Stanley Mosk: a Federalist for the 1980'S Arthur J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recycling the Old Circuit System

South Carolina Law Review Volume 27 Issue 4 Article 5 2-1976 Recycling the Old Circuit System Stanley Mosk Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mosk, Stanley (1976) "Recycling the Old Circuit System," South Carolina Law Review: Vol. 27 : Iss. 4 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr/vol27/iss4/5 This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mosk: Recycling the Old Circuit System RECYCLING THE OLD CIRCUIT SYSTEM STANLEY MOSK* I. INTRODUCTION To paraphrase Winston Churchill's characterization of de- mocracy: our judicial system is not a very good one, but it hap- pens to be the best there is. Nevertheless, on a theory that justice, like chastity, must be an absolute, courts constantly receive an abundance of censure from a wide assortment of sources. Today the criticism of the judiciary, though couched in a variety of terms, is often bottomed on a theme that appellate judges in their ivory towers at both state and federal levels, fail to comprehend the daily agonies of contemporary society as reflected in trial court proceedings. In the 1930's President Roosevelt and a liberal coalition railed against the Supreme Court for invalidating early New Deal legislation. The "nine old men," they said, were out of touch with the desperate needs of a society struggling to avoid economic disaster. -

Spring / Summer 2003 Newsletter

THE CALIFORNIA SUPREME COURT Historical Society_ NEWSLETTER S PRI NG/SU MM E R 200} A Trailblazer: Reflections on the Character and r l fo und Justice Lillie they Career efJu stice Mildred Lillie tended to stay until retire ment. O n e of her fo rmer BY H ON. EARL JOH NSON, JR. judicial attorneys, Ann O ustad, was with her over Legal giant. Legend. Institution. 17'ailblazer. two decades before retiring. These are the words the media - and the sources Linda Beder had been with they quoted - have used to describe Presiding Justice her over sixteen years and Mildred Lillie and her record-setting fifty-five year Pamela McCallum fo r ten career as a judge and forty-four years as a Justice on the when Justice Lillie passed California Court of Appeal. Those superlatives are all away. Connie Sullivan was absolutely accurate and richly deserved. l_ _j h er judicial ass istant for I write from a different perspective, however - as a some eighteen years before retiring and O lga Hayek colleague of Justice Lillie for the entire eighteen years served in that role for over a decade before retiring, she was Presiding Justice of Division Seven. I hope to too. For the many lawyers who saw her only in the provide some sense of what it was like to work with a courtroom, Justice Lillie could be an imposing, even recognized giant, a legend, an institution, a trailblazer. intimidating figure. But within the Division she was Readers will be disappointed if they are expecting neither intimidating nor autocratic. -

California Legal History | 2009: Vol. 4

Volume 4: 2009 California Legal History Journal of the California Supreme Court Historical Society California Legal History Volume 4 2009 Journal of the California Supreme Court Historical Society ii California Legal History is published annually by the California Supreme Court Historical Society, a non-profit corporation dedicated to recovering, preserving, and promoting California’s legal and judicial history, with particular emphasis on the California Supreme Court. SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: Membership in the Society is open to individuals at the rate of $50 or more per year, which includes the journal as a member benefit. For individual membership, please visit www.cschs.org, or contact the Society at (800) 353-7357 or 4747 North First Street, Fresno, CA 93726. Libraries may subscribe at the same rate through William S. Hein & Co. Please visit http://www.wshein.com or telephone (800) 828-7571. Back issues are available to individuals and libraries through William S. Hein & Co. at http://www.wshein.com or (800) 828-7571. Please note that issues prior to 2006 were published as California Supreme Court Historical Society Yearbook. (4 vols., 1994 to 1998-1999). SUBMIssION INFORMATION: Submissions of articles and book reviews are welcome on any aspect of California legal history, broadly construed. Unsolicited manuscripts are welcome as are prior inquiries. Submissions are reviewed by independent scholarly referees. In recognition of the hybrid nature of legal history, manuscripts will be accepted in both standard legal style (Bluebook) or standard academic style (Chicago Manu- al). Citations of cases and law review articles should generally be in Bluebook style. Manuscripts should be sent by email as MS Word or WordPerfect files. -

CA Capital Murder Cases That Are Scotus Cleared

Criminal Justice Legal Foundation Case summaries of California capital murderers with exhausted appeals CALIFORNIA CAPITAL MURDER CASES THAT ARE “SCOTUS CLEARED” As of December 6, 2016 Name Sentence Date Crime Trial Stevie Fields 35 Cal.3d 329 (1983) 8/21/79 Los Angeles Los Angeles Albert Brown 6 Cal.4th 322 (1993) 2/22/82 Riverside Riverside Fernando Belmontes 45 Cal.3d 744 (1988) 10/5/82 San Joaquin San Joaquin Kevin Cooper 53 Cal.3d 771 (1991) 5/15/85 San Bernardino San Diego Tiequon Cox 53 Cal.3d 618 (1991) 5/7/86 Los Angeles Los Angeles Royal Hayes Stanislaus 21 Cal.4th 1211 (1999) 8/8/86 Santa Cruz (penalty retrial) Harvey Heishman 45 Cal.3d 147 (1988) 3/30/81 Alameda Alameda Michael Morales 48 Cal.3d 527 (1989) 6/14/83 San Joaquin Ventura Scott Pinholster 1 Cal.4th 865 (1992) 6/14/84 Los Angeles Los Angeles Douglas Mickey 54 Cal.3d 612 (1991) 9/23/83 Placer San Mateo Mitchell Sims 5 Cal.4th 405 (1993) 9/11/87 Los Angeles Los Angeles David Raley 2 Cal.4th 870 (1992) 5/17/88 San Mateo Santa Clara Richard Gonzales Samayoa 15 Cal.4th 795 (1997) 6/28/88 San Diego San Diego Robert Fairbank 16 Cal.4th 1223 (1997) 9/5/89 San Mateo San Mateo William Charles Payton 3 Cal.4th 1050 (1992) 3/5/82 Orange County Orange County Albert Cunningham Jr. 25 Cal.4th 926 (2001) 6/16/89 Los Angeles Los Angeles Anthony John Sully 53 Cal.3d 1195 (1991) 7/15/86 San Mateo San Mateo Ronald Lee Deere 53 Cal.3d 705 (1991) 7/18/86 Riverside Riverside Hector Juan Ayala 24 Cal.4th 243 (2000) 11/30/89 San Diego San Diego Case summaries of California capital murderers with exhausted appeals Inmate: Stevie Fields 35 Cal.3d 329 (1983) Date Sentenced: 8/21/79 | Crime and Trial: Los Angeles Stevie Fields was paroled from prison on September 13, 1978, after serving a sentence for manslaughter for bludgeoning a man to death with a barbell. -

(213) 362-7788 Todd Cavanaugh Is a Civil Litigator and Trial Attorney with Expertise in Product Liability, Toxic Tort, and Business Litigation

TODD A. CAVANAUGH, PARTNER Office: Los Angeles [email protected] (213) 362-7777 220 (213) 362-7788 Todd Cavanaugh is a civil litigator and trial attorney with expertise in product liability, toxic tort, and business litigation. Licensed to practice in California, Nevada, and Washington, his experience includes all aspects of litigation, from administrative proceedings to mediation to trials and appeals. For more than 15 years, he has defended the interests of manufacturers and excess insurers in cases venued in state and federal courts in more than a dozen states. In product liability litigation, Mr. Cavanaugh has defended the design, manufacture, and performance of a diverse array of products made by some of the world's largest manufacturers. These products include automobiles, construction equipment, tires, automotive friction products, industrial machinery, and power generators. He also coordinated and executed a nationwide product liability resolution program for a major automobile manufacturer. Mr. Cavanaugh has achieved Martindale-Hubbell's highest AV rating, and has been recognized by Law & Politics as a 2014–2018 Southern California Super Lawyer. He has lectured on topics including jury selection, principles of contribution and indemnity, and strategies for overcoming the threat of joint liability. His publications include “Tumble v. Cascade Bicycle Corp.: A Hypothetical Case Under the Restatement (Third) of Torts,” published in the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform. Mr. Cavanaugh was born and raised in Minnesota, and earned a bachelor's degree in journalism from the University of Wisconsin in 1990. In 1995, he graduated summa cum laude from William Mitchell College of Law in St. -

Press Release

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA PRESS RELEASE Release Date: December 21, 2020 SENATE CONFIRMS SUPERIOR COURT JUDGE FERNANDO L. AENLLE-ROCHA AS UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE FOR THE CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA On December 20, 2020, the United States Senate confirmed President Donald J. Trump’s nomination of Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Fernando L. Aenlle-Rocha to serve as a federal district judge for the United States District Court for the Central District of California. Judge Aenlle-Rocha will preside over matters in Los Angeles in the Court’s Western Division. Judge Aenlle-Rocha has served as a Superior Court Judge for Los Angeles County since his appointment by Governor Jerry Brown in 2017. Judge Aenlle-Rocha has presided over criminal and civil matters, including over 50 trials. He most recently presided over a civil independent calendar court at the Stanley Mosk Courthouse. He also served on several Court Committees— Ethics, Diversity, Community Outreach, and Civil and Small Claims – and on the California Judges Association Civil Law Committee. Prior to his appointment as a Superior Court Judge, from 2005 to 2017, Judge Aenlle-Rocha worked as a partner at White & Case LLP where he focused on business litigation and white-collar criminal defense. Judge Aenlle-Rocha’s civil litigation practice included a variety of cases in state and federal courts. As part of his white-collar practice, Judge Aenlle-Rocha conducted internal investigations on behalf of corporate clients, provided anti-corruption compliance counsel to companies, and represented individuals and companies who were witnesses, subjects, targets, or defendants in criminal and civil enforcement proceedings. -

In the Supreme Court of the State of California

No. S______ (Court of Appeal No. C087071) (Sacramento County Super. Ct. No. JCCP 4853) IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA PACIFIC GAS AND ELECTRIC COMPANY, Petitioner, v. SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA FOR THE COUNTY OF SACRAMENTO, Respondent, ABAAN ABU-SHUMAYS et al., Real Parties in Interest . From an Order Summarily Denying a Petition for a Writ of Mandate, Prohibition, or Other Appropriate Relief, by the Court of Appeal, Third Appellate District Case No. C087071 PETITION FOR REVIEW KENNETH R. CHIATE (S.B. No. 039554) *KATHLEEN M. SULLIVAN (S.B. No. 242261) KRISTEN BIRD (S.B. No. 192863) DANIEL H. BROMBERG (S.B. No. 242659) JEFFREY N. BOOZELL (S.B. No. 199507) QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART & SULLIVAN LLP QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART & SULLIVAN LLP 555 Twin Dolphin Drive, 5th Floor 865 South Figueroa Street, 10th Floor Redwood Shores, CA 94065 Los Angeles, California 90017 Telephone: (650) 801-5000 Telephone: (213) 443-3000 Facsimile: (650) 801-5100 Facsimile: (213) 443-3100 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for Petitioner Pacific Gas and Electric Company TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .............................................................................................. 4 ISSUE PRESENTED .......................................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ -

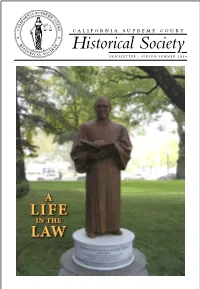

Highlights from a New Biography of Justice Stanley Mosk by Jacqueline R

California Supreme Court Historical Society newsletter · s p r i n g / summer 2014 A Life in The LAw The Longest-Serving Justice Highlights from a New Biography of Justice Stanley Mosk By Jacqueline R. Braitman and Gerald F. Uelmen* undreds of mourners came to Los Angeles’ future allies. With rare exceptions, Mosk maintained majestic Wilshire Boulevard Temple in June of cordial relations with political opponents throughout H2001. The massive, Byzantine-style structure his lengthy career. and its hundred-foot-wide dome tower over the bustling On one of his final days in office, Olson called Mosk mid-city corridor leading to the downtown hub of finan- into his office and told him to prepare commissions to cial and corporate skyscrapers. Built in 1929, the historic appoint Harold Jeffries, Harold Landreth, and Dwight synagogue symbolizes the burgeoning pre–Depression Stephenson to the Superior Court, and Eugene Fay and prominence and wealth of the region’s Mosk himself to the Municipal Court. Jewish Reform congregants, includ- Mosk thanked the governor profusely. ing Hollywood moguls and business The commissions were prepared and leaders. Filing into the rows of seats in the governor signed them, but by then the cavernous sanctuary were two gen- it was too late to file them. The secre- erations of movers and shakers of post- tary of state’s office was closed, so Mosk World War II California politics, who locked the commissions in his desk and helped to shape the course of history. went home, intending to file them early Sitting among less recognizable faces the next morning. -

Oral History Interview with Honorable Stanley Mosk

California State Archives State Government Oral History Program Oral History Interview with HONORABLE STANLEY MOSK Justice of the California Supreme Court, 1964-present February 18, March 11, April 2, May 27, July 22, 1998 San Francisco, California By Germaine LaBerge Regional Oral History Office University of California, Berkeley RESTRICTIONS ON THIS INTERVIEW None. LITERARY RIGHTS AND QUOTATIONS This manuscript is hereby made available for research purposes only. No part of this manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the California State Archivist or the Regional Oral History Office, University of California at Berkeley. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to: California State Archives 1020 0 Street, Room 130 Sacramento, California 95814 or Regional Oral History Office 486 The Bancroft Library University of California Berkeley, California 94720 The request should include information of the specific passages and identification of the user. It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows: Honorable Stanley Mosk Oral History Interview, Conducted 1998 by Germaine LaBerge, Regional Oral History Office, University of California at Berkeley, for the California State Archives State Government Oral History Program. INTERVIEW HISTORY InterviewerlEditor: Germaine LaBerge Editor, University of California at Berkeley State Archives State Government Oral History Program B.A. Manhattanville College, Purchase, New York (History) M.A. Mary Grove College, Detroit, Michigan (Education) Member (inactive), California State Bar Interview Time and Place: February 18, 1998, Session of one and a half hours. March 11, 1998, Session of one and a half hours. April 2, 1998, Session of one hour. May 27, 1998, Session of one hour. -

Lasc Announces Small Claims Cases to Be Heard in Every Judicial District

Los Angeles Superior Court – Public Information Office 111 N. Hill Street, Room 107, Los Angeles, CA 90012 [email protected] www.lacourt.org NOTICE TO PUBLIC October 13, 2017 LASC ANNOUNCES SMALL CLAIMS CASES TO BE HEARD IN EVERY JUDICIAL DISTRICT Effective Oct. 10, 2017, the Los Angeles Superior Court will expand small claims operations from six to eleven courthouses, as follows: • Chatsworth Courthouse, 9425 Penfield Ave., Chatsworth 91311 (New) • Compton Courthouse, 200 West Compton Blvd., Compton 90220 (New) • Governor George Deukmejian (Long Beach) Courthouse, 275 Magnolia, Long Beach 90802 (New) • Pasadena Courthouse, 300 East Walnut, Pasadena, 91101 (New) (Effective Oct. 10, 2017, small claims cases will no longer be heard at the Alhambra Courthouse.) • Santa Monica Courthouse, 1725 Main St., Santa Monica, 90401 (New) • West Covina Courthouse, 1427 West Covina Parkway, West Covina, 91790 (New) • Downey Courthouse, 7500 East Imperial Highway, Downey, 90242 • Inglewood Courthouse, One Regent Street, Inglewood, 90301 • Michael D. Antonovich (Antelope Valley) Courthouse, 42011 Fourth Street West, Lancaster, 93534 • Stanley Mosk Courthouse, 111 North Hill Street, Los Angeles, 90012 • Van Nuys East Courthouse, 6230 Sylmar Ave., Van Nuys, 91401 LASC Local Rule 2.3(a)(2) specifies small claims cases must be filed in the courthouse serving the location and proper United States Postal Service zip code of the property in dispute using the Zip Code Table for Small Claims cases. The zip code table is available on the Court’s website at: http://www.lacourt.org/filinglocatornet/ui/filingsearch.aspx, on the home page and on the Small Claims and Civil Division pages. A copy of the Zip Code Table for Small Claims cases will also be available in every courthouse to assist parties in determining the new filing locations. -

The California Recall History Is a Chronological Listing of Every

Complete List of Recall Attempts This is a chronological listing of every attempted recall of an elected state official in California. For the purposes of this history, a recall attempt is defined as a Notice of Intention to recall an official that is filed with the Secretary of State’s Office. 1913 Senator Marshall Black, 28th Senate District (Santa Clara County) Qualified for the ballot, recall succeeded Vote percentages not available Herbert C. Jones elected successor Senator Edwin E. Grant, 19th Senate District (San Francisco County) Failed to qualify for the ballot 1914 Senator Edwin E. Grant, 19th Senate District (San Francisco County) Qualified for the ballot, recall succeeded Vote percentages not available Edwin I. Wolfe elected successor Senator James C. Owens, 9th Senate District (Marin and Contra Costa counties) Qualified for the ballot, officer retained 1916 Assemblyman Frank Finley Merriam Failed to qualify for the ballot 1939 Governor Culbert L. Olson Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Citizens Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot 1940 Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot 1960 Governor Edmund G. Brown Filed by Roderick J. Wilson Failed to qualify for the ballot 1 Complete List of Recall Attempts 1965 Assemblyman William F. Stanton, 25th Assembly District (Santa Clara County) Filed by Jerome J. Ducote Failed to qualify for the ballot Assemblyman John Burton, 20th Assembly District (San Francisco County) Filed by John Carney Failed to qualify for the ballot Assemblyman Willie L. -

Congressional Record—House H3927

July 11, 2001 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H3927 Kelly Nadler Sherman RESIGNATION AS MEMBER OF CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES, Kennedy (MN) Napolitano Sherwood COMMITTEE ON STANDARDS OF HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, Kennedy (RI) Neal Shimkus July 11, 2001. Kerns Nethercutt Shows OFFICIAL CONDUCT Hon. J. DENNIS HASTERT, Kildee Ney Shuster The SPEAKER pro tempore (Mr. Kilpatrick Northup Simmons Speaker, U.S. House of Representatives, Kind (WI) Norwood Simpson SIMPSON) laid before the House the fol- Washington, DC. King (NY) Nussle Skeen lowing resignation as a member of the DEAR MR. SPEAKER: This is to formally no- Kingston Oberstar Skelton Committee on Standards of Official tify you, pursuant to Rule VIII of the Rules Slaughter Kirk Obey Conduct. of the House of Representatives, that my of- Kleczka Olver Smith (MI) fice has been served with a civil subpoena for Smith (NJ) CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES, Knollenberg Ortiz documents issued by the Superior Court for Kolbe Osborne Smith (TX) HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, Smith (WA) Washington, DC, June 29, 2001. Allen County, Indiana in a civil case pending Kucinich Ose there. LaFalce Otter Snyder Hon. J. DENNIS HASTERT, LaHood Owens Solis Speaker, House of Representatives, Washington, After consultation with the Office of Gen- Souder Lampson Oxley eral Counsel, I have determined that it is Spence DC. Langevin Pallone consistent with the precedents and privileges Spratt DEAR MR. SPEAKER: I am writing to submit Lantos Pascrell of the House to advise the party who issued Stearns my resignation from the Committee on Largent Pastor Stenholm Standards of Official Conduct. the subpoena that I have no documents that Larsen (WA) Payne Strickland I will consider my resignation effective im- are responsive to the subpoena.