Submission to the Senate Community Affairs Committee: Number of Women in Australia Who Have Had Transvaginal Mesh Implants and Related Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learner Notification International Society for Heart & Lung

Learner Notification International Society for Heart & Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) 41st Annual Meeting & Scientific Sessions Virtual Experience April 24 – 28, 2021 Live Virtual Acknowledgement of Financial Commercial Support Abbott Medtronic United Therapeutics Acknowledgement of In-Kind Commercial Support No in-kind commercial support was received for this educational activity. Satisfactory Completion Learners must complete an evaluation form to receive a certificate of completion. Your chosen sessions must be attended in their entirety as partial credit of individual sessions is not available. If you are seeking continuing education credit for a specialty not listed below, it is your responsibility to contact your licensing/certification board to determine course eligibility for your licensing/certification requirement. Physicians (ACCME) The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians. Credit Designation Statement - ISHLT designates this live virtual activity for a maximum of 32.00 AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. Accreditation Statement In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Amedco LLC and ISHLT. Amedco LLC is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team. Nurses (ANCC) - Credit Designation Statement - Amedco LLC designates this live virtual activity for a maximum of 32.00 ANCC contact hours. Pharmacists (ACPE) - Credit Designation Statement - Amedco LLC designates this live virtual activity for a maximum of 32.00 knowledge-based CPE contact hours. -

2015 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 MARCH 2016 TO OUR SHAREHOLDERS ALEX GORSKY Chairman, Board of Directors and Chief Executive Officer This year at Johnson & Johnson, we are proud this aligned with our values. Our Board of WRITTEN OVER to celebrate 130 years of helping people Directors engages in a formal review of 70 YEARS AGO, everywhere live longer, healthier and happier our strategic plans, and provides regular OUR CREDO lives. As I reflect on our heritage and consider guidance to ensure our strategy will continue UNITES & our future, I am optimistic and confident in the creating better outcomes for the patients INSPIRES THE long-term potential for our business. and customers we serve, while also creating EMPLOYEES long-term value for our shareholders. OF JOHNSON We manage our business using a strategic & JOHNSON. framework that begins with Our Credo. Written OUR STRATEGIES ARE BASED ON over 70 years ago, it unites and inspires the OUR BROAD AND DEEP KNOWLEDGE employees of Johnson & Johnson. It reminds OF THE HEALTH CARE LANDSCAPE us that our first responsibility is to the patients, IN WHICH WE OPERATE. customers and health care professionals who For 130 years, our company has been use our products, and it compels us to deliver driving breakthrough innovation in health on our responsibilities to our employees, care – from revolutionizing wound care in communities and shareholders. the 1880s to developing cures, vaccines and treatments for some of today’s most Our strategic framework positions us well pressing diseases in the world. We are acutely to continue our leadership in the markets in aware of the need to evaluate our business which we compete through a set of strategic against the changing health care environment principles: we are broadly based in human and to challenge ourselves based on the health care, our focus is on managing for the results we deliver. -

Personalized Medicine for Reconstruction of Critical-Size Bone

www.nature.com/npjregenmed ARTICLE OPEN Personalized medicine for reconstruction of critical-size bone defects – a translational approach with customizable vascularized bone tissue ✉ Annika Kengelbach-Weigand 1 , Carolina Thielen 1, Tobias Bäuerle2, Rebekka Götzl 1,5, Thomas Gerber3, Carolin Körner4, Justus P. Beier1,5, Raymund E. Horch 1 and Anja M. Boos1,5 Tissue engineering principles allow the generation of functional tissues for biomedical applications. Reconstruction of large-scale bone defects with tissue-engineered bone has still not entered the clinical routine. In the present study, a bone substitute in combination with mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) and endothelial progenitor cells (EPC) with or without growth factors BMP-2 and VEGF-A was prevascularized by an arteriovenous (AV) loop and transplanted into a critical-size tibia defect in the sheep model. With 3D imaging and immunohistochemistry, we could show that this approach is a feasible and simple alternative to the current clinical therapeutic option. This study serves as proof of concept for using large-scale transplantable, vascularized, and customizable bone, generated in a living organism for the reconstruction of load-bearing bone defects, individually tailored to the patient’s needs. With this approach in personalized medicine for the reconstruction of critical-size bone defects, regeneration of parts of the human body will become possible in the near future. npj Regenerative Medicine (2021) 6:49 ; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41536-021-00158-8 1234567890():,; INTRODUCTION vascular networks consisting of endothelial cells can be created Therapeutic options for bone defects that cannot heal sponta- directly within tissue replacement materials7. Vascularization may neously, the so-called critical-size bone defects, are still limited be further supported by the addition of endothelial cells and and often associated with a great social burden. -

HEALTH PROFESSIONAL CONSULTANT to a PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANY V JOHNSON & JOHNSON Nicorette Advertisement

CASE AUTH/2930/1/17 HEALTH PROFESSIONAL CONSULTANT TO A PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANY v JOHNSON & JOHNSON Nicorette advertisement A complaint was received in a private capacity that the implication was that the statement in from a health professional who stated that he/ question related to a feature of Nicorette, that the she worked as a consultant to a pharmaceutical product itself had incredible features and/or that company. health professionals would be doing something incredible by prescribing it. The implication was The complaint concerned an online advertisement misleading and exaggerated and breaches of the for Nicorette (nicotine) issued by Johnson & Code ruled. Johnson published in Pulse. The complainant stated at the time of submitting The complainant provided a screenshot of a the complaint that he/she was a health professional banner advertisement. It included ‘Nicorette. Do who worked as a consultant to Novartis. It had something incredible’. The complainant did not previously been decided, following consideration believe that the word ‘incredible’ was suitable. This by the then Code of Practice Committee and the information did not appear to be balanced and was ABPI Board of Management, that private complaints exaggerated. The claim was taken directly from from pharmaceutical company employees had material aimed at the general public and it appeared to be accepted. To avoid this becoming a means that Johnson & Johnson had not undertaken a of circumventing the normal procedures for sufficiently robust review when translating to intercompany complaints, the employing company promotion aimed at health professionals. would be named in the report. The complainant would be advised that this would happen and be The detailed response from Johnson & Johnson is given an opportunity to withdraw the complaint. -

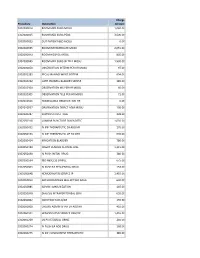

Procedure Description Charge Amount 0302000014 ROOM MED

Charge Procedure Description Amount 0302000014 ROOM MED SURG MOSU 1,040.00 0302000015 ROOM MED SURG PEDS 3,500.00 0302000033 OUT PATIENT BED MOSU 0.00 0302000035 ROOM INTERMEDIATE MOSU 2,055.00 0302000043 ROOM HOSPICE MOSU 805.00 0302000045 ROOM MED SURG W TELE MOSU 1,530.00 0302000050 OBSERVATION INTERM PER HR MOSU 97.00 0302002283 FECAL MANAGEMENT SYSTEM 694.00 0302010232 CATH INDWELL BLADDER SIMPLE 185.00 0302010304 OBSERVATION MS PER HR MOSU 60.00 0302010305 OBSERVATION TELE PER HR MOSU 71.00 0302010556 NONBILLABLE OBSERVATION HR 0.00 0302010557 OBSERVATION DIRECT ADM MOSU 130.00 0302020287 SUPPLIES CHEST TUBE 228.00 0302050318 LUMBAR PUNCTURE DIAGNOSTIC 1,035.00 0302050451 IV INF THERAPEUTIC EA ADD HR 170.00 0302050453 IV INF THERAPEUTIC UP TO 1HR 635.00 0302050454 IRRIGATION BLADDER 780.00 0302050480 INSERT VENOUS CENTRAL LINE 1,315.00 0302050490 IV PUSH INITIAL DRUG 380.00 0302050534 I&D ABSCESS SIMPLE 675.00 0302050603 IV PUSH EA SEQUENTIAL DRUG 153.00 0302050648 HEMODIALYSIS SERVICE IP 1,455.00 0302050813 ARTHROCENTESIS MAJ JNT WO IMAG 630.00 0302050885 ADMIN IMMUNIZATION 145.00 0302050948 DIALYSIS INTRAPERITONEAL SERV 655.00 0302060002 INJECTION SUB-Q/IM 155.00 0302060008 CHEMO ADMIN IV INF EA ADD HR 410.00 0302060101 HEMODIALYSIS SERVICE OBS/OP 1,455.00 0302060269 US PV RESIDUAL URINE 240.00 0302060274 IV PUSH EA ADD DRUG 168.00 0302060275 IV INF CONCURRENT THERAPEUTIC 385.00 0302060276 IV INF SEQUENTIAL THER UP TO 1 191.00 0302060293 INSERT STRAIGHT CATH THERAPEUT 185.00 0302060372 CHEMO ADMIN IV INF SEQ 1 HR 525.00 0302060373 -

Nicorette Invisipatch 25 Mg/16 H Transdermal Patch

SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Nicorette invisipatch 25 mg/16 h transdermal patch Nicorette invisipatch 15 mg/16 h transdermal patch Nicorette invisipatch 10 mg/16 h transdermal patch 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each transdermal patch contains nicotine 1.75 mg/cm2. Nicorette invisipatch 25 mg/16 h, of 22.5 cm2 size contains nicotine 39.37 mg and releases nicotine 25 mg /16 hours Nicorette invisipatch 15 mg/16 h, of 13.5 cm2 size contains nicotine 23.62 mg and releases nicotine 15 mg /16 hours Nicorette invisipatch 10 mg/16 h, of 9.0 cm2 size contains nicotine 15.75 mg and releases nicotine 10 mg /16 hours For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Transdermal patch Beige, semi-transparent, rectangular patch with rounded edges and light-brown “Nicorette” printing, is placed on an easily removable layer coated with aluminium and silicon and is formed by nicotine layer and adhesive acrylate layer. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1. Therapeutic indication Nicorette invisipatch is to be used for the treatment of tobacco dependence in adults by relief of nicotine withdrawal symptoms, including cravings, during a quit attempt. Permanent cessation of tobacco use is the eventual objective. Nicorette invisipatch is indicated in adults. Nicorette invisipatch should preferably be used in conjunction with a behavioral support program. 4.2. Posology and method of administration Posology Subjects should stop smoking completely during the course of treatment with Nicorette invisipatch. Administration of nicotine should be stopped immediately if any symptoms of overdose listed in Section 4.9 occur. -

Over-The-Counter Mail Order Program 1-866-768-8490 As a Superior

Over-the-Counter Mail Order Program 1-866-768-8490 As a Superior value-added service, STAR+PLUS and STAR Health members can get $30 in items every 3 months (90 days). STAR members can get $25 in items every 3 months (90 days). No prescription is needed. To order, please call 1-866-768-8490. Have your Superior ID card ready when you call. Your order will be mailed to your home in 5-10 days. Please use these items only as directed. If you have questions about safe use of any of these items, talk to your doctor. Item Description Compare to: Price Item Description Compare to: Price Analgesics Eye Care 1 Ibuprofen 200mg tab Motrin IB $6 31 Tetrahydrozoline drops Visine $4 2 Naproxen sod 220mg tab Aleve $9 61 Lubricating eye drops Refresh Tears $7 3 Aspirin 325mg tab Bayer Aspirin $5 First Aid Creams/Ointments 4 Aspirin ec 325 mg tab Ecotrin $6 32 Calamine lotion Calamine Lotion $4 5 Aspirin ec 81 mg Halfprin $5 33 Hydrocortisone !5 cream Cort-Aid $4 6 Acetaminophen 500mg tab Tylenol Extra Str $6 34 Triple antibiotic ointment Neosporin $5 7 Mentholated ointment Ben Gay $6 60 Medicated lip balm Carmex $3 Antacids First Aid Supplies 8 Simethicone 80mg tab Mylanta Anti-Gas $6 35 Athletic bandage Ace Bandage $7 9 Calc carb 500mg chewable TUMS $6 36 Adhesive tape First-Aid Tape $3 10 Famotidine 10mg tab Pepcid AC $9 37 Band-aids Band-Aids $4 Antidiarrheals 38 Carbamide peroxide Debrox Drops $4 11 Loperamide 2mg cap Imodium $5 39 Gauze pads Gauze Pads $3 12 Bismuth mixture Pepto-Bismol $5 40 Cotton swab Q-Tips $4 Antifungals 41 Oral thermometer Thermometer -

![[J-52A-2014] in the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania Middle District](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1548/j-52a-2014-in-the-supreme-court-of-pennsylvania-middle-district-941548.webp)

[J-52A-2014] in the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania Middle District

[J-52A-2014] IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PENNSYLVANIA MIDDLE DISTRICT COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA : 84 MAP 2011 : : Appeal from the decision of the : Commonwealth Court (Opinion re Post- v. : Trial Motions of the Commonwealth and : Johnson & Johnson) dated 8/31/11 at No. : 212 MD 2004 TAP PHARMACEUTICAL PRODUCTS, : INC.; ABBOTT LABORATORIES; : ASTRAZENECA PLC; ASTRAZENECA, : HOLDINGS, INC.; ASTRAZENECA : PHARMACEUTICALS LP; : ASTRAZENECA LP; BAYER AG; BAYER : CORPORATION; SMITHKLINE : BEECHAM CORPORATION D/B/A : GLAXOSMITHKLINE; PFIZER, INC.; : PHARMACIA CORPORATION; : JOHNSON & JOHNSON; ALZA : CORPORATION; CENTROCOR, INC.; : ETHICON, INC.; JANSSEN : PHARMACEUTICAL PRODUCTS, L.P.; : MCNEIL-PPC, INC.; ORTHO BIOTECH, : INC.; ORTHO BIOTECH PRODUCTS; : L.P.; ORTHO-MCNEIL : PHARMACEUTICAL, INC.; AMGEN INC.; : IMMUNEX CORPORATION; BRISTOL- : MYERS SQUIBB COMPANY; BAXTER : INTERNATIONAL INC.; BAXTER : HEALTHCARE CORPORATION; : IMMUNO-U.S., INC.; AVENTIS : PHARMACEUTICALS, INC.; AVENTIS : BEHRING, L.L.C.; HOECHST MARION : ROUSSEL, INC., BOEHRINGER : INGELHEIM CORPORATION; : BOEHRINGER INGELHEIM : PHARMACEUTICALS, INC.; BEN VENUE : LABORATORIES; BEDFORD : LABORATORIES; ROXANE : LABORATORIES; SCHERING-PLOUGH : CORPORATION; WARRICK : PHARMACEUTICALS CORPORATION; : SCHERING SALES CORPORATION; : DEY, INC. : : DONNA A. BOSWELL, ESQ., ANN M. : VICKERY, ESQ., AND JOSEPH A. : YOUNG, ESQ., : Intervenors : : APPEAL OF: JOHNSON & JOHNSON, : ALZA CORPORATION, CENTOCOR, : INC., ETHICON, INC., JANSSEN : PHARMACEUTICAL PRODUCTS, L.P., : MCNEIL-PPC, INC., ORTHO BIOTECH, : INC., ORTHO BIOTECH PRODUCTS, : L.P., AND ORTHO-MCNEIL : PHARMACEUTICAL, INC. : (COLLECTIVELY, THE “JOHNSON & : JOHNSON DEFENDANTS”) : ORDER PER CURIAM DECIDED: June 16, 2014 AND NOW, this 16th day of June, 2014, the Order of the Commonwealth Court is VACATED, and the matter is remanded per the terms of Mr. Justice Baer’s responsive opinion in Commonwealth v. TAP Pharm. Prods., Inc., J-52B-2014, ___ A.3d ___ (Pa. -

FDA Listing of Authorized Generics As of July 1, 2021

FDA Listing of Authorized Generics as of July 1, 2021 Note: This list of authorized generic drugs (AGs) was created from a manual review of FDA’s database of annual reports submitted to the FDA since January 1, 1999 by sponsors of new drug applications (NDAs). Because the annual reports seldom indicate the date an AG initially entered the market, the column headed “Date Authorized Generic Entered Market” reflects the period covered by the annual report in which the AG was first reported. Subsequent marketing dates by the same firm or other firms are not included in this listing. As noted, in many cases FDA does not have information on whether the AG is still marketed and, if not still marketed, the date marketing ceased. Although attempts have been made to ensure that this list is as accurate as possible, given the volume of d ata reviewed and the possibility of database limitations or errors, users of this list are cautioned to independently verify the information on the list. We welcome comments on and suggested changes (e.g., additions and deletions) to the list, but the list may include only information that is included in an annual report. Please send suggested changes to the list, along with any supporting documentation to: [email protected] A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V X Y Z NDA Applicant Date Authorized Generic Proprietary Name Dosage Form Strength Name Entered the Market 1 ACANYA Gel 1.2% / 2.5% Bausch Health 07/2018 Americas, Inc. -

Lna 2006 Profiles J.Qxp

1 | Advertising Age | June 26, 2006 SpecialSpecial ReportReport:100 Profiles LEADING NATIONAL ADVERTISERSSupplement SUPPLEMENT June 26, 2006 100 LEADING NATIONAL ADVERTISERS Profiles of the top 100 U.S. marketers in this 51st annual ranking INSIDE TOP 100 RANKING COMPANY PROFILES SPONSORED BY The nation’s leading marketers Lead marketing personnel, ranked by U.S. advertising brands, agencies, agency expenditures for 2005. contacts, as well as advertising Includes data from TNS Media spending by media and brand, Intelligence and Ad Age’s sales, earnings and more for proprietary estimates of the country’s 100 largest unmeasured spending. PAGE 8 advertisers PAGE 10 This document, and information contained therein, is the copyrighted property of Crain Communications Inc. and The Ad Age Group (© Copyright 2006) and is for your personal, non-commercial use only. You may not reproduce, display on a website, distribute, sell or republish this document, or information contained therein, without prior written consent of The Ad Age Group. Are proud to connect you with the leading CMOs See all the interviews at adage.com/point LAUNCHING JUNE 28 © 2006 Crain Communications Inc. www.adage.com 3 | Advertising Age | June 26, 2006 Special Report 100 LEADING NATIONAL ADVERTISERS SUPPLEMENT ABOUT THIS PROFILE EDITION THE 51ST ANNUAL 100 Leading National the Top 100 ($40.13 billion) and for all measured spending in 18 national media, Advertisers Report crowned acquisition- advertisers ($122.79 billion) in the U.S. Yellow Pages Association contributed ladened Procter & Gamble Co. as the top U.S. ad spending by ad category: This spending in Yellow Pages and TNS Marx leader, passing previous kingpen General chart (Page 6) breaks out 18 measured Promotion Intelligence provided free- Motors Corp. -

Lifescan Ethicon

LouiseLouise MehrotraMehrotra ViceVice PresidentPresident InvestorInvestor RelationsRelations ““SafeSafe HarborHarbor”” StatementStatement This presentation may contain “forward-looking statements” as defined in the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. These statements are based on current expectations of future events. If underlying assumptions prove inaccurate or unknown risks or uncertainties materialize, actual results could vary materially from the Company’s expectations and projections. Risks and uncertainties include general industry conditions and competition; economic conditions, such as interest rate and currency exchange rate fluctuations; technological advances and patents attained by competitors; challenges inherent in new product development, including obtaining regulatory approvals; domestic and foreign health care reforms and governmental laws and regulations; and trends toward health care cost containment. A further list and description of these risks, uncertainties and other factors can be found in Exhibit 99 to the Company’s Annual Report on Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2006. Copies of this Form 10-K, as well as subsequent filings, are available online at www.sec.gov, www.jnj.com or on request from the Company. The Company does not undertake to update any forward-looking statements as a result of new information or future events or developments. WilliamWilliam C.C. WeldonWeldon ChairmanChairman ofof thethe BoardBoard && ChiefChief ExecutiveExecutive OfficerOfficer TodayToday’’ss AgendaAgenda -

Nicorette Invisipatch 25 Mg/16 H Transdermal Patch Nicorette Invisipatch 15 Mg/16 H Transdermal Patch Nicorette Invisipatch 10 Mg/16 H Transdermal Patch

Package leaflet: Information for the user Nicorette invisipatch 25 mg/16 h transdermal patch Nicorette invisipatch 15 mg/16 h transdermal patch Nicorette invisipatch 10 mg/16 h transdermal patch (nicotine) Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start using this medicine because it contains important information for you. Always use this medicine exactly as described in this leaflet or as your doctor or pharmacist have told you. - Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. - Ask your pharmacist if you need more information or advice. - If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. - You must talk to a doctor if you have not been able to stop smoking after 6 months of treatment with Nicorette Invisipatch. What is in this leaflet: 1. What Nicorette invisipatch is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before you use Nicorette invisipatch 3. How to use Nicorette invisipatch 4. Possible side effects 5 How to store Nicorette invisipatch 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What Nicorette invisipatch is and what it is used for Nicorette invisipatch is a medicinal product helping you to stop smoking. Nicorette invisipatch is used to treat tobacco dependence, to relieve cravings for smoking (nicotine) and nicotine withdrawal symptoms, which helps the motivated smokers to stop smoking. When you stop smoking and providing your body with nicotine from tobacco, you can experience unpleasant feelings called withdrawal symptoms. By using Nicorette invisipatch you can prevent or reduce these unpleasant feelings - by using Nicorette invisipatch patches you continue to provide your body with small amount of nicotine in its pure form, which does not bring about health risks associated with smoking.