11. Kinematics of Angular Motion Rk.Nb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 141. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/141 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 11 Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) 11-1 Motion about a Fixed Axis The motion of the flywheel of an engine and of a pulley on its axle are examples of an important type of motion of a rigid body, that of the motion of rotation about a fixed axis. Consider the motion of a uniform disk rotat ing about a fixed axis passing through its center of gravity C perpendicular to the face of the disk, as shown in Figure 11-1. The motion of this disk may be de scribed in terms of the motions of each of its individual particles, but a better way to describe the motion is in terms of the angle through which the disk rotates. -

M1=100 Kg Adult, M2=10 Kg Baby. the Seesaw Starts from Rest. Which Direction Will It Rotates?

m1 m2 m1=100 kg adult, m2=10 kg baby. The seesaw starts from rest. Which direction will it rotates? (a) Counter-Clockwise (b) Clockwise ()(c) NttiNo rotation (d) Not enough information Effect of a Constant Net Torque 2.3 A constant non-zero net torque is exerted on a wheel. Which of the following quantities must be changing? 1. angular position 2. angular velocity 3. angular acceleration 4. moment of inertia 5. kinetic energy 6. the mass center location A. 1, 2, 3 B. 4, 5, 6 C. 1,2, 5 D. 1, 2, 3, 4 E. 2, 3, 5 1 Example: second law for rotation PP10601-50: A torque of 32.0 N·m on a certain wheel causes an angular acceleration of 25.0 rad/s2. What is the wheel's rotational inertia? Second Law example: α for an unbalanced bar Bar is massless and originally horizontal Rotation axis at fulcrum point L1 N L2 Î N has zero torque +y Find angular acceleration of bar and the linear m1gmfulcrum 2g acceleration of m1 just after you let go τnet Constraints: Use: τnet = Itotα ⇒ α = Itot 2 2 Using specific numbers: where: Itot = I1 + I2 = m1L1 + m2L2 Let m1 = m2= m L =20 cm, L = 80 cm τnet = ∑ τo,i = + m1gL1 − m2gL2 1 2 θ gL1 − gL2 g(0.2 - 0.8) What happened to sin( ) in moment arm? α = 2 2 = 2 2 L1 + L2 0.2 + 0.8 2 net = − 8.65 rad/s Clockwise torque m gL − m gL a ==+ -α L 1.7 m/s2 α = 1 1 2 2 11 2 2 Accelerates UP m1L1 + m2L2 total I about pivot What if bar is not horizontal? 2 See Saw 3.1. -

Kinematics Study of Motion

Kinematics Study of motion Kinematics is the branch of physics that describes the motion of objects, but it is not interested in its causes. Itziar Izurieta (2018 october) Index: 1. What is motion? ............................................................................................ 1 1.1. Relativity of motion ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2.Frame of reference: Cartesian coordinate system ....................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3. Position and trajectory .......................................................................................................................... 2 1.4.Travelled distance and displacement ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Quantities of motion: Speed and velocity .............................................. 4 2.1. Average and instantaneous speed ............................................................ 4 2.2. Average and instantaneous velocity ........................................................ 7 3. Uniform linear motion ................................................................................. 9 3.1. Distance-time graph .................................................................................. 10 3.2. Velocity-time -

PHYSICS of ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY Angie Bukley1, William Paloski,2 and Gilles Clément1,3

Chapter 2 PHYSICS OF ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY Angie Bukley1, William Paloski,2 and Gilles Clément1,3 1 Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, USA 2 NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas, USA 3 Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Toulouse, France This chapter discusses potential technologies for achieving artificial gravity in a space vehicle. We begin with a series of definitions and a general description of the rotational dynamics behind the forces ultimately exerted on the human body during centrifugation, such as gravity level, gravity gradient, and Coriolis force. Human factors considerations and comfort limits associated with a rotating environment are then discussed. Finally, engineering options for designing space vehicles with artificial gravity are presented. Figure 2-01. Artist's concept of one of NASA early (1962) concepts for a manned space station with artificial gravity: a self- inflating 22-m-diameter rotating hexagon. Photo courtesy of NASA. 1 ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY: WHAT IS IT? 1.1 Definition Artificial gravity is defined in this book as the simulation of gravitational forces aboard a space vehicle in free fall (in orbit) or in transit to another planet. Throughout this book, the term artificial gravity is reserved for a spinning spacecraft or a centrifuge within the spacecraft such that a gravity-like force results. One should understand that artificial gravity is not gravity at all. Rather, it is an inertial force that is indistinguishable from normal gravity experience on Earth in terms of its action on any mass. A centrifugal force proportional to the mass that is being accelerated centripetally in a rotating device is experienced rather than a gravitational pull. -

Introduction to Robotics Lecture Note 5: Velocity of a Rigid Body

ECE5463: Introduction to Robotics Lecture Note 5: Velocity of a Rigid Body Prof. Wei Zhang Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Ohio State University Columbus, Ohio, USA Spring 2018 Lecture 5 (ECE5463 Sp18) Wei Zhang(OSU) 1 / 24 Outline Introduction • Rotational Velocity • Change of Reference Frame for Twist (Adjoint Map) • Rigid Body Velocity • Outline Lecture 5 (ECE5463 Sp18) Wei Zhang(OSU) 2 / 24 Introduction For a moving particle with coordinate p(t) 3 at time t, its (linear) velocity • R is simply p_(t) 2 A moving rigid body consists of infinitely many particles, all of which may • have different velocities. What is the velocity of the rigid body? Let T (t) represent the configuration of a moving rigid body at time t.A • point p on the rigid body with (homogeneous) coordinate p~b(t) and p~s(t) in body and space frames: p~ (t) p~ ; p~ (t) = T (t)~p b ≡ b s b Introduction Lecture 5 (ECE5463 Sp18) Wei Zhang(OSU) 3 / 24 Introduction Velocity of p is d p~ (t) = T_ (t)p • dt s b T_ (t) is not a good representation of the velocity of rigid body • - There can be 12 nonzero entries for T_ . - May change over time even when the body is under a constant velocity motion (constant rotation + constant linear motion) Our goal is to find effective ways to represent the rigid body velocity. • Introduction Lecture 5 (ECE5463 Sp18) Wei Zhang(OSU) 4 / 24 Outline Introduction • Rotational Velocity • Change of Reference Frame for Twist (Adjoint Map) • Rigid Body Velocity • Rotational Velocity Lecture 5 (ECE5463 Sp18) Wei Zhang(OSU) 5 / 24 Illustrating -

Centripetal Force Is Balanced by the Circular Motion of the Elctron Causing the Centrifugal Force

STANDARD SC1 b. Construct an argument to support the claim that the proton (and not the neutron or electron) defines the element’s identity. c. Construct an explanation based on scientific evidence of the production of elements heavier than hydrogen by nuclear fusion. d. Construct an explanation that relates the relative abundance of isotopes of a particular element to the atomic mass of the element. First, we quickly review pre-requisite concepts One of the most curious observations with atoms is the fact that there are charged particles inside the atom and there is also constant spinning and Warm-up 1: List the name, charge, mass, and location of the three subatomic circling. How does atom remain stable under these conditions? Remember particles Opposite charges attract each other; Like charges repel each other. Your Particle Location Charge Mass in a.m.u. Task: Read the following information and consult with your teacher as STABILITY OF ATOMS needed, answer Warm-Up tasks 2 and 3 on Page 2. (3) Death spiral does not occur at all! This is because the centripetal force is balanced by the circular motion of the elctron causing the centrifugal force. The centrifugal force is the outward force from the center to the circumference of the circle. Electrons not only spin on their own axis, they are also in a constant circular motion around the nucleus. Despite this terrific movement, electrons are very stable. The stability of electrons mainly comes from the electrostatic forces of attraction between the nucleus and the electrons. The electrostatic forces are also known as Coulombic Forces of Attraction. -

Linear and Angular Velocity Examples

Linear and Angular Velocity Examples Example 1 Determine the angular displacement in radians of 6.5 revolutions. Round to the nearest tenth. Each revolution equals 2 radians. For 6.5 revolutions, the number of radians is 6.5 2 or 13 . 13 radians equals about 40.8 radians. Example 2 Determine the angular velocity if 4.8 revolutions are completed in 4 seconds. Round to the nearest tenth. The angular displacement is 4.8 2 or 9.6 radians. = t 9.6 = = 9.6 , t = 4 4 7.539822369 Use a calculator. The angular velocity is about 7.5 radians per second. Example 3 AMUSEMENT PARK Jack climbs on a horse that is 12 feet from the center of a merry-go-round. 1 The merry-go-round makes 3 rotations per minute. Determine Jack’s angular velocity in radians 4 per second. Round to the nearest hundredth. 1 The merry-go-round makes 3 or 3.25 revolutions per minute. Convert revolutions per minute to radians 4 per second. 3.25 revolutions 1 minute 2 radians 0.3403392041 radian per second 1 minute 60 seconds 1 revolution Jack has an angular velocity of about 0.34 radian per second. Example 4 Determine the linear velocity of a point rotating at an angular velocity of 12 radians per second at a distance of 8 centimeters from the center of the rotating object. Round to the nearest tenth. v = r v = (8)(12 ) r = 8, = 12 v 301.5928947 Use a calculator. The linear velocity is about 301.6 centimeters per second. -

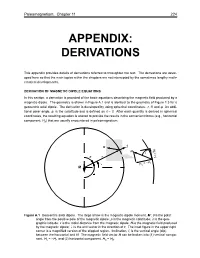

Appendix: Derivations

Paleomagnetism: Chapter 11 224 APPENDIX: DERIVATIONS This appendix provides details of derivations referred to throughout the text. The derivations are devel- oped here so that the main topics within the chapters are not interrupted by the sometimes lengthy math- ematical developments. DERIVATION OF MAGNETIC DIPOLE EQUATIONS In this section, a derivation is provided of the basic equations describing the magnetic field produced by a magnetic dipole. The geometry is shown in Figure A.1 and is identical to the geometry of Figure 1.3 for a geocentric axial dipole. The derivation is developed by using spherical coordinates: r, θ, and φ. An addi- tional polar angle, p, is the colatitude and is defined as π – θ. After each quantity is derived in spherical coordinates, the resulting equation is altered to provide the results in the convenient forms (e.g., horizontal component, Hh) that are usually encountered in paleomagnetism. H ^r H H h I = H p r = –Hr H v M Figure A.1 Geocentric axial dipole. The large arrow is the magnetic dipole moment, M ; θ is the polar angle from the positive pole of the magnetic dipole; p is the magnetic colatitude; λ is the geo- graphic latitude; r is the radial distance from the magnetic dipole; H is the magnetic field produced by the magnetic dipole; rˆ is the unit vector in the direction of r. The inset figure in the upper right corner is a magnified version of the stippled region. Inclination, I, is the vertical angle (dip) between the horizontal and H. The magnetic field vector H can be broken into (1) vertical compo- nent, Hv =–Hr, and (2) horizontal component, Hh = Hθ . -

Measuring Inertial, Centrifugal, and Centripetal Forces and Motions The

Measuring Inertial, Centrifugal, and Centripetal Forces and Motions Many people are quite confused about the true nature and dynamics of cen- trifugal and centripetal forces. Some believe that centrifugal force is a fictitious radial force that can’t be measured. Others claim it is a real force equal and opposite to measured centripetal force. It is sometimes thought to be a continu- ous positive acceleration like centripetal force. Crackpot theorists ignore all measurements and claim the centrifugal force comes out of the aether or spa- cetime continuum surrounding a spinning body. The true reality of centripetal and centrifugal forces can be easily determined by simply measuring them with accelerometers rather than by imagining metaphysical assumptions. The Momentum and Energy of the Cannon versus a Cannonball Cannon Ball vs Cannon Momentum and Energy Force = mass x acceleration ma = Momentum = mv m = 100 kg m = 1 kg v = p/m = 1 m/s v = p/m = 100 m/s p = mv 100 p = mv = 100 energy = mv2/2 = 50 J energy = mv2/2 = 5,000 J Force p = mv = p = mv p=100 Momentum p = 100 Energy mv2/2 = mv2 = mv2/2 Cannon ball has the same A Force always produces two momentum as the cannon equal momenta but it almost but has 100 times more never produces two equal kinetic energy. quantities of kinetic energy. In the following thought experiment with a cannon and golden cannon ball, their individual momentum is easy to calculate because they are always equal. However, the recoil energy from the force of the gunpowder is much greater for the ball than the cannon. -

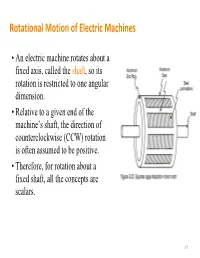

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines • An electric machine rotates about a fixed axis, called the shaft, so its rotation is restricted to one angular dimension. • Relative to a given end of the machine’s shaft, the direction of counterclockwise (CCW) rotation is often assumed to be positive. • Therefore, for rotation about a fixed shaft, all the concepts are scalars. 17 Angular Position, Velocity and Acceleration • Angular position – The angle at which an object is oriented, measured from some arbitrary reference point – Unit: rad or deg – Analogy of the linear concept • Angular acceleration =d/dt of distance along a line. – The rate of change in angular • Angular velocity =d/dt velocity with respect to time – The rate of change in angular – Unit: rad/s2 position with respect to time • and >0 if the rotation is CCW – Unit: rad/s or r/min (revolutions • >0 if the absolute angular per minute or rpm for short) velocity is increasing in the CCW – Analogy of the concept of direction or decreasing in the velocity on a straight line. CW direction 18 Moment of Inertia (or Inertia) • Inertia depends on the mass and shape of the object (unit: kgm2) • A complex shape can be broken up into 2 or more of simple shapes Definition Two useful formulas mL2 m J J() RRRR22 12 3 1212 m 22 JRR()12 2 19 Torque and Change in Speed • Torque is equal to the product of the force and the perpendicular distance between the axis of rotation and the point of application of the force. T=Fr (Nm) T=0 T T=Fr • Newton’s Law of Rotation: Describes the relationship between the total torque applied to an object and its resulting angular acceleration. -

Unit 1: Motion

Macomb Intermediate School District High School Science Power Standards Document Physics The Michigan High School Science Content Expectations establish what every student is expected to know and be able to do by the end of high school. They also outline the parameters for receiving high school credit as dictated by state law. To aid teachers and administrators in meeting these expectations the Macomb ISD has undertaken the task of identifying those content expectations which can be considered power standards. The critical characteristics1 for selecting a power standard are: • Endurance – knowledge and skills of value beyond a single test date. • Leverage - knowledge and skills that will be of value in multiple disciplines. • Readiness - knowledge and skills necessary for the next level of learning. The selection of power standards is not intended to relieve teachers of the responsibility for teaching all content expectations. Rather, it gives the school district a common focus and acts as a safety net of standards that all students must learn prior to leaving their current level. The following document utilizes the unit design including the big ideas and real world contexts, as developed in the science companion documents for the Michigan High School Science Content Expectations. 1 Dr. Douglas Reeves, Center for Performance Assessment Unit 1: Motion Big Ideas The motion of an object may be described using a) motion diagrams, b) data, c) graphs, and d) mathematical functions. Conceptual Understandings A comparison can be made of the motion of a person attempting to walk at a constant velocity down a sidewalk to the motion of a person attempting to walk in a straight line with a constant acceleration. -

Physics B Topics Overview ∑

Physics 106 Lecture 1 Introduction to Rotation SJ 7th Ed.: Chap. 10.1 to 3 • Course Introduction • Course Rules & Assignment • TiTopics Overv iew • Rotation (rigid body) versus translation (point particle) • Rotation concepts and variables • Rotational kinematic quantities Angular position and displacement Angular velocity & acceleration • Rotation kinematics formulas for constant angular acceleration • Analogy with linear kinematics 1 Physics B Topics Overview PHYSICS A motion of point bodies COVERED: kinematics - translation dynamics ∑Fext = ma conservation laws: energy & momentum motion of “Rigid Bodies” (extended, finite size) PHYSICS B rotation + translation, more complex motions possible COVERS: rigid bodies: fixed size & shape, orientation matters kinematics of rotation dynamics ∑Fext = macm and ∑ Τext = Iα rotational modifications to energy conservation conservation laws: energy & angular momentum TOPICS: 3 weeks: rotation: ▪ angular versions of kinematics & second law ▪ angular momentum ▪ equilibrium 2 weeks: gravitation, oscillations, fluids 1 Angular variables: language for describing rotation Measure angles in radians simple rotation formulas Definition: 360o 180o • 2π radians = full circle 1 radian = = = 57.3o • 1 radian = angle that cuts off arc length s = radius r 2π π s arc length ≡ s = r θ (in radians) θ ≡ rad r r s θ’ θ Example: r = 10 cm, θ = 100 radians Æ s = 1000 cm = 10 m. Rigid body rotation: angular displacement and arc length Angular displacement is the angle an object (rigid body) rotates through during some time interval..... ...also the angle that a reference line fixed in a body sweeps out A rigid body rotates about some rotation axis – a line located somewhere in or near it, pointing in some y direction in space • One polar coordinate θ specifies position of the whole body about this rotation axis.