Centering Aesthetically Within Place: a Geostory Composed from an Arts-Based Pragmatist Inquiry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Marvel Comics Collection by Chi WOW WOW Hits the Streets for Fall Dog Fashion

Press Release The Marvel Comics Collection by Chi WOW WOW Hits the Streets for Fall Dog Fashion ALTADENA, Calif., August 29, 2007 – Chi WOW WOWTM, an internationally known designer and manufacturer of pet apparel, announced today that its Marvel Comics Collection will be available on retailer shelves next month. Chi WOW WOW signed a licensing agreement with Marvel Entertainment, Inc. as a pet apparel and accessories licensee earlier this year, to expand its already popular pet product lines, Chi WOW WOW Vintage and Signature Collections and IZZY GALORE. Chi WOW WOW was awarded the rights to produce its product line for several premier Marvel character franchises, including Spider-Man, X- Men, Fantastic Four, The Incredible Hulk, Silver Surfer and Captain America. The initial product assortment includes pet t-shirts, tanks, reversible hooded sweatshirts (image below), collars and beds. Chi WOW WOW got its start making tees for dogs out of vintage and re-cycled clothing. The very first tee was made for her 4 lb. rescued Chihuahua, ELVIS, from a vintage 1970 Captain America t-shirt that the owner, Carolyn Paxton, still had in her possession from the age of 11. “Marvel fits very well into our image and brand recognition. We are known for our tomboyish and funky streetwear; how perfect to be putting the retro Super Heroes I loved as a kid, now on clothes for dogs”, quoted Ms. Paxton, back in March. # # # About Marvel Entertainment, Inc. With a library of over 5,000 high-profile characters built over more than sixty years of comic book publishing, Marvel Entertainment, Inc. -

Winter/Spring 2017

WINTER/SPRING 2017 WINTER I GLADYS DOUGLAS SCHOOL FOR THE ARTS DUNEDIN, FLORIDA January 9 – February 19 WINTER II studio art classes and workshops February 20 – April 2 for children, teens & adults SPRING April 10 – May 21 www.dfac.org CONTACT Tel. 727.298.3322 • Fax 727.298.3326 • e-mail: [email protected] • www.dfac.org HOURS Galleries and Gift Shop: Monday–Friday • 10am–5pm Saturday • 10am–2pm Sunday • 1pm–4pm GLADYS DOUGLAS SCHOOL FOR THE ARTS Evening hours limited to enrolled students. There are designated disabled parking spaces near the entry and 1143 Michigan Boulevard, Dunedin, Florida 34698 there is easy access to and throughout the Center and Palm Cafe. DFAC is a handicapped accesible facility. DUNEDIN FINE ART BOARD OF DIRECTORS CENTER STAFF OFFICERS: Ingrid Allegretta Visitor Services Amy Heimlich Board Chair contents David Barton Accounting Manager London L. Bates daily class calendar ............................... 2 Vice-Board Chair Catherine Bergmann daily workshop calendar ....................... 4 Curatorial Director Sarah Byars Secretary life arts ................................................... 6 George Ann Bissett President / CEO Lorri Kidder jewelry .................................................... 8 Treasurer Debra Blythe stone carving and wood turning ........ 10 Gift Shop / Database Admin. Alison Freeborn Parliamentarian metal arts ............................................ 10 Mary Danikowski Visitor Services Walter W. Blenner, Esq. mixed media ......................................... 11 Immediate Past -

Dobdrman Secrets

DobermanDoberman SecretsSecrets RevealedRevealed Love, Life and Laughter. With a Doberman The author has made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information in the e book. The information provided “as is” with all faults and without warranty, expressed or implied. In no event shall the author be liable for any incidental or consequential damages, lost profits, or any indirect damages. The reader should always first consult with an animal professional. Doberman Secrets Revealed Table Of Contents Topic Page No Foreword 3 Chapter 1.Buying A Doberman 4 Chapter 2. The First Paw-Marks 10 Chapter 3. Choose Your Dobe 12 Chapter 4.An Addition To The Family 19 Chapter 5. Follow The Leader 35 Chapter 6.Protect Him, So He Can Protect You 50 Chapter 7.Doctor, This Is An Emergency 70 Chapter 8. Golden Years 72 Chapter 9. Spaying & Neutering 81 2 Foreword Whoever coined the phrase ‘man’s best friend’ must have had the Doberman in mind. Because, you will not find a better companion in any other breed. It’s long list of qualities (and trust us, if trained right, these will surface) seems a little too perfect. But only a Doberman can lay claim to every one of them. A Doberman is a sensitive dog, keenly alert to your feelings and wishes. He is fiercely loyal, protective to a very high degree and will love you back tenfold. Observe him when someone you like visits you. Again, observe him when someone you don’t particularly care for, visits you. He will be watching the visitor hawk-eyed. -

Woof-A-Palooza Is a One Mile Dog Walk to Benefit Chatham Animal Rescue & Education, Inc

Thank you ... What is Woof? How to Woof? 3rd Annual Woof-A-Palooza is a one mile dog walk to benefit Chatham Animal Rescue & Education, Inc. Register for Woof-A-Palooza (C.A.R.E.). There will be prizes, refreshments, vendors, contests and other activities for you Return the attached registration and your pet. form. Registration fees: $25 per dog Dog Walk, Contests & Fun Mail in your registration by your Why Woof? September 3rd and pay discounted Early Bird Registration fee: $20 per dog All the animals in the C.A.R.E. system are fostered Recruit support! in volunteer foster homes. C.A.R.E. provides both routine medical care such as vaccinations, Ask relatives, friends and co-workers to join deworming, and spay/neuter and more you on your walk or sponsor you to walk. extraordinary medical care such as heartworm Walk together, bring your pets and enjoy the All proceeds benefit treatment and special needs operations. day! Don’t worry if you don’t have a dog... you can walk one of Charlotte While adoption fees cover much of the very basic Our 2004 Woof Spokesdog medical care, they do not cover additional our fosters. treatments that some animals require. We count on events like this to help fund additional treatment Collect for animals with special needs. C.A.R.E. wants to take time to say thank you for your help and www.chathamanimalrescue.org support. Get some sponsors for your walk! Use the Donation form to collect for the animals. When is Woof? Walk Saturday, September 18, 2004 10:00am - 2:00pm - Rain or Shine Come, walk and enjoy the day! Enter our contests. -

Dog Bites: Perception and Prevention

DOG BITES: PERCEPTION AND PREVENTION Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Sara Cecylia Owczarczak-Garstecka. 22 April 2020 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 8 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................... 10 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 11 1.1 On nature (and culture) of dog bites .................................................................................... 11 1.2 Context of the study ............................................................................................................. 13 Changing welfare of dogs .............................................................................................. 13 Changing relationships with dogs ................................................................................. 14 Changing expectations of dogs ..................................................................................... 16 Context of bite prevention ............................................................................................ 17 Dog bites in Liverpool................................................................................................... -

Ethics Scenarios

Scenario Cards Module 9, Lesson 9 Issues and Ethical Consideraons Dog Meat An annual dog meat celebraon is held each June in Yulin, Guangxxi, China. This tradi7on has been in prac7ce for over 400 years. It was believed that eang dog meat would ward off the heat felt through the summer months. Dogs are placed in crates and cages, paraded for viewing before they are prepared for consump7on. 10,000-15,000 dogs are consumed during the 10-day fes7val. Dog-meat dish from Guilin. Tail used as decoraon. Dog meat is a regular item on menus in Korea, China, Indonesia, Mexico, Philippines, Polynesia, Taiwan, Vietnam, Switzerland, the Arc7c and Antarc7c. Dog Shows Described as celebrang the poten7al inherent in dogs of all breeds and backgrounds. Show ac7vi7es can include a variety of tests: -Field trials -Herding tests -Appearance and structure Dog shows can be local, naonal or internaonal. Dogs are oVen bred for par7cipaon. Dying dog hair Hair dye is designed for humans, not for dogs. Chemicals in the dye can increase risk of chemical burns and skin irritaon. Some dogs can experience allergic reac7ons to the dye. Should the dog try to lick its coat during the process, toxic dye can be ingested, leading to nausea, vomi7ng, diarrhea and other more serious health issues. People dye their hair for cosme7c reasons. Dogs do not have this same need. Dog fashion Fashion trends date back to collars from the Egyp7an pre-dynas7c period. Photographs from the early 1900s show people dressing their dogs in human costumes. Dog fashion has become increasingly popular since 2011 with clothing choices available in a variety of designer styles. -

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Exploring Instagram

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Exploring Instagram Marketing Strategy for Direct Message Sellers in the Pet Fashion A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Science in Apparel Design and Merchandising By Beverly Chiang August 2020 Signature Page The thesis of Beverly Chiang is approved: ______________________________________ ________________________ Wei Cao, Ph.D. Date ______________________________________ ________________________ Hira Cho, Ph.D. Date ______________________________________ ________________________ Tracie Tung, Ph.D., Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Acknowledgments My dog Ted inspires me about Pet Fashion. It has been my passion to explore different pet clothes and accessories. I would like to thank Dr. Tung for assisting me with an interesting topic and for providing me many ideas to complete this thesis project. Thank you for your enthusiasm, encouragement, and support, which has been significant to me and my project. Thank you, Dr. Cho and Dr. Cao, my committee, for your consideration and suggestions. Lastly, I would like to thank my parents. Thank you very much for all the support and encouragement throughout my study. I am very grateful for this project, which offered me the opportunity to examine how to create a social media business in Pet Fashion. My goal is to bring the Pet Fashion to the world. iii Table of Contents Signature Page ................................................................................................................................ -

Your Comprehensive Guide to the State of the Pet Industry

January 2016 2015-2016 RETAILER Your Comprehensive Guide to REPORTthe State of the Pet Industry PetAge_010116_Cover.indd 1 12/23/2015 4:42:51 PM [email protected] www.sherpapet.com PetAge_010116_Cover.indd 2 12/23/2015 4:42:52 PM JANUARY 2016 VOL 45 NO. 16 Pet Age Features 35 2015-2016 Pet Age Retailer Report The results of the pet age retailer survey are in. 34 Automating Your Inventory Better inventory management can boost profits. 30 To Borrow or not to Borrow? How to avoid some of the pitfalls of financing a store. Also in this issue 2 Publisher’s Letter 48 Trends and Products 74 Community Dog: Flea and tick; Treats and chews 4 Editor’s Letter Cat: Wet and moist foods; 80 Backstory: Petfood Forum Senior cat care 8 Storefront Aquatics: Freshwater fish; Pond opening 24 Stockroom Reptile: Heating and lighting New Products Bird: Grooming Focus On: Pet outdoor wear Small Animal: Chinchilla products Natural: Products from the sea 30 Management Groom and Board: Nail care Creating an events calendar Good treats for dog training January 2016 petage.com 1 PetAge_010116_Pub-EditorLetter_TOC.indd 1 12/23/2015 5:24:06 PM ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ EARLY BIRD ▲ ▲ Publisher’s Letter ▲ Where the Global ▲ ▲ ▲ SPECIAL – ▲ Pet Age ▲ ▲ ▲ EXECUTIVE PUBLISHER ▲ Allen Basis ▲ Pet Food Industry ▲ [email protected] ▲ 732-246-5706 ▲ ▲ SAVE ▲ VICE PRESIDENT AND PUBLISHER ▲ Craig M. Rexford ▲ ▲ [email protected] ▲ ▲ Think Ahead ▲ 732-246-5709 ▲ Does Business ▲ ▲ ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES ▲ $220!▲ Trade show season is on the horizon. Ariyana Edmond ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ [email protected] ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ 323-868-5038 ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ven though trade shows happen ev- as soon as possible to avoid last minute Ric Rosenbaum ▲ ery year, they always seem to arrive mix-ups. -

Your Dog's Health Preventive Care

Your dog's health Preventive care Good preventive care begins with careful attention to the basics: Nutrition A healthy, nutritious diet builds a foundation for well-being and disease prevention throughout your Pet's life. As a dog ages, their nutritional needs change; for example, a puppy needs a diet high in calories and protein to maintain its active lifestyle and to grow healthy bones and muscles. An older dog may need a diet restricted in calories and supplemented with fiber for optimum weight and gastrointestinal health. Nutritional counseling is a vital component of your Pet's healthcare–and a part of a discussion with your veterinarian. We can help you decide which food is best for your Pet during each life stage. Vaccinations Vaccinations protect dogs from many viral and bacterial predators, including parvovirus, corona virus, leptospirosis, adenovirus, parainfluenza virus, and distemper. These organisms cause a wide range of disease symptoms, from sneezing to bloody diarrhea and death. Just like a child, your puppy needs to be protected at an early age and given boosters as an adult. Vaccinations are one of mankind's greatest medical achievements and can help your Pet live a longer, healthier life–so why take the chance? Parasite control Many types of worms can affect your Pet, and some can be contagious to you and your family. Worms attach to the intestinal lining, causing painful diarrhea or life-threatening conditions. They also compete for your Pet's nutrients, stunting growth and depriving your Pet of energy. Worms live inside your Pet, so it may not be obvious that your dog is suffering an infestation. -

Journal 15,2.Qxp

THE NORTH CAROLINA STATE BAR SUMMER JOURNAL2010 IN THIS ISSUE Addressing the Advocacy Gap page 8 Recent Developments in North Carolina Animal Law page 10 Bad Faith in North Carolina Insurance Contracts page 23 Addressing the Advocacy Gap— Medicaid Recipients Filing for Medicaid Benefits B Y A NN S HY First the good news… recipient, the administrative law There are several particularly good things judge's decisions are reviewed by about Medicaid in North Carolina. For one, the Department of Health and we have traditionally had some of the highest Human Services (DHHS), home reimbursement rates in the country for health- to the Medicaid Agency. This is care providers serving Medicaid recipients.1 analogous to courtroom defen- That translates into more providers and better dants having the power to over- access to services for recipients. Another high- turn judges who rule against light is that the state has implemented a medi- them. Technically, the Medicaid ation program2 whereby roughly 80% of all Agency can only reject the claims brought for Medicaid benefits by recip- administrative law judge's ruling ients are resolved through mediation, eliminat- if the findings of fact are clearly ing the need for an administrative hearing contrary to the evidence present- before an administrative law judge.3 ed in the hearing. This may seem Approximately ten percent of claims are dis- like a limitation on the Medicaid missed, either because of post-mediation set- Agency's power to overturn deci- tlement or because the party dropped the case sions; however, 81% of all deci- (for reasons not examined here). -

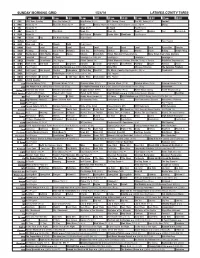

Sunday Morning Grid 1/31/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/31/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding College Basketball Maryland at Ohio State. (N) PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Collinsworth Mecum Main Attractions International Auto Show 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Rock-Park Explore NBA Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 700 Club Telethon 11 FOX Fox News Sunday Paid Tip-Off College Basketball Villanova at St. John’s. (N) Big East Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Celtic Thunder 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage (TV14) Å Leverage Å Leverage (TV14) Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Puebla República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Hocus Pocus ›› (1993) Bette Midler. -

Sunday Morning Grid 1/24/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/24/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Auto Racing (N) Å NFL Champ. Chase The NFL Today (N) Å Football 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Hockey Pittsburgh Penguins at Washington Capitals. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Paid Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage The Radio Job. Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Puebla República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Dennis the Menace ›› (1993) Walter Matthau.