Britain's First Community Orthodontic Scheme: for the Children of Heston and Isleworth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 31 No.1 March 2013

WEST MIDDLESEX FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY JOURNAL _____________________ Vol. 31 No.1 March 2013 WEST MIDDLESEX FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY Executive Committee Chairman Mrs. Pam Smith 23 Worple Road, Staines, Middlesex TW18 1EF [email protected] Secretary Richard Chapman Golden Manor, Darby Gardens Sunbury-on-Thames, Middlesex TW16 5JW [email protected] Treasurer Ms Muriel Sprott 1 Camellia Place, Whitton, Twickenham, Middlesex TW2 7HZ [email protected] Membership Mrs Betty Elliott Secretary 89 Constance Road, Whitton, Twickenham Middlesex TW2 7HX [email protected] Programme Mrs. Kay Dudman Co-ordinator 119 Coldershaw Road, Ealing, London W13 9DU Bookstall Manager Mrs. Margaret Cunnew 25 Selkirk Road, Twickenham, Middlesex TW2 6PS [email protected] Committee Members Claudette Durham, Dennis Marks, Joan Storkey Post Holders not on the Executive Committee Editor Mrs. Bridget Purr 8 Sandleford Lane, Greenham, Thatcham, Berks RG19 8XW [email protected] Projects Co-ordinator Brian Page 121 Shenley Avenue, Ruislip, Middlesex HA4 6BU Society Archivist Yvonne Masson Examiner Paul Kershaw Society Web site www.west-middlesex-fhs.org.uk Subscriptions All Categories: £12 per annum Subscription year 1 January to 31 December If you wish to contact any of the above people, please use the postal or email address shown. In all correspondence please mark your envelope WMFHS in the upper left-hand corner; if a reply is needed, a SAE must be enclosed. Members are asked to note that receipts are only sent by request, if return postage is included. Published by West Middlesex Family History Society Registered Charity No. -

Street Name Tree Species/Job Instructions Location Ward ALBURY AVENUE Carpinius Betulus Fastigiata Plant in Grass Verge Outside

Street Name Tree Species/Job Instructions Location Ward Carpinius betulus fastigiata plant Isleworth and ALBURY AVENUE in grass verge Outside 3-5 Brentford Area Carpinus bet.Fastigiata(clear stem) plant in excisting tree pit, Isleworth and ALBURY AVENUE grub out dead sampling. Os 12-14 Brentford Area Plant Sorbus thur. Fastigiata opposite 10 and install new tree ALKERDEN ROAD pit Os 04/06 Chiswick Area Plant Sorbus thur. Fastigiata and ALKERDEN ROAD install new tree pit Os 4-6 Chiswick Area Plant a Sorbus thur. Fastigiata opposite 10 and install new tree ALKERDEN ROAD pit Os 10 Chiswick Area Please plant new Prunus maackii on excisting grass O/S 16 on the O/S 16 on the green plant new Heston and ALMORAH ROAD green Prunus maackii Cranford Area Please plant new Prunus maackii O/S 17 plant new Prunus Heston and ALMORAH ROAD tree on excisting grass O/S 17 maackii tree on excisting grass Cranford Area O/S 21 please plant new O/S 21 Please plant new Prunus Prunus maackii tree on the Heston and ALMORAH ROAD maackii tree on the green grass on the green Cranford Area Please plant new Prunus maackii tree O/S 20-21 on the green on O/S 20-21Please plant new Heston and ALMORAH ROAD excisting grass Prunus maackii tree on grass Cranford Area Please plant new Prunus maackii on excisting grass O/S 16 on the O/S 16 on the green plant new Heston and ALMORAH ROAD green Prunus maackii Cranford Area Transplant Prunus maackii centrally in excisting grass verge O/S 17-21. -

Our Feltham Rediscovering the Identity of a Post-Industrial Town

London Borough of Hounslow ৷ Feltham ৷ 2019 Our Feltham Rediscovering the Identity of a Post-Industrial Town An Interactive Qualifying Project Report submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by: Meredith Forcier ৷ BME ৷ ‘20 Hannah Mikkila ৷ ME ৷ ‘20 Kyle Reese ৷ RBE/CS ৷ ‘20 Jonathan Sanchez ৷ ME/RBE ৷ ‘20 Nicholas Wotton ৷ MA ৷ ‘20 Advisors: Professor Fabio Carrera & Professor Esther Boucher-Yip https://sites.google.com/view/lo19-of/home [email protected] | [email protected] This report represents the work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its website without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, please see http://www.wpi.edu/academics/ugradstudies/project-learning.html Abstract The London Borough of Hounslow is implementing a fifteen-year revitalization plan for Feltham. Through interviews and community engagement, our project highlighted the elements that make up the identity of the town to be incorporated in the next steps in the redesign of the town center. The team created a website that incorporates project deliverables, a comprehensive list of bibliographical sources, an Encyclopedia of important town assets, a walking tour of key elements of town identity, and a promotional video. ii Acknowledgments There were many people who made the completion of this project possible. It has been a long journey since we began work on the project in January 2019, but a few people have been there all along the way to help us. -

Feltham & Heston

FELTHAM AND HESTON LIVER DISEASE PROFILE BACKGROUND LIVER DISEASE IN NUMBERS Liver disease is the third most common Liver disease mortality rates in the UK cause of premature death in the UK and o increased 400% since 19701 the national liver disease health outcomes are worse than in other o £2.1billion per year spent on 1 western European countries. treating liver disease4 Over the last decade, the number of liver o More than 1million admissions to disease-related hospital admissions in hospital per year as a result of alcohol- 2 related disorders1 England has increased by half, placing an ever greater strain on the health service. o 62,000 years of working life lost to Liver disease liver disease every year1 constitutes the Liver disease disproportionally affects the poorest and the most vulnerable in society o Care for patients who died of liver disease third most common and is a major factor in generating socio- rated as less than good in cause of premature economic health inequalities.3 more than half cases5 death in the UK LIVER DISEASE IN FELTHAM AND HESTON The liver disease The rate of hospital admissions MORTALITY RATE due to liver disease in your 549 amongst under-75s in your local area is lower than 7 YEARS OF WORKING LIFE local area is the national average. were lost in your constituency due to 6 liver disease in 2012-14 316 That is more than the number of 17.7 per 100,000 HOSPITAL working years lost due to: Ø Ischaemic heart disease This is lower than ADMISSIONS due to liver disease in Ø Lung cancer the national average your constituency (17.8 per 100,000)7 Ø Colorectal cancer in 2014-158 LIVER DISEASE RISK FACTORS IN FELTHAM AND HESTON ALCOHOL OBESITY VIRAL HEPATITIS Alcohol is the most common cause Obesity is the key risk factor for The number of deaths due to viral 1 of liver disease in England and the non-alcoholic fatty liver disease hepatitis is increasing. -

Spring Grove. (Northern

378 SPRING GROVE. (NORTHERN • Spring Grove continued. Turnbull John, Derwent lodge Scherer Henry C. baker, r Pembroke Ployd Joseph, 3 Heston villas Varley Mrs. Kingsley place, London road Foord Henry Robert, Woodville Vicars William Archdall, The Rallies Spring Grove Estate Office (Giddy & Ford-Webb Charles M.D. The !<'erns Ward Joseph Kilsby, Holmleigh Giddy, agents), London road Fox Ernest Long, St. Laurence Watson Richard, 6 Park villas Tombleson James Bennett M.B., B.ch. Froom Mrs. Vernon house West Edmund, Pendennis oxon. surgeon, medical officer to the Fulwood Thomas, Albemarle lodge Whitehead Henry Hammond, Holland Borough Road Training College & Gentry George, Eamont lodge house divisional surgeon to the police, G-reenwood William LL.D. barrister-at- Whitehouse Mrs. Calstock Overstone house law), Croylands Williams William, Prydderch, Myfyrion Vallon Hy. corn & flour dlr. London rd Halliday Mrs. Sherwood lodge Winter George, Kroonstad Watson Cycle Co. (A. V. Watson, pro Bammond George James, 8 Clifton viis Young Mrs. T. N. 7 Thornbury road prietor), 6 Pembroke pl. London rd Harding Richmond Arthur, Cranmore Watson Maria (Mrs.), Milford hotel P. H. Harrison Fredk. William, Beaumaris COMMERCIAL, London road Har:Pison T. Hugh, Ardmore • Wiggins Alfred Cousins, coffee rooms, Hart George Edwin, ~tation house . A'Bear Henry, nurseryman, London rd 16 Pembroke place, London road Hewson Victor Louis, I Clifton villas Baker William, bootmaker, IB Pem Hill William Henry, The Lindens broke place, London road Rinks Mrs. 3 Beaumont villas Bazeley Albert Uriah, butcher, 7 Pem- The Borough Road Training College Hodges I<'rederick, Salopian cottage broke place, London road for Teachers occupies premises pur HollingsworthDeputy-Surgeon-Genera.l Benham John, basket maker, London rd ehased in rBgo from the London Thomas Smith A.M.D. -

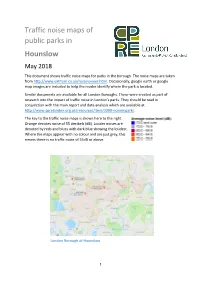

Traffic Noise Maps of Public Parks in Hounslow May 2018

Traffic noise maps of public parks in Hounslow May 2018 This document shows traffic noise maps for parks in the borough. The noise maps are taken from http://www.extrium.co.uk/noiseviewer.html. Occasionally, google earth or google map images are included to help the reader identify where the park is located. Similar documents are available for all London Boroughs. These were created as part of research into the impact of traffic noise in London’s parks. They should be read in conjunction with the main report and data analysis which are available at http://www.cprelondon.org.uk/resources/item/2390-noiseinparks. The key to the traffic noise maps is shown here to the right. Orange denotes noise of 55 decibels (dB). Louder noises are denoted by reds and blues with dark blue showing the loudest. Where the maps appear with no colour and are just grey, this means there is no traffic noise of 55dB or above. London Borough of Hounslow 1 1. Beaversfield Park 2. Bedfont Lake Country Park 3. Boston Manor Park 2 4. Chiswick Back Common 5. Crane Valley Park, South West Middlesex Crematorium Gardens, Leitrim Park 6. Dukes Meadows 3 7. Feltham Park, Blenheim Park, Feltham Arena, Glebelands Playing Fields 8. Gunnersbury Park 9. Hanworth Park 4 10. Heston Park 11. Hounslow Heath 12. Inwood Park 5 13. Jersey Gardens, Ridgeway Road North Park 14. Redlees Park 15. Silverhall Park 6 16. St John’s Gardens 17. Thornbury Park (Woodland Rd) 18. Thornbury Park (Great West Road) 7 19. Turnham Green 20. Lampton Park 21. -

Units 1-10 Aerodrome Way Industrial Estate Heathrow

A WELL ESTABLISHED GREATER LONDON MULTI-LET INDUSTRIAL ESTATE AERODROME WAY INDUSTRIAL ESTATE UNITS 1-10 HEATHROW CRANFORD LANE • HESTON • TW5 9QB INVESTMENT SUMMARY PROPOSAL • A well established Greater London multi- • Freehold. • Two fully refurbished vacant units offered let industrial estate located north-east of with 18-month rent, rates and service charge We are instructed to seek offers in • Let to seven tenants providing attractive Heathrow Airport. guarantees. excess of £14,750,000 (Fourteen income diversity, with no tenant accounting Million, Seven Hundred and Fifty • Aerodrome Way Industrial Estate is well for more than 23% of the rent. • Strong occupational dynamics in the Heathrow Thousand Pounds) subject to positioned 1.4 miles to Junction 3 of the M4, and West London industrial market, with high • Total passing rent of £825,184 per annum contract and exclusive of VAT. A providing excellent access to Central London demand and low supply driving rental growth. (£10.48 per sq ft) including guarantees on purchase at this level would reflect and the national motorway network. Units 1 & 2. • The estate offers value accretive asset a Net Initial Yield of 5.25% and • The estate comprises 78,760 sq ft (7,317 sq management opportunities for a potential • Attractive WAULT of 5.82 years to expiries and a capital value of £187 per sq ft, m), arranged as two terraces with nine units purchaser through the letting of Units 1 & 2, 5.53 years to breaks. assuming purchaser’s costs of 6.73%. ranging from 2,789 sq ft (259.1 sq m) to 12,511 and a medium term refurbishment across sq ft (1,162 sq m), and a stand alone unit of the estate. -

Proposed Additions to the Local List

Proposed Additions to the Local List January 2019 Table of Contents Page number Area Chiswick 3 Brentford 26 Isleworth 36 Hounslow 52 Heston & Cranford 65 Feltham and Bedfont 73 2 Chiswick 3 Image Asset Details Description Address: Homefield Lodge, Lodge which acted as the keeper’s cottage for Chiswick Lane South the Homefield Recreation Ground. It likely dates from the late 19th – early 20th century. Significance: Architectural, The house is made of brick with bargeboards Historical and roof ridge detailing. Reference Number: CH28 Address: Chiswick Baptist Chiswick Baptist Church is a good example of Church, Annandale Road Nonconformist architecture of the late 19th century. The church is ‘a tightly planned, Significance: Architectural, irregular composition’ (Pevsner). It is a red Historical, Social brick three-storey building in gothic style with a pitched slate roof. Chiswick Baptist Church Reference Number: CH29 was designed by John Wills of Derby (1846 - 1906), the foremost architect of non- conformist church buildings of his era. Address: Hogarth Statue, The statue is a one-and-a-quarter-times-life- Chiswick High Road size bronze statue. It shows Hogarth wearing his painting smock and cap and holding his Significance: Architectural, palette and brushes. His pug sits by his side, Historical, Social reminiscent of Hogarth’s self portrait now in the Tate, sculpted by Jim Mathieson. Reference Number: CH30 Hogarth’s main home was in Leicester Square but in 1749 he bought the house in Chiswick that is now known as Hogarth's House and he spent time there for the rest of his life. Hogarth is buried in the family tomb in St Nicholas’ Churchyard, Chiswick. -

Bedfont Brentford

Bedfont Ward Ward Street Name Week Commencing Bedfont Staines Road 23/11/2020 Bedfont Bedfont Green Close 23/11/2020 Bedfont Burlington Close 28/12/2020 Bedfont Hatchett Road 28/12/2020 Bedfont Grovestile Waye 28/12/2020 Bedfont Elm Road 28/12/2020 Bedfont Hatton Road 28/12/2020 Bedfont Bell Lane, Bedfont 28/12/2020 Bedfont Edward Road 28/12/2020 Bedfont Orchard Avenue 28/12/2020 Bedfont Clockhouse Lane 04/01/2021 Bedfont Bedfont Road 04/01/2021 Brentford Ward Ward Street Name Week Commencing Brentford Brook Road South 09/11/2020 Brentford Hamilton Road 09/11/2020 Brentford Clifden Road 09/11/2020 Boston Manor Road (jw Swyncombe to Brentford boundary) 18/01/2021 Brentford Swyncombe Avenue 18/01/2021 Brentford Windmill Road (jw Whitestile Road to A4) 18/01/2021 Brentford Avenue Road 18/01/2021 Brentford Brook Road South 25/01/2021 Brentford Grosvenor Road 25/01/2021 Brentford Windmill Road (jw Boston Manor Road to j/w A 25/01/2021 Brentford Transport Avenue 25/01/2021 Brentford Lateward Road 25/01/2021 Brentford St Pauls Road 25/01/2021 Brentford Albany Road 25/01/2021 Brentford Ferry Lane 25/01/2021 Brentford Lionel Road North 08/02/2021 Brentford Chestnut Avenue 08/02/2021 Brentford Clayponds Avenue 08/02/2021 Brentford South Ealing Road 08/02/2021 Brentford Springvale Avenue 08/02/2021 Brentford Acacia Avenue 08/02/2021 Brentford Almond Grove 08/02/2021 Brentford Cherry Crescent 08/02/2021 Brentford Rowan Road 08/02/2021 Brentford Maple Grove 08/02/2021 Brentford Beech Avenue 08/02/2021 Brentford Hornbeam Crescent 08/02/2021 Brentford -

Starting in a Hounslow School Nursery in September 2018

Starting in a Hounslow School Nursery in September 2018 Apply on time by 4 May 2018 Children born between 1 September 2014 and 31 August 2015 can start in a nursery class attached to a primary or infant school in September 2018. Please apply directly to the school of your choice. 2 Apply online: www.hounslow.gov.uk/admissions Content Introduction 3 School Information 11 Introduction School Map Types of Schools in Hounslow List of schools Understanding the Admissions Process Admission Criteria for Hounslow Community Infant and Primary Schools Oversubscription Admission Criteria for other schools Priority Admission Area (PAA) Late Applications Additional Information 21 Key dates Special Educational Needs Free childcare and early learning entitlement for 2 year olds. Completing your Application 7 Education and statutory school age Closing date for applications Appeals/ Complaints Proof of Address Transfer to reception class Exceptional Medical/Social Need Childhood Immunisations Additional Forms - Supplementary Information Forms Duplicate applications Waiting lists 3 Introduction Universal 15 hours early education Children attend nursery classes for five half days each entitlement week in term-time, either five mornings or five afternoons, depending on the organisation of each school. Children All three and four year olds are entitled to up to 15 hours cannot be admitted to nursery classes before the school of free early education up to 38 weeks a year. This brochure year in which they reach the age of four. provides information about accessing this entitlement in schools. You may choose to access the free entitlement 30 hours free childcare and early education through an Ofsted registered day nursery, pre-school or entitlement for some working families childminder. -

Heston & Cranford Sector Safer Neighbourhood Teams

Heston & Cranford Sector Safer Neighbourhood Teams Cranford Ward Leigh Wagg A/PS 554TX Gregory Price 688TX Emma Wilcox 418TX Alan Hiskett PCSO 7106TX Saadane Mansouri PCSO 7290TX Nicola Martin-Stone PCSO 7294TX 020 82476062 / Mobile: 07843 065902 [email protected] Priorities set by Ward Panel: Priority 1 Burglary Priority 2 Drugs Priority 3 Anti-social behaviour - Youth Priority 4 Motor Vehicle Crime Personnel update - The team is currently at full strength. 554TX Wagg continues as acting sergeant with 977TX moving across to the Heston Central team to perform the same role. 668TX Price has joined he team with 418TX Wilcox on temporary secondment from Feltham. Ward Priorities The Ward priorities remain constant reflecting the views of the Ward panel members and Officers. The next meeting is scheduled for early June with the Ermine Centre on the Meadows Estate at Hounslow West being the likely venue. Priority 1 – Burglary Burglaries as always, remain a problem across the MPS and during March and April the team conducted 26 visits to victims of crime offering crime prevention advice and reassurance. All neighbouring properties in the area were also visited as part of the cocooning process. Page 1 of 7 Burglary hotspots continue to be the subject of a daily briefing analysis supported by foot, cycle and mobile patrols tasked to specific areas as and where necessary. Known offenders are to be visited at their home addresses on a regular basis under the Borough offender management scheme. Priority 2 – Drugs Under the auspices of Operation Hawk, a drug warrant was executed at Swallowfield House resulting in two arrests for possession of class B drugs. -

7550 the LONDON GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 25, 1898. Railway No

7550 THE LONDON GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 25, 1898. Railway No. 1. of Twickenham in the county of Middlesex, Situate partly in the parish of Isleworth commencing at a point on the Hampton- partly in the parish of Heston, and wholl; road in line with the centre line of Sixth in the urban district of Heston-Isleworth, in Cross-Road, passes in n, north-easterly the county of Middlesex, commencing, at a direction along the Hampton-road and The point about 200 feet west of the Hounslow Green, and terminates by a junction with Barracks Station of the Hounslow anc Railway No. 3 at a point in The Green Metropolitan Railway at the eastern about half way between Knowle-road and boundary of Vicarage Parm-laue, passing the London and South Western Railway along the Bath-road to the open spac< bridge over The Green. formed by the junction of the Bath-roac Dated this llth day of November, 1898. and Staines-road with the High-street For the Drake and Gorham Electric Power Hounslow; crossing this space to the wesl and Traction Company, Limited (Pro- of the drinking fountain, and passing into moters of the Order). and along Bell-road, part of Hanworth- ROBERT DAND, Secretary. road, through Lancers-road into and along ASHWELL, BROWNING, and TUT IN, 79, the Whitton-road (Hounslow) over the Queen-street, Cheapside, London, E.G., London and South Western Railway (Loop Solicitors. Line) Bridge close to the Hounslow and Whitton Station into the Hounslow-road, and terminating at a point where the In Parliament.—Session 1899.