No Evidence for Phonology First 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Janet and John: Here We Go Free Download

JANET AND JOHN: HERE WE GO FREE DOWNLOAD Mabel O'Donnell,Rona Munro | 40 pages | 03 Sep 2007 | Summersdale Publishers | 9781840246131 | English | Chichester, United Kingdom Janet and John Series Toral Taank rated it it was amazing Nov 29, All of our paper waste is recycled and turned into corrugated cardboard. Doesn't post to Germany See details. Visit my eBay shop. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Shelves: beginner-readersfemale-author-or- illustrator. Hardcover40 pages. Reminiscing Read these as a child, Janet and John: Here We Go use with my Grandbabies X Previous image. Books by Mabel O'Donnell. No doubt, Janet and John: Here We Go critics will carp at the daringly minimalist plot and character de In a recent threadsome people stated their objections to literature which fails in its duty to be gender-balanced. Please enter a number less than or equal to Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Watch this item Unwatch. Novels portal Children's literature portal. Janet and John: Here We Go O'Donnell and Rona Munro. Ronne Randall. Learning to read. Inas part of a trend in publishing nostalgic facsimiles of old favourites, Summersdale Publishers reissued two of the original Janet and John books, Here We Go and Off to Play. Analytical phonics Basal reader Guided reading Independent reading Literature circle Phonics Reciprocal teaching Structured word inquiry Synthetic phonics Whole language. We offer great value books on a wide range of subjects and we have grown steadily to become one of the UK's leading retailers of second-hand books. -

Laryngeal Features in German* Michael Jessen Bundeskriminalamt, Wiesbaden Catherine Ringen University of Iowa

Phonology 19 (2002) 189–218. f 2002 Cambridge University Press DOI: 10.1017/S0952675702004311 Printed in the United Kingdom Laryngeal features in German* Michael Jessen Bundeskriminalamt, Wiesbaden Catherine Ringen University of Iowa It is well known that initially and when preceded by a word that ends with a voiceless sound, German so-called ‘voiced’ stops are usually voiceless, that intervocalically both voiced and voiceless stops occur and that syllable-final (obstruent) stops are voiceless. Such a distribution is consistent with an analysis in which the contrast is one of [voice] and syllable-final stops are devoiced. It is also consistent with the view that in German the contrast is between stops that are [spread glottis] and those that are not. On such a view, the intervocalic voiced stops arise because of passive voicing of the non-[spread glottis] stops. The purpose of this paper is to present experimental results that support the view that German has underlying [spread glottis] stops, not [voice] stops. 1 Introduction In spite of the fact that voiced (obstruent) stops in German (and many other Germanic languages) are markedly different from voiced stops in languages like Spanish, Russian and Hungarian, all of these languages are usually claimed to have stops that contrast in voicing. For example, Wurzel (1970), Rubach (1990), Hall (1993) and Wiese (1996) assume that German has underlying voiced stops in their different accounts of Ger- man syllable-final devoicing in various rule-based frameworks. Similarly, Lombardi (1999) assumes that German has underlying voiced obstruents in her optimality-theoretic (OT) account of syllable-final laryngeal neutralisation and assimilation in obstruent clusters. -

Comparing the Word Processing and Reading Comprehension of Skilled and Less Skilled Readers

Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice - 12(4) • Autumn • 2822-2828 ©2012 Educational Consultancy and Research Center www.edam.com.tr/estp Comparing the Word Processing and Reading Comprehension of Skilled and Less Skilled Readers İ. Birkan GULDENOĞLU Tevhide KARGINa Paul MILLER Ankara University Ankara University University of Haifa Abstract The purpose of this study was to compare the word processing and reading comprehension skilled in and less skilled readers. Forty-nine, 2nd graders (26 skilled and 23 less skilled readers) partici- pated in this study. They were tested with two experiments assessing their processing of isolated real word and pseudoword pairs as well as their reading comprehension skills. Findings suggest that there is a significant difference between skilled and less skilled readers both with regard to their word processing skills and their reading comprehension skills. In addition, findings suggest that word processing skills and reading comprehension skills correlate positively both skilled and less skilled readers. Key Words Reading, Reading Comprehension, Word Processing Skills, Reading Theories. Reading is one of the most central aims of school- According to the above mentioned phonologi- ing and all children are expected to acquire this cal reading theory, readers first recognize written skill in school (Güzel, 1998; Moates, 2000). The words phonologically via their spoken lexicon and, ability to read is assumed to rely on two psycho- subsequently, apply their linguistic (syntactic, se- linguistic processes: -

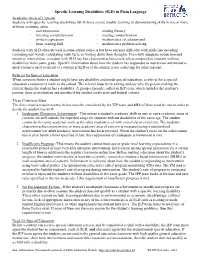

Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) in Plain Language

Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) in Plain Language Academic Areas of Concern Students with specific learning disabilities (SLD) have severe trouble learning or demonstrating skills in one or more of these academic areas: oral expression reading fluency listening comprehension reading comprehension written expression mathematics calculation and basic reading skill mathematics problem solving Students with SLD often do well in some school subjects but have extreme difficulty with skills like decoding (sounding out) words, calculating math facts, or writing down their thoughts. Even with adequate instruction and intensive intervention, a student with SLD has low classroom achievement when compared to students without disabilities in the same grade. Specific information about how the student has responded to instruction and intensive intervention is used to decide if a student is SLD or if the student is not achieving for other reasons. Referral for Special Education When someone thinks a student might have any disability and needs special education, a referral for a special education evaluation is made to the school. The referral must be in writing and say why the person making the referral thinks the student has a disability. A group of people, called an IEP team, which includes the student’s parents, does an evaluation and decides if the student meets state and federal criteria. Three Criteria to Meet The three criteria (requirements) below must be considered by the IEP team and all 3 of them must be met in order to decide the student has SLD. 1. Inadequate Classroom Achievement - This means a student's academic skills in one or more academic areas of concern are well outside the expected range for students without disabilities of the same age. -

Learning About Phonology and Orthography

EFFECTIVE LITERACY PRACTICES MODULE REFERENCE GUIDE Learning About Phonology and Orthography Module Focus Learning about the relationships between the letters of written language and the sounds of spoken language (often referred to as letter-sound associations, graphophonics, sound- symbol relationships) Definitions phonology: study of speech sounds in a language orthography: study of the system of written language (spelling) continuous text: a complete text or substantive part of a complete text What Children Children need to learn to work out how their spoken language relates to messages in print. Have to Learn They need to learn (Clay, 2002, 2006, p. 112) • to hear sounds buried in words • to visually discriminate the symbols we use in print • to link single symbols and clusters of symbols with the sounds they represent • that there are many exceptions and alternatives in our English system of putting sounds into print Children also begin to work on relationships among things they already know, often long before the teacher attends to those relationships. For example, children discover that • it is more efficient to work with larger chunks • sometimes it is more efficient to work with relationships (like some word or word part I know) • often it is more efficient to use a vague sense of a rule How Children Writing Learn About • Building a known writing vocabulary Phonology and • Analyzing words by hearing and recording sounds in words Orthography • Using known words and word parts to solve new unknown words • Noticing and learning about exceptions in English orthography Reading • Building a known reading vocabulary • Using known words and word parts to get to unknown words • Taking words apart while reading Manipulating Words and Word Parts • Using magnetic letters to manipulate and explore words and word parts Key Points Through reading and writing continuous text, children learn about sound-symbol relation- for Teachers ships, they take on known reading and writing vocabularies, and they can use what they know about words to generate new learning. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

Reading Comprehension Difficulties Handout for Students

Reading Comprehension Difficulties Definition: Reading comprehension is a process in which knowledge of language, knowledge of the world, and knowledge of a topic interact to make complex meaning. It involves decoding, word association, context association, summary, analogy, integration, and critique. The Symptoms: Students who have difficulty with reading comprehension may have trouble identifying and understanding important ideas in reading passages, may have trouble with basic reading skills such as word recognition, may not remember what they’ve read, and may frequently avoid reading due to frustration. How to improve your reading comprehension: It is important to note that this is not just an English issue—all school subjects require reading comprehension. The following techniques can help to improve your comprehension: Take a look at subheadings and any editor’s introduction before you begin reading so that you can predict what the reading will be about. Ask yourself what you know about a subject before you begin reading to activate prior knowledge. Ask questions about the text as you read—this engages your brain. Take notes as you read, either in the book or on separate paper: make note of questions you may have, interesting ideas, and important concepts, anything that strikes your fancy. This engages your brain as you read and gives you something to look back on so that you remember what to discuss with your instructor and/or classmates or possibly use in your work for the class. Make note of how texts in the subject area are structured you know how and where to look for different types of information. -

Traditional Chinese Phonology Guillaume Jacques Chinese Historical Phonology Differs from Most Domains of Contemporary Linguisti

Traditional Chinese Phonology Guillaume Jacques Chinese historical phonology differs from most domains of contemporary linguistics in that its general framework is based in large part on a genuinely native tradition. The non-Western outlook of the terminology and concepts used in Chinese historical phonology make this field extremely difficult to understand for both experts in other fields of Chinese linguistics and historical phonologists specializing in other language families. The framework of Chinese phonology derives from the tradition of rhyme books and rhyme tables, which dates back to the medieval period (see section 1 and 2, as well as the corresponding entries). It is generally accepted that these sources were not originally intended as linguistic descriptions of the spoken language; their main purpose was to provide standard character readings for literary Chinese (see subsection 2.4). Nevertheless, these documents also provide a full-fledged terminology describing both syllable structure (initial consonant, rhyme, tone) and several phonological features (places of articulation of consonants and various features that are not always trivial to interpret, see section 2) of the Chinese language of their time (on the problematic concept of “Middle Chinese”, see the corresponding entry). The terminology used in this field is by no means a historical curiosity only relevant to the history of linguistics. It is still widely used in contemporary Chinese phonology, both in works concerning the reconstruction of medieval Chinese and in the description of dialects (see for instance Ma and Zhang 2004). In this framework, the phonological information contained in the medieval documents is used to reconstruct the pronunciation of earlier stages of Chinese, and the abstract categories of the rhyme tables (such as the vexing děng 等 ‘division’ category) receive various phonetic interpretations. -

A LOOK at MISSION STATEMENTS of SELECTED ASIAN COMPANIES Purpose Mission Statements Are Important Corporate Communication Tool for Organizations

Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan Volume No. 54, Issue No. 2 (July - December, 2017) Muhammad Khalid Khan * Ghulam Ali Bhatti** Ishfaq Ahmed*** Talat Islam **** READABILITY AND UNDERSTANDABILITY: A LOOK AT MISSION STATEMENTS OF SELECTED ASIAN COMPANIES Purpose Mission statements are important corporate communication tool for organizations. In order to be purposeful it should be comprehendible and easy to understand. Considering the importance of mission statements readability, this research endeavor is aimed to judge the level of readability and understandability of mission statements of Asian companies listed in Fortune 500 for the year of 2015. Design/Methodology Asian companies listed in Global Fortune-500 for 2014-2015 were taken. There were 197 Asian companies present in that listing. In order to fetch mission statements of those companies their websites were visited from Feb, 2016-April 2016. Mission statements were analyzed for their readability and understandability by estimating total sentences, total words and number of words per sentence (simple counting technique) and following tests: automated readability index, Coleman Liau index, Flasch Reading Ease tests and Gunning fog index. Findings It is evident from the study that mission statements of Asian companies are long and difficult to read and understand. Trading sector is found to have shortest mission statement, with ease of reading and understandability, when compared to other sectors. Research Limitations/Future Directions Future researchers should use other sophisticated evaluation tools and the analysis should also include the influence of country culture on contents and traits of mission statements. * Dr. Muhammad Khalid Khan, Assistant Professor, Registrar & Director HR, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan, [email protected]. -

Effective Vocabulary Instruction by Joan Sedita

Published in “Insights on Learning Disabilities” 2(1) 33-45, 2005 Effective Vocabulary Instruction By Joan Sedita Why is vocabulary instruction important? Vocabulary is one of five core components of reading instruction that are essential to successfully teach children how to read. These core components include phonemic awareness, phonics and word study, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension (National Reading Panel, 2000). Vocabulary knowledge is important because it encompasses all the words we must know to access our background knowledge, express our ideas and communicate effectively, and learn about new concepts. “Vocabulary is the glue that holds stories, ideas and content together… making comprehension accessible for children.” (Rupley, Logan & Nichols, 1998/99). Students’ word knowledge is linked strongly to academic success because students who have large vocabularies can understand new ideas and concepts more quickly than students with limited vocabularies. The high correlation in the research literature of word knowledge with reading comprehension indicates that if students do not adequately and steadily grow their vocabulary knowledge, reading comprehension will be affected (Chall & Jacobs, 2003). There is a tremendous need for more vocabulary instruction at all grade levels by all teachers. The number of words that students need to learn is exceedingly large; on average students should add 2,000 to 3,000 new words a year to their reading vocabularies (Beck, McKeown & Kucan, 2002). For some categories of students, there are significant obstacles to developing sufficient vocabulary to be successful in school: • Students with limited or no knowledge of English. Literate English (English used in textbooks and printed material) is different from spoken or conversational English. -

Is Vocabulary a Strong Variable Predicting Reading Comprehension and Does the Prediction Degree of Vocabulary Vary According to Text Types

Kuram ve Uygulamada Eğitim Bilimleri • Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice - 11(3) • Summer • 1541-1547 ©2011 Eğitim Danışmanlığı ve Araştırmaları İletişim Hizmetleri Tic. Ltd. Şti. Is Vocabulary a Strong Variable Predicting Reading Comprehension and Does the Prediction Degree of Vocabulary Vary according to Text Types Kasım YILDIRIMa Mustafa YILDIZ Seyit ATEŞ Ahi Evran University Gazi University Gazi University Abstract The purpose of this study was to explore whether there was a significant correlation between vocabulary and re- ading comprehension in terms of text types as well as whether the vocabulary was a predictor of reading comp- rehension in terms of text types. In this regard, the correlational research design was used to explain specific research objectives. The study was conducted in Ankara-Sincan during the 2008-2009 academic years. A total of 120 students having middle socioeconomic status participated in this study. The students in this research were in the fifth-grade at a public school. Reading comprehension and vocabulary tests were developed to evaluate the students’ reading comprehension and vocabulary levels. Correlation and bivariate linear regression analy- ses were used to assess the data obtained from the study. The research findings indicated that there was a me- dium correlation between vocabulary and narrative text comprehension. In addition, there was a large correlati- on between vocabulary and expository text comprehension. Compared to the narrative text comprehension, vo- cabulary was also a strong predictor of expository text comprehension. Vocabulary made more contribution to expository text comprehension than narrative text comprehension. Key Words Vocabulary, Reading Comprehension, Text Types. Reading comprehension is defined as a complex Reader factor includes prior knowledge, linguistic process in which many skills are used (Cain, Oa- skill, and metacognitive awareness. -

Research and the Reading Wars James S

CHAPTER 4 Research and the Reading Wars James S. Kim Controversy over the role of phonics in reading instruction has persisted for over 100 years, making the reading wars seem like an inevitable fact of American history. In the mid-nineteenth century, Horace Mann, the secre- tary of the Massachusetts Board of Education, railed against the teaching of the alphabetic code—the idea that letters represented sounds—as an imped- iment to reading for meaning. Mann excoriated the letters of the alphabet as “bloodless, ghostly apparitions,” and argued that children should first learn to read whole words) The 1886 publication of James Cattell’s pioneer- ing eye movement study showed that adults perceived words more rapidly 2 than letters, providing an ostensibly scientific basis for Mann’s assertions. In the twentieth century, state education officials like Mann have contin- ued to voice strong opinions about reading policy and practice, aiding the rapid implementation of whole language—inspired curriculum frameworks and texts during the late 1980s. And scientists like Cattell have shed light on theprocesses underlying skillful reading, contributing to a growing scientific 3 consensus that culminated in the 2000 National Reading Panel report. This chapter traces the history of the reading wars in both the political arena and the scientific community. The narrative is organized into three sections. The first offers the history of reading research in the 1950s, when the “conventional wisdom” in reading was established by acclaimed lead- ers in the field like William Gray, who encouraged teachers to instruct chil- dren how to read whole words while avoiding isolated phonics drills.