EARLY PHASES of PROTOSTARS: Star Formation and Protoplanetary Disks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plasma Physics and Pulsars

Plasma Physics and Pulsars On the evolution of compact o bjects and plasma physics in weak and strong gravitational and electromagnetic fields by Anouk Ehreiser supervised by Axel Jessner, Maria Massi and Li Kejia as part of an internship at the Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy, Bonn March 2010 2 This composition was written as part of two internships at the Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy in April 2009 at the Radiotelescope in Effelsberg and in February/March 2010 at the Institute in Bonn. I am very grateful for the support, expertise and patience of Axel Jessner, Maria Massi and Li Kejia, who supervised my internship and introduced me to the basic concepts and the current research in the field. Contents I. Life-cycle of stars 1. Formation and inner structure 2. Gravitational collapse and supernova 3. Star remnants II. Properties of Compact Objects 1. White Dwarfs 2. Neutron Stars 3. Black Holes 4. Hypothetical Quark Stars 5. Relativistic Effects III. Plasma Physics 1. Essentials 2. Single Particle Motion in a magnetic field 3. Interaction of plasma flows with magnetic fields – the aurora as an example IV. Pulsars 1. The Discovery of Pulsars 2. Basic Features of Pulsar Signals 3. Theoretical models for the Pulsar Magnetosphere and Emission Mechanism 4. Towards a Dynamical Model of Pulsar Electrodynamics References 3 Plasma Physics and Pulsars I. The life-cycle of stars 1. Formation and inner structure Stars are formed in molecular clouds in the interstellar medium, which consist mostly of molecular hydrogen (primordial elements made a few minutes after the beginning of the universe) and dust. -

XIII Publications, Presentations

XIII Publications, Presentations 1. Refereed Publications E., Kawamura, A., Nguyen Luong, Q., Sanhueza, P., Kurono, Y.: 2015, The 2014 ALMA Long Baseline Campaign: First Results from Aasi, J., et al. including Fujimoto, M.-K., Hayama, K., Kawamura, High Angular Resolution Observations toward the HL Tau Region, S., Mori, T., Nishida, E., Nishizawa, A.: 2015, Characterization of ApJ, 808, L3. the LIGO detectors during their sixth science run, Classical Quantum ALMA Partnership, et al. including Asaki, Y., Hirota, A., Nakanishi, Gravity, 32, 115012. K., Espada, D., Kameno, S., Sawada, T., Takahashi, S., Ao, Y., Abbott, B. P., et al. including Flaminio, R., LIGO Scientific Hatsukade, B., Matsuda, Y., Iono, D., Kurono, Y.: 2015, The 2014 Collaboration, Virgo Collaboration: 2016, Astrophysical Implications ALMA Long Baseline Campaign: Observations of the Strongly of the Binary Black Hole Merger GW150914, ApJ, 818, L22. Lensed Submillimeter Galaxy HATLAS J090311.6+003906 at z = Abbott, B. P., et al. including Flaminio, R., LIGO Scientific 3.042, ApJ, 808, L4. Collaboration, Virgo Collaboration: 2016, Observation of ALMA Partnership, et al. including Asaki, Y., Hirota, A., Nakanishi, Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger, Phys. Rev. K., Espada, D., Kameno, S., Sawada, T., Takahashi, S., Kurono, Lett., 116, 061102. Y., Tatematsu, K.: 2015, The 2014 ALMA Long Baseline Campaign: Abbott, B. P., et al. including Flaminio, R., LIGO Scientific Observations of Asteroid 3 Juno at 60 Kilometer Resolution, ApJ, Collaboration, Virgo Collaboration: 2016, GW150914: Implications 808, L2. for the Stochastic Gravitational-Wave Background from Binary Black Alonso-Herrero, A., et al. including Imanishi, M.: 2016, A mid-infrared Holes, Phys. -

Exors and the Stellar Birthline Mackenzie S

A&A 600, A133 (2017) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201630196 & c ESO 2017 Astrophysics EXors and the stellar birthline Mackenzie S. L. Moody1 and Steven W. Stahler2 1 Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA e-mail: [email protected] 2 Astronomy Department, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA e-mail: [email protected] Received 6 December 2016 / Accepted 23 February 2017 ABSTRACT We assess the evolutionary status of EXors. These low-mass, pre-main-sequence stars repeatedly undergo sharp luminosity increases, each a year or so in duration. We place into the HR diagram all EXors that have documented quiescent luminosities and effective temperatures, and thus determine their masses and ages. Two alternate sets of pre-main-sequence tracks are used, and yield similar results. Roughly half of EXors are embedded objects, i.e., they appear observationally as Class I or flat-spectrum infrared sources. We find that these are relatively young and are located close to the stellar birthline in the HR diagram. Optically visible EXors, on the other hand, are situated well below the birthline. They have ages of several Myr, typical of classical T Tauri stars. Judging from the limited data at hand, we find no evidence that binarity companions trigger EXor eruptions; this issue merits further investigation. We draw several general conclusions. First, repetitive luminosity outbursts do not occur in all pre-main-sequence stars, and are not in themselves a sign of extreme youth. They persist, along with other signs of activity, in a relatively small subset of these objects. -

The Formation of Brown Dwarfs 459

Whitworth et al.: The Formation of Brown Dwarfs 459 The Formation of Brown Dwarfs: Theory Anthony Whitworth Cardiff University Matthew R. Bate University of Exeter Åke Nordlund University of Copenhagen Bo Reipurth University of Hawaii Hans Zinnecker Astrophysikalisches Institut, Potsdam We review five mechanisms for forming brown dwarfs: (1) turbulent fragmentation of molec- ular clouds, producing very-low-mass prestellar cores by shock compression; (2) collapse and fragmentation of more massive prestellar cores; (3) disk fragmentation; (4) premature ejection of protostellar embryos from their natal cores; and (5) photoerosion of pre-existing cores over- run by HII regions. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. Their relative importance probably depends on environment, and should be judged by their ability to reproduce the brown dwarf IMF, the distribution and kinematics of newly formed brown dwarfs, the binary statis- tics of brown dwarfs, the ability of brown dwarfs to retain disks, and hence their ability to sustain accretion and outflows. This will require more sophisticated numerical modeling than is presently possible, in particular more realistic initial conditions and more realistic treatments of radiation transport, angular momentum transport, and magnetic fields. We discuss the mini- mum mass for brown dwarfs, and how brown dwarfs should be distinguished from planets. 1. INTRODUCTION form a smooth continuum with those of low-mass H-burn- ing stars. Understanding how brown dwarfs form is there- The existence of brown dwarfs was first proposed on the- fore the key to understanding what determines the minimum oretical grounds by Kumar (1963) and Hayashi and Nakano mass for star formation. In section 3 we review the basic (1963). -

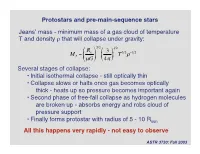

Protostars and Pre-Main-Sequence Stars Jeans' Mass

Protostars and pre-main-sequence stars Jeans’ mass - minimum mass of a gas cloud of temperature T and density r that will collapse under gravity: 3 2 1 2 Ê Rg ˆ Ê 3 ˆ 3 2 -1 2 MJ = Á ˜ Á ˜ T r Ë mG¯ Ë 4p ¯ Several stages of collapse: • Initial isothermal collapse - still optically thin • Collapse† slows or halts once gas becomes optically thick - heats up so pressure becomes important again • Second phase of free-fall collapse as hydrogen molecules are broken up - absorbs energy and robs cloud of pressure support • Finally forms protostar with radius of 5 - 10 Rsun All this happens very rapidly - not easy to observe ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Observationally, classify young stellar objects (YSOs) by looking at their spectral energy distributions (SEDs). Four main classes of object have been identified: flux Class 0 source wavelength in microns 1 10 100 (10-6 m) Observationally, this is a source whose SED peaks in the far-infrared or mm part of the spectrum. No flux in the near-infrared (at a few microns). Effective temperature is several 10s of degrees Kelvin. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 What are Class 0 sources? • Still very cool - not much hotter than molecular cloud cores. Implies extreme youth. • Deeply embedded in gas and dust, any shorter wavelength radiation is absorbed and reradiated at longer wavelengths before escaping. • Fairly small numbers - consistent with short duration of the initial collapse. • Outflows are seen - suggests a protostar is forming. Earliest observed stage of star formation… ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Class 1 flux Very large infrared excess Protostellar black body emission wavelength in microns 1 10 100 (10-6 m) Class 1 sources also have SEDs that rise into the mid and far infrared. -

Issue 36, June 2008

June2008 June2008 In This Issue: 7 Supernova Birth Seen in Real Time Alicia Soderberg & Edo Berger 23 Arp299 With LGS AO Damien Gratadour & Jean-René Roy 46 Aspen Instrument Update Joseph Jensen On the Cover: NGC 2770, home to Supernova 2008D (see story starting on page 7 Engaging Our Host of this issue, and image 52 above showing location Communities of supernova). Image Stephen J. O’Meara, Janice Harvey, was obtained with the Gemini Multi-Object & Maria Antonieta García Spectrograph (GMOS) on Gemini North. 2 Gemini Observatory www.gemini.edu GeminiFocus Director’s Message 4 Doug Simons 11 Intermediate-Mass Black Hole in Gemini South at moonset, April 2008 Omega Centauri Eva Noyola Collisions of 15 Planetary Embryos Earthquake Readiness Joseph Rhee 49 Workshop Michael Sheehan 19 Taking the Measure of a Black Hole 58 Polly Roth Andrea Prestwich Staff Profile Peter Michaud 28 To Coldly Go Where No Brown Dwarf 62 Rodrigo Carrasco Has Gone Before Staff Profile Étienne Artigau & Philippe Delorme David Tytell Recent 31 66 Photo Journal Science Highlights North & South Jean-René Roy & R. Scott Fisher Photographs by Gemini Staff: • Étienne Artigau NICI Update • Kirk Pu‘uohau-Pummill 37 Tom Hayward GNIRS Update 39 Joseph Jensen & Scot Kleinman FLAMINGOS-2 Update Managing Editor, Peter Michaud 42 Stephen Eikenberry Science Editor, R. Scott Fisher MCAO System Status Associate Editor, Carolyn Collins Petersen 44 Maxime Boccas & François Rigaut Designer, Kirk Pu‘uohau-Pummill 3 Gemini Observatory www.gemini.edu June2008 by Doug Simons Director, Gemini Observatory Director’s Message Figure 1. any organizations (Gemini Observatory 100 The year-end task included) have extremely dedicated and hard- completion statistics 90 working staff members striving to achieve a across the entire M 80 0-49% Done observatory are worthwhile goal. -

Chapter 1: How the Sun Came to Be: Stellar Evolution

Chapter 1 SOLAR PHYSICS AND TERRESTRIAL EFFECTS 2+ 4= Chapter 1 How the Sun Came to Be: Stellar Evolution It was not until about 1600 that anyone speculated that the Sun and the stars were the same kind of objects. We now know that the Sun is one of about 100,000,000,000 (1011) stars in our own galaxy, the Milky Way, and that there are probably at least 1011 galaxies in the Universe. The Sun seems to be a very average, middle-aged star some 4.5 billion years old with our nearest neighbor star about 4 light-years away. Our own location in the galaxy is toward the outer edge, about 30,000 light-years from the galactic center. The solar system orbits the center of the galaxy with a period of about 200,000,000 years, an amount of time we may think of as a Sun-year. In its life so far, the Sun has made about 22 trips around the galaxy; like a 22-year old human, it is still in the prime of its life. Section 1.—The Protostar Current theories hold that about 5 billion years ago the Sun began to form from a huge dark cloud of dust and vapor that included the remnants of earlier stars which had exploded. Under the influence of gravity the cloud began to contract and rotate. The contraction rate near the center was greatest, and gradually a dense central core formed. As the rotation rate increased, due to conservation of angular momentum, the outer parts began to flatten. -

(NASA/Chandra X-Ray Image) Type Ia Supernova Remnant – Thermonuclear Explosion of a White Dwarf

Stellar Evolution Card Set Description and Links 1. Tycho’s SNR (NASA/Chandra X-ray image) Type Ia supernova remnant – thermonuclear explosion of a white dwarf http://chandra.harvard.edu/photo/2011/tycho2/ 2. Protostar formation (NASA/JPL/Caltech/Spitzer/R. Hurt illustration) A young star/protostar forming within a cloud of gas and dust http://www.spitzer.caltech.edu/images/1852-ssc2007-14d-Planet-Forming-Disk- Around-a-Baby-Star 3. The Crab Nebula (NASA/Chandra X-ray/Hubble optical/Spitzer IR composite image) A type II supernova remnant with a millisecond pulsar stellar core http://chandra.harvard.edu/photo/2009/crab/ 4. Cygnus X-1 (NASA/Chandra/M Weiss illustration) A stellar mass black hole in an X-ray binary system with a main sequence companion star http://chandra.harvard.edu/photo/2011/cygx1/ 5. White dwarf with red giant companion star (ESO/M. Kornmesser illustration/video) A white dwarf accreting material from a red giant companion could result in a Type Ia supernova http://www.eso.org/public/videos/eso0943b/ 6. Eight Burst Nebula (NASA/Hubble optical image) A planetary nebula with a white dwarf and companion star binary system in its center http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap150607.html 7. The Carina Nebula star-formation complex (NASA/Hubble optical image) A massive and active star formation region with newly forming protostars and stars http://www.spacetelescope.org/images/heic0707b/ 8. NGC 6826 (Chandra X-ray/Hubble optical composite image) A planetary nebula with a white dwarf stellar core in its center http://chandra.harvard.edu/photo/2012/pne/ 9. -

SEEDS – Direct Imaging Survey for Exoplanets and Disks

SEEDS – Direct Imaging Survey for Exoplanets and Disks K. G. Helminiak 1,2, M. Kuzuhara3,4, T. Kudo3, M. Tamura3,5, T. Usuda1, J. Hashimoto6, T. Matsuo7, M. W. McElwain8, M. Momose9, T. Tsukagoshi9, and the SEEDS/HiCIAO team 1Subaru Telescope, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, 650 North Aohoku Place, Hilo, HI 96720, USA 2Nicolaus Copernicus Astronomical Center, Department of Astrophysics, ul. Rabia´nska 8, 87-100 Toru´n,Poland 3National Astronomical Observatory Japan (NAOJ), Osawa 2-21-1, Mitaka, Tokyo 181-8588, Japan 4Department of Earth and Planetary Science, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2-12-1 Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo 181-8588, Japan 5School of Science, The University of Tokyo, Hongo 7-3-1, Bunkyo, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan 6Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Oklahoma, 440 West Brooks Street, Norman, OK 73019, USA 7Department of Astronomy, Kyoto University, Kitashirakawa-Oiwake-cho, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan 8Exoplanets and Stellar Astrophysics Laboratory, Code 667, Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA 9College of Science, Ibaraki University, Bunkyo 2-1-1, Mito 310-8512, Japan Abstract. Exoplanets on wide orbits (r & 10 AU) can be revealed by high-contrast direct imaging, which is efficient for their detailed detections and characterizations compared with indirect techniques. The SEEDS campaign, using the 8.2-m Subaru Telescope, is one of the most extensive campaigns to search for wide-orbit exoplanets via direct imaging. Since 2009 to date, the campaign has surveyed exoplanets around stellar targets selected from the solar neighborhood, moving groups, open clusters, and star- 750 SEEDS–DirectImagingSurveyforExoplanetsandDisks forming regions. -

Stellar Properties of Embedded Protostars

Stellar Properties of Embedded Protostars R. J. White University of Alabama in Huntsville T. P. Greene National Aeronautics and Space Administration at Ames Research Center G. W. Doppmann Gemini Observatory K. R. Covey University of Washington L. A. Hillenbrand California Institute of Technology Protostars are precursors to the nearly fully assembled T-Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be type stars undergoing quasi-static contraction towards the zero-age main sequence; they are in the process of acquiring the majority of their stellar mass. Although numerous young stars with spatially extended envelope-like structures appear to fit this description, their high extinction has inhibited observers from directly measuring their stellar and accretion properties and confirming that they are in fact in the main phase of mass accretion (i.e., true protostars). Recently, however, high dispersion spectrographs on large aperture telescopes have allowed observers to begin studying the stellar and accretion properties of a subset of these stars, commonly referred to as Class I stars. In this Chapter, we summarize the newly determined properties of Class I stars and compare them with observations of Class II stars, which are the more optically revealed T Tauri stars, to better understand the relative evolutionary state of the two classes. Class I stars have distributions of spectral types and stellar luminosities that are similar to those of Class II stars, suggesting similar masses and ages. The stellar luminosity and resulting age estimates, however, are especially uncertain given the difficulty in accounting for the large extinctions, scattered light emission and continuum excesses typical of Class I stars. -

The Variability of Young Stellar Objects

448 Herbst, JAAVSO Volume 40, 2012 The Variability of Young Stellar Objects William Herbst Astronomy Department, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT 06459; [email protected] Invited review paper, received February 15, 2012 Abstract A brief review of the types and causes of the variability of young stellar objects (pre-main sequence stars) is given with an emphasis on what we do not yet understand and how amateur observers can continue to make important contributions to the field. 1. Introduction Alfred H. Joy (1945) was the first to identify a class of eleven irregular variable stars with characteristics similar to his adopted proto-type T Tauri. The amplitude of the variability was large—typically several magnitudes—and irregular, with no evidence of periodicity and no discernible pattern. Some stars behaved erratically, changing brightness by a magnitude or more from night to night, while others were more quiescent. Individual stars went through active periods and quiescent periods, although some could be counted on to generally be more active than others. The close association of these stars with dark and bright nebulosity as well as their spectroscopic characteristics, including emission lines of CaII and HI, indicated that they might be very young stars, an hypothesis more or less proven by George Herbig (1960, 1962). There are now thousands of known T Tauri stars within reach of small telescopes. Many were discovered by their Ha emission and catalogued by Herbig and Bell (1988). Others were found in photometric studies, especially of young clusters such as the Orion Nebula Cluster (Herbst et al. 2002). The range of spectral classes among the original eleven stars of Joy was rather narrow and did not extend later than G5. -

Spectral Evidence of Abundant Silica Created by a Massive In-System Collision? - C.M

Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIX (2008) 2119.pdf Star System HD172555 - Spectral Evidence of Abundant Silica Created by a Massive In-System Collision? - C.M. Lisse1,C. H. Chen2, M. C. Wyatt3, and A. Morlok4. 1 JHU-APL, 11100 Johns Hopkins Road, Laurel, MD 20723 [email protected]. 2NOAO, 950 North Cherry Avenue, Tucson, AZ 85719 [email protected]. 3Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK [email protected]. 4CRPG-CNRS, UPR2300, 15, rue Notre Dame des Pauvres, BP20, 54501 Vandoeuvre les Nancy, France amor- [email protected] Introduction: HD172555 is an A5 IV/V star at 29.2 pc from the Earth, and as a member of the β Pic mov- ing group, is estimated to be very young, ~12Myr [1]. What makes this star system stand out initially is the large amount of IR-radiation coming from it : in terms of the fractional luminosity of the dust, f/fmax is ~100 [2], which is quite extreme compared to the IR emis- sion found around other A stars, even those with cir- cumstellar disks. The overall spectral energy distribu- tion (Figure 1) has a best-fit blackbody temperature of ~260K, which means the dust is relatively warm and located at around 3-4AU from the primary. The system Figure 2 - Spitzer IRS spectrum of HD 17255 excess. also contains a wide binary companion, an M0 star CD -64 1208 at ~2000AU, and while the companion may What makes the system really interesting is the dynamically limit the extent of any large dust orbits, it shape of the spectral features (or lack thereof) in the 5- is not important with respect to the energy budget of the warm dust.