Birkdale & Thorneside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Road Networked Artificial Islands and Finger Island Canal Estates on Australia’S Gold Coast

Absolute Waterfrontage: Road Networked Artificial Islands and Finger Island Canal Estates on Australia’s Gold Coast Philip Hayward Kagoshima University Research Center for the Pacific Islands, University of Technology Sydney, & Southern Cross University, Lismore [email protected] Christian Fleury University of Caen, Normandy [email protected] Abstract: The Gold Coast, an urban conurbation stretching along the Pacific seaboard and adjacent hinterland of south east Queensland, has developed rapidly since the 1950s. Much of its development has involved the modification of existing watercourses so as to produce stable areas of land suitable for medium and high density development. This article addresses one particular facet of this, the development of artificial islands and of estates of ‘finger islands’ (narrow, peninsular areas with direct waterfrontage) and the canalised waterways that facilitate them. The article commences with a discussion of the concepts behind such developments and the nomenclature that has accrued to them, highlighting the contradictions between branding of finger island estates and the actualities of their realisation. This discussion is supported by historical reference to earlier artificial island estates in Florida that provided a model for Australian developers. Case studies of three specific Gold Coast waterfront locations conclude the main body of the article, reflecting on factors related to the stability of their community environments. Keywords: Canal estates, finger islands, Florida, Gold Coast, island cities, shima, waterfront development © 2016 Philip Hayward & Christian Fleury Island Dynamics, Denmark - http://www.urbanislandstudies.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Hayward, P., & Fleury, C. -

CLEM7 - 2011 AUSTRALIAN CONSTRUCTION ACHIEVEMENT AWARD I Scope of Work

CLEM7 - 2011 AUSTRALIAN CONSTRUCTION ACHIEVEMENT AWARD i Scope of Work The Clem Jones Tunnel (CLEM7) is alternate route to the many roads that were Tunnel construction included: Brisbane’s first major road tunnel and the impassable or closed due to flooding. ■■ 41 evacuation cross passages between the longest and most technically advanced The Project was delivered by the Leighton two mainline tunnels every 120m; tunnel in Australia. The project has an overall Contractors and Baulderstone Bilfinger ■■ A long passage for evacuation from the length of 6.8km and links the Inner City Berger Joint Venture (LBBJV) under a lump Shafston Avenue ramps; Bypass (ICB) and Lutwyche Road in the sum design and construct (D&C) contract. A ■■ Five underground substations, each north of Brisbane to the Pacific Motorway ‘fast track’ design and construction approach consisting of four individual tunnels and Ipswich Road in the south, with an entry was adopted, which enabled LBBJV to excavated in the space between the two and exit ramp at Shafston Avenue. deliver the Project seven months ahead of mainline tunnels; The CLEM7 is the first critical component of schedule and on budget for their client ■■ A dedicated tunnel in each tube, beneath the Brisbane Lord Mayor’s TransApex vision RiverCity Motorway (RCM), who is in a the road surface for cabling; and to ease congestion and cater for the city’s Public-Private Partnership with Brisbane City future traffic needs. The tunnel, which has Council (Council). The Project cost $3 billion, ■■ A smoke duct in the ceiling of each tunnel, 2 the capacity to carry more than 100,000 which includes financing costs and the 9.2m in cross section, to extract smoke in vehicles a day, bypasses Brisbane’s CBD $2.1 billion of design and construction cost. -

South East Queensland Regional Plan RTI

l ] What happens next? --.- _.- __ _ _._-.- _ _ _ -._..-.-- _..__._.. __._-_.._ _.._._ _.- _ - _.._ _._ ] After the public display period Council will consider all commen1s before finalising the planning study for state Government consideration. The study will help the State Government decide ifand when -1 RTIthe investigation area will beRELEASE developed as a new urban community. .J J J @lUJ~ redlands... @lUJlR{ future -I RTI Document No. 461 I. Please quote: 2092 Monday, 27 April 2009 Mr Adam Souter Land Development Manager Edgarange Pty Ltd PO Box 181 Capalaba QLD 4157 Dear Mr Souter The Department of Infrastructure and Planning would like to thank you for your submission in response to the draft South East Queensland Regional Plan 2009-2031 (draft SEQ Regional Plan) released on the 7 December 2008. The Department of Infrastructure and Planning has registered your letter as a fonnal submission on the draft SEQ Regional Plan under the Integrated Planning Act 1997. It has been registered as submission number 2092. The issues raised in your submission will be evaluated and considered by the Department in the finalisation of the draft SEQ Regional Plan consultation report. The consultation report will summarise all issues raised during public consultation and will inform the review ofthe SEQ Regional Plan prior to its release in July 2009. If you wish to provide further information in support of your submission, please quote the above submission reference number. Thank you again for your interest in the draft SEQ Regional Plan. -

Triple AAA Housing Policy

Mornington Peninsula Shire Triple AAA Housing Policy Final Report June 2002 Gutteridge Haskins & Davey Pty Ltd GUTTERIDGE HASKINS & DAVEY PTY LTD ABN 39 008 488 373 380 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne Vic 3000 Australia Phone (03) 9278 2200 Fax (03) 9600 1300 REF NO: 31/010544/00 Gutteridge Haskins & Davey Pty Ltd Table of Contents Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................. 6 1 WHAT IS AAA HOUSING? .................................................................................. 10 1.1 STRATEGIC CONTEXT FOR THE STUDY ............................................................................ 10 1.2 STUDY PURPOSE .................................................................................................................. 11 1.3 DEFINING AAA HOUSING...................................................................................................... 11 1.4 STUDY METHODOLOGY ....................................................................................................... 12 2 THE HOUSING POLICY CONTEXT .................................................................... 13 2.1 NATIONAL AND STATE POLICY CONTEXT – PRIVATE HOUSING MARKET .................... 13 2.2 NATIONAL AND STATE POLICY CONTEXT – PUBLIC, SOCIAL & COMMUNITY HOUSING14 2.3 HOUSING PROGRAMS AND INITIATIVES............................................................................ 17 2.4 LOCAL HOUSING POLICY CONTEXT.................................................................................. -

SEPP Environment Explanation of Intended Effect

October 2017 SEPP (Environment) Explanation of Intended Effect Have your say 2 This Explanation of Intended Effect is available on the Department of Planning and Environment’s website: www.planning.nsw.gov.au/onexhibition You can make a submission online at the website or you can write to: Director, Planning Frameworks NSW Department of Planning and Environment GPO Box 39 Sydney NSW 2001 All submissions received will be made public in line with the Department of Planning and Environment’s objective to promote an open and transparent planning system. If you would like the Department of Planning and Environment to delete your personal information before publication, please make this clear in your submission. Before making a submission, please read our privacy statement at www.planning.nsw.gov.au/privacy October 2017 © Crown Copyright 2017 NSW Government Disclaimer While every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that this document is correct at the time of printing, the State of NSW, its agents and employees, disclaim any and all liability to any person in respect of anything or the consequences of anything done or omitted to be done in reliance or upon the whole or any part of this document. Copyright notice In keeping with the NSW Government’s commitment to encourage the availability of information, you are welcome to reproduce the material that appears in ‘SEPP (Environment) Explanation of Intended Effect’ for personal, in-house or non-commercial use without formal permission or charge. All other rights are reserved. If you wish to reproduce, alter, store or transmit material please contact the Department of Planning and Environment to request permission. -

Ordinary Council Meeting Held on 23

Port Macquarie−Hastings Council Settlement Shores Canal Estate Canal Maintenance Resident & Landowners Guidelines PORT MACQUARIE HASTINGS Prepared By: Technical Services and Natural Resources Sections APRIL 2006 Settlement Shores Canal Estate Canal Maintenance Contents Page No. 1. Introduction 3 2. Reference Documents 3 3. Responsibilities 3 4. Maintenance Works 4 5. Maintenance Works by Land Owners 5 6. Maintenance Works by Council 6 7. Design Details 6 9. Boating Facilities 7 10. Application and Fees 7 11. Funding 8 12. Monitoring 8 13. Contacts 9 APPENDIX A 10 APPENDIX B 12 APPENDIX C 18 APPENDIX D 20 Resident & Landowners Guidelines Page 2 Settlement Shores Canal Estate Canal Maintenance 1. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this document is to provide residents of the Settlement Shores Canal Estates with guidelines on undertaking certain works within the canals. The "canal" is generally described as the area between the revetment walls as shown in APPENDIX A. Works within the canals may involve any of the following:− • Maintenance dredging of canal beds • Rehabilitation of the beach zones • Repair of the revetment walls • Repair of boat ramps, jetties and mooring poles • Construction of boat ramps, jetties and mooring poles • Rehabilitation of rock protection • Repair of stormwater outlets This Guideline applies to all the canals except the new Broadwater & North/South Harbour canal development. 2. REFERENCE DOCUMENTS These guidelines form part of the following overall document set: − • Canal Maintenance Plan (CMP) 2004 • Canal Maintenance Plan − Review of Environmental Factors (REF) 2004 • Resident & Landowner Guidelines 2006 The CMP is a very detailed document which identifies, on an individual property basis, the condition of the existing canals, including the extent of sedimentation, condition of revetment walls, boat ramps, jetties and beach zones. -

INFORMATION MEMORANDUM 100 Dorsal Drive

INFORMATION MEMORANDUM 100 Dorsal Drive Information Memorandum Dated 26 March 2019 Holden Capital Partners ABN 696083461 AFSL 481944 www.holdencapitalpartners.com.au INFORMATION MEMORANDUM 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BORROWER AEC Projects Dorsal Drive Pty Ltd (ACN 617 398 839) (“The Borrower”). GUARANTORS Personal Guarantee for Debt, Interest and associated costs from Mr. Michael Choi. Corporate Guarantees from Micdor Consultants Pty Ltd (A.C.N 010838687) ATF Sheridan Investment Trust, and Pan Pacific (Australia) Pty Ltd A.C.N 056317278. LOCATION The project is located in the prestigious Aquatic Paradise canal estate at Birkdale. Birkdale is located 25km south-east of Brisbane's CBD. PROPERTY 100 Dorsal Drive, Birkdale Qld, 4159 further described as Lot 3 on Registered Plan No. 184228; Title Reference 16358097 and 232-234 Birkdale Road Birkdale, QLD, 4159 which are to be developed into 18 terrace homes. LOAN PURPOSE To complete construction of “100 Dorsal Drive”, comprising eighteen (18) terrace homes split between two-level, three-level and four-level terrace homes. LOAN TYPE Fully Committed progressively drawn 1st Mortgage Construction Facility. The facility will be drawn down on a progressive basis. Please refer to the ‘Debt Cashflow’ on page 13. LOAN TERM 11 months from the date of the First Advance. LOAN AMOUNT $6,800,000 exclusive of capitalised fees and interest. VALUATION A valuation report, dated 23 January 2019, addressed to Holden Capital Partners has confirmed the Market Value “As If Complete” for the Project at $17,807,888 inclusive of GST. KEY RATIOS Loan to Value Ratio (Excl GST) – equal or less than 47.1% including capitalised fees and interest. -

Costs and Coasts: an Empirical Assessment of Physical and Institutional Climate Adaptation Pathways Final Report

Costs and coasts: an empirical assessment of physical and institutional climate adaptation pathways Final Report Cameron Fletcher, Bruce Taylor, Alicia Rambaldi, Ben Harman, Sonja Heyenga, Renuka Ganegodage, Felix Lipkin and Ryan McAllister COSTS AND COASTS Costs and coasts: an empirical assessment of physical and institutional climate adaptation pathways CSIRO Climate Adaptation Flagship AUTHORS CS Fletcher (CSIRO), BM Taylor (CSIRO), AN Rambaldi (The University of Queensland), BP Harman (CSIRO), S Heyenga (CSIRO), KR Ganegodage (The University of Queensland), F Lipkin (CSIRO), RRJ McAllister (CSIRO) Published by the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility ISBN 978-1-925039-08-5 NCCARF Publication 37/13 © 2013 CSIRO This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright holders. Important disclaimer CSIRO advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore be made on that information without seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To the extent permitted by law, CSIRO (including its employees and consultants) excludes all liability to any person for any consequences, including but not limited to all losses, damages, costs, expenses and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained in it. Please cite this report as: CS Fletcher, BM Taylor, AN Rambaldi, BP Harman, S Heyenga, KR Ganegodage, F Lipkin, RRJ McAllister, 2013 Costs and coasts: an empirical assessment of physical and institutional climate adaptation pathways National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Gold Coast, pp. -

Connecting Brisbane © State of Queensland, June 2017

Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning Connecting Brisbane © State of Queensland, June 2017. Published by the Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning, 1 William Street, Brisbane Qld 4000, Australia. Licence: This work is licensed under the Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 Australia Licence. In essence, you are free to copy and distribute this material in any format, as long as you attribute the work to the State Of Queensland (Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning) and indicate if any changes have been made. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Attribution: The State of Queensland, Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of information. However, copyright protects this publication. The State of Queensland has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically but only if it is recognised as the owner of the copyright and this material remains unaltered. The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders of all cultural and linguistic backgrounds. If you have diffi culty understanding this publication and need a translator, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone the Queensland Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning on 13 QGOV (13 74 68). Disclaimer: While every care has been taken in preparing this publication, the State of Queensland accepts no responsibility for decisions or actions taken as a result of any data, information, statement or advice, expressed or implied, contained within. -

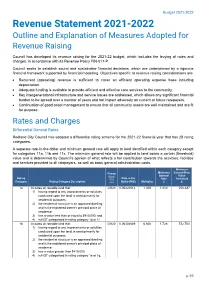

Revenue Statement 2021-2022 Outline and Explanation of Measures Adopted for Revenue Raising

Budget 2021-2022 Revenue Statement 2021-2022 Outline and Explanation of Measures Adopted for Revenue Raising Council has developed its revenue raising for the 2021-22 budget, which includes the levying of rates and charges, in accordance with its Revenue Policy FIN-017-P. Council seeks to establish sound and sustainable financial decisions, which are underpinned by a rigorous financial framework supported by financial modelling. Objectives specific to revenue raising considerations are: • Recurrent (operating) revenue is sufficient to cover an efficient operating expense base including depreciation. • Adequate funding is available to provide efficient and effective core services to the community. • Key intergenerational infrastructure and service issues are addressed, which allows any significant financial burden to be spread over a number of years and not impact adversely on current or future ratepayers. • Continuation of good asset management to ensure that all community assets are well maintained and are fit for purpose. Rates and Charges Differential General Rates Redland City Council has adopted a differential rating scheme for the 2021-22 financial year that has 28 rating categories. A separate rate‐in‐the‐dollar and minimum general rate will apply to land identified within each category except for categories 11a, 11b and 11c. The minimum general rate will be applied to land below a certain (threshold) value and is determined by Council’s opinion of what reflects a fair contribution towards the activities, facilities and services -

Artificial Tidal Lakes: Built for Humans, Home for Fish

Artificial tidal lakes: Built for humans, home for fish Author Waltham, Nathan J, Connolly, Rod M Published 2013 Journal Title Ecological Engineering DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.09.035 Copyright Statement © 2013 Elsevier Inc. This is the author-manuscript version of this paper. Reproduced in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/57047 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Cite As: NJ Waltham, RM Connolly (2013) Artificial tidal lakes: Built for humans, home for fish. Ecological Engineering 60:414-420 Artificial tidal lakes: built for humans, home for fish Nathan J. Waltham1,2*, Rod M. Connolly2 1Gold Coast City Council, PO Box 5042, Gold Coast Mail Centre, Queensland, 9729, Australia 2Australian Rivers Institute – Coasts and Estuaries, and School of Environment, Griffith University, Gold Coast campus, Queensland, 4222, Australia *Present Address. Australian Centre for Tropical Water and Aquatic Ecosystem Research (TropWATER), James Cook University, Queensland, 4811, Australia Tel.: +61 7 4781 4262; fax +61 7 4781 5589 e-mail address: [email protected] Abstract The construction of artificial, residential waterways to increase the opportunities for coastal properties with waterfrontage is a common and widespread practice. We describe the fish community from the world’s largest aggregation of artificial, estuarine lakes, the Burleigh Lake system that covers 280 ha on the Gold Coast in Queensland, Australia. Fish were collected from 30 sites in winter and spring of one year, and water salinity was measured 3-monthly for a 10 year period. -

Annual Report2008

ANNUAL REPORT2008 ABN 47 009 259 081 VICTORIA WESTERN AUSTRALIA MELBOURNE WANNEROO CONTENTS Carine GEELONG PORT PHILLIP BAY private esta t e PERTH Cedar Woods’ objective .................................................. 2 Harrisdale About Cedar Woods ....................................................... 3 Forrestdale 2008 highlights ............................................................... 4 Report to shareholders .................................................... 6 WELL LocaTED ROCKINGHAM Overview of projects ........................................................ 10 ProJECTS IN GrowTH Investor summary ............................................................ 16 CENTRES Corporate directory.......................................................... 18 MANDURAH 1 CEDAR WOODS PROPERTIES LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT2008 CEDAR WOOds’ OBJECTIVE Cedar Woods’ primarY OBJECTIVE IS TO CREATE VALUE FOR SHAREHOLDERS THROUGH GROWTH IN EARNINGS. IN MEETING OUR PRIMARY OBJECTIVE WE SEEK TO:- communicate the company’s progress to shareholders and the investment community; satisfy customers’ expectations through excellence in property development; align the interests of the company and its employees and provide employees with the opportunity for growth and development; have our citizenship recognised by the communities in which we operate and be recognised as environmentally responsible; and maintain the highest ethical standards. 2 ABOUT CEDAR WOODS ABOUT CEDAR WOODS Cedar Woods Properties Limited is an Australian property state awards, including