Volume 5, Issue 2, April 2019 Articles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2016-17

Annual Report 2016-17 National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi 41st ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC FINANCE AND POLICY NEW DELHI Annual Report April 1st, 2016 – March 31st, 2017 Printed and Published by the Secretary, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (An autonomous research Institute under the Ministry of Finance, Government of India) 18/2, Satsang Vihar Marg, Special Institutional Area (Near JNU), New Delhi 110067 Tel. No.: 011 26569303, 26569780, 26569784 Fax: 91-11-26852548 email: [email protected] website: www.nipfp.org.in Edited & Designed by Samreen Badr Printed by: VAP email: [email protected] Tel: 09811285510 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1 2. Research Activities 5 2.1 Taxation and Revenue 2.2 Public Expenditure and Fiscal Management 2.3 Macroeconomic Aspects 2.4 Intergovernmental Fiscal Relations 2.5 State Planning and Development 2.6 New projects initiated 3. Workshops, Seminars, Meetings and Conferences 15 4. Training Programmes 17 5. Publications and Communications 19 6. Library and Information Centre 21 7. Highlights of Faculty Activities 25 Annexures I. List of Studies 2016-2017 51 II. NIPFP Working Paper Series 56 III. Internal Seminar Series 58 I V. List of Governing Body Members as on 31.03.2017 60 V. List of Priced Publications 64 VI. Published Material of NIPFP Faculty 68 VII. List of Staff Members as on 31.03.2017 74 VIII. List of Sponsoring, Corporate, Permanent, and Ordinary Members as on 31.03.2017 78 IX. Finance and Accounts 79 1. INTRODUCTION e 41st Annual Report of the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi is a reection of the Insti- tute’s work in the nancial year and accountability to the Governing Body and to the public. -

Student Absenteeism and School Health Programmes in Bihar

Working paper Student Absenteeism and School Health Programmes in Bihar Prabhat Ghosh Anjini Kochar March 2013 Student absenteeism and School Health Programs in Bihar By Prabhat Ghosh† and Anjini Kochar†† December 2012 (revised February 2013) †Asian Development Research Institute ††Stanford University This research was generously funded by a grant from the International Growth Center (Bihar Program). All opinions are those of the authors and they alone are responsible for any errors. The help and support received from Dr. Shaibal Gupta and researchers at ADRI is gratefully acknowledged. 1. Introduction This paper has two objectives. First, it provides information on student absenteeism in elementary school in two districts of the North Indian state of Bihar. While teacher absenteeism has received a significant amount of attention in the literature, less is known about student absenteeism. Knowledge of student absenteeism is critical for policies that attempt to improve schooling outcomes. It also helps the design of other programs that deliver services, such as health and nutrition, to children through schools. The extent of student absenteeism may critically affect coverage of any program delivered through schools. However, it is also necessary to understand the determinants of absenteeism since any systematic variation in absenteeism, across schools and amongst students within a school, will also influence the distribution of program benefits. A second objective is to assess the extent to which variation in coverage reflects components of the design of the program. This is particularly useful from a policy point of view, since it suggests methods whereby coverage can be enhanced, even given prevailing levels of student absenteeism. -

Caste, Land, and Migration: a Preliminary Analysis of a Village Survey in an Underdeveloped State in India

INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPING ECONOMIES IDE Discussion Papers are preliminary materials circulated to stimulate discussions and critical comments IDE DISCUSSION PAPER No. 334 Caste, Land, and Migration: A Preliminary Analysis of a Village Survey in an Underdeveloped State in India Yuko Tsujita* and Hisaya Oda** Abstract This paper explores migration from Bihar, one of the most underdeveloped states in India, by paying particular attention to social class (caste) and landholdings. After describing details of individual migrants, we present our preliminary findings on the determinants of migration, based on our field survey of 200 households in four villages in 2011. In terms of social class, Muslims are more likely to migrate, but Scheduled Castes do not show a high propensity to migrate as is stated in some of the existing literature where the underclass is said to be more mobile. In terms of landholdings, the probability that someone will migrate is high among the landless and smaller landholders but it decreases as the size of the landholding increases. However, as the size of the landholding increases still further, a reverse effect of landholding on decisions regarding migration moves in, with the decline in probability becoming less and less. This result confirms a non-linear relationship between landholdings and the decision to migrate. Some further research questions are raised in the paper. * Institute of Developing Economies ([email protected]) ** Ritsumeikan University ([email protected]) Keywords: migration, caste, land, India, Bihar JEL classification: O15, R23, Q15 The Institute of Developing Economies (IDE) is a semigovernmental, nonpartisan, nonprofit research institute, founded in 1958. -

Report on the Bihar PRI Finance Study

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University ICEPP Working Papers International Center for Public Policy 2011 Report on the Bihar PRI Finance Study Mark Rider Georgia State University, [email protected] Prabhat P. Ghosh Asian Development Research Institute, [email protected] Shaibal Gupta Asian Development Research Institute, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/icepp Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Rider, Mark; Ghosh, Prabhat P.; and Gupta, Shaibal, "Report on the Bihar PRI Finance Study" (2011). ICEPP Working Papers. 91. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/icepp/91 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the International Center for Public Policy at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in ICEPP Working Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. International Studies Program Working Paper 11-11 May 2011 Report on the Bihar PRI Finance Study Prabhat P. Ghosh Shaibal Gupta Mark Rider International Studies Program Working Paper 11-11 Report on the Bihar PRI Finance Study Prabhat P. Ghosh Shaibal Gupta Mark Rider May 2011 International Studies Program Andrew Young School of Policy Studies Georgia State University Atlanta, Georgia 30303 United States of America Phone: (404) 651-1144 Fax: (404) 651-4449 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://isp-aysps.gsu.edu Copyright 2006, the Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, Georgia State University. No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the copyright owner. -

Download Full Text

International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research ISSN: 2455-8834 Volume:03, Issue:07 "July 2018" DEVELOPMENT, SHARED FATE AND THE DEMAND OF ‘SPECIAL STATE’ STATUS IN INDIA MUKESH KUMAR JHA Research Scholar (PhD), Centre for the Study of Law and Governance, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi- 110067 ABSTRACT Recent demand of ‘Special State’ status in India, led by Bihar, has been subject to opinion based justice by both print and electronic media. A serious attempt has not been taken to interrogate, though critically, the nature of demand, the language of demand and the development model coming out of these demand(s). Unless the language(s) of demand itself is/are subject to critical investigation, it is futile to concentrate the narrower debate on the pros and cons of the demand of the ‘special state’ status in India. Keywords: Development, ‘Special State’ Status, shared fate, civil society, opinion(s), kamma- niyama, Bihar I The debate(s) around the demand of ‘Special State’ status, led by Bihar1, in India is/are under- researched but projected as over-conclusive. The content of the debate is primarily based on the framework of efficiency, viability or the mis(governance). Academic injustice is inherent in the debate as no single serious attempt has been undertaken to interrogate the nature, language and the reflected intentionality of the demand itself. As a result, the debate around the ‘Special State’ status has become the subject of opinion-based justice2. Keeping this in mind, the paper intends to interrogate the language of demand of the ‘special state’ status and the imagined 1 The state of Bihar becomes the focal point of the debate, in this essay, on the demand of special state status as the issue was raised very vociferously by the chief minister of Bihar Nitish Kumar even though the similar demands were raised by different states in different parts of India especially Orissa and West Bengal. -

Parachuters Vs. Climbers: Economic Consequences of Barriers to Political Entry in a Democracy

PLEASE DO NOT CIRCULATE WITHOUT PERMISSION FROM THE AUTHOR Parachuters vs. Climbers: Economic Consequences of Barriers to Political Entry in a Democracy Aaditya Dar∗ Please click here for the latest version Abstract How does political selection impact local economic growth? I study the role of a legisla- tor’s background prior to joining politics and conduct primary research to compile an original dataset of politicians’ biographies. Observing the entry route of politicians allows me to clas- sify them as ‘parachuters’ — those who are hereditary/dynastic or are part of the local socio- economic/cultural elite — and ‘climbers’, those who have made their way by rising up the ranks. I document three key results: one, barriers to political entry and post-colonial elite persistence have perverse economic consequences. Findings from a close election regression discontinuity design indicate that electing parachuters leads to 0.2 percentage point lower GDP growth per year compared to constituencies where climbers are elected. Two, a leader’s entry route is a sig- nicant feature of political selection, even after controlling for conventional ascriptive identities such as sex, religion and ethnicity. Three, there is suggestive evidence that the impact is driven by misallocation of bureaucratic resources and neither regulation of technology adoption nor factor price manipulation are the underlying mechanisms. Keywords: Political Economy, Political selection, Dynastic politics, Economic Development. JEL codes: D72, O12, N45 ∗George Washington University. Address: Department of Economics, 2115 G St., NW, Monroe 340, Washington, DC 20052; Email: [email protected]. I am indebted to Ashwani Kumar, Sanjay Kabir, Sanjay Paswan, Shaibal Gupta, Srikant and all anonymous respondents for their time and support in completing the data collection for this study. -

Poverty in Bihar: Pattern, Dimensions and Eradication Strategies

International Seminar on POVERTY IN BIHAR: PATTERN, DIMENSIONS AND ERADICATION STRATEGIES 18-20 April 2010, Patna A Report Organised by Institute for Human Development In association with Asian Development Research Institute Supported by United Nations Development Programme International Seminar on Poverty in Bihar Seminar Team Seminar Directors: Gerry Rodgers and Alakh N Sharma Seminar Coordinator: Amrita Datta Seminar Team: Joyita Ghose, Kasturi Mazumdar, Ashwani Kumar Documentation Team: Amrita Datta, Joyita Ghose, Kaushal Vidyarthee Seminar Adviser: Janine Rodgers Contents List of Abbreviations iv Preface v Seminar Report Section 1 1 Introduction 1 Section 2 3 Key Messages of the Seminar 3 Section 3 8 Inaugural Session 8 Session 1: International Round Table on Experiences and Success 13 Stories in Poverty Reduction Session 2: Identifying the Poor 17 Session 3: Key Dimensions of Poverty In Bihar 23 Session 4: Gender Disparities—How Important for Poverty? 27 Session 5: Experiences and Success Stories in Poverty Reduction in India 31 Session 6: Development Paths for Poverty Reduction 35 Session 7: Policies and Politics: The Framework for State 38 Interventions Session 8: Do Targeted Schemes and Programmes 41 Reach the Poor and Excluded? Session 9: Concluding Panel Discussion On Strategies, 45 Priorities And Prospects for Poverty Eradication in Bihar Annexure 1: Conference Programme 50 Annexure 2: List of Participants 56 International Seminar on Poverty in Bihar List of Abbreviations ADRI - Asian Development Research Institute APL - Above -

Bihar: What Went Wrong? and What Changed? Arnab Mukherji

Bihar: What Went Wrong? And What Changed? Arnab Mukherji and Anjan Mukherji Working Paper No. 2012-107 September 2012 National Institute of Public Finance and Policy New Delhi http://www.nipfp.org.in 1 DRAFT Bihar: What went wrong? And what changed? Arnab Mukherji1 and Anjan Mukherji2,3 Economy in Historical Perspective Bihar as a political entity, either as a kingdom, or as a state within the republic of India, has its own identity from the time written records were available (Thapar 1966; Rangarajan 1992). Noted historian, Romila Thapar, describes the history of ancient India as the history of ancient Bihar. Many achievements that India became renowned for, in education, governance, society, or religion, have their roots in Bihar. Significant achievements of Bihar in trade and economic engagement within the state and outside of the Indian sub-continent emerge from a past that appears to have left no living legacy in today’s Bihar--a past so alien as to be either simply forgotten or treated as being completely incredible.4 A more recognizable, if rather dramatic picture of Bihar is that seen in a 2010 article on change in the state: 1Assistant Professor, Center for Public Policy, Indian Institute of Management Bangalore. 2Jawaharlal Nehru National Fellow, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi, and Country Director, IGC India-Bihar Program. 3Acknowledgements: Presented at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy-Columbia University conference on “Growth, Poverty and Human Development in Indian States: Selected Issues” on August 7-8 at the India International Centre, New Delhi. We are indebted to our discussants Satya Das and Arunish Chawla for very helpful comments. -

Full Proposal Template

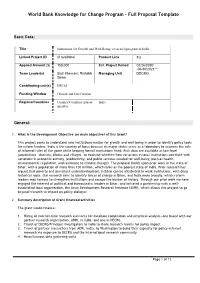

World Bank Knowledge for Change Program – Full Proposal Template Basic Data: Title Institutions for Growth and Well-Being: a research program in India Linked Project ID (if available) Product Line RA Applied Amount ($) 150,000 Est. Project Period 02/26/2020i -06/30/2021**ii Team Leader(s) Stuti Khemani; Rishabh Managing Unit DECMG Sinha Contributing unit(s) DECSI Funding Window Growth and Job Creation Regions/Countries Country/Countries (please India specify) General: 1. What is the Development Objective (or main objective) of this Grant? This project seeks to understand how institutions matter for growth and well-being in order to identify policy tools for reform leaders. India is the country of focus because its major states serve as a laboratory to examine the role of informal rules of the game while keeping formal institutions fixed. Rich data are available at low-level jurisdictions—districts, blocks and villages—to examine whether/how variations in local institutions correlate with variations in economic activity, productivity, and public services needed for well-being (such as health, environmental regulation, and resilience to climate change). The proposal builds upon prior work in the state of Bihar, with a population of more than 100 million, which ranks as the poorest state of India. Prior research has argued that poverty and persistent underdevelopment in Bihar can be attributed to weak institutions, with deep historical roots. Our research aims to identify forces of change in Bihar, and India more broadly, which reform leaders may harness to strengthen institutions and escape the burden of history. Through our prior work we have engaged the interest of political and bureaucratic leaders in Bihar, and initiated a partnership with a well- established local organization, the Asian Development Research Institute (ADRI), which allows this project to go beyond research to impact on policy dialogue. -

Newspaper Analysis and Summary– 27Th September

CURRENT AFFAIRS Newspaper Analysis and Summary – 27th September 2013 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Nuclear waste could supply 800 years of power -The Hindu In a drab one-story building here, set between an indoor tennis club and a home appliance showroom, dozens of engineers, physicists and nuclear experts are chasing a radical dream of Bill Gates: a new kind of nuclear reactor that would be fuelled by today’s nuclear waste, supply all the electricity in the United States for the next 800 years and, possibly, cut the risk of nuclear weapons proliferation around the world. The people developing the reactor work for a startup, TerraPower, led by Mr. Gates and a fellow Microsoft billionaire, Nathan Myhrvold. So far, it has raised tens of millions of dollars for the project, but building a prototype reactor could cost $5 billion — a reason Mr. Gates is looking for a home for the demonstration plant in rich and energy-hungry China. Today’s nuclear reactors run on concentrations of three to five per cent uranium 235, an enriched fuel that leaves behind a pure, mostly natural waste, uranium 238. (A uranium bomb runs on more than 90 per cent uranium 235.) In today’s reactors, some uranium 238 is converted to plutonium that is used as a small, supplemental fuel, but most of the plutonium is left behind as waste. In contrast, the TerraPower reactor makes more plutonium from the uranium 238 for use as fuel, and so would run almost entirely on uranium 238. It would need only a small amount of uranium 235, which would help kick-start the reaction. -

Adri Seminar Booklet.Indd

International Conference DEVELOPMENT AND GROWTH EXPERIENCE AND THEORIES MARCH 26-30, 2016 Sponsored by Indian Council of Social Science Research International Growth Centre World Bank Asian Development Research Institute them using an inter-disciplinary framework. These (ADRI)The was established in 1991 in Patna. The studies can be broadly divided into four categories motivation behind starting yet another Institute — (a) analytical, (b) diagnostic, (c) advocatory, and in Patna was not merely to expand social science (d) evaluative. ADRI also prepares the annual research, but to emphasise those dimensions of Economic Survey for the Government of Bihar and social science research which, although critical, till date 10 such surveys have been prepared. had received rather limited attention. In the above The organizational structure of ADRI includes, perspective, the objectives of ADRI are — (a) to besides the mother Institute, three more units — undertake academic research of direct relevance State Resource Centre (SRC) for adult education in to development efforts made by an individual or Bihar, sponsored by the Union Ministry of Human a group or the community itself involving policy Resource Development (MHRD), Jan Shikshan change, (b) to broaden the database of research and Sansthan (JSS), again sponsored by the MHRD, and its end use by involving as many classes of persons Centre for Economic Policy and Public Finance and institutions as possible, (c) to offer research (CEPPF), sponsored by the Government of Bihar. results in a more innovative, demystified and use- The Institute also has its office in Ranchi (Jharkhand), worthy form, and finally (d) to restore man to his which hosts an SRC for Jharkhand, sponsored by central position in social science research, and with the MHRD. -

Crisis States Programme Development Research Centre Www

1 crisis states programme development research centre www Working Paper no.3 COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH STATES OF CRISIS IN SOUTH ASIA April 2001 Copyright © Crisis States Programme, 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce any part of this Working Paper should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Programme, Development Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Programme Working papers series no.1 English version: Spanish version: ISSN 1740-5807 (print) ISSN 1740-5823 (print) ISSN 1740-5815 (on-line) ISSN 1740-5831 (on-line) 1 Crisis States Programme States of Crisis in India: Comparative research in Bihar and Madhya Pradesh Introduction The overarching aim of the research programme of the Crisis States DRC is ‘to provide new understanding of the causes of crisis and breakdown in the developing world and the processes of avoiding or overcoming them. {Our aim is to] investigate why some political systems and communities have broken down even to the point of violent conflict while others have not, and whether processes of globalisation have precipitated or helped to avoid crisis and social breakdown’. In this broad context of enquiry we propose to undertake comparative research on the Indian states of Bihar and Madhya Pradesh. These are two big states that have significant features in common, but while the first of them is commonly considered to be a ‘crisis state’, the second now has a reputation for effective and progressive government.