The Poetics of Baseball: an American Domestication of the Mathematically Sublime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CHAPTER 1 Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed King Arthur’s quest for it in the Middle Ages became a large part of his legend. Monty Python and Indiana Jones launched their searches in popular 1974 and 1989 movies. The mythic quest for the Holy Grail, the name given in Western tradition to the chal- ice used by Jesus Christ at his Passover meal the night before his death, is now often a metaphor for a quintessential search. In the illustrious history of baseball, the “holy grail” is a ranking of each player’s overall value on the baseball diamond. Because player skills are multifaceted, it is not clear that such a ranking is possible. In comparing two players, you see that one hits home runs much better, whereas the other gets on base more often, is faster on the base paths, and is a better fielder. So which player should rank higher? In Baseball’s All-Time Best Hitters, I identified which players were best at getting a hit in a given at-bat, calling them the best hitters. Many reviewers either disapproved of or failed to note my definition of “best hitter.” Although frequently used in base- ball writings, the terms “good hitter” or best hitter are rarely defined. In a July 1997 Sports Illustrated article, Tom Verducci called Tony Gwynn “the best hitter since Ted Williams” while considering only batting average. -

AROUND the HORN News & Notes from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum September Edition

NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM, INC. 25 Main Street, Cooperstown, NY 13326-0590 Phone: (607) 547-0215 Fax: (607)547-2044 Website Address – baseballhall.org E-Mail – [email protected] NEWS Brad Horn, Vice President, Communications & Education Craig Muder, Director, Communications Matt Kelly, Communications Specialist P R E S E R V I N G H ISTORY . H O N O R I N G E XCELLENCE . C O N N E C T I N G G ENERATIONS . AROUND THE HORN News & Notes from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum September Edition Sept. 17, 2015 volume 22, issue 8 FRICK AWARD BALLOT VOTING UNDER WAY The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s Ford C. Frick Award is presented annually since 1978 by the Museum for excellence in baseball broadcasting…Annual winners are announced as part of the Baseball Winter Meetings each year, while awardees are presented with their honor the following summer during Hall of Fame Weekend in Cooperstown, New York…Following changes to the voting regulations implemented by the Hall of Fame’s Board of Directors in the summer of 2013, the selection process reflects an era-committee system where eligible candidates are grouped together by years of most significant contributions of their broadcasting careers… The totality of each candidate’s career will be considered, though the era in which the broadcaster is deemed to have had the most significant impact will be determined by a Hall of Fame research team…The three cycles reflect eras of major transformations in broadcasting and media: The “Broadcasting Dawn Era” – to be voted on this fall, announced in December at the Winter Meetings and presented at the Hall of Fame Awards Presentation in 2016 – will consider candidates who contributed to the early days of baseball broadcasting, from its origins through the early-1950s. -

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox Jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds Jersey MLB

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds jersey MLB Wade Boggs Red Sox jersey MLB Johnny Damon Red Sox jersey MLB Goose Gossage Yankees jersey MLB Dwight Goodin Mets jersey MLB Adam LaRoche Pirates jersey MLB Jose Conseco jersey MLB Jeff Montgomery Royals jersey MLB Ned Yost Royals jersey MLB Don Larson Yankees jersey MLB Bruce Sutter Cardinals jersey MLB Salvador Perez All Star Royals jersey MLB Bubba Starling Royals baseball bat MLB Salvador Perez Royals 8x10 framed photo MLB Rolly Fingers 8x10 framed photo MLB Joe Garagiola Cardinals 8x10 framed photo MLB George Kell framed plaque MLB Salvador Perez bobblehead MLB Bob Horner helmet MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Frank White and Willie Wilson framed photo MLB Salvador Perez 2015 Royals World Series poster MLB Bobby Richardson baseball MLB Amos Otis baseball MLB Mel Stottlemyre baseball MLB Rod Gardenhire baseball MLB Steve Garvey baseball MLB Mike Moustakas baseball MLB Heath Bell baseball MLB Danny Duffy baseball MLB Frank White baseball MLB Jack Morris baseball MLB Pete Rose baseball MLB Steve Busby baseball MLB Billy Shantz baseball MLB Carl Erskine baseball MLB Johnny Bench baseball MLB Ned Yost baseball MLB Adam LaRoche baseball MLB Jeff Montgomery baseball MLB Tony Kubek baseball MLB Ralph Terry baseball MLB Cookie Rojas baseball MLB Whitey Ford baseball MLB Andy Pettitte baseball MLB Jorge Posada baseball MLB Garrett Cole baseball MLB Kyle McRae baseball MLB Carlton Fisk baseball MLB Bret Saberhagen baseball -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

2019 Topps Series 1 Checklist

BASE VETERANS 1 Ronald Acuña Jr. Atlanta Braves™ Rookie Cup 2 Tyler Anderson Colorado Rockies™ 3 Eduardo Nunez Boston Red Sox® World Series Highlights 4 Dereck Rodriguez San Francisco Giants® Future Stars 5 Chase Anderson Milwaukee Brewers™ 6 Max Scherzer Washington Nationals® League Leaders 7 Gleyber Torres New York Yankees® Rookie Cup 8 Adam Jones Baltimore Orioles® 9 Ben Zobrist Chicago Cubs® 10 Clayton Kershaw Los Angeles Dodgers® 11 Mike Zunino Seattle Mariners™ 12 Crackin' Jokes Major League Baseball® 13 David Price Boston Red Sox® 14 The Yankees® Win! New York Yankees® 15 J.P. Crawford Philadelphia Phillies® 16 Charlie Blackmon Colorado Rockies™ 17 Caleb Joseph Baltimore Orioles® 18 Blake Parker Angels® 19 Jacob deGrom New York Mets® League Leaders 20 Jose Urena Miami Marlins® 21 Jean Segura Seattle Mariners™ 22 Adalberto Mondesi Kansas City Royals® 23 J.D. Martinez Boston Red Sox® League Leaders 24 Blake Snell Tampa Bay Rays™ League Leaders 25 Chad Green New York Yankees® 26 Angel Stadium™ Angels® 27 Mike Leake Seattle Mariners™ 28 Boston's Boys Boston Red Sox® 29 Eugenio Suarez Cincinnati Reds® 30 Josh Hader Milwaukee Brewers™ 31 Busch Stadium™ St. Louis Cardinals® 32 Carlos Correa Houston Astros® 33 Jacob Nix San Diego Padres™ Rookie 34 Josh Donaldson Cleveland Indians® 35 Joey Rickard Baltimore Orioles® 36 Paul Blackburn Oakland Athletics™ 37 Marcus Stroman Toronto Blue Jays® 38 Kolby Allard Atlanta Braves™ Rookie 39 Richard Urena Toronto Blue Jays® 40 Jon Lester Chicago Cubs® 41 Corey Seager Los Angeles Dodgers® 42 Edwin Encarnacion Cleveland Indians® 43 Nick Burdi Pittsburgh Pirates® Rookie 44 Jay Bruce New York Mets® 45 Nick Pivetta Philadelphia Phillies® 46 Jose Abreu Chicago White Sox® 47 Yankee Stadium™ New York Yankees® 48 PNC Park™ Pittsburgh Pirates® 49 Michael Kopech Chicago White Sox® Rookie 50 Mookie Betts Boston Red Sox® 51 Michael Brantley Cleveland Indians® 52 J.T. -

San Francisco Giants Homestand Release | September 29 – October 1, 2017

San Francisco Giants Homestand Release | September 29 – October 1, 2017 Sept. 29 – Oct. 1 vs. San Diego Padres sfgiants.com • sfgigantes.com • twitter/SFGiants • facebook/Giants • instagram/sfgiants • snapchat/sfgiants HOMESTAND HIGHLIGHTED BY MATT CAIN RETIREMENT, WILLIE MAC AWARD, FAN APPRECIATION DAY, OKTOBERFEST AND STAR WARS® DAY FRI., SEPT 29 | 7:15 P.M. | SAN DIEGO PADRES GIVEAWAY – BB-8 BEANIE – Presented by PG&E – First BROADCASTS: KNBR 680AM, SPANISH RADIO KXZM 93.7FM, NBC 20,000 fans SPORTS BAY AREA PROMOTION – FAN APPRECIATION MONTH: To NATIONAL ANTHEM: Jordyn Diew celebrate Fan Appreciation CEREMONIAL FIRST PITCH: Presented by Konica Minolta Month, the Giants will give out prizes during each home game to lucky PROMOTION – FAN APPRECIATION MONTH: fans. Prizes include Star Wars VIP screening, To celebrate Fan Appreciation Month, the $100 Jack in the Box Cash Card, $50 Giants will give out prizes during each home Chevron Gas Card and more. game to lucky fans. Prizes include Silver Oak Wine Tour & Tasting, Steal 2nd Base SPECIAL PROMOTION – SF/MARIN FOOD BANK FOOD DRIVE: experience, Altec Lansing Bluetooth Presented by Visa: First 3,000 fans who donate $5 or 5 cans of food headphones and more. will receive a Giants drawstring bag. SPECIAL PRE-GAME CEREMONY – WILLIE MAC AWARD: Each year the SPECIAL EVENT – STAR WARS® DAY: The Giants will Willie Mac Award is given to a Giants player who best exemplifies the host the annual STAR WARS® day at AT&T Park. This inspiration, character and leadership that Willie McCovey special event ticket includes a Giants-themed BB-8 demonstrated during his playing days in San Francisco. -

Kit Young's Sale

KIT YOUNG’S SALE #91 1952 ROYAL STARS OF BASEBALL DESSERT PREMIUMS These very scarce 5” x 7” black & white cards were issued as a premium by Royal Desserts in 1952. Each card includes the inscription “To a Royal Fan” along with the player’s facsimile autograph. These are rarely offered and in pretty nice shape. Ewell Blackwell Lou Brissie Al Dark Dom DiMaggio Ferris Fain George Kell Reds Indians Giants Red Sox A’s Tigers EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX EX+ EX+/EX-MT EX+ $55.00 $55.00 $39.00 $120.00 $55.00 $99.00 Stan Musial Andy Pafko Pee Wee Reese Phil Rizzuto Eddie Robinson Ray Scarborough Cardinals Dodgers Dodgers Yankees White Sox Red Sox EX+ EX+ EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT $265.00 $55.00 $175.00 $160.00 $55.00 $55.00 1939-46 SALUTATION EXHIBITS Andy Seminick Dick Sisler Reds Reds EX-MT EX+/EX-MT $55.00 $55.00 We picked up a new grouping of this affordable set. Bob Johnson A’s .................................EX-MT 36.00 Joe Kuhel White Sox ...........................EX-MT 19.95 Luke Appling White Sox (copyright left) .........EX-MT Ernie Lombardi Reds ................................. EX 19.00 $18.00 Marty Marion Cardinals (Exhibit left) .......... EX 11.00 Luke Appling White Sox (copyright right) ........VG-EX Johnny Mize Cardinals (U.S.A. left) ......EX-MT 35.00 19.00 Buck Newsom Tigers ..........................EX-MT 15.00 Lou Boudreau Indians .........................EX-MT 24.00 Howie Pollet Cardinals (U.S.A. right) ............ VG 4.00 Joe DiMaggio Yankees ........................... -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

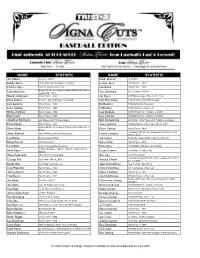

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

Sports Figures Price Guide

SPORTS FIGURES PRICE GUIDE All values listed are for Mint (white jersey) .......... 16.00- David Ortiz (white jersey). 22.00- Ching-Ming Wang ........ 15 Tracy McGrady (white jrsy) 12.00- Lamar Odom (purple jersey) 16.00 Patrick Ewing .......... $12 (blue jersey) .......... 110.00 figures still in the packaging. The Jim Thome (Phillies jersey) 12.00 (gray jersey). 40.00+ Kevin Youkilis (white jersey) 22 (blue jersey) ........... 22.00- (yellow jersey) ......... 25.00 (Blue Uniform) ......... $25 (blue jersey, snow). 350.00 package must have four perfect (Indians jersey) ........ 25.00 Scott Rolen (white jersey) .. 12.00 (grey jersey) ............ 20 Dirk Nowitzki (blue jersey) 15.00- Shaquille O’Neal (red jersey) 12.00 Spud Webb ............ $12 Stephen Davis (white jersey) 20.00 corners and the blister bubble 2003 SERIES 7 (gray jersey). 18.00 Barry Zito (white jersey) ..... .10 (white jersey) .......... 25.00- (black jersey) .......... 22.00 Larry Bird ............. $15 (70th Anniversary jersey) 75.00 cannot be creased, dented, or Jim Edmonds (Angels jersey) 20.00 2005 SERIES 13 (grey jersey ............... .12 Shaquille O’Neal (yellow jrsy) 15.00 2005 SERIES 9 Julius Erving ........... $15 Jeff Garcia damaged in any way. Troy Glaus (white sleeves) . 10.00 Moises Alou (Giants jersey) 15.00 MCFARLANE MLB 21 (purple jersey) ......... 25.00 Kobe Bryant (yellow jersey) 14.00 Elgin Baylor ............ $15 (white jsy/no stripe shoes) 15.00 (red sleeves) .......... 80.00+ Randy Johnson (Yankees jsy) 17.00 Jorge Posada NY Yankees $15.00 John Stockton (white jersey) 12.00 (purple jersey) ......... 30.00 George Gervin .......... $15 (whte jsy/ed stripe shoes) 22.00 Randy Johnson (white jersey) 10.00 Pedro Martinez (Mets jersey) 12.00 Daisuke Matsuzaka .... -

Lugnuts Media Guide & Record Book

Lugnuts Media Guide & Record Book Table of Contents Lugnuts Media Guide Staff Directory ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Executive Profiles ............................................................................................................................................................................................................4 The Midwest League Midwest League Map and Affiliation History .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Bowling Green Hot Rods / Dayton Dragons ................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Fort Wayne TinCaps / Great Lakes Loons ...................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Lake County Captains / South Bend Cubs ...................................................................................................................................................................... 9 West Michigan Whitecaps ............................................................................................................................................................................................ -

The 3-6-3 Double Play

The 3-6-3 Double Play By Christopher Chestnut January 5, 2010 E-mail: [email protected] Purpose The purpose of this study is to determine which major league first baseman turned the most 3-6-3 double plays. Data Sources The information used in this study was obtained free of charge from and is copyrighted by Retrosheet. Interested parties may contact Retrosheet at www.retrosheet.org. Definitions 3-6-3 Double Play – the first baseman fields a ground ball and throws to the shortstop to retire the runner on first. The shortstop returns the throw to the first baseman to retire the batter/runner. Opportunity – all ground balls (including bunts, excluding base hits) fielded by the first baseman with a runner on first (additional runners may be on second and/or third) and less than two outs. Attempt – all opportunities where the first play by the first baseman is a throw to the shortstop. Methodology I used play-by-play data from Retrosheet to support my analysis. The available data includes the American and National Leagues for 1952-2009. I processed the data for each season to generate a list of all players with at least one opportunity in any one of these eight situations: No outs, runner on first No outs, runners on first and second No outs, runners on first and third No outs, bases full One out, runner on first One out, runners on first and second One out, runners on first and third One out, bases full 1 of 7 The 3-6-3 Double Play January 5, 2010 Results Filtering out the non-ground balls and base hits, I found: 1,319 players