Volume 7, No. 1 Issue 19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acro Dance Express Overall Studio C

Nashville TN Regional Competition Mar 8-10, 2019 Studio Awards Winner of the Groove Award: Acro Dance Express Overall Studio Technique Award: Acro Dance Express Overall Studio Choreography Award: Ann Carroll School of Dance Professionalism Award: Studio 55 Dance ADCC Studio of Excellence Award: DIAMOND ACADEMY OF DANCE Inspired by Passion: Miss Amys Competitive Edge Overalls Novice Mini Solo Place Entry Title Studio 1 A Little Bit O Love Shining Starz Dance Studio 2 Im The Greatest Star Acro Dance Express 3 ROCK N ROLL Dance Force LLC 4 Baby Im a Star Ann Carroll School of Dance 5 Keep You Safe Shining Starz Dance Studio 6 Blow Studio 55 Dance 7 CRUISIN 4 A BRUISIN Heathers Dance Academy 8 Itsy Bitsy Milele Academy 9 Black and Yellow Showtyme Xtreme 10 Let Your Light Shine Shining Starz Dance Studio Intermediate Mini Solo Place Entry Title Studio 1 Heartburn EnPointe Performance Studio 2 State of Shock EnPointe Performance Studio 3 Shawty Get Loose All Starz Dance Academy of Franklin Novice Mini Duo/Trio Place Entry Title Studio 1 SPLASH N GO Dance Force LLC Intermediate Mini Duo/Trio Place Entry Title Studio 1 Breakin Dishes EnPointe Performance Studio Novice Mini Small Group Place Entry Title Studio 1 CANDY DIAMOND ACADEMY OF DANCE 2 Slam It Showtyme Xtreme 3 Slow Down Barfield School of Dance 4 Get Back Up Again Shining Starz Dance Studio 5 Troll time Miss Amys Competitive Edge Nashville TN Regional Competition Mar 8-10, 2019 6 Diamonds Jans School of Dance 7 Princesses Wanna Have Fun Barfield School of Dance 8 FRIEND LIKE ME DIAMOND -

Gold & Platinum Awards June// 6/1/17 - 6/30/17

GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS JUNE// 6/1/17 - 6/30/17 MULTI PLATINUM SINGLE // 34 Cert Date// Title// Artist// Genre// Label// Plat Level// Rel. Date// We Own It R&B/ 6/27/2017 2 Chainz Def Jam 5/21/2013 (Fast & Furious) Hip Hop 6/27/2017 Scars To Your Beautiful Alessia Cara Pop Def Jam 11/13/2015 R&B/ 6/5/2017 Caroline Amine Republic Records 8/26/2016 Hip Hop 6/20/2017 I Will Not Bow Breaking Benjamin Rock Hollywood Records 8/11/2009 6/23/2017 Count On Me Bruno Mars Pop Atlantic Records 5/11/2010 Calvin Harris & 6/19/2017 How Deep Is Your Love Pop Columbia 7/17/2015 Disciples This Is What You Calvin Harris & 6/19/2017 Pop Columbia 4/29/2016 Came For Rihanna This Is What You Calvin Harris & 6/19/2017 Pop Columbia 4/29/2016 Came For Rihanna Calvin Harris Feat. 6/19/2017 Blame Dance/Elec Columbia 9/7/2014 John Newman R&B/ 6/19/2017 I’m The One Dj Khaled Epic 4/28/2017 Hip Hop 6/9/2017 Cool Kids Echosmith Pop Warner Bros. Records 7/2/2013 6/20/2017 Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Pop Atlantic Records 9/24/2014 6/20/2017 Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Pop Atlantic Records 9/24/2014 www.riaa.com // // GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS JUNE// 6/1/17 - 6/30/17 6/20/2017 Starving Hailee Steinfeld Pop Republic Records 7/15/2016 6/22/2017 Roar Katy Perry Pop Capitol Records 8/12/2013 R&B/ 6/23/2017 Location Khalid RCA 5/27/2016 Hip Hop R&B/ 6/30/2017 Tunnel Vision Kodak Black Atlantic Records 2/17/2017 Hip Hop 6/6/2017 Ispy (Feat. -

Summer Institute Class of 2019 Individual Pieces Copyright ©2019 by Their Respective Authors

Multitudes edited by Siyanda Mohutsiwa The Summer Institute Class of 2019 Individual pieces copyright ©2019 by their respective authors. All rights reserved. International Writing Program 430 North Clinton Street, Shambaugh House Iowa City, Iowa 52245 United States of America www.iwp.uiowa.edu/programs/summer-institute Contents Foreword vi Peter Gerlach . vi Acknowledgements ix Contributors x 1 Dusk 1 Ghazal . 2 Azhar Wani . 2 Bargain Witchcraft . 3 Tanvi Chowdhary . 3 The Godfather . 14 Cherene Aniyan Puthethu . 14 Fair is Lovely . 18 Suyashi Smridhi . 18 2 Night 22 golden shovel ending in outer space after fleetwood mac .................... 23 Anna Sheppard . 23 What I Look To When Holdin' My Tongue . 24 Darius Christiansen . 24 i Contents Sandalwood . 25 Amna Shoaib . 25 Hermanita de la Mar . 29 KayLee Chie Kuehl . 29 3 Midnight 35 Table Etiquette . 36 Ashley Hajimirsadeghi . 36 Sapphirical Slick . 38 Darius Christiansen . 38 Almost Over . 40 Mahnoor Imran Sayyed . 40 Ward SSK 37: Eric . 50 Medha Faust-Nagar . 50 4 Small Hours 51 Altar . 52 Nyeree Boyadjian . 52 Capital ............................ 53 Nyeree Boyadjian . 53 Taxi . 54 Jishnu Bandyopadhyay . 54 Intruder . 65 Amna Shoaib . 65 The Reflection . 67 Fazila Nawaz . 67 5 Dawn 69 seasonal . 70 Anna Sheppard . 70 Hurricane . 72 Ashley Hajimirsadeghi . 72 Home from The Hospital . 73 Medha Faust-Nagar . 73 ii Contents Passing . 75 Aalia Waqas . 75 The Way Things Are . 76 Anna Magana . 76 House Key . 84 Martina Litty . 84 6 Noon 90 Absence . 91 Hafsa Nouman . 91 Six Months . 94 Payal Nagpal . 94 Yes, You Are . 97 Hafsa Ghani . 97 On Air . 100 Aalia Waqas . 100 The Safe Side . -

August 10, 1898

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. PORTLAND. MAINE, WEDNESDAY MORNING, AUGUST 10, 1898. THREE CENTS. ESTABLISHED JCNE 23, 1862-VOL. 35. ITOSSffffSSggt_PRICE NSW ADVERTISEMENTS. * Discussed by President and Advisers But I SPECIAL Not Given Out for Present. I -FOB- •' N ; •;•»---• * V*, ------ I SAGASTA. Ht)RSE STEAKS AND DOG CUTLETS. GOOD MOVE BUT RATHER LATE* TO ASSASSINATE Attaches Conditions to Her MONTEREY AT MANILA. Chief Item! on Bills.of Fare of Manila Din- Health of A Barcelona Anarchist Charged With the Spain Secretary Alger liooking After Job. ners. i 911 Prnoti Quito Camps. Au- Bayonne,France,August 9.—Despatches of Terms. Manila, July 30, via Hong Kong, lu uiaon uuuo August 0.—Secretary of food affects even [Washington, here from Madrid dated Acceptance gust 9.—-The scaroity received yester- Alger has determined to enforce every the richest classes in Manila now. There of aunounoe that the form of the of City Only Question the health day Span- Capture regulation whioh will improve is no nor flour ish acceptance of the Ame- meat, bread except very of the various camps of the army. The government's conditions involves the small reserves,chiefly laid under requisit- issued to- rican peace procla- Few Days. $2.98 following peremptory order was ion for the troops. The ews- mation of an armistice. This it is added, Spanish sold for 5.E8 and 6.98 day: censored admit that Fcrmerl) $4.93, must be first agreed to by the United pnpere though rigidly i;si. War Department, the famine and the unprecedented rains Adjutant General’s Office, States, and if the United States insists of are causing an epidemic. -

Morgan Wallen's 'Dangerous' Spends Fourth Week at No. 1 on Billboard

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; ENTERTAINMENTBrett Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayFEBRUARY 8, 2021 Page 1 of 25 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Morgan Wallen’s ‘Dangerous’ Spends Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music GroupFourth Nashville), debuts at No. Week1 on Billboard’s lion at audience No. impressions, 1 upon 16%). Billboard Top Country• Olivia AlbumsRodrigo’s chart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earned‘Drivers 46,000 License’ equivalent album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cordingLeads to Hot Nielsen 100 for Music/MRC 4th Data. 200 Albumsand total Country Airplay ChartNo. 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideWeek, The marks Weeknd Hunt’s second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chart &and CJ fourth Hit Top top 10 10. It follows freshman LP BY KEITH CAULFIELD Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- Montevallo• Super ,Bowl which Synch arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He vember 2014 and reigned for nine weeks. To date, followed with the multiweek No. 1s “In Case You Report: Sony/ATV Morgan Wallen’s Dangerous: The Double Album holds demand streams of the album’s songs), album sales Montevallo has earned 3.9 million units, with 1.4 Didn’t Know” (two weeks, June 2017), “Like I Loved Walking on Air at No. -

December 2016 Abington’S Newest Sports Team by Timmy Gallagher

Abington Senior High School, Abington, PA, 19001 December 2016 Abington’s Newest Sports Team by Timmy Gallagher Th is year, the Abington Paddle Tennis Club enters its second season and hopes are high for another great year. During the inaugural season, the team consisted of eleven players and it only played one match. Th is year, however, the team expects to double its number of players and have matches against a variety of diff erent schools. Th e team meets for practice every Monday and Wednesday during the months of January and February at their home courts at Huntington Valley Country Club. What is paddle tennis? Paddle tennis, also commonly called platform tennis or just paddle, is a variation of tennis that is played during winter. For most of its basic rules, paddle tennis follows the same rules as traditional tennis. One of the major diff erences between paddle tennis and regular tennis is that in paddle tennis, the court is one-third the size of a traditional tennis court and is surrounded by a wire screen. Th e ball can bounce off the screens and remain in play. Th is ability to play the ball off the wall is what diff erentiates how paddle tennis is played from traditional tennis. Th e smaller court, combined with the screen shots, causes paddle tennis to require much more quick thinking than traditional tennis. Other diff erences include the ball, which is dense and spongy, and, as the name implies, the solid, gritty paddle that is used in place of a typical tennis racquet. -

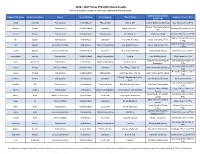

2016 - 2017 Texas PTA Reflections Results Full List of Students Judged at State-Level, Alphabetical by Last Name

2016 - 2017 Texas PTA Reflections Results Full list of students judged at state-level, alphabetical by last name. Student's School Name Student First Name Student Last Name Award Grade Division Arts Category Title of Work Region or Council PTA (Local PTA) Nicole Acevedo Participation Intermediate Photography Finding Me James E Williams Elementary Katy ISD Council of PTAs Bastrop Intermediate School Courtney Adams Participation Middle School Literature Where I am from... Bastrop ISD Council of PTAs PTA Linda Adams Participation Middle School Photography Lost My Mind Abell Junior High Midland ISD Council of PTAs Denton Community Council Eli Agawu Participation High School Literature This Is Not My Story Guyer High School PTA of PTAs Denton Community Council Eli Agawu Honorable Mention High School Music Composition Immigrant's Journey Guyer High School PTA of PTAs Lizbeth Aguillon Honorable Mention Middle School Visual Arts I'll Change the World Utley Middle School Rockwall Council of PTAs Luis Gabriel Aguirre Participation Middle School Music Composition Viaggio Ford Middle School Allen Council of PTAs Arapaho Classical Magnet Richardson ISD Council of Evan Ahlemeier Participation Intermediate Music Composition A Soccer Game Elementary PTAs Round Rock ISD Council of Nawal Ahmed Award of Merit Middle School Literature The "Thing" Called "It" Cedar Valley Middle School PTAs Round Rock ISD Council of Nawal Ahmed Participation Middle School Photography I Write My Story, Not You Cedar Valley Middle School PTAs A Pencil's Revolution: A Short -

{2017 Album} Meek Mill - DC4 Download Free

{2017 Album} Meek Mill - DC4 Download Free )( Meek Mill - {2017 Album} DC4 Download Free Album "Leak" Meek Mill DC4 Download Free Meek Mill - DC4 [MP3] )] Meek Mill - DC4 Album zip Download {2017 Album} Meek Mill DC4Full Album Leaked Download ^^ Meek Mill - DC4 {ZIP & Torrent} ^~ {^ZIP^} Meek Mill DC4 album telecharger (2017) free album Meek Mill - DC4 Download Song [.rar] Meek Mill DC4 album telecharger {MP3} Meek Mill DC4 2017 mp3 320 kbps For Free Meek Mill - DC4 Download Free DC4[ZIP] {} [ZIP] Meek Mill DC4 Download Song ~ ) Meek Mill - DC4 320 kbps Album [MP3] Meek Mill DC4(2017) free album Album zip Download Meek Mill - DC4 ZIP Album Download ^~ Meek Mill - DC4 (RAR) Zip RAR mp3 320 Meek Mill - DC4 ^Torrent free^ (RAR) Meek Mill DC4 Album 320 kbps mp3 {} Meek Mill - DC4 Full Album Download 2017 [] {MP3} Meek Mill DC4 Download Song Full Album Download DC4 l'album Leak rar Meek Mill - DC4 "Leak" [Album] Meek Mill DC4 Full Album Download (2017) download Meek Mill - DC4 (2017) free {Free Album} Meek Mill DC4 rar DC4[Album] [] {MP3} Meek Mill DC4 (2017) download Album zip Download DC4 2017 download() Meek Mill - [320 kbps] DC4 Album Leak [.zip] Meek Mill DC4(2017) Free iTunes )( Meek Mill - DC4 [Full Album} ^~ Meek Mill - DC4 -D DoCw4n llo'aldb uAmlb Luemak F ^r^e e{ A{MlbPu3m}} MMeeekk MMiilll DDCC44( 2A0lb1u7m) flreaek a lDbouwmn )l]o Madeek Mill - DC4 (Download) ~( [MP3] Meek Mill DC4 Album zip Download Descargar album Meek Mill - DC4 rar {MP3} Meek Mill DC4 zip free {ZIP & Torrent} Meek Mill DC4 Album mp3 320 Download album Torrent Meek Mill - DC4 Album zip Download DC4(RAR) }{ [.zip] Meek Mill DC4 zip download () Meek Mill - DC4 (2017) download {Free Album} Meek Mill DC4 Album Download Album zip Download Meek Mill - DC4 Download MP3 )] Meek Mill - DC4 {ZIP & Torrent} 2017 download Meek Mill - DC4 (2017) Album Download (ZiP) Meek Mill DC42017 mp3 320 kbps )] Meek Mill Artist: Meek Mill Album: DC4 Genre: Hip-Hop/Rap Original Release Date: 2017 Quality: 320 kbps Size: 113 MB Track Listing: 1.On the Regular 2.Blessed Up 3.Litty (feat. -

Richland County Business Service Center Open Businesses with Issued 2018 Richland County Business Licenses As of December 27, 2018 S.C

BSC Open Businesses with Issued 2018 Richland County Business LIcenses 12/27/2018 Richland County Business Service Center Open Businesses with Issued 2018 Richland County Business Licenses As of December 27, 2018 S.C. law provides that it is a crime to knowingly obtain or use personal information from a public body for commercial solicitation. Business Name Doing Business As Business Description (with NAICS code) Physical Location "A" Game Sports and Fitness 611620 -Sports and Recreation Instruction 508 Cartgate Cir Blythewood "Bundles" of Joy 448150 -Clothing Accessories Stores 1971 Lake Carolina Dr Columbia "Lady G" Creations, LLC 314999 -All Other Miscellaneous Textile Product Mills 1061 Sparkleberry Ln Ext Columbia "So" Fresh "So" Clean Janitorial Service 561720 -Janitorial Services 600 Crane Church Rd Columbia "The Barbershop" 812111 -Barber Shops 9400 Two Notch Rd Columbia "The Handy Duck", LLC 236118-B -Residential Remodelers 9519 Farrow Rd Columbia #1 A LifeSafer of South Carolina, Inc LifeSafer 811198 -All Other Automotive Repair and Maintenance 136 McLeod Rd Columbia #1 Lawn Care Service 561730 -Landscaping Services 966 Farnsworth Dr Hopkins #MrGrindOut LLC 624110 -Child and Youth Services 536 Wilkinson Ln Columbia 1 800 Got Junk 562111 -Solid Waste Collection 3405 Margrave Rd Columbia 1 Man Outfit & Helpers 236118-B -Residential Remodelers 324 Cooper Rd Blythewood 100 Gateway SC 531120 -Lessors of Nonresidential Buildings (except Miniwarehouses)100 Gateway Corporate Blvd Columbia 1009 Pine, LLC Sun Massage Therapy 621399 -Offices -

The Voices Oftoni Morrison

The Voices ofToni Morrison The Voices of Tom Morrison Barbara Hill Rigney Ohio State University Press Columbus Copyright © 1991 by the Ohio State University Press. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rigney, Barbara Hill, 1938 The voices of Toni Morrison / Barbara Hill Rigney. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8142-0555-0 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Morrison, Toni—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Feminism and literature—United States—History—20th century. 3. Afro-American women in literature. I. Title. PS3563.08749Z84 1991 813'.54—dc20 91-16092 CIP Text design by Hunter Graphics. Cover design by Donna Hartwick. Cover illustration: Aminah Robinson, "Woman Resting," Sapelo Island Series, 1985. Collection of the artist. Courtesy of Esther Saks Gallery. Type set in ITC Galliard by G8cS Typesetters, Austin, TX. Printed by Bookcrafters, Chelsea, MI. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Printed in the U.S.A. 98765432 For Kim, Julie, Kris, Sky, and Papa I gratefully acknowledge the time and the encouragement pro vided by the College of Humanities and the Department of En glish at The Ohio State University, the support of my editor, Charlotte Dihoff, and the invaluable assistance and advice of both colleagues and students, most particularly Murray Beja, Erika Bourguignon, Grace Epstein, Michael Hitt, Sebastian Knowles, Marlene Longenecker, and James Phelan. Contents Introduction 1 1 Breaking the Back of Words: Language and Signification 7 2 Hagar's Mirror: Self and Identity 35 3 "The Disremembered and Unaccounted For": History, Myth, and Magic 61 4 Rainbows and Brown Sugar: Desire and the Erotic 83 Afterword 105 Notes 109 Bibliography 115 Index 125 Introduction . -

Competition Program!

StarQuest Performing Arts Competition RoyRoy Wilkins Wilkins Auditorium Auditorium @ Saint @ SaintPaul River Paul Centre Rive Saint Paul, MN, MN 14. Gold [Classic] Monday, May 3, 2021 Francesca Krejci 15. Silent Night [Classic] Bria Weaver Jazz Doors Open - Yackel Dance Studio Age 10 16. Material Girl [Classic] 3:00 PM Mary Wolsfeld Lyrical Age 10 Yackel Dance Studio Competition 17. Pure Imagination [Classic] Reagan Cracauer 3:25 PM Tap Petite Solo Age 11 18. Diamonds [Classic] Jazz Chloe Steenberg Age 6 Lyrical 1. Downtown [Classic] Age 9 Molly Callahan 19. She's Like The Swallow Age 7 Lauren Callahan 2. Lip Gloss [Classic] Age 11 Skyla Buggs 20. Tightrope 3. I'm Going Bananas [Classic] Sadie Pogatchnik Grace Wasley Open Lyrical Age 9-11 Age 7 21. Light 4. Colors Of The Wind [Classic] Penelope Wiken Elliot Lauenstein Lyrical Age 8 5. You Are My Sunshine [Classic] Age 11 Elidy Chaffee 22. Wonderful World 6. The Face [Classic] Mallory Heuer Sawyer Cracauer 23. Breathe Evelyn Miles Junior Duet/Trio Open Petite Duet/Trio Jazz Age 9-11 7. Out Age 7 Mallory Heuer, Sadie Pogatchnik, Penelope Wiken 24. Dive In The Pool [Classic] Lyrical Elidy Chaffee, Elliot Lauenstein, Fynn Swanson Age 8 Age 10 25. Hound Dog 8. Daylight Lauren Callahan, Sawyer Cracauer Ali Jorgenson, Keira Jorgenson Junior Solo Senior Duet/Trio Lyrical Open Age 16 Age 9-11 25.5. Someone To Stay 9. Suspicion [Classic] Gabrielle Fabio, Grace Fabio Arianna Munoz 10. Heart Cry [Classic] Teen Solo Mya Peterson Open 11. Rare Bird [Classic] Age 12-14 Aubrey Walker 26. -

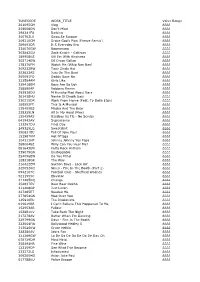

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When