84603977.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exors and the Stellar Birthline Mackenzie S

A&A 600, A133 (2017) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201630196 & c ESO 2017 Astrophysics EXors and the stellar birthline Mackenzie S. L. Moody1 and Steven W. Stahler2 1 Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA e-mail: [email protected] 2 Astronomy Department, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA e-mail: [email protected] Received 6 December 2016 / Accepted 23 February 2017 ABSTRACT We assess the evolutionary status of EXors. These low-mass, pre-main-sequence stars repeatedly undergo sharp luminosity increases, each a year or so in duration. We place into the HR diagram all EXors that have documented quiescent luminosities and effective temperatures, and thus determine their masses and ages. Two alternate sets of pre-main-sequence tracks are used, and yield similar results. Roughly half of EXors are embedded objects, i.e., they appear observationally as Class I or flat-spectrum infrared sources. We find that these are relatively young and are located close to the stellar birthline in the HR diagram. Optically visible EXors, on the other hand, are situated well below the birthline. They have ages of several Myr, typical of classical T Tauri stars. Judging from the limited data at hand, we find no evidence that binarity companions trigger EXor eruptions; this issue merits further investigation. We draw several general conclusions. First, repetitive luminosity outbursts do not occur in all pre-main-sequence stars, and are not in themselves a sign of extreme youth. They persist, along with other signs of activity, in a relatively small subset of these objects. -

Stellar Rotation in Young Clusters: the First 4 Million Years L

The Astronomical Journal, 127:1029–1051, 2004 February A # 2004. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. STELLAR ROTATION IN YOUNG CLUSTERS: THE FIRST 4 MILLION YEARS L. M. Rebull,1,2 S. C. Wolff,3 and S. E. Strom3 Received 2003 June 3; accepted 2003 October 16 ABSTRACT To investigate what happens to angular momentum during the earliest observable phases of stellar evolution, we searched the literature for periods (P), projected rotational velocities (v sin i), and supporting data on K5–M2 stars (corresponding to masses 0.25–1 M ) from the Orion Nebula Cluster and environs, Ophiuchi, TW Hydra, Taurus-Auriga, NGC 2264, Chamaeleon, Lupus, and Chamaeleonis. We combine these measures of rotation with the stellar R (as determined from Lbol and Teff) to compare the data with two extreme cases: conservation of stellar angular velocity and conservation of stellar angular momentum. Analysis of the P data set suggests that the frequency distribution of periods among the youngest and oldest stars in the sample is indistinguishable, while the v sin i data set reveals a decrease in mean v sin i as a function of age. Both results suggest that a significant fraction of all pre–main-sequence (PMS) stars must evolve at nearly constant angular velocity during the first 3–5 Myr after they begin their evolution down the convective tracks. Hence, the angular momenta of a significant fraction of pre–main-sequence (PMS) stars must be tightly regulated during the first few million years after they first become observable. This result seems surprising at first glance, because observations of young main-sequence stars reveal a population (30%–40%) of rapidly rotating stars that must begin to spin up at ages tT5 Myr. -

Pre-Main-Sequence Star

Pre-main-sequence star A pre-main-sequence star (also known as a PMS star and PMS object) is a star in the stage when it has not yet reached the main sequence. Earlier in its life, the object is a protostar that grows by acquiring mass from its surrounding envelope of interstellar dust and gas. After the protostar blows away this envelope, it is optically visible, and appears on the stellar birthline in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. At this point, the star has acquired nearly all of its mass but has not yet started hydrogen burning (i.e. nuclear fusion of hydrogen). The star then contracts, its internal temperature rising until it begins hydrogen burning on the zero age main sequence. This period of contraction is the pre-main sequence stage.[1][2][3][4] An observed PMS object can either be a T Tauri star, if it has fewer than 2 solar masses (M☉), or else a Herbig Ae/Be star, if it has 2 to 8 M☉. Yet more massive stars have no pre-main-sequence stage because they contract too quickly as protostars. By the time they become visible, the hydrogen in their centers is already fusing and they are main-sequence objects. The energy source of PMS objects is gravitational contraction, as opposed to hydrogen burning in main-sequence stars. In the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram, pre-main-sequence stars with more than 0.5 M☉ first move vertically downward along Hayashi tracks, then leftward and horizontally along Henyey tracks, until they finally halt at the main sequence. -

MHD Simulation of Inner 0.5 AU of FU Ori, Zhu Et Al

Star Formation and the Origins of Planetary Systems Lecture 6: Pre-main sequence stars MHD simulation of inner 0.5 AU of FU Ori, Zhu et al. (2020) Background reading: (Crete II) Hartmann (2008) book, Chapters: 4.1-4.2, 8.4-8.8, all of 9, all of 11 !1 Summary Lecture 5 ▪Census of high-mass YSOs in Milky Way now possible due to new observational facilities ▪Spitzer, Herschel, masers, radio ▪Earliest pre-stellar core phase still elusive ▪Two theories for massive star formation ▪Scaled-up version low-mass: turbulent core accretion ▪Competitive accretion ▪Scenario (under debate) ▪IRDC → HMPO→ hot core→UC HII ▪Long lifetime and range of morphologies UC HII regions due to combination of effects ▪No optically visible pre-main sequence phase !2 Summary Image Credit: Cormac Purcell •Hyper-compact HII regions (eg Observed as cold, dense cores Kurtz et al. 2005) •Infrared-dark clouds •Ultra-compact HII regions - well •“mm-only” cores studied (see Churchwell and co.) Q: What is wrong with this picture? A: It has all of these stages separately, whereas in reality one finds observationally a hot core next to an ultra compact H II region. SPF course progress: where are we now? Date Who Lecture 18 Feb. EvD Motivation, history, & observational facilities (Star formation) 20 Feb. EvD Pre-stellar cores, cloud collapse 25 Feb. EvD SEDs, embedded protostars Has links to core courses: 27 Feb. EvD Outflows & jets • ISM • Stellar structure & evolution 3 Mar. EvD High mass star formation 10 Mar. MM Pre-main sequence star types, stellar birthline 12 Mar. -

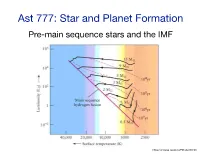

Ast 777: Star and Planet Formation Pre-Main Sequence Stars and the IMF

Ast 777: Star and Planet Formation Pre-main sequence stars and the IMF https://universe-review.ca/F08-star05.htm The main phases of star formation https://www.americanscientist.org/sites/americanscientist.org/files/2005223144527_306.pdf The star has formed* but is not yet on the MS * it has attained its final mass (or ~99% of it) https://www.americanscientist.org/sites/americanscientist.org/files/2005223144527_306.pdf The star is optically visible and is a Class II or III star (or TTS or HAeBe) https://www.americanscientist.org/sites/americanscientist.org/files/2005223144527_306.pdf PMS evolution is described by the equations of stellar evolution But there are differences from MS evolution: ‣ initial conditions are very different from the MS (and have significant uncertainties) ‣ energy is produced by gravitational collapse and deuterium burning (This was mostly figured out 30-50 years ago so the references are old, but important for putting current work in context) But see later… How big is a star when the core stops collapsing? Upper limit can be determined by assuming that all the gravitational energy of the core is used to dissociate and ionized the H2+He gas (i.e., no radiative losses during collapse) Each H2 requires 4.48eV to dissociate —> this produces a short-lived intermediate step along the way to a protostar, called the first hydrostatic core (hinted at, though not definitively confirmed, through FIR/mm observations) How big is a star when the core stops collapsing? Upper limit can be determined by assuming that all the gravitational -

Pre-Main Sequence Star Is Optically Visible, but Has No Central Hydrogen Burning

Definitions • A protostar is the object that forms in the center of a collapsing molecular cloud core, before it finishes the main accretion phase and becomes “optically visible". • A pre-main sequence star is optically visible, but has no central hydrogen burning. • A main sequence star is the result after subsequent contraction and significant increase in central density and temperature, when the star begins to burn hydrogen in its core. Trueism: Gravity always wins • Free-fall time = time for protostellar collapse 1/ 2 $ 3π ' t ff = & ) % 32Gρ( 7 −1/ 2 t ff = 3.4 ×10 n yrs n = 102 cm-3 => free-fall time = 3 x 106 yrs n = 106 cm-3 => free-fall time = 3 x 104 yrs • Too short!! What else can hold up the cloud? € 2 – Magnetic field threading the cloud has pressure Pmag = B /8π 2 – Turbulent velocities in cloud provide pressure Pturb ~ ρvturb Hosokawa Protostellar Infall dM/dt ~ M / tff core is isothermal (n è ∞ polytrope) until it becomes optically thick to own radiation, increasing central temperature. We have ideal gas at this stage, but not yet polytropic. M is increasing with time as object gains mass from infall. van der Tak * van der Tak Recall E = (4-3 γ)U van der Tak Time Scales and Luminosities (as usual, dynamical timescale is the shortest) 5 (few 10 years for 1 Mo) 7 (few 10 years for 1 Mo) (star evolves normally towards the main sequence) = Hosokawa Hosokawa Hosokawa (shock boundary condition) van der Tak van der Tak Hayashi Limit – The Classic Picture Pols Initial Radius – The Classic Picture 3/10 x x 3/10 (R = 36 Rsun at 1 Msun) However, protostellar accretion geometry and accretion history modifies this simple picture. -

Arxiv:Astro-Ph/0508545V1 25 Aug 2005 ZAMS

Massive Star Birth: A Crossroads of Astrophysics Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 227, 2005 c 2005 International Astronomical Union R. Cesaroni, E. Churchwell, M. Felli & M. Walmsley, eds. DOI: 00.0000/X000000000000000X Stellar evolution before the ZAMS Francesco Palla1 1INAF-Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo E. Fermi 5, 50125, Firenze, Italy email: [email protected] Abstract. Young stars on their way to the ZAMS evolve in significantly different ways depending on their mass. While the theoretical and observational properties of low- and intermediate-mass stars are rather well understood and/or empirically tested, the situation for massive stars ( ∼> 10– 15 M⊙) is, to say the least, still elusive. On theoretical grounds, the PMS evolution of these objects should be extremely short, or nonexistent at all. Observationally, despite a great deal of effort, the simple (or bold) predictions of simplified models of massive star formation/evolution have proved more difficult to be checked. After a brief review of the theoretical expectations, I will highlight some critical test on young stars of various masses. Keywords. stars: formation - Hertzsprung-Russell diagram - stars: pre–main-sequence 1. Introduction After a brief, intense, and optically obscured protostellar phase, newly formed stars emerge from their natal environments as relatively bright, distended objects undergo- ing gravitational contraction towards the main sequence. While residual accretion from circumstellar disks is observed to take place in young pre–main-sequence (PMS) stars, the ˙ −7 −1 magnitude of the accretion flow appears to be much lower (typically, MPMS ∼< 10 M⊙ yr ) ˙ −5 −1 than the protostellar one (typically, Mproto ∼< 10 M⊙ yr ). -

Stellar Structure and Evolution: Syllabus 3.3 the Virial Theorem and Its Implications (ZG: P5-2; CO: 2.4) Ph

Page 2 Stellar Structure and Evolution: Syllabus 3.3 The Virial Theorem and its Implications (ZG: P5-2; CO: 2.4) Ph. Podsiadlowski (MT 2006) 3.4 The Energy Equation and Stellar Timescales (CO: 10.3) (DWB 702, (2)73343, [email protected]) (www-astro.physics.ox.ac.uk/˜podsi/lec mm03.html) 3.5 Energy Transport by Radiation (ZG: P5-10, 16-1) and Con- vection (ZG: 16-1; CO: 9.3, 10.4) Primary Textbooks 4. The Equations of Stellar Structure (ZG: 16; CO: 10) ZG: Zeilik & Gregory, “Introductory Astronomy & Astro- • 4.1 The Mathematical Problem (ZG: 16-2; CO: 10.5) physics” (4th edition) 4.1.1 The Vogt-Russell “Theorem” (CO: 10.5) CO: Carroll & Ostlie, “An Introduction to Modern Astro- • 4.1.2 Stellar Evolution physics” (Addison-Wesley) 4.1.3 Convective Regions (ZG: 16-1; CO: 10.4) also: Prialnik, “An Introduction to the Theory of Stellar Struc- • 4.2 The Equation of State ture and Evolution” 4.2.1 Perfect Gas and Radiation Pressure (ZG: 16-1: CO: 1. Observable Properties of Stars (ZG: Chapters 11, 12, 13; CO: 10.2) Chapters 3, 7, 8, 9) 4.2.2 Electron Degeneracy (ZG: 17-1; CO: 15.3) 1.1 Luminosity, Parallax (ZG: 11; CO: 3.1) 4.3 Opacity (ZG: 10-2; CO: 9.2) 1.2 The Magnitude System (ZG: 11; CO: 3.2, 3.6) 5. Nuclear Reactions (ZG: P5-7 to P5-9, P5-12, 16-1D; CO: 10.3) 1.3 Black-Body Temperature (ZG: 8-6; CO: 3.4) 5.1 Nuclear Reaction Rates (ZG: P5-7) 1.4 Spectral Classification, Luminosity Classes (ZG: 13-2/3; CO: 5.2 Hydrogen Burning 5.1, 8.1, 8.3) 5.2.1 The pp Chain (ZG: P5-7, 16-1D) 1.5 Stellar Atmospheres (ZG: 13-1; CO: 9.1, 9.4) 5.2.2 The CN Cycle (ZG: P5-9; 16-1D) 1.6 Stellar Masses (ZG: 12-2/3; CO: 7.2, 7.3) 5.3 Energy Generation from H Burning (CO: 10.3) 1.7 Stellar Radii (ZG: 12-4/5; CO: 7.3) 5.4 Other Reactions Involving Light Elements (Supplementary) 2. -

Tognelli Et Al

Emanuele To g n elli University of Pisa OUTLINE Standard pre-main sequence evolution. The Hayashi track and the ‘simple’ gravitational contraction. (‘60s) Protostellar phase. From gravitational collapse to the formation of the protostellar hydrostatic core. (‘69+’90s+2000s) Main protostellar accretion phase. Spherical and/or disk accretion: the birthline. Connecting pre-main sequence stellar evolution to the protostellar phase. (1) Standard pre-MS evolution Hayashi et al. (1965) 1 – Star formation. (L > 300 Lsun R > 40 Rsun) 1 Msun � ≈ 10.�� 2.5 )* Cold and expanse fully convective 6�/� � ∝ � 1 and hydrostatic structure. 1 3 �)* ≈ 10 − 10 �� 2 �B ≈ 0.1 ��� 2 – Gravitational contraction. No nuclear energy source. The energy radiated comes from the 1.5 2 contraction of the star. D-burning line The energy excess is radiated at 1 log L/Ls � the stellar surface on a Kelvin- = �����. � �B ≈ 1 − 5 ��� Helmholtz timescale 0.5 The contraction produces an 2 increase of the temperature � ≈ 10:�� M 0 )* T ∝ $ R 6 3 D-burning: when T$ reaches 10 K, -0.5 deuterium ignites halting the 3.75 3.7 3.65 3.6 gravitational contraction. log Teff OUTLINE Standard pre-main sequence evolution. The Hayashi track and the ‘simple’ gravitational contraction. (‘60s) Protostellar phase. From gravitational collapse to the formation of the protostellar hydrostatic core. (‘69+’90s+2000s) Main protostellar accretion phase. Spherical and disk accretion: the birthline. Connecting pre-main sequence stellar evolution to the protostellar phase. (1) Protostellar phase The cloud collapse: Larson (1969) (see also Masunaga and Inutsuka 2000) Formation phases. Initial model: cold (~10 K) and low density (~10-19 g cm-3) - Isothermal collapse: because of the low temperture and densities the clouds doesn’t warm up until ρ~106G.g cm6. -

Exors and the Stellar Birthline

Mem. S.A.It. Vol. 88, 616 c SAIt 2017 Memorie della EXors and the stellar birthline S. Stahler Deptartment of Astronomy University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. EXors are young stars whose luminosities periodically increase by up to a factor of 100 within a year. Unlike the better-known FUors, their decay time is also relatively brief, and single objects have been observed to flare multiple times. A popular notion is that EXors rep- resent an especially early phase of pre-main-sequence evolution. Mackenzie Moody and I have shown that classical EXors, those which are visible prior to outburst, have the same age range as classical T Tauri stars. However, embedded EXors, those seen in quiescence at infrared and submillimeter wavelengths, are indeed very young. They lie close to the birthline in the HR di- agram. Photometrically, these objects are typical Class I or flat-spectrum sources. Thus, both categories include stars that are in the pre-main-sequence, and not the true protostellar, phase. An “embedded pre-main-sequence” phase should be included in a more complete description of low-mass stellar evolution. Key words. Stars: pre-main sequence – Stars: variables: general 1. Introduction have been seen to flare multiple times. Thus, the amount of data available to study the phe- One ubiquitous property of young stars is their nomenon is quite extensive. Nevertheless, the variability. The stars which vary in the most current attempts at modeling are even more in- dramatic fashion are the FUors. These objects, conclusive than for FUors, simply because few named for the prototype FU Ori, increase their theorists have tackled the subject. -

Sternentstehung

Sternentstehung - Star Formation Sommersemester 2009 Henrik Beuther 3.4 Today: Introduction & Overview 10.4 Karfreitag 17.4 Physical processes I 24.4 Physcial processes II 1.5 Tag der Arbeit 8.5 Collapse models I 15.5 Collapse models II 22.5 Observations of outflows and jets 29.5 No lecture 5.6 Jet theory (Christian Fendt) 12.6 Accretion disks 19.6 Protostellar evolution, stellar birthline, pre-main sequence evolution 26.6 High-mass star formation, clusters and the IMF 3.7 Extragalactic star formation (Eva Schinnerer) 10.7 Summary More Information and the current lecture files: http://www.mpia.de/homes/beuther/lecture_ss09.html [email protected] Topics today - The first core - The protostellar envelope structure - Protostellar evolution - Pre-main-sequence evolution Star Formation Paradigm The first core I - Contraction of core via ambipolar diffusion initially slow process. - When Σ/B reaches critical threshold, contraction speeds up, high density, core becomes opaque cooling less efficient T & P rise. - Interior still mainly molecular hydrogen important for final collapse The first core II - Temperature estimate based on viral theorem: 2T + 2U + W + M = 0 W = -2U (kinetic and magnetic energy approximated as 0) => -Gm2/R = -3mRT/µ => T = µGm/(3R R) -1 = 850K (m/0.05Msun) (R/5AU) --> significantly warmer than original core - With the addition of mass and further shrinking, it soon reaches 2000K, where collisional dissociation of H2 starts. --> Temperature increase less steep. - However, thermal energy per molecule at 2000K ~ 0.74eV compared to dissociation energy of H2 of ~ 4.48eV --> Even modest increase of dissociated H2 absorbs most of the gravitational energy from the collapse --> marginal increase in temperature and pressure - Region of atomic H spreads outward from center - Without significant T & P increase, the first core cannot keep equilibrium, hence the entire core becomes unstable, collapses and forms protostar. -

The Ages of Pre-Main-Sequence Stars

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 310, 360±376 (1999) The ages of pre-main-sequence stars Christopher A. Tout,1,2w Mario Livio2 and Ian A. Bonnell1 1Institute of Astronomy, The Observatories, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA 2Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA Accepted 1999 July 2. Received 1999 June 18; in original form 1998 November 19 ABSTRACT The position of pre-main-sequence or protostars in the Hertzsprung±Russell diagram is often used to determine their mass and age by comparison with pre-main-sequence evolution tracks. On the assumption that the stellar models are accurate, we demonstrate that, if the metallicity is known, the mass obtained is a good estimate. However, the age determination can be very misleading, because it is significantly (generally different by a factor of 2 to 5) dependent on the accretion rate and, for ages less than about 106 yr, the initial state of the star. We present a number of accreting protostellar tracks that can be used to determine age if the initial conditions can be determined and the underlying accretion rate has been constant in the past. Because of the balance established between the Kelvin±Helmholtz, contraction time-scale and the accretion time-scale, a pre-main-sequence star remembers its accretion history. Knowledge of the current accretion rate, together with an HR-diagram position, gives information about the rate of accretion in the past, but does not necessarily improve any age estimate. We do not claim that ages obtained by comparison with these particular accreting tracks are likely to be any more reliable than those from comparisons with non- accreting tracks.