Download Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yamuna Does Not Belong to Haryana... We’Re Working on Contingencies’ the Hindu

2/29/2016 ‘Yamuna does not belong to Haryana... we’re working on contingencies’ The Hindu CITIES » DELHI Published: February 29, 2016 00:00 IST | Updated: February 29, 2016 05:34 IST February 29, 2016 ‘Yamuna does not belong to Haryana... we’re working on contingencies’ We are looking at interlinking our water treatment plants, says DJB chief Kapil Mishra.Photo: Sushil Kumar Verma Delhi Jal Board chairperson Kapil Mishra speaks to Damini Nath about some initiatives that the Delhi government is considering in case the Capital faces a water crisis again. You've said earlier that Delhi depends on the Yamuna for water, not Haryana. But, the recent agitation in Haryana hit Delhi's water supply. Doesn't this show the dependence on Haryana? The river does not belong to Haryana. The river is for all of us. And Haryana too gets water from Punjab. The water that Delhi gets from Haryana is as per certain guidelines, treaties and even a Supreme Court order. Haryana is bound by the guidelines to share water with Delhi. Given how the Jat protests led to a shutdown of seven DJB plants, are you planning on any emergency measures in the future so the crisis is not repeated? We cannot replace the river. Delhi is the Capital of the country because the Yamuna flows through it. We need the Yamuna, but we should also have a week to 10 days’ worth of water supply of our own in case of emergencies. The Delhi Jal Board (DJB) is working on a plan that will be ready soon. -

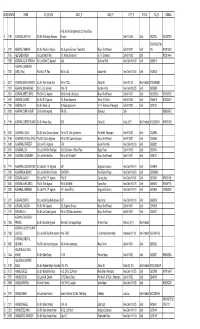

Child Welfare Committees (Chairperson & Members) 16-06-2016

List of Child Welfare Committees (Chairperson & Members) 16-06-2016 S. CHILD WELFARE CHAIRPERSON NAME , RESIDENCE & No. COMMITTEE PHONE No. & MEMBERS 1 2 3 4 1. Child Welfare Smt. Rachna Srivastava Chairperson Committee-I, D-IV/2, Rites Flats, Ashok Vihar-III, Delhi. Nirmal Chhaya Complex, Mobile No. 9968169941 Jail Road, Delhi Smt. Malashri S. Malik Member 401, Air Lines Apartment, 011-28546733 Plot No. 5, Sector – 23, Dwarka, New [email protected] Delhi,Mob.9910209866 Sh. Sunil Kumar Member Plot No. 81, Flat No. 10, Vikram Enclave, Martin Apartment, Extension Sahibabad, Ghaziabad, U.P. M. No. 9868396911 Ms. Paramjeet Kaur Member Pardeshi R/o B-6, Mitradweep Apartment, 38 I.P. Extension, Delhi-92,Mob.9555638383 Ms. Kavita Bhandari Member R/o H. No. 79 D, Rockview Officers Enclave, Air Force Station, Palam, Delhi Cantt- 110010,Mob.8800962458 2. Child Welfare Sh. Jas Ram Kain Chairperson Committee-II, R/o 50/1, MCD Officers Flat, Bunglow Road, Kamla Nagar, Kasturba Niketan Delhi Complex, Lajpat Nagar, M. No. 9717750214 Delhi. Smt. Renu Malhotra Member 672, Sector 37, Faridabad 011-29819329 M. No. 9654561363 Sh. Asif Iqbal Member [email protected] R/o H. No. 336, Sector-16, m Vasundhara, Ghaziabad, U.P. M. No. 8750157676 Ms. Satya Prabha Member R/o D-II/36, Shahjahan Road, New Delhi- 1,Mob.9810161339 3. Child Welfare Ms. Vimla Paul Chairperson 174, Manu Apartments, Committee-III, Mayur Vihar Phase-I, Delhi M. 9810740401 Sewa Kutir Complex, Sh. Edward Daniel Member Kingsway Camp, Delhi. Mission Compound, 13-Raj Niwas Marg, Civil 011-27652575 Lines, Delhi. -

Bird Species in Delhi-“Birdwatching” Tourism

Conference Proceedings: 2 nd International Scientific Conference ITEMA 2018 BIRD SPECIES IN DELHI-“BIRDWATCHING” TOURISM Zeba Zarin Ansari 63 Ajay Kumar 64 Anton Vorina 65 https://doi.org/10.31410/itema.2018.161 Abstract : A great poet William Wordsworth once wrote in his poem “The world is too much with us” that we do not have time to relax in woods and to see birds chirping on trees. According to him we are becoming more materialistic and forgetting the real beauty of nature. Birds are counted one of beauties of nature and indeed they are smile giver to human being. When we get tired or bored of something we seek relax to a tranquil place to overcome the tiredness. Different birds come every morning to make our day fresh. But due to drainage system, over population, cutting down of trees and many other disturbances in the metro city like Delhi, lots of species of birds are disappearing rapidly. Thus a conservation and management system need to be required to stop migration and disappearance of birds. With the government initiative and with the help of concerned NGOs and other departments we need to settle to the construction of skyscrapers. As we know bird watching tourism is increasing rapidly in the market, to make this tourism as the fastest outdoor activity in Delhi, the place will have to focus on the conservation and protection of the wetlands and forests, management of groundwater table to make a healthy ecosystem, peaceful habitats and pollution-free environment for birds. Delhi will also have to concentrate on what birdwatchers require, including their safety, infrastructure, accessibility, quality of birdlife and proper guides. -

Land Rates Laid Down in the Ministry’S Letter No

SCHEDULE OF MARKET RATES OF LAND IN DELHI – 1.4.1987 to 31.3.2000 S.No. Name of the Rates per Sq. m. Rates per Sq. m. Rates per Sq. m. Rates per Sq. m. Locality w.e.f. 1.4.98 1.4.91 to 31.3.98 1.4.89 to 31.3.91 1.4.87 to 31.3.89 Residential Commercial Residential Commercial Residential Commercial Residential Commercial Zone –I FAR-250 Central Zone 1. Connaught Place 18,480/- 57,960/- 16,800/- 50,400/- 14,000/- 42,000/- 8000/- 23,000/- 2. Connaught circus 18,480/- 57,960/- 16,800/- 50,400/- 14,000/- 42,000/- 8000/- 23,000/- 3. Connaught Place 18,480/- 57,960/- 16,800/- 50,400/- 14,000/- 42,000/- 8000/- 23,000/- Extension up to Commercial Centre 4. Barakhamba Road 18,480/- 57,960/- 16,800/- 50,400/- 14,000/- 42,000/- 8000/- 23,000/- (beyond Connaught Place Extn. Up to Commercial Zone) 5. Curzon Road (beyond 18,480/- 57,960/- 16,800/- 50,400/- 14,000/- 42,000/- 8000/- 23,000/- Connaught Place Extension up to Commercial Zone) 6. Hanuman 18,480/- 57,960/- 16,800/- 50,400/- 14,000/- 42,000/- 8000/- 23,000/- Road(Commercial Zone) 7. Janpath(beyond 18,480/- 57,960/- 16,800/- 50,400/- 14,000/- 42,000/- 8000/- 23,000/- Connaught Place Extension up to Windsor Place) 8. Bhagwandas Road 18,480/- 57,960/- 16,800/- 50,400/- 14,000/- 42,000/- 8000/- 23,000/- 9. Hailey Road 18,480/- 57,960/- 16,800/- 50,400/- 14,000/- 42,000/- 8000/- 23,000/- 10. -

An Overview on the Threats and Conservation Strategies of Wetlands

G- J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 7(1): 1-5 (2019) ISSN (Online): 2322-0228 (Print): 2322-021X G- Journal of Environmental Science and Technology www.gjestenv.com REVIEW ARTICLE The Dying Wetlands of Delhi: An Overview on the Threats and Conservation Strategies of Wetlands Kalpita Sonowal1, Pravita Kumar2, Neetu Dwivedi1, Pramod kumar2, Rohit Mondal3 1Department of Environmental Studies, Sri Aurobindo College, University of Delhi, INDIA 2Department of Chemistry, Sri Aurobindo College, University of Delhi, INDIA 3Sri Aurobindo College, University of Delhi, INDIA Received: 02 June 2019; Revised: 27 July 2019; Accepted: 24 Aug 2019 ABSTRACT India is endowed with an area of 4.3% of its total geographical area as wetlands, out of which Delhi share accounts for only 0.02% (2771 sq. km). Though wetlands comprise of only 4% of the total earth’s surface, these are the most productive ecosystems and provide a wide range of ecological services like recharging of ground water, food, raw materials, habitat for wildlife, recreational values, etc. But these fragile ecosystems are under tremendous stress due to different anthropogenic activities like developmental activities, unplanned urbanization, pollution and growth of population, particularly in metropolitan cities like Delhi. As a consequence, there has been a decline in the hydrological, economic and ecological functions provided by the wetlands. This paper concentrates on the important wetlands of Delhi and gives an account on its importance and the continuous threats they are exposed to. It also discusses the management and restoration techniques that can be deployed to retrieve these dying entities. Key words: Wetlands; fragile ecosystem; ecological services; threats; management and restoration 1) INTRODUCTION functions such as recharging ground water, attenuating Wetlands are defined as the transitional ecosystems floods, purifying water, recycling nutrients and also between the terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. -

M/S Rohan Automotive Equipment Private Ltd. B-16 Lajpat Nagar-I, New Delhi-24 Ph.29819931, 35903506 Kit Name : RAEPL-CNG-1-A1

M/s Rohan Automotive Equipment Private Ltd. B-16 Lajpat Nagar-I, New Delhi-24 Ph.29819931, 35903506 Kit Name : RAEPL-CNG-1-A1. S.No. Vehicle Model Conversion Period 1. Maruti Esteem MPFL LX & VX 01.04.2000 up to validity of B.S.II norms 2. Hyundai Santro (999cc) -do- 3. Ford (1299cc) -do- 4. Maruti Baleno (1590 cc) -do- 5. Tata Indica (1405cc) -do- 6. Maruti Wagon R Std 1061cc -do- 7. Maruti Wagon R LX -do- 8. Maruti Wagon R Lxi -do- 9. Maruti Wagon R RVX -do- 10. Maruti Wagon R RVXi -do- 11. Tata Indica (1405cc) -do- 12. Premier Padmini (1889cc) -do- 13. Maruti Zen(993cc) -do- 14. Fiat Uno (999cc) -do- 15. Maruti 800(796cc) -do- 16. Fiat Palio 1.2(1242cc) -do- 17. Fiat Sienc 1.2 (1242cc) -do- 18. Maruti Zen (993cc) -do- 19. Maruti Alto1.1 (1061cc) -do- 20. Maruti Alto (796cc) -do- 21. Maruti Omni (796cc) -do- 22. Maruti Esteem-1298cc 01.04.1996 upto validity of BS-II norms 23. Maruti Esteem LX -do- 24. Maruti Esteem Lxi -do- 25. Maruti Esteem VX -do- 26. Maruti Esteem Vxi -do- 27. Maruti Esteem Taxi -do- 28. Fiat Petrs (1596cc) -do- 29. Hyundai Accent(1596cc) -do- 30. Hyundai Accent(1495 cc) -do- 31. Opel Corsa 1.6 (1598cc)in -do- 32. Honda City 1.5(1498cc) -do- M/s Eco Gas System (I) Pvt. Ltd. Distributor: 1. Global Fuel Systems, B-2 Flat No.102 Nidhi House Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi. Ph-26184499 2. Advvantek System, 2/64 Bhim Street, Vishwas Nagar, Delhi Ph.22389548, 22393362, 51604041, 51604042 Kit Name: EGS-Esteem CNG/005 S.No. -

JOURNEY SO FAR of the River Drain Towards East Water

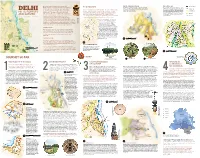

n a fast growing city, the place of nature is very DELHI WITH ITS GEOGRAPHICAL DIVISIONS DELHI MASTER PLAN 1962 THE REGION PROTECTED FOREST Ichallenging. On one hand, it forms the core framework Based on the geology and the geomorphology, the region of the city of Delhi The first ever Master plan for an Indian city after independence based on which the city develops while on the other can be broadly divided into four parts - Kohi (hills) which comprises the hills of envisioned the city with a green infrastructure of hierarchal open REGIONAL PARK Spurs of Aravalli (known as Ridge in Delhi)—the oldest fold mountains Aravalli, Bangar (main land), Khadar (sandy alluvium) along the river Yamuna spaces which were multi functional – Regional parks, Protected DELHI hand, it faces serious challenges in the realm of urban and Dabar (low lying area/ flood plains). greens, Heritage greens, and District parks and Neighborhood CULTIVATED LAND in India—and river Yamuna—a tributary of river Ganga—are two development. The research document attempts to parks. It also included the settlement of East Delhi in its purview. HILLS, FORESTS natural features which frame the triangular alluvial region. While construct a perspective to recognize the role and value Moreover the plan also suggested various conservation measures GREENBELT there was a scattering of settlements in the region, the urban and buffer zones for the protection of river Yamuna, its flood AND A RIVER of nature in making our cities more livable. On the way, settlements of Delhi developed, more profoundly, around the eleventh plains and Ridge forest. -

Status, Revival and Greening of Water Bodies in Delhi

STATUS, REVIVAL AND GREENING OF WATER BODIES IN DELHI Delhi Parks And Gardens Society, Department of Environment, Govt. of NCT of Delhi Water bodies Wetlands: All submerged or water saturated lands, natural or manmade, inland or coastal, permanent or temporary, static or dynamic, vegetated or non-vegetated, which necessarily have a land-water interface. The following waterbodies are recognized as wetlands: • oxbow lakes, riverine marshes • freshwater lakes and associated marshes (lacustrine) • freshwater ponds (under 8 ha), marshes, swamps (palustrine) • shrimp ponds, fish ponds • shallow sea bays and straits (under six meters at low tide) • estuaries, deltas • sea beaches (sand, pebbles) • intertidal mudflats, sand flats • mangrove swamps, mangrove forest • coastal brackish and saline lagoons and marshes • salt pans (artificial) • rivers, streams – slow flowing (lower perennial) • rivers, streams – fast flowing (upper perennial) • salt lakes, saline marshes (inland drainage systems) • water storage reservoirs, dams • seasonally flooded grassland, savanna, palm savanna • rice paddies • flooded arable land, irrigated land • swamp forest, temporarily flooded forest • peat bogs • In the context of Delhi water bodies are to be defined as “Bodies of still waters in the urbanscape or ruralscape which are either naturally present or intentionally created” ( In a meeting 5th February, 2002 Commissioner, MCD of the several concerned govt. agencies in Delhi) • Areas of unintentional water logging along railway tracks, canals, highways are excluded”. Delhi Parks And Gardens Society, Department of Environment, Govt. of NCT of Delhi Nature of Water bodies in Delhi Village Ponds:- Most of the water bodies are Village Ponds located in the revenue area of villages. The village ponds are mostly created water bodies having very small localized catchments for gathering rainwater. -

Main Voter List 08.01.2018.Pdf

Sl.NO ADM.NO NAME SO_DO_WO ADD1_R ADD2_R CITY_R STATE TEL_R MOBILE 61-B, Abul Fazal Apartments 22, Vasundhara 1 1150 ACHARJEE,AMITAVA S/o Shri Sudhamay Acharjee Enclave Delhi-110 096 Delhi 22620723 9312282751 22752142,22794 2 0181 ADHYARU,YASHANK S/o Shri Pravin K. Adhyaru 295, Supreme Enclave, Tower No.3, Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 745 9810813583 3 0155 AELTEMESH REIN S/o Late Shri M. Rein 107, Natraj Apartments 67, I.P. Extension Delhi-110 092 Delhi 9810214464 4 1298 AGARWAL,ALOK KRISHNA S/o Late Shri K.C. Agarwal A-56, Gulmohar Park New Delhi-110 049 Delhi 26851313 AGARWAL,DARSHANA 5 1337 (MRS.) (Faizi) W/o Shri O.P. Faizi Flat No. 258, Kailash Hills New Delhi-110 065 Delhi 51621300 6 0317 AGARWAL,MAM CHANDRA S/o Shri Ram Sharan Das Flat No.1133, Sector-29, Noida-201 301 Uttar Pradesh 0120-2453952 7 1427 AGARWAL,MOHAN BABU S/o Dr. C.B. Agarwal H.No. 78, Sukhdev Vihar New Delhi-110 025 Delhi 26919586 8 1021 AGARWAL,NEETA (MRS.) W/o Shri K.C. Agarwal B-608, Anand Lok Society Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 9312059240 9810139122 9 0687 AGARWAL,RAJEEV S/o Shri R.C. Agarwal 244, Bharat Apartment Sector-13, Rohini Delhi-110 085 Delhi 27554674 9810028877 11 1400 AGARWAL,S.K. S/o Shri Kishan Lal 78, Kirpal Apartments 44, I.P. Extension, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22721132 12 0933 AGARWAL,SUNIL KUMAR S/o Murlidhar Agarwal WB-106, Shakarpur, Delhi 9868036752 13 1199 AGARWAL,SURESH KUMAR S/o Shri Narain Dass B-28, Sector-53 Noida, (UP) Uttar Pradesh0120-2583477 9818791243 15 0242 AGGARWAL,ARUN S/o Shri Uma Shankar Agarwal Flat No.26, Trilok Apartments Plot No.85, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22433988 16 0194 AGGARWAL,MRIDUL (MRS.) W/o Shri Rajesh Aggarwal Flat No.214, Supreme Enclave Mayur Vihar Phase-I, Delhi-110 091 Delhi 22795565 17 0484 AGGARWAL,PRADEEP S/o Late R.P. -

TMS-LAJPATNAGAR Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

TMS-LAJPATNAGAR bus time schedule & line map TMS-LAJPATNAGAR Lajpat Nagar 2 Ring Road View In Website Mode The TMS-LAJPATNAGAR bus line Lajpat Nagar 2 Ring Road has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Lajpat Nagar 2 Ring Road: 6:00 AM - 9:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest TMS-LAJPATNAGAR bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next TMS- LAJPATNAGAR bus arriving. Direction: Lajpat Nagar 2 Ring Road TMS-LAJPATNAGAR bus Time Schedule 71 stops Lajpat Nagar 2 Ring Road Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:00 AM - 9:40 PM Monday 6:00 AM - 9:40 PM Lajpat Nagar 1 Ring Road Tuesday 6:00 AM - 9:40 PM PG DAV College / Sri Niwaspuri Wednesday 6:00 AM - 9:40 PM Nehru Nagar Thursday 6:00 AM - 9:40 PM Maharani Bagh / Ashram Friday 6:00 AM - 9:40 PM Bala Sahib Gurudwara Saturday 6:00 AM - 9:40 PM Sarai Kale Khan ISBT Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi Sarai Kale Khan ISBT TMS-LAJPATNAGAR bus Info Direction: Lajpat Nagar 2 Ring Road Indraprastha Park Stops: 71 Trip Duration: 116 min NH24, New Delhi Line Summary: Lajpat Nagar 1 Ring Road, PG DAV Nizamuddin Road Bridge College / Sri Niwaspuri, Nehru Nagar, Maharani Bagh / Ashram, Bala Sahib Gurudwara, Sarai Kale Khan Railway Road Bridge ISBT, Sarai Kale Khan ISBT, Indraprastha Park, Nizamuddin Road Bridge, Railway Road Bridge, Pragati Power Station, Indraprastha Depot, IP Power Pragati Power Station Station / ITO Ring Road, Ig Stadium, Gandhi Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi Darshan, Raj Ghat, Shanti Vana, Vijay Ghat, Hanuman Mandir / Yamuna Bazar, ISBT Ring -

41 S-II+Jangpura.Pdf

Election Commission of India Electoral Rolls for NCT of Delhi Back AC NAME LOCALITY LOCALITY DETAILS 41-JANGPURA 1-SARAI KALE KHAN 1 TO 447/2 2- A-BLOCK SARAI KALE KHAN 7 TO T86D 3-B - BLOCK SARAI KALE KHAN 34 TO T-86 4-T - BLOCK SARAI KALE KHAN 1 TO T-145 5-E - BLOCK ( BHOOT BANGLA ) SARAI KALE KHAN 76 TO 116 <> 1-HAZRAT NIZAMUDDIN NIZAMUDDIN (WEST) 3 TO T-B-36 2-DILDAR NAGAR BASTI HAZRAT NIZAMUDDIN 10/11 TO US 5/127 <> 1-NIZAM NAGAR HAZRAT NIZAMUDDIN NIZAMUDDIN (WEST) 1 TO VSA/5/86 2-KATRA NIZAMUDDIN (WEST) 23-T TO K- 556/104A 3-BASTI HZT NIZAMUDDIN 2 TO T-283 4- MUSHANWALI GALI, IMAMBRA NIZAMUDDIN WEST 18 TO A/47 5- IMAMBARA NIZAMUDDIN WEST 7-T TO 385-T <> 1-DILDAR ROAD NIZAMUDDIN WEST 2 TO T-561 2- KHUSRO NAGAR HAZRAT NIZAMUDDIN NIZAMUDDIN (WEST) 1 TO T-565 4- NALA PUSHTA, AMIR KHUSHRO NAGAR BASTI 3 TO T-423 <> 1-ITI ARAB KI SARAI, NIZAMUDEEN EAST, OPP POLICE STATION MATHURA ROAD 1 TO SHOP NO 1 <> 1-BUNGLOW NO 1- 35 NIZAMUDDIN EAST 1 TO 35 2-D- BLOCK 1-36 NIZAMUDDIN (EAST) 1 TO D-23 3- DAV SCHOOL POST OFFICE BLD NIZAMUDDIN EAST D A V TO PO BLDG 4-YMCA STAFF QTR NIZAMUDIN EAST 1 TO 4 <> 1-B-BLOCK MARKET NIZAMUDIN EAST 1 TO B-40 SF 2-B- BLOCK NIZAMUDIN EAST 1 TO B-28 3-C- BLOCK NIZAMUDDIN EAST 1 TO SNO-20 4- JAIPUR ESTATE NIZAMUDIN EAST 1 TO C-54 <> 1-MATHURA ROAD, JANGPURA B, BEHIND PRATAP MARKET NIZAMUDDIN EAST 5 TO R-24 2- MATHURA ROAD, JANGPURA B, B- BLOCK NIZAMUDDIN EAST 2 TO D-15 3- MATHURA ROAD, JANGPURA B, C- BLOCK NIZAMUDDIN EAST 7 TO C-63 4- MATHRA ROAD, JUNGPURA B, D- BLOCK NIZAMUDDIN EA ST 1 TO D-28 5- JUNGPURA B, PRATAP -

Ground Water Information Booklet of East District, Nct, Delhi

GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF EAST DISTRICT, NCT, DELHI CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES STATE UNIT OFFICE NEW DELHI DISTRICT BROCHURE OF EAST DISTRICT, NCT DELHI CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. DISTRICT AT A GLANCE ….…..i 1.0 INTRODUCTION ….…..1 2.0 RAINFALL & CLIMATE ….…..2 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY & SOIL TYPES ….…..2 4.0 GROUND WATER SCENARIO ….…..3 5.0 GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ………5 6.0 GROUND WATER RELATED ISSUES AND PROBLEMS ………5 7.0 AREA NOTIFIED …..…..6 8.0 RECOMMENDATIONS …..…..6 PLATES: 1. Hydrogeological Map …….7 2. Sub-surface geological cross section along Geeta Colony – Nagli Rajapur and …….9 Nagli Rajapur - Gazipur 3. Depth to water Level Map (May, 2012) …….10 4. Depth to Water Level Map (November, 2012) …….11 5. Electrical Conductivity Map …….12 6. Nitrate Distribution Map …….13 DISTRICT AT A GLANCE S.No. ITEMS STATISTICS 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical Area (Sq. Km.) 64 ii. Administrative Divisions (as on 31.03.2011) a) Number of Tehsils 3 b) Number of Villages 8 c) Number of Towns 3 iii. Population (as on 2011 Census) 17,07,725 a) Total Population 26,683 b) Population Density (persons/sq. km) 3,54,385 c) No. of Households iv. Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 451 (Shahdara) 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major Physiographic Units Yamuna Flood Plain, which is subdivided into Active Flood Plain and Older Flood Plain Major Drainage Yamuna River 3. LAND USE (Sq. Km.) a) Forest area 2.99 b) Water bodies 0.35 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES Silty-clay to clayey silt along with sandy loam 5.