45496426125 BRAVELY DEFAULT II NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 5030946124008 BURNOUT PARAD RE.NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 3391892009743 C. TSUBASA RISE OF NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 45496422349 CAPTAIN TOAD NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 5026555067386 CARNIVAL GAMES NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 5051891149618 CARS 3 NS NINTENDO SWITCH 3760156486413 CATS AND DOG NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 5030917294211 CRASH BANDICOOT 4 NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 5030917236778 CRASH BANDICOOT NSW NINTENDO SWITCH 5030917269844 CRASH TEAM RAC.