Intradermal Administration of Fractional Doses of Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine: a Dose-Sparing Option for Polio Immunization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incremental Costs of Introducing Jet Injection Technology for Delivery of Routine Childhood Vaccinations: Comparative Analysis from Brazil, India, and South Africa

Vaccine 29 (2011) 969–975 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Vaccine journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vaccine Incremental costs of introducing jet injection technology for delivery of routine childhood vaccinations: Comparative analysis from Brazil, India, and South Africa Ulla K. Griffiths a,∗, Andreia C. Santos a, Neeti Nundy b, Erica Jacoby b, Dipika Matthias b a London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Tavistock Place, London WC1H 9SH, UK b PATH, 2201 Westlake Avenue, Suite 200, Seattle, WA 98121, USA article info abstract Article history: Background: Disposable-syringe jet injectors (DSJIs) have the potential to deliver vaccines safely and Received 14 May 2010 affordably to millions of children around the world. We estimated the incremental costs of transitioning Received in revised form 9 November 2010 from needles and syringes to delivering childhood vaccines with DSJIs in Brazil, India, and South Africa. Accepted 15 November 2010 Methods: Two scenarios were assessed: (1) DSJI delivery of all vaccines at current dose and depth; (2) a Available online 27 November 2010 change to intradermal (ID) delivery with DSJIs for hepatitis B and yellow fever vaccines, while the other vaccines are delivered by DSJIs at current dose and depth. The main advantage of ID delivery is that only Keywords: a small fraction of the standard dose may be needed to obtain an immune response similar to that of Vaccine Jet injector subcutaneous or intramuscular injection. Cost categories included were vaccines, injection equipment, Costs waste management, and vaccine transport. Some delivery cost items, such as training and personnel Brazil were excluded as were treatment cost savings caused by a reduction in diseases transmitted due to India unsafe injections. -

For Nexplanon® Insertion and Removal G

Wilson et al. Contraception and Reproductive Medicine (2020) 5:1 Contraception and https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-020-00104-x Reproductive Medicine RESEARCH Open Access Comparison of traditional anesthesia method and jet injector anesthesia method (MadaJet XL®) for Nexplanon® insertion and removal G. Anthony Wilson* , Julie W. Jeter, William S. Dabbs, Amy Barger Stevens, Robert E. Heidel and Shaunta’ M. Chamberlin Abstract Background: This study compared a needle-free anesthesia method with traditional local anesthesia for insertion and removal of Nexplanon® long-acting removable contraceptive device. In our clinic, patients often avoid this highly effective form of contraception due to fear of needles. We sought to determine if patients perceived a difference in pain with the injection, anxiety level or pain with the procedure when local anesthesia was given with a needle v/s a needle-free jet injector device. Methods: Patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups: jet injector or needle lidocaine delivery. Outcomes were ease of use, patient anxiety level, painfulness, and efficacy of anesthesia method. Results: Patient pain perception with administration of jet injector lidocaine was statistically lower than traditional needle with no difference in anxiety or ease of use, or efficacy of the anesthesia. Conclusion: The jet injector device is a reasonable alternative to needle injection delivery of anesthesia prior to insertion/removal of Nexplanon® device. Further studies may determine whether this needle-free alternative for administration of local anesthetic would result in more women choosing Nexplanon® as a contraceptive method. Keywords: Local anesthetic, Nexplanon®, Patient anxiety Background injection of lidocaine differed between the methods of As with many procedures [1, 2], patients often cite a fear delivery, and whether the presence or absence of needles of needles as a major reason to decline Nexplanon® in the anesthesia method affected patient anxiety level. -

Technical Considerations for Pen, Jet, and Related Injectors Intended for Use with Drugs and Biological Products

Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff: Technical Considerations for Pen, Jet, and Related Injectors Intended for Use with Drugs and Biological Products Additional copies are available from: Office of Combination Products Office of Special Medical Programs Office of the Commissioner Food and Drug Administration 10903 New Hampshire Avenue, WO-32 Hub 5129 Silver Spring, MD 20993 (Tel) 301-796-8930 (Fax) 301-796-8619 http://www.fda.gov/CombinationProducts/default.htm This document finalizes the draft guidance issued in April 2009. For questions regarding this document, contact the Office of Combination Products at [email protected] or Patricia Y. Love, MD at 301-796-8933 or [email protected] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Center for Drug Evaluation Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, and Office of Combination Products in the Office of the Commissioner June 2013 Contains Nonbinding Recommendations Table of Contents INTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................................3 BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................................4 SECTION I: SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS.............................5 A. INJECTOR DESCRIPTION .............................................................................................5 B. DESIGN FEATURES.........................................................................................................9 -

Growth Hormone Treatment Without a Needle Using the Preci-Jet 50

Archives of Disease in Childhood 1997;76:65–67 65 Growth hormone treatment without a needle Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.76.1.65 on 1 January 1997. Downloaded from using the Preci-Jet 50 transjector P Bareille, M MacSwiney, A Albanese, C De Vile, R Stanhope Abstract Patients and methods A new delivery system (Preci-Jet 50) Twenty eight patients (11 girls, 17 boys) were which administers growth hormone randomly selected from the endocrine clinic at through the skin using high pressure and Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children. without a needle was evaluated. This All patients were receiving growth hormone device was inconvenient and painful com- treatment, 19 through an autoinjector and nine pared with a pen injection system. The with needles and syringes. None was using a conclusion is that the Preci-Jet is not the pen injector system at that time but nine had used one previously. The exclusion criteria panacea for solving the problem of com- were bleeding disorders and diseases of colla- pliance with subcutaneous growth hor- gen synthesis. Mean age was 10.1 (range mone injections. 5.7–16.7) years. The growth hormone dose ( 1997;76:65–67) Arch Dis Child range was from 15 to 30 IU/m2 body surface area/week. The subjects were randomly subdi- Keywords: growth hormone treatment; transcutaneous high pressure administration (jet); needle phobia. vided into two groups, A and B. Sex distribu- tion was similar in both groups but mean age diVered, with values of 8.7 and 11.2 years in groups A and B respectively. -

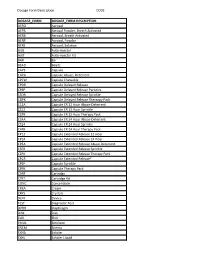

Dosage Form Description CODE

Dosage Form Description CODE DOSAGE_FORM DOSAGE_FORM DESCRIPTION AERO Aerosol AEPB Aerosol Powder, Breath Activated AERB Aerosol, Breath Activated AERP Aerosol, Powder AERS Aerosol, Solution AUIJ Auto-injector AJKT Auto-injector Kit BAR Bar BEAD Beads CAPS Capsule CAPA Capsule Abuse- Deterrent CPCW Capsule Chewable CPDR Capsule Delayed Release CPEP Capsule Delayed Release Particles CSDR Capsule Delayed Release Sprinkle CDPK Capsule Delayed Release Thereapy Pack C12A Capsule ER 12 Hour Abuse-Deterrent CS12 Capsule ER 12 Hour Sprinkle C2PK Capsule ER 12 Hour Therapy Pack C24A Capsule ER 24 Hour Abuse-Deterrent CS24 Capsule ER 24 Hour Sprinkle C4PK Capsule ER 24 Hour Therapy Pack CP12 Capsule Extended Release 12 Hour CP24 Capsule Extended Release 24 Hour CPEA Capsule Extended Release Abuse-Deterrent CSER Capsule Extended Release Sprinkle CEPK Capsule Extended Release Therapy Pack CPCR Capsule Extended Release* CPSP Capsule Sprinkle CPPK Capsule Therapy Pack CART Cartridge CTKT Cartridge Kit CONC Concentrate CREA Cream CRYS Crystals DEVI Device TEST Diagnostic Test DPRH Diaphragm DISK Disk ELIX Elixir EMUL Emulsion ENEM Enema EXHA Exhaler EXHL Exhaler Liquid Dosage Form Description CODE DOSAGE_FORM DOSAGE_FORM DESCRIPTION EXHP Exhaler Powder EXHS Exhaler Solution EXHU Exhaler Suspension FILM Film FLAK Flakes EXTR Fluid Extract FOAM Foam GAS Gas GEL Gel SOLG Gel Forming Solution GRAN Granules GREF Granules Effervescent GUM Gum IMPL Implant INHA Inhaler INJ Injectable INST Insert IUD Intrauterine Device JTAJ Jet-injector (Needleless) JTKT Jet-injector -

Cold and Flu Season

The DrugSmith is The Monthly Newsletter of The Smith Drug Company A Division of J M Smith Corporation Spartanburg, SC • Paragould, AR • Valdosta, GA Cold and Flu Season National Flu Vaccination Week World AIDS Month Introducing: Inject-Safe™ Barrier Bandage The first and only bandage designed specifically for injections. • Improved Safety Relieving Symptoms of the Common Cold 4 • Lower Cost National Influenza Vaccination Week 2016 6 • More Convenient • Less Pain What's New With The Flu? 7 Why Get A Flu Shot? 9 HealthWise Connect: Coming Soon! 11 World AIDS Day 12 Colon Rectal Cancer: Basic Facts 16 Healthwise™ Clinical Solutions Healthwise™ Circular Program DollarWise™ Program Good Sense® Controlled Label Program Greeting Cards Program Continuing Education Gift and Trade Show ™ Benefits of the Inject-Safe™ Barrier Bandage Rx QuickShip Third Party Station Inject-Safe™ Barrier Bandages self-seal to help contain Pharmacy First bleeding following an injection. DrugSmith™ Monthly Newsletter Consistent with “Universal Precautions” established by Smith Weekly e-Blast OSHA. Diabeticare Program Hamacher Retail Zone Pricing Protects the healthcare provider from coming into contact with potential blood borne pathogens. Home Health Care Catalog HealthWise Signage Program Allows healthcare provider to use both hands to dispose of Smith Gift Box Gift Category the needle. Vials and Vitamin Program Meets OSHA Blood borne Pathogen Standard's definition Direct Mail Advertising of "Engineering Control," for use to reduce employee Well Staffed Customer Service -

Maxillo, Pain EYE & ENT DNB Q & A

Dr. Azam’s Notes in Anesthesiology Postgraduates appearing 3rd Edition for MD, DNB & DA Exams Maxfax, Pain, Eye, ENT & Orthopedic Edited by: Dr. Azam Consultant Anesthesiologist & Critical Care Specialist www.drazam.com 2 Dr Azam’s Notes in Anesthesiology 2013 Dedication To Mohammed Shafiulla, my father, my oxygen, companion, and best friend; for being my major pillar of support and making this vision a reality. Thank you for your continual sacrifices with boundless love and limitless gratitude, for the sake of your children. I owe you a debt I can never repay. I also would like to thank my mom (Naaz Shafi), my wife (Roohi Azam), my two lovely kids (Falaq Zohaa & Mohammed Izaan), for their support, ideas, patience, and encouragement during the many hours of writing this book. Finally, I would like to thank my teachers (Dr.Manjunath Jajoor & team) & Dr T. A. Patil . The dream begins with a teacher who believes in you, who tugs and pushes and leads you to the next plateau, sometimes poking you with a sharp stick called "truth." 3 Dr Azam’s Notes in Anesthesiology 2013 Dr Azam’s Notes in Anesthesiology 2013 A NOTE TO THE READER Anesthesiology is an ever-changing field. Standard safety precautions must be followed, but as new research and clinical experience broaden our knowledge, changes in treatment and drug therapy may become necessary or appropriate. Readers are advised to check the most current product information provided by the manufacturer of each drug to be administered to verify the recommended dose, the method and duration of administration, and contraindications. -

• the PDL Is a List of Over 100 Therapeutic Classes Reviewed by the Pharmaceutical & Therapeutics (P&T) Committee

Louisiana Medicaid Preferred Drug List (PDL)/Non-Preferred Drug List (NPDL) http://ldh.la.gov/assets/HealthyLa/Pharmacy/PDL.pdf • The PDL is a list of over 100 therapeutic classes reviewed by the Pharmaceutical & Therapeutics (P&T) committee. In addition, there are medications and/or classes of medications that are not reviewed by the committee. Unless there is a clinical pre-authorization requirement for the entire class (as noted on the last page of the PDL) these medications will continue to be covered without prior authorization. Examples: spironolactone, hydrochlorothiazide, amoxicillin suspension • There is a mandatory generic substitution unless the brand is preferred and the generic is non-preferred. When the brand is preferred and the generic is non-preferred, no special notations are required by the prescriber and the pharmacist enters “9” in the DAW field 408-D8. • When the brand is non-preferred and the prescriber has determined it to be medically necessary, “Brand medically necessary” or “Brand necessary” must be written on the prescription in the prescriber’s handwriting or via an electronic prescription and the pharmacist enters “1” in the DAW field 408-D8. For more information, please refer to the following policy: https://www.lamedicaid.com/provweb1/Providermanuals/manuals/PHARMACY/PHARMACY.pdf • To locate any medication on this list, you may use the keyboard shortcut CTRL + F to search. • New medications that enter the marketplace in classes reviewed by P&T committee will be considered non-preferred requiring prior authorization until the next P&T committee meeting. Please refer to the following criteria: New Drugs Introduced into the Market / Non-Preferred • The PDL is arranged by therapeutic class with an item number and may contain a subset of medications under each therapeutic class. -

Adverse Events: the Role of Formulations and Delivery Systems

12 Adverse events: the role of formulations and delivery systems 12.1 Introduction 482 12.11 Reactions to impurities 494 12.2 Excipient effects 483 12.12 Crystallisation 503 12.3 E-numbers 485 12.13 Abnormal bioavailability and adverse events 504 12.4 Cross-reactivity of drugs 487 12.14 Photochemical reactions and 12.5 Non-ionic surfactants 487 photoinduced reactions 506 12.6 Polyoxyethylene glycols 488 12.15 Conclusions 509 12.7 Adjuvants as therapeutic substances 488 References 510 12.8 Active excipients in multiple therapies 490 Further reading 511 12.9 Influence of dosage form type 491 12.10 Tear films and eye drops 492 The main purpose of formulations is to deliver active substances in accurate doses in medicines that are stable and of a high and consistent quality. Drugs are often the smallest proportion of a medicine, and the variety of other ingredients within most dose forms is large. Some of these excipients serve more than one purpose and some have some biological activity. The reason we discuss in this textbook adverse events which may follow from administration of medicines is that some of the problems that arise are the result of excipients interacting physically or chemically with drugs or with themselves, or creating instability or, in some instances, having biological activity of their own. That activity may not be a direct pharmacological or toxicological action, though some agents, such as some non-ionic surfactants, may cause anaphylactic responses or affect drug absorption rates and extent by solubilisation effects or by acting on P-glycoprotein receptors, thus influencing bioavailability. -

Characterization of Jets for Impulsively-Started Needle-Free Jet Injectors: Influence of fluid Properties T

Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 53 (2019) 101167 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jddst Characterization of jets for impulsively-started needle-free jet injectors: Influence of fluid properties T Pankaj Rohillaa, Yatish S. Ranea, Idera Lawala, Andrew Le Blanca, Justin Davisa, James B. Thomasa, Cormak Weeksa, Whitney Tranb, Paul Fisherc, Kate E. Broderickc, Jonathan A. Simmonsa,d, Jeremy O. Marstona,* a Department of Chemical Engineering, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, 79409, USA b Department of Mathematics & Statistics, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, 79409, USA c Inovio Pharmaceuticals, 10480 Wateridge Circle, San Diego, CA, 92121, USA d Department of Mechanical Engineering, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, 79409, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: An experimental study was performed to assess the hydrodynamics of liquid jets used for needle-free injection, Needle-free injection where the typical orifice diameter is ~155 μm and velocity is in range of ~ 60–140 m/s. The jet is impulsively Liquid jet started by a spring-piston that forces a plunger through a cartridge filled with the liquid. Liquid exiting the Impact force orifice then forms a jet. However, despite a fixed spring force, the jet speed can vary significantly depending on Rheology the fluid physical properties - in particular - the effective viscosity. Since in practice a wide range of fluids may be used for injection, we seek herein to study the jet formation and speed for a broad range of fluids, char- acterized by viscosity or rheological profile. In addition, we also characterize the jet performance with a peak impact force, measured by a dynamic load cell, and ex-vivo injection experiments on porcine tissue. -

A COVID-19 Vaccine May Come Without a Needle

A COVID-19 vaccine may come without a needle, the latest vaccine to protect without jabbing 1 October 2020, by Vasso Apostolopoulos, Maja Husaric, Maximilian De Courten middle of the 20th century, and were used to deliver vaccines against typhus, polio and smallpox. A hepatitis B outbreak linked to their use meant they were discontinued in the 1980s. However, research picked up again in the 1990s. Variations included a spring-loaded jet injector (a spring is released to deliver the drug), a battery-powered jet injector, and a gas-powered jet injector. Jet injection has also been used in dental care to deliver local anesthetic. Beyond jet injection, oral vaccines including rotavirus, cholera, polio and typhoid have been Oral vaccines have been around for many years. Credit: around for several decades, and are still used Shutterstock today in various parts of the world. They can come as a liquid or tablet. More recently, researchers and biotechnology Vaccines are traditionally administered with a companies have developed vaccines you inhale, needle, but this isn't the only way. For example, such as nasal sprays, as well as skin patches. certain vaccines can be delivered orally, as a drop These are mostly still in clinical testing. on the tongue, or via a jet-like device. DNA-based vaccines and the gene gun Vaccines that appear particularly suitable to needle -free technology are DNA-based ones, including a DNA vaccines were a chance discovery as a result COVID-19 vaccine being developed in Australia. of early gene therapy experiments in the 1990s, where injecting DNA into the muscle unexpectedly Needle-free vaccines are attractive as they cause generated an immune response. -

372 Part 872—Dental Devices

§ 870.5925 21 CFR Ch. I (4–1–16 Edition) (iii) Testing to demonstrate compat- 872.1840 Dental x-ray position indicating de- ibility with the indicated external con- vice. troller. 872.1850 Lead-lined position indicator. 872.1870 Sulfide detection device. (iv) Shelf life testing. 872.1905 Dental x-ray film holder. (3) Animal testing must demonstrate 872.2050 Dental sonography device. that the device does not cause esopha- 872.2060 Jaw tracking device. geal injury and that body temperature remains within appropriate boundaries Subpart C [Reserved] under anticipated conditions of use. (4) Labeling must include the fol- Subpart D—Prosthetic Devices lowing: 872.3060 Noble metal alloy. (i) Detailed insertion instructions. 872.3070 Dental amalgam, mercury, and (ii) Warning against attaching the amalgam alloy. device to unintended connections, such 872.3080 Mercury and alloy dispenser. as external controllers for which the 872.3100 Dental amalgamator. device is not indicated, or pressurized 872.3110 Dental amalgam capsule. 872.3130 Preformed anchor. air outlets instead of vacuum outlets 872.3140 Resin applicator. for those devices, including gastric suc- 872.3150 Articulator. tion. 872.3165 Precision attachment. (iii) The operating parameters, name, 872.3200 Resin tooth bonding agent. and model number of the indicated ex- 872.3220 Facebow. ternal controller. 872.3240 Dental bur. (iv) The intended duration of use. 872.3250 Calcium hydroxide cavity liner. 872.3260 Cavity varnish. [80 FR 49896, Aug. 18, 2015] 872.3275 Dental cement. 872.3285 Preformed clasp. § 870.5925 Automatic rotating tour- 872.3300 Hydrophilic resin coating for den- niquet. tures. 872.3310 Coating material for resin fillings.