British Television by Keith G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representations of British Probation

British Journal of Community Justice ©2012 Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield ISSN 1475-0279 Vol. 10(2): 5-23 REPRESENTATIONS OF BRITISH PROBATION OFFICERS IN FILM, TELEVISION DRAMA AND NOVELS 1948-2012 Mike Nellis, Emeritus Professor of Criminal and Community Justice, School of Law, University of Strathclyde Abstract This paper offers an overview of representations of the British probation service in three fictional media over a sixty year period, up to the present time. While there were never as many, and they were never as renowned as representations of police, lawyers and doctors, there are arguably more than has generally been realised. Broadly speaking - although there have always been individual exceptions to general trends - there has been a shift from supportive and optimistic representations to cynical and disillusioned ones, in which the viability of showing care and compassion to offenders is questioned or mocked. This mirrors wider political attempts to change the traditionally welfare-oriented culture of the service to something more punitive. The somewhat random and intermittent production of probation novels, films and television series over the period in questions has had no discernible cumulative impact on public understanding of probation, and it is suggested that the relative absence of iconic media portrayals of its officers, comparable to those achieved in police, legal and medical fiction, has made it more difficult to sustain credible debates about rehabilitation in popular culture. Introduction One of the problems the Probation Service has is that it is not very photogenic. We live with an image driven media and society and unfortunately probation doesn’t present itself well, certainly on television. -

On the Purple Circuit with Bill Kaiser Volume 8, Number 1 the MANBITES DOG THEATER ISSUE

On The Purple Circuit With Bill Kaiser Volume 8, Number 1 THE MANBITES DOG THEATER ISSUE The 9th Annual AIDS Theater Festival will be held during the 11th WELCOME TO ON THE PURPLE CIRCUIT! National HIV/AIDS Update Conference in San Francisco Mar 23- 26,1999.In addition the 6th Latino/a AIDS Theater Festival will take Welcome to the first issue of our 8th year of On The Purple Circuit. It place at the same time. Congratulations to the participants and to has been my honor and pleasure to report on the phenomenon of the man that has made it all happen, AD Hank Tavera! For info on Gay, Lesbian, Queer, Bi and Trans theatre, and performance to you events call 415-554-8436 or fax 415-554-8444. from across the US and around the world. It seems strange to me that while so many pundits and Gay playwrights who have made it in I am very concerned about the Bruce Mirkin case that many of you the mainstream say there is no such thing or that it is past (or is it may have read about in The Village Voice or elsewhere. Bruce is a post) that more is happening than ever before! San Francisco journalist who has worked on issues of importance to our community for a long time including that of Gay youth. He I am dedicating this issue to Manbites Dog Theater in Durham, North communicated online with a supposedly Gay teenager and set up a Carolina. I am so proud of these folks in Jesse Helms backyard who meeting to investigate the story when he stumbled into a produce great works of art and succeed at it! They have just opened Sacramento police sting operation. -

ANDERSEN PRESS AUTUMN 2019 PICTURE BOOKS PICTURE BOOKS Sally Nicholls Bethan Woollvin Alex G

ANDERSEN PRESS AUTUMN 2019 PICTURE BOOKS PICTURE BOOKS Sally Nicholls Bethan Woollvin Alex G. Griffiths THE BUTTON BOOK THE BUG Here’s a button. I wonder COLLECTOR what happens when you After George visits the press it? Museum of Wildlife with Grandad, all he can think From a singing button to a about is bugs! The very next tickle button, from a rude sound day he goes out hunting, but button to a mysterious white he soon finds there are no button, there’s only one way more insects left in the to find out what they do . garden, and the ones he has Come along on a magical captured in jars don’t look journey, powered only by very happy… George is imagination and play, from about to learn exactly why award-winning Sally Nicholls bugs are so important. and Bethan Woollvin. OCT 2019 9781783447749 32pp HB 2+ EBook available 250 x 250mm £12.99 JUL 2019 9781783447688 32pp HB 3+ SALLY NICHOLLS is known for her bestselling novels for children and teenagers. Her first EBook available 280 x 240mm £12.99 novel won the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize and more recently she has been shortlisted for the National Book Award, the YA Book Prize and the Carnegie Medal for Things a Bright Girl Can Do. The Button Book is her first picture book, inspired by her own children’s reading habits. Twitter: @Sally_Nicholls BETHAN WOOLLVIN is the author and illustrator of Macmillan Prize winning Little Red, which was chosen as one of The New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Books 2016. -

Dear Secretary Salazar: I Strongly

Dear Secretary Salazar: I strongly oppose the Bush administration's illegal and illogical regulations under Section 4(d) and Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, which reduce protections to polar bears and create an exemption for greenhouse gas emissions. I request that you revoke these regulations immediately, within the 60-day window provided by Congress for their removal. The Endangered Species Act has a proven track record of success at reducing all threats to species, and it makes absolutely no sense, scientifically or legally, to exempt greenhouse gas emissions -- the number-one threat to the polar bear -- from this successful system. I urge you to take this critically important step in restoring scientific integrity at the Department of Interior by rescinding both of Bush's illegal regulations reducing protections to polar bears. Sarah Bergman, Tucson, AZ James Shannon, Fairfield Bay, AR Keri Dixon, Tucson, AZ Ben Blanding, Lynnwood, WA Bill Haskins, Sacramento, CA Sher Surratt, Middleburg Hts, OH Kassie Siegel, Joshua Tree, CA Sigrid Schraube, Schoeneck Susan Arnot, San Francisco, CA Stephanie Mitchell, Los Angeles, CA Sarah Taylor, NY, NY Simona Bixler, Apo Ae, AE Stephan Flint, Moscow, ID Steve Fardys, Los Angeles, CA Shelbi Kepler, Temecula, CA Kim Crawford, NJ Mary Trujillo, Alhambra, CA Diane Jarosy, Letchworth Garden City,Herts Shari Carpenter, Fallbrook, CA Sheila Kilpatrick, Virginia Beach, VA Kierã¡N Suckling, Tucson, AZ Steve Atkins, Bath Sharon Fleisher, Huntington Station, NY Hans Morgenstern, Miami, FL Shawn Alma, -

Queer Alchemy: Fabulousness in Gay Male Literature and Film

QUEER ALCHEMY QUEER ALCHEMY: FABULOUSNESS IN GAY MALE LITERATURE AND FILM By ANDREW JOHN BUZNY, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Andrew John Buzny, August 2010 MASTER OF ARTS (2010) McMaster University' (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Queer Alchemy: Fabulousness in Gay Male Literature and Film AUTHOR: Andrew John Buzny, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Lorraine York NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 124pp. 11 ABSTRACT This thesis prioritizes the role of the Fabulous, an underdeveloped critical concept, in the construction of gay male literature and film. Building on Heather Love's observation that queer communities possess a seemingly magical ability to transform shame into pride - queer alchemy - I argue that gay males have created a genre of fiction that draws on this alchemical power through their uses of the Fabulous: fabulous realism. To highlight the multifarious nature of the Fabulous, I examine Thomas Gustafson's film Were the World Mine, Tomson Highway's novel Kiss ofthe Fur Queen, and Quentin Crisp's memoir The Naked Civil Servant. 111 ACKNO~EDGEMENTS This thesis would not have reached completion without the continuing aid and encouragement of a number of fabulous people. I am extremely thankful to have been blessed with such a rigorous, encouraging, compassionate supervisor, Dr. Lorraine York, who despite my constant erratic behaviour, and disloyalty to my original proposal has remained a strong supporter of this project: THANK YOU! I would also like to thank my first reader, Dr. Sarah Brophy for providing me with multiple opportunities to grow in~ellectually throughout the past year, and during my entire tenure at McMaster University. -

'Drowning in Here in His Bloody Sea' : Exploring TV Cop Drama's

'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Cummins, ID and King, M http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2015.1112387 Title 'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Authors Cummins, ID and King, M Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/38760/ Published Date 2015 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Introduction The Criminal Justice System is a part of society that is both familiar and hidden. It is familiar in that a large part of daily news and television drama is devoted to it (Carrabine, 2008; Jewkes, 2011). It is hidden in the sense that the majority of the population have little, if any, direct contact with the Criminal Justice System, meaning that the media may be a major force in shaping their views on crime and policing (Carrabine, 2008). As Reiner (2000) notes, the debate about the relationship between the media, policing, and crime has been a key feature of wider societal concerns about crime since the establishment of the modern police force. -

(Pdf) Download

St. David’s Welsh Society of the Suncoast MARCH 2016 welshsocietyofthesuncoast.org EVERYONE INVITED CROESO St. David’s Day Banquet Regular meetings of the St. David’s Welsh Soci- March 6 ety of the Suncoast are held at noon on the third Kally K s Restaurant Tuesday of the month. From October to April at the Lake Seminole Presbyterian Church, 8600 113th Street N, Seminole Florida (right on the corner). RESERVATION TIME A potluck luncheon and program entertain all FOR BANQUET persons with an interest in celebrating Welsh heritage. We have great fun so bring a friend to This year we are trying a new location for our socialize. (They do not even have to be Welsh St. David’s Day Banquet. We will gather at the to be welcome. same time (4:00 social hour) at a new but fa- miliar location—Kally Ks Restaurant on Main Street in Dunedin. It has been the site of many successful summer luncheons. Donna Anderson, who has enchanted us be- fore with her lovely voice, will entertain us after dinner. She always brings a selection of Welsh Please note that the only meeting in March will be songs and modern popular tunes. the banquet on March 6. If you have not yet made Our reservation form is at the end of this news- your reservations, please do so now. We look for- letter along with your dinner choices. Again ward to seeing everyone together. The next regular this year there are children’s selections for the meeting will be April 19. young ones. -

ABC KIDS/COMEDY Program Guide: Week 23 Index 1 | Page

ABC KIDS/COMEDY Program Guide: Week 23 Index 1 | P a g e ABC KIDS/COMEDY Program Guide: Week 23 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 31 May 2020 ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Monday, 1 June 2020 ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Tuesday, 2 June 2020 .......................................................................................................................................... 15 Wednesday, 3 June 2020 .................................................................................................................................... 21 Thursday, 4 June 2020 ........................................................................................................................................ 27 Friday, 5 June 2020 ............................................................................................................................................. 33 Saturday, 6 June 2020 ......................................................................................................................................... 39 2 | P a g e ABC KIDS/COMEDY Program Guide: Week 23 Sunday 31 May 2020 Program Guide Sunday, 31 May 2020 5:00am The Hive (Repeat,G) 5:10am Pocoyo -

Birmingham Cover Online.Qxp Birmingham Cover 29/04/2016 09:26 Page 1

Birmingham Cover Online.qxp_Birmingham Cover 29/04/2016 09:26 Page 1 Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands Birmingham ’ Whatwww.whatsonlive.co.uk sISSUE On 365 MAY 2016 EDDIE IZZARD IN THE MIDLANDS inside: Yourthe 16-pagelist week by week listings guide Julian Clary Celebrating 30 years of Mincing! The Overtones (FP- June 16).qxp_Layout 1 09/05/2016 14:55 Page 1 Contents May Birmingham.qxp_Layout 1 20/04/2016 16:17 Page 1 May 2016 Contents Political Mother - Hofesh Shechter’s acclaimed work at The Rep. Feature page 20 Laura Mvula Katherine Ryan King Lear the list performs The Dreaming Room Canadian funny lady at the Don Warrington takes the lead Your 16-page on home turf Town Hall in The Bard’s searing tragedy week-by-week listings guide page 15 page 28 page 31 page 51 inside: 4. First Word 11. Food 14. Music 28. Comedy 31. Theatre 38. Film 42. Visual Arts 45. Events @whatsonbrum fb.com/whatsonbirmingham Birmingham What’s On Magazine Birmingham What’s On Magazine Editorial Director: Davina Evans [email protected] 01743 281708 ’ Sales & Marketing: Lei Woodhouse [email protected] 01743 281703 Chris Horton [email protected] 01743 281704 Whats On Matt Rothwell [email protected] 01743 281719 MAGAZINE GROUP Editorial: Lauren Foster [email protected] 01743 281707 Sue Jones [email protected] 01743 281705 Brian O’Faolain [email protected] 01743 281701 Ryan Humphreys [email protected] 01743 281722 Abi Whitehouse [email protected] 01743 281716 Adrian Parker [email protected] 01743 281714 Contributors: Graham Bostock, James Cameron-Wilson, Heather Kincaid, Adam Jaremko, Kathryn Ewing, David Vincent Publisher and CEO: Martin Monahan Accounts Administrator: Julia Perry [email protected] 01743 281717 This publication is printed on paper from a sustainable source and is produced without the use of elemental chlorine. -

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

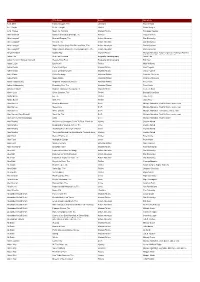

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. -

Queer Icon Penny Arcade NYC USA

Queer icON Penny ARCADE NYC USA WE PAY TRIBUTE TO THE LEGENDARY WISDOM AND LIGHTNING WIT OF THE SElf-PROCLAIMED ‘OLD QUEEn’ oF THE UNDERGROUND Words BEN WALTERS | Photographs DAVID EdwARDS | Art Direction MARTIN PERRY Styling DAVID HAWKINS & POP KAMPOL | Hair CHRISTIAN LANDON | Make-up JOEY CHOY USING M.A.C IT’S A HOT JULY AFTERNOON IN 2009 AND I’M IN PENNy ARCADE’S FOURTH-FLOOR APARTMENT ON THE LOWER EASt SIde of MANHATTan. The pink and blue walls are covered in portraits, from Raeburn’s ‘Skating Minister’ to Martin Luther King to a STOP sign over which Penny’s own image is painted (good luck stopping this one). A framed heart sits over the fridge, Day of the Dead skulls spill along a sideboard. Arcade sits at a wrought-iron table, before her a pile of fabric, a bowl of fruit, two laptops, a red purse, and a pack of American Spirits. She wears a striped top, cargo pants, and scuffed pink Crocs, hair pulled back from her face, no make-up. ‘I had asked if I could audition to play myself,’ she says, ‘And the word came back that only a movie star or a television star could play Penny Arcade!’ She’s talking about the television film, An Englishman in New York, the follow-up to The Naked Civil Servant, in which John Hurt reprises his role as Quentin Crisp. Arcade, a regular collaborator and close friend of Crisp’s throughout his last decade, is played by Cynthia Nixon, star of Sex PENNY ARCADE and the City – one of the shows Arcade has blamed for the suburbanisation of her beloved New York City. -

Helen Smith Full Thesis

A Study of Working-Class Men Who Desired Other Men in the North of England, c.1895 - 1957 Helen Smith Department of History A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2012 Abstract This thesis is the first detailed academic study of non-metropolitan men who desired other men in England during the period 1895-1957. It places issues of class, masculinity and regionality alongside sexuality in seeking to understand how men experienced their emotional and sexual relationships with each other. It argues that fluid notions of sexuality were rooted in deeply embedded notions of class and region. The thesis examines the six decades from 1895 to 1957 in an attempt to explore patterns of change over a broad period and uses a wide variety of sources such as legal records, newspapers, letters, social surveys and oral histories to achieve this. Amongst northern working men, ‘normality’ and ‘good character’ were not necessarily disrupted by same sex desire. As long as a man was a good, reliable worker, many other potential transgressions could be forgiven or overlooked. This type of tolerance of (or ambivalence to) same sex desire was shaken by affluence and the increased visibility of men with a clear sexuality from the 1950s and into the era of decriminalisation. The thesis analyses patterns of work, sex, friendship and sociability throughout the period to understand how these traditions of tolerance and ambivalence were formed and why they eventually came to an end. Although the impact of affluence and decriminalisation had countless positive effects both for working people in general and men who desired other men specifically, the thesis will acknowledge that this impact irrevocably altered a way of life and of understanding the world.