Dissertation.Pdf (559.4Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hangar Digest Is a Publication of Th E Amc Museum Foundation, Inc

THE HANGAR DIGEST IS A PUBLICATION OF TH E AMC MUSEUM FOUNDATION, INC. V OLUME 10, I SSUE 3 Hangar Digest J ULY 2010 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: INSIDE THIS ISSUE Inside From the Story Director 32 Inside Cruisin‘ Story with Jim 32 Inside Meet the Story Volunteer 42 Inside Glider StoryLegacy 53 Inside Artifact Story Fact 84 Inside Foundation Story Notes 95 Inside Museum Story Scenes 116 LOOKING BACK Pictured above are some of the AMC Museum’s 138 volunteers. Recently the volun- teers were recognized at our 9th Annual Volunteer Luncheon. For the year 2009, Fifty years ago this 25,492 volunteer hours were logged in research, administration, tours, aircraft resto- month, the United ration, store sales and exhibit construction equating to an economic impact of ap- Nations intervened in proximately $721,330. Photo: Ev Sahrbeck the civil war in the Congo by airlifting During World War II, the United States produced the most formida- troops, supplies, ma- ble glider force in the world. The pilots who flew these gliders were terials and evacuating as unique as their motorless flying machines. Never before in his- refugees following tory had any nation produced aviators whose duty it was to delib- that nation’s inde- erately crash land and then go on to fight as combat infantrymen. pendence. Airlift sup- In this issue, we look at the development of the glider in “Glider port for the effort, Legacy in the United States Air Force”. dubbed Operation Raffle tickets are now on sale for your chance to win an original oil New Tape, included painting of the World War II B-17 “Outhouse Mouse” by renown 2,128 missions that aviation artist, Dave Godek. -

Up from Kitty Hawk Chronology

airforcemag.com Up From Kitty Hawk Chronology AIR FORCE Magazine's Aerospace Chronology Up From Kitty Hawk PART ONE PART TWO 1903-1979 1980-present 1 airforcemag.com Up From Kitty Hawk Chronology Up From Kitty Hawk 1903-1919 Wright brothers at Kill Devil Hill, N.C., 1903. Articles noted throughout the chronology provide additional historical information. They are hyperlinked to Air Force Magazine's online archive. 1903 March 23, 1903. First Wright brothers’ airplane patent, based on their 1902 glider, is filed in America. Aug. 8, 1903. The Langley gasoline engine model airplane is successfully launched from a catapult on a houseboat. Dec. 8, 1903. Second and last trial of the Langley airplane, piloted by Charles M. Manly, is wrecked in launching from a houseboat on the Potomac River in Washington, D.C. Dec. 17, 1903. At Kill Devil Hill near Kitty Hawk, N.C., Orville Wright flies for about 12 seconds over a distance of 120 feet, achieving the world’s first manned, powered, sustained, and controlled flight in a heavier-than-air machine. The Wright brothers made four flights that day. On the last, Wilbur Wright flew for 59 seconds over a distance of 852 feet. (Three days earlier, Wilbur Wright had attempted the first powered flight, managing to cover 105 feet in 3.5 seconds, but he could not sustain or control the flight and crashed.) Dawn at Kill Devil Jewel of the Air 1905 Jan. 18, 1905. The Wright brothers open negotiations with the US government to build an airplane for the Army, but nothing comes of this first meeting. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 154 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, AUGUST 1, 2008 No. 130 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. environmental group based in the Mad families that their interests are impor- The Chaplain, the Reverend Daniel P. River Valley of Vermont. Formed in tant enough for this Congress to stay Coughlin, offered the following prayer: the fall of 2007 by three local environ- here and lower gas prices. Is God in the motion or in the static? mentalists, Carbon Shredders dedicates In conclusion, God bless our troops, Is God in the problem or in the re- its time to curbing local energy con- and we will never forget September the solve? sumption, helping Vermonters lower 11th. Godspeed for the future careers to Is God in the activity or in the rest? their energy costs, and working to- Second District staff members, Chirag Is God in the noise or in the silence? wards a clean energy future. The group Shah and Kori Lorick. Wherever You are, Lord God, be in challenges participants to alter their f our midst, both now and forever. lifestyles in ways consistent with the Amen. goal of reducing energy consumption. COMMEMORATING THE MIN- In March, three Vermont towns f NEAPOLIS I–35W BRIDGE COL- passed resolutions introduced by Car- LAPSE THE JOURNAL bon Shredders that call on residents (Mr. ELLISON asked and was given The SPEAKER. The Chair has exam- and businesses to reduce their carbon footprint by 10 percent by 2010. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

The Day Was Coordinated by US Air Force Capt. Janelle

On the cover: U.S. Air Force Lt. Col Neal Snetsky, F-16 Fighter pilot with the 119th Fighter Squadron, stows his aircrew flight equipment after landing with 3,000 hrs. in the Fighting Falcon on Oct. 13, 2015. (U.S. Air National Guard photo illustration by Master Sgt. Andrew J. Moseley) OCTOBER 2015, VOL. 49 NO. 10 THE CONTRAIL STAFF 177TH FW COMMANDER COL . JOHN R. DiDONNA CHIEF, PUBLIC AFFAIRS CAPT. AMANDA BATIZ PUBLIC AFFAIRS SUPERINTENDENT MASTER SGT. ANDREW J. MOSELEY PHOTOJOURNALIST TECH. SGT. ANDREW J. MERLOCK PHOTOJOURNALIST SENIOR AIRMAN SHANE S. KARP EDITOR/PHOTOJOURNALIST SENIOR AIRMAN AMBER POWELL AVIATION HISTORIAN DR. RICHARD PORCELLI WWW.177FW.ANG.AF.MIL This funded newspaper is an authorized monthly publication for members of the U.S. Military Services. Contents of The Contrail are not necessarily the official view of, or endorsed by, the 177th Fighter Wing, the U.S. Government, the Department of Defense or the Depart- On desktop computers, click For back issues of The Contrail, ment of the Air Force. The editorial content is edited, prepared, and provided by the Public Affairs Office of the 177th Fighter Wing. All Ctrl+L for full screen. On mobile, and other multimedia products photographs are Air Force photographs unless otherwise indicated. tablet, or touch screen device, from the 177th Fighter Wing, tap or swipe to flip the page. please visit us at DVIDS! Total Force Integration and the Future by Col. Bradford Everman, 177th Operations Group Commander If you ask Airmen To position the wing for future missions, we must work aging aircraft with modern F-35 jets. -

Congressional Record—Senate S8652

S8652 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE June 28, 2007 body just gives out and drops. Do not back at their pursuers. At least one Catherine’s father, Bill Bittner, Sr., expect that to be anytime soon. round hit Ken’s cockpit, embedding was a close friend of Ken’s and his fish- I believe all ages and all occupations shrapnel in his arm and leg. ing partner. Bill and I often spent long should be part of a truly representative Determined to stay in the air as long summer days fishing with Ken and body. I also believe society works best as possible, Ken and George attacked a talking about World War II. when the energy and idealism of youth, group of bombers until they ran out of To this day, Ken’s family has strong youth, youth, pairs with the experience ammunition. The pair then landed at ties to Alaska. Ken’s son, Ken Jr., fol- and wisdom of age. Wheeler Field to resupply and refuel. lowed in his father’s footsteps and also America is the land of opportunities. While an air crew rearmed their became commander of the Alaska Air I don’t think our some 36 million citi- planes, the duo received a dressing National Guard. They remain the only zens over the age of 65 are disqualified down from a superior officer for taking father and son in our Nation’s history from participating in the life of the off without orders. The officer also in- to have achieved such an honor. Also, country that we—we—helped to build. -

And We Will Do It Again! Executive Director’S Report

NOTICE TO AIRMEN NOTAMPEARL HARBOR AVIATION MUSEUM • FORD ISLAND, HI SPRING 2020 | ISSUE #40 WE DID IT BEFORE ND WE CAN DO AE DID IT BEFORE IT A AND WE CAN DO IT AGAIN W GAIN AND WE WILL DO IT AGAIN! EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S REPORT Hard to believe how quickly our lives have changed. In the time it took for us to move from our initial draft to our final copy of this NOTAM--quarantine, lockdown, pandemic became the language and concerns of our day. Never has it been clearer that we are all connected and dependent upon one another to work together to solve problems. There are many lessons from our past that remind us we are indeed resilient. As President Franklin Delano Roosevelt once said,"So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is...fear itself — nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance. In every dark hour of our national life a leadership of frankness and of vigor has met with that understanding and support of the people themselves which is essential to victory. And I am convinced that you will again give that support to leadership in these critical days." The attack on Pearl Harbor galvanized our country into action. Our Greatest Generation were resilient, cementing the cornerstone of the American character. Many times since WWII that determination has rallied our nation to overcome the challenges we have faced together. So, too, will we this time. We hope you, your families, and your communities are safe, and that soon we can turn our energies to recovery. -

Congressional Record—Senate S8652

S8652 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE June 28, 2007 body just gives out and drops. Do not back at their pursuers. At least one Catherine’s father, Bill Bittner, Sr., expect that to be anytime soon. round hit Ken’s cockpit, embedding was a close friend of Ken’s and his fish- I believe all ages and all occupations shrapnel in his arm and leg. ing partner. Bill and I often spent long should be part of a truly representative Determined to stay in the air as long summer days fishing with Ken and body. I also believe society works best as possible, Ken and George attacked a talking about World War II. when the energy and idealism of youth, group of bombers until they ran out of To this day, Ken’s family has strong youth, youth, pairs with the experience ammunition. The pair then landed at ties to Alaska. Ken’s son, Ken Jr., fol- and wisdom of age. Wheeler Field to resupply and refuel. lowed in his father’s footsteps and also America is the land of opportunities. While an air crew rearmed their became commander of the Alaska Air I don’t think our some 36 million citi- planes, the duo received a dressing National Guard. They remain the only zens over the age of 65 are disqualified down from a superior officer for taking father and son in our Nation’s history from participating in the life of the off without orders. The officer also in- to have achieved such an honor. Also, country that we—we—helped to build. -

The Tangmere Logbook Magazineof

The Tangmere Logbook Magazine of the Tangmere Military Aviation Museum Autumn 2015 Jet-to-Jet Air Combat in Korea Robin Olds at Tangmere • Escape across Germany Tangmere Military Aviation Museum Trust Company Limited Patron: The Duke of Richmond and Gordon Hon. President: Air Marshal Sir Dusty Miller, KBE Hon. Life Vice-President: Alan Bower Hon. Life Vice-President: Duncan Simpson, OBE Council of Trustees Chairman: Group Captain David Baron, OBE David Burleigh, MBE Reginald Byron David Coxon Dudley Hooley Peter Lee Ken Shepherd Bill Walker Joyce Warren Officers of the Company Hon. Treasurer: Ken Shepherd Hon. Secretary: Joyce Warren Management Team Director: Dudley Hooley Curator: David Coxon General Manager: Peter Lee Engineering Manager: Reg Lambird Events Manager: David Burleigh, MBE Publicity Manager: Cherry Greveson Staffing Manager: Len Outridge Treasurer: Ken Shepherd Shop Manager: Sheila Shepherd Registered in England and Wales as a Charity Charity Commission Registration Number 299327 Registered Office: Tangmere, near Chichester, West Sussex PO20 2ES, England Telephone: 01243 790090 Fax: 01243 789490 Website: www.tangmere-museum.org.uk E-mail: [email protected] 2 The Tangmere Logbook The Tangmere Logbook Magazine of the Tangmere Military Aviation Museum Autumn 2015 Getting Used to It 4 And trying to keep up with the other chaps Robin Olds Making Tracks 12 Part Three of an account of my escape from captivity James Atterby McCairns MiG Alley 23 Jet fighters meet in combat for the first time Matt Wright Letters, Notes, and Queries 28 Korea: the RAF’s presence; answer to our last Photo Quiz; and a new brain teaser Published by the Society of Friends of the Tangmere Military Aviation Museum, Tangmere, near Chichester, West Sussex PO20 2ES, England Edited by Dr Reginald Byron, who may be contacted care of the Museum at the postal address given above, or by e-mail at [email protected] Copyright © 2015 by the Tangmere Military Aviation Museum Trust Company All rights reserved. -

July, August & September 2017

The Official Newsletter of the Valiant Air Command, Inc. 6600 Tico Road, Titusville, FL 32780 - (321) 268-1941 website: http://www.valiantaircommand.com email: [email protected] 3rd Quarter Review - July, August & September 2017 IRMA RECAP Damage to the museum was minimal. A few of the roof panels on the southeast corner of the main hangar were peeled back and some insulation was lost. While water intrusion is evident in several places within the museum, no major damage occurred to exhibits or aircraft. Our main hangar roof antenna was crushed, as a result, we had no internet or phone service. Some minor damage occurred to the TICO Warbird sign at SR405. Tico Road was blocked from SR405 to the museum due to several fallen trees blocking the road. There were massive amounts of debris in the parking lot and picnic area. A mighty team assembled the morning of September 12th to help clean up the mess. A grateful thanks to Joe Cross- Airshow Field Boss, Tom Etter-Director Facilities, Bob Filippi-Aircraft Restoration Expert, Charles Hammer-Chief Tico Belle Mechanic, Marvin Juhl-Director Maintenance, Pat and John Zelniak-Get-It-Done Custodians. A total of 25-man hours on Tuesday morning was spent picking up and hauling debris in members pick-up trucks to dump in undisclosed areas. Shortly after noon, everyone went home to take care of issues with their own properties. You should check out the “Fly-in Drive-in” Breakfast every Second Saturday, weather permitting. Chef Matt prepares your omlette to order. There is coffee, OJ, danish, fruit, sausage, bacon & more. -

The Spoken Word : Recollections of Dryden History : the Early Years / Curtis L

NASA SP-2003-4530 The Spoken Word: Recollections of Dryden History The Early Years edited by Curtis Peebles MONOGRAPHS IN AEROSPACE HISTORY #30 NASA SP-2003-4530 The Spoken Word: Recollections of Dryden History, The Early Years edited by Curtis Peebles NASA History Division Office of Policy and Plans NASA Headquarters Washington, DC 20546 Monographs in Aerospace History Number 30 2003 i Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The spoken word : recollections of Dryden history : the early years / Curtis L. Peebles, editor. p. cm. -- (Monographs in aerospace history ; no. 30) Includes bibliographical references and indes. 1. NASA Dryden Flight Research Center--History. 2. Aeronautics--Reserach--California--Rogers Lake (Kern County)--History. 3. Aeronautical engineers--United States--Interviews. 4. Airplanes--United States--Flight testing. 5. Oral history. I. Peebles, Curtis. II. Series. TL568.N23U62003 629.13’007’2079488–dc21 2002045204 ____________________________________________________________ For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-9328 ii Table of Contents Section I: Foundations ...............................................................................................................1 Walter C. Williams.....................................................................................................7 Clyde Bailey, Richard Cox, Don Borchers, and Ralph Sparks................................19 John Griffith.............................................................................................................47 -

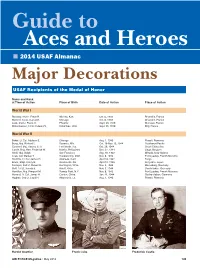

Guide to Aces and Heroes ■ 2014 USAF Almanac Major Decorations

Guide to Aces and Heroes ■ 2014 USAF Almanac Major Decorations USAF Recipients of the Medal of Honor Name and Rank at Time of Action Place of Birth Date of Action Place of Action World War I Bleckley, 2nd Lt. Erwin R. Wichita, Kan. Oct. 6, 1918 Binarville, France Goettler, 1st Lt. Harold E. Chicago Oct. 6, 1918 Binarville, France Luke, 2nd Lt. Frank Jr. Phoenix Sept. 29, 1918 Murvaux, France Rickenbacker, 1st Lt. Edward V. Columbus, Ohio Sept. 25, 1918 Billy, France World War II Baker, Lt. Col. Addison E. Chicago Aug. 1, 1943 Ploesti, Romania Bong, Maj. Richard I. Superior, Wis. Oct. 10-Nov. 15, 1944 Southwest Pacific Carswell, Maj. Horace S. Jr. Fort Worth, Tex. Oct. 26, 1944 South China Sea Castle, Brig. Gen. Frederick W. Manila, Philippines Dec. 24, 1944 Liège, Belgium Cheli, Maj. Ralph San Francisco Aug. 18, 1943 Wewak, New Guinea Craw, Col. Demas T. Traverse City, Mich. Nov. 8, 1942 Port Lyautey, French Morocco Doolittle, Lt. Col. James H. Alameda, Calif. April 18, 1942 Tokyo Erwin, SSgt. Henry E. Adamsville, Ala. April 12, 1945 Koriyama, Japan Femoyer, 2nd Lt. Robert E. Huntington, W.Va. Nov. 2, 1944 Merseburg, Germany Gott, 1st Lt. Donald J. Arnett, Okla. Nov. 9, 1944 Saarbrücken, Germany Hamilton, Maj. Pierpont M. Tuxedo Park, N.Y. Nov. 8, 1942 Port Lyautey, French Morocco Howard, Lt. Col. James H. Canton, China Jan. 11, 1944 Oschersleben, Germany Hughes, 2nd Lt. Lloyd H. Alexandria, La. Aug. 1, 1943 Ploesti, Romania Harold Goettler Frank Luke Frederick Castle AIR FORCE Magazine / May 2014 105 Neel Kearby Louis Sebille George Day *Living Medal of Honor recipient World War II (continued) Jerstad, Maj.