The Current Situation of Gangs in El Salvador

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Club Add 2 Page Designoct07.Pub

H M. ADVS. HULK V. 1 collects #1-4, $7 H M. ADVS FF V. 7 SILVER SURFER collects #25-28, $7 H IRR. ANT-MAN V. 2 DIGEST collects #7-12,, $10 H POWERS DEF. HC V. 2 H ULT FF V. 9 SILVER SURFER collects #12-24, $30 collects #42-46, $14 H C RIMINAL V. 2 LAWLESS H ULTIMATE VISON TP collects #6-10, $15 collects #0-5, $15 H SPIDEY FAMILY UNTOLD TALES H UNCLE X-MEN EXTREMISTS collects Spidey Family $5 collects #487-491, $14 Cut (Original Graphic Novel) H AVENGERS BIZARRE ADVS H X-MEN MARAUDERS TP The latest addition to the Dark Horse horror line is this chilling OGN from writer and collects Marvel Advs. Avengers, $5 collects #200-204, $15 Mike Richardson (The Secret). 20-something Meagan Walters regains consciousness H H NEW X-MEN v5 and finds herself locked in an empty room of an old house. She's bleeding from the IRON MAN HULK back of her head, and has no memory of where the wound came from-she'd been at a collects Marvel Advs.. Hulk & Tony , $5 collects #37-43, $18 club with some friends . left angrily . was she abducted? H SPIDEY BLACK COSTUME H NEW EXCALIBUR V. 3 ETERNITY collects Back in Black $5 collects #16-24, $25 (on-going) H The End League H X-MEN 1ST CLASS TOMORROW NOVA V. 1 ANNIHILATION A thematic merging of The Lord of the Rings and Watchmen, The End League follows collects #1-8, $5 collects #1-7, $18 a cast of the last remaining supermen and women as they embark on a desperate and H SPIDEY POWER PACK H HEROES FOR HIRE V. -

Hawkeye, Volume 1 by Matt Fraction (Writer) , David Aja (Artist)

Read and Download Ebook Hawkeye, Volume 1... Hawkeye, Volume 1 Matt Fraction (Writer) , David Aja (Artist) , Javier Pulido (Artist) , Francesco Francavilla (Artist) , Steve Lieber (Artist) , Jesse Hamm (Artist) , Annie Wu (Artist) , Alan Davis (Penciler) , more… Mark Farmer (Inker) , Matt Hollingsworth (Colourist) , Paul Mounts (Colourist) , Chris Eliopoulos (Letterer) , Cory Petit (Letterer) …less PDF File: Hawkeye, Volume 1... 1 Read and Download Ebook Hawkeye, Volume 1... Hawkeye, Volume 1 Matt Fraction (Writer) , David Aja (Artist) , Javier Pulido (Artist) , Francesco Francavilla (Artist) , Steve Lieber (Artist) , Jesse Hamm (Artist) , Annie Wu (Artist) , Alan Davis (Penciler) , more… Mark Farmer (Inker) , Matt Hollingsworth (Colourist) , Paul Mounts (Colourist) , Chris Eliopoulos (Letterer) , Cory Petit (Letterer) …less Hawkeye, Volume 1 Matt Fraction (Writer) , David Aja (Artist) , Javier Pulido (Artist) , Francesco Francavilla (Artist) , Steve Lieber (Artist) , Jesse Hamm (Artist) , Annie Wu (Artist) , Alan Davis (Penciler) , more… Mark Farmer (Inker) , Matt Hollingsworth (Colourist) , Paul Mounts (Colourist) , Chris Eliopoulos (Letterer) , Cory Petit (Letterer) …less Clint Barton, Hawkeye: Archer. Avenger. Terrible at relationships. Kate Bishop, Hawkeye: Adventurer. Young Avenger. Great at parties. Matt Fraction, David Aja and an incredible roster of artistic talent hit the bull's eye with your new favorite book, pitting Hawkguy and Katie-Kate - not to mention the crime-solving Pizza Dog - against all the mob bosses, superstorms -

M AA Teamups.Wps

Marvel : Avengers Alliance team-ups by Team-Up name _ Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. (50 points) = Black Widow / Hawkeye / Mockingbird Ambulancechasers (50 points) = Dare Devil / She Hulk Arachnophobia (50 points) = Spiderman / Black Widow / Spiderwoman Asgard (50 points) = Thor / Sif Assemble (50 points) = Thor / Hulk / Hawkeye / Black Widow / Ironman / Captain America Aviary (50 points) = all Heroes with a Flying ability Best Coast (50 points) = Hawkeye / Mockingbird / War Machine Birds of a Feather (50 points)= Hawkeye / Mockingbird Bloodlust (50 points) = Wolverine / Black Cat / Sif Cat Fight (50 points) = Kitty Pryde / Black Cat Cosplayers (50 points) = Spiderman / Black Cat Defenders (50 points) = Dr.Strange / Hulk Egghead (50 points) = Hulk / Spiderman / Ironman / Mr.Fantastic Fantastic 4 (50 points) = all Fantastic 4 members Frenemies, Assemble (50 points) = Hawkeye / Black Widow Green Giants (50 points) = She-Hulk / Hulk Heroesforhire (50 points) = Luke Cage / Iron Fist Hard and Soft (50 points) = Kitty Pryde / Colossus Hotstuff (50 points) = Phoenix / Human Torch Illuminati (50 points) = Dr.Strange / Mr.Fantastic / Ironman King&Queen (50 points) = Black Panther / Storm Marvelous (50 points) = Phoenix / Ms. Marvel Sibling Rivalry (50 points) = Invisible Woman / Human Torch Tinmen (50 points) = War Machine / Iron Man Tossers (50 points) = Thing / Hulk / She-Hulk / Phoenix X-Force (50 points) = all X-Men members X-lovers (50 points) = Cyclops / Phoenix by Hero name _ Black Cat + Wolverine / Black Cat / Sif = Bloodlust (50 points) Black Cat + Kitty Pryde = Cat Fight (50 points) Black Cat + Spiderman = Cosplayers (50 points) Black Panther + Storm = King&Queen (50 points) Black Widow + Hawkeye / Mockingbird = Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. -

Power Man & Iron Fist

POWER MAN & IRON FIST DANIEL RAND IS IRON FIST, KUNG FU DEFENDER OF THE INNOCENT. LUKE CAGE, SOMETIMES CALLED POWER MAN, HAS SUPERHUMAN STRENGTH AND DURABILITY. HE’S BEEN AN AVENGER, AND IS NOW A HUSBAND AND FATHER. THEY ARE THE HEROES FOR HIRE. EARTH’S HEROES PREVENTED A CATACLYSMIC EVENT THANKS TO AN INHUMAN NAMED ULYSSES WHO CAN SEE THE FUTURE. ACTING ON HIS VISIONS, CAPTAIN MARVEL HAS SAVED LIVES, BUT NOT WITHOUT TERRIBLE COSTS. AS TENSIONS RISE, EARTH’S GREATEST CHAMPIONS MUST MAKE A CHOICE: PROTECT THE FUTURE…OR CHANGE IT? THE BATTLE OVER PREDICTIVE JUSTICE CAME TO DANNY AND LUKE WHEN REFORMED CRIMINALS AND THEIR FAMILIES SOUGHT PROTECTION FROM PREEMPTIVE STRIKE, A GROUP OF VIGILANTES USING THE MYSTERIOUS SOFTWARE AGNITUS TO HUNT ANYONE WITH A CRIMINAL RECORD, AND SOME PEOPLE WITHOUT ONE. WHEN PREEMPTIVE STRIKE RAIDED H4H HEADQUARTERS, THE POLICE INTERVENED. IN THE CONFUSION, DANNY KICKED AN OFFICER WHO WAS PINNING A CLIENT, AND HE WAS TAKEN TO RYKER’S PRISON. NOW LUKE’S IN HIDING, GETTING FED UP WITH INACTION. AND ULYSSES JUST HAD A VISION OF A JAILBREAK. WRITER ARTISTS COLOR ARTIST DAVID WALKER SANFORD GREENE JOHN RAUCH & FLAVIANO LETTERER & PRODUCTION COVER ARTIST VARIANT COVER ARTIST VC’S CLAYTON COWLES SANFORD GREENE PASQUAL FERRY TITLE PAGE DESIGN ASSISTANT EDITOR EDITOR NICHOLAS RUSSELL KATHLEEN WISNESKI JAKE THOMAS EDITOR IN CHIEF CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER PUBLISHER EXECUTIVE PRODUCER AXEL ALONSO JOE QUESADA DAN BUCKLEY ALAN FINE POWER MAN AND IRON FIST No. 8, November 2016. Published Monthly by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. -

NEW THIS WEEK from MARVEL COMICS... Amazing Spider-Man Venom Inc

NEW THIS WEEK FROM MARVEL COMICS... Amazing Spider-Man Venom Inc. Alpha Astonishing X-Men #6 Avengers #674 Black Bolt #8 (LEGACY) Cable Vol. 1 GN Captain America #696 Doctor Strange #382 Gwenpool #23 Hawkeye #13 (LEGACY) Iceman #8 Inhumans Once and Future Kings #5 (of 5) Iron Fist #75 Spider-Man #235 Spirits of Vengeance #3 (of 5) Star Wars Darth Vader #9 Star Wars Vol. 6 GN True Believers Enter the Phoenix ($1 / reprints X-Men #101) True Believers Cyclops & Marvel Girl ($1 / reprints X-Men #48) X-Men Gold #17 NEW THIS WEEK FROM DC COMICS... Bane Conquest #8 (of 12) Batgirl & the Birds of Prey (Rebirth) Vol. 2 GN Batman #36 Batman and Robin Adventures Vol. 2 GN Batman / TMNT II #1 (of 6) Batman White Knight #3 (of 8) Black Lightning #2 (of 6) Bombshells United #7 Cyborg #19 Dastardly & Mutley #4 (of 6) DC Universe 2017 Holiday Special Deadman #2 (of 6) Deathstroke #26 Green Arrow #35 Green Arrow (Rebirth) Vol. 4 GN Green Lanterns #36 Harley & Ivy Meet Betty & Veronica #3 (of 6) Injustice 2 #15 Jetsons #2 Justice League #34 Nightwing #34 Shadow / Batman #3 (of 6) Superman #36 NEW THIS WEEK FROM IMAGE... Extremity #9 Fix #10 Grave Diggers Union #2 Moonstruck #4 No. 1 with a Bullet #2 Paper Girls #18 Paradiso #1 Savage Dragon #229 Scales & Scoundrels #4 Sleepless #1 Stray Bullets Sunshine & Roses #30 Throwaways #10 Violent Love #10 Walking Dead #174 NEW FROM THE OTHER PUBLISHERS... Babyteeth Vol. 1 GN Captain Canuck Year One #1 Chimichanga Sorrow of World's Worst Face #4 (of 4) Faith's Winter Wonderland #1 Fire Force Vol. -

Spider-Woman

DC MARVEL IMAGE ! ACTION ! ALIEN ! ASCENDER ! AMERICAN VAMPIRE 1976 ! AMAZING SPIDER-MAN ! BIRTHRIGHT ! AQUAMAN ! AVENGERS ! BITTER ROOT ! BATGIRL ! AVENGERS: MECH STRIKE 1-5 ! BLISS 1-8 ! BATMAN ! BETA RAY BILL 1-5 ! COMMANDERS IN CRISIS 1-12 ! BATMAN ADVENTURES CONTINUE ! BLACK CAT ! CROSSOVER ! BATMAN BLACK & WHITE 1-6 ! BLACK KNIGHT CURSE EBONY BLADE ! DEADLY CLASS ! BATMAN: URBAN LEGENDS ! BLACK WIDOW ! DECORUM ! BATMAN/CATWOMAN 1-12 ! CABLE ! DEEP BEYOND ! BATMAN/SUPERMAN ! CAPTAIN AMERICA ! DEPARTMENT OF TRUTH ! CATWOMAN ! CAPTAIN MARVEL ! EXCELLENCE ! CRIME SYNDICATE ! CARNAGE BW & BLOOD 1-4 ! FAMILY TREE ! DETECTIVE COMICS ! CHAMPIONS ! FIRE POWER ! DREAMING : WAKING HOURS ! CHILDREN OF THE ATOM ! GEIGER ! FAR SECTOR ! CONAN THE BARBARIAN ! ICE CREAM MAN ! FLASH ! DAREDEVIL ! JUPITERS LEGACY 1-5 ! GREEN ARROW ! DEADPOOL ! KARMEN 1-5 ! GREEN LANTERN ! DEMON DAYS X-MEN 1-5 ! KILLADELPHIA ! HARLEY QUINN ! ETERNALS ! LOW ! INFINITE FRONTIER ! EXCALIBUR ! MONSTRESS ! JOKER ! FANTASTIC 4 ! MOONSHINE ! JUSTICE LEAGUE ! FANTASTIC 4 LIFE STORY 1-6 ! NOCTERRA ! LAST GOD ! GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY ! OBLIVION SONG ! LEGENDS OF DARK KNIGHT ! HELLIONS ! OLD GUARD 1-6 ! LEGION of SUPER-HEROES ! HEROES REBORN 1-7 ! POST AMERICANA 1-6 ! MAN-BAT ! IMMORTAL HULK ! RADIANT BLACK ! NEXT BATMAN: SECOND SON ! IRON FIST Heart of Dragon 1-6 ! RAT QUEENS ! NIGHTWING ! IRON MAN ! REDNECK ! OTHER HISTORY DC UNIVERSE ! MAESTRO WAR & PAX 1-5 ! SAVAGE DRAGON ! RED HOOD ! MAGNIFICENT MS MARVEL ! SEA OF STARS ! RORSCHACH ! MARAUDERS ! SILVER COIN 1-5 ! SENSATIONAL -

Immortal Iron Fist the Complete Collection Volume 1 Pdf Ebook by Ed Brubaker

Download Immortal Iron Fist The Complete Collection Volume 1 pdf ebook by Ed Brubaker You're readind a review Immortal Iron Fist The Complete Collection Volume 1 ebook. To get able to download Immortal Iron Fist The Complete Collection Volume 1 you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite ebooks in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this file on an database site. Ebook Details: Original title: Immortal Iron Fist: The Complete Collection Volume 1 Series: Immortal Iron Fist 496 pages Publisher: Marvel (December 24, 2013) Language: English ISBN-10: 9780785185420 ISBN-13: 978-0785185420 ASIN: 0785185429 Product Dimensions:6.8 x 0.8 x 10.2 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 4311 kB Description: Experience a brand-new kind of Iron Fist story, one steeped in legends and fables stretching back through the centuries! Orphaned as a child and raised in the lost city of Kun-Lun, Danny Rand returned to America as the mystical martial artist Iron Fist - but all his kung fu skills cant help him find his place in the modern world. After learning that... Review: Are you Iron Fist?Jeez, why does everyone keep asking me that --.If you are a person who read Hawkeye #8 and saw the reference and knew what it meant, then you must have read Fraction/Ajas work on Iron Fist years before. If you did not get the reference, you are not alone. Iron Fist has never been a popular character in the Marvel Universe since.. -

Affiliation List

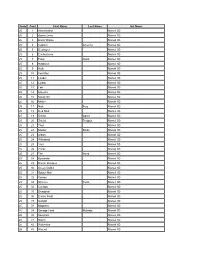

AFFILIATIONS 08/12/21 AFFILIATION LIST Below you will find a list of all current affiliations cards and characters on them. As more characters are added to the game this list will be updated. A-FORCE • She-Hulk (k) • Blade • Angela • Cable • Black Cat • Captain Marvel • Black Widow • Deadpool • Black Widow, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. • Hawkeye • Captain Marvel • Hulk • Crystal • Iron Fist • Domino • Iron Man • Gamora • Luke Cage • Medusa • Quicksilver • Okoye • Scarlet Witch • Scarlet Witch • She-Hulk • Shuri • Thor, Prince of Asgard • Storm • Vision • Valkyrie • War Machine • Wasp • Wasp ASGARD • Wolverine BLACK ORDER • Thor, Prince of Asgard (k) • Angela • Thanos, The Mad Titan (k) • Enchantress • Black Dwarf • Hela, Queen of Hel • Corvus Glaive • Loki, God of Mischief • Ebony Maw • Valkyrie • Proxima Midnight AVENGERS BROTHERHOOD OF MUTANTS • Captain America (Steve Rogers) (k) • Magneto (k) • Captain America (Sam Wilson) (k) • Mystique (k) • Ant-Man • Juggernaut • Beast • Quicksilver • Black Panther • Sabretooth • Black Widow • Scarlet Witch • Black Widow, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. • Toad Atomic Mass Games and logo are TM of Atomic Mass Games. Atomic Mass Games, 1995 County Road B2 W, Roseville, MN, 55113, USA, 1-651-639-1905. © 2021 MARVEL Actual components may vary from those shown. CABAL DARK DIMENSION • Red Skull (k) • Dormammu (k) • Sin (k) DEFENDERS • Baron Zemo • Doctor Strange (k) • Bob, Agent of Hydra • Amazing Spider-Man • Bullseye • Blade • Cassandra Nova • Daredevil • Crossbones • Ghost Rider • Enchantress • Hawkeye • Killmonger • Hulk • Kingpin • Iron Fist • Loki, God of Mischief • Luke Cage • Magneto • Moon Knight • Mister Sinister • Scarlet Witch • M.O.D.O.K. • Spider-Man (Peter Parker) • Mysterio • Valkyrie • Mystique • Wolverine • Omega Red • Wong • Sabretooth GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY • Ultron k • Viper • Star-Lord ( ) CRIMINAL SYNDICATE • Angela • Drax the Destroyer • Kingpin (k) • Gamora • Black Cat • Groot • Bullseye • Nebula • Crossbones • Rocket Raccoon • Green Goblin • Ronan the Accuser • Killmonger INHUMANS • Kraven the Hunter • M.O.D.O.K. -

Form Card First Name Last Name Set Name 25 1 Abomination Marvel 3D

Form Card First Name Last Name Set Name 25 1 Abomination Marvel 3D 25 2 Baron Zemo Marvel 3D 25 3 Black Widow Marvel 3D 25 4 Captain America Marvel 3D 25 5 Destroyer Marvel 3D 25 6 Enchantress Marvel 3D 25 7 Frost Giant Marvel 3D 25 8 Hawkeye Marvel 3D 25 9 Hulk Marvel 3D 25 10 Iron Man Marvel 3D 25 11 Leader Marvel 3D 25 12 Lizard Marvel 3D 25 13 Loki Marvel 3D 25 14 Maestro Marvel 3D 25 15 Maria Hill Marvel 3D 25 16 Melter Marvel 3D 25 17 Nick Fury Marvel 3D 25 18 Red Skull Marvel 3D 25 19 Shield Agent Marvel 3D 25 20 Shield Trooper Marvel 3D 25 21 Thor Marvel 3D 25 22 Master Strike Marvel 3D 25 23 Ultron Marvel 3D 25 24 Whirlwind Marvel 3D 25 25 Ymir Marvel 3D 25 26 Zzzax Marvel 3D 25 27 The Hand Marvel 3D 25 28 Bystander Marvel 3D 25 29 Doctor Octopus Marvel 3D 25 30 Green Goblin Marvel 3D 25 31 Spider-Man Marvel 3D 25 32 Venom Marvel 3D 25 33 Scheme Twist Marvel 3D 25 34 Cyclops Marvel 3D 25 35 Deadpool Marvel 3D 25 36 Emma Frost Marvel 3D 25 37 Gambit Marvel 3D 25 38 Magneto Marvel 3D 25 39 Savage Land Mutates Marvel 3D 25 40 Sentinels Marvel 3D 25 41 Storm Marvel 3D 25 42 Wolverine Marvel 3D 25 43 Wound Marvel 3D 25 44 Egghead Marvel 3D 25 45 Daredevil Marvel 3D 25 46 Elektra Marvel 3D 25 47 Gladiator Marvel 3D 25 48 Punisher Marvel 3D 25 49 Blade Marvel 3D 25 50 Daredevil Marvel 3D 25 51 Elektra Marvel 3D 25 52 Ghost Rider Marvel 3D 25 53 Iron Fist Marvel 3D 25 54 Punisher Marvel 3D 25 55 Blade Marvel 3D 25 56 Daredevil Marvel 3D 25 57 Ghost Rider Marvel 3D 25 58 Iron Fist Marvel 3D 25 59 Punisher Marvel 3D 25 60 Electro Marvel -

AFFILIATION LIST • Black Panther • Black Widow Below You Will Find a List of All Current Affiliations Cards and Characters on Them

AFFILIATIONS 1/08/21 AFFILIATION LIST • Black Panther • Black Widow Below you will find a list of all current affiliations cards and characters on them. As more characters are added to the game • Black Widow, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. this list will be updated. A-FORCE • Captain Marvel • Hawkeye • She-Hulk (k) • Hulk • Angela • Iron Man • Black Widow • She-Hulk • Black Widow, Agent of Shield • Thor, Prince of Asgard • Captain Marvel • Vision • Crystal • Wasp • Domino • Wolverine • Gamora BLACK ORDER • Medusa • Thanos, The Mad Titan (k) • Okoye • Black Dwarf • Scarlet Witch • Corvus Glaive • Shuri • Ebony Maw • Storm • Proxima Midnight • Valkyrie BROTHERHOOD OF MUTANTS • Wasp k ASGARD • Magneto ( ) • Mystique (k) • Thor, Prince of Asgard (k) • Juggernaut • Angela • Quicksilver • Enchantress • Sabretooth • Hela, Queen of Hel • Scarlet Witch • Loki, God of Mischief • Toad • Valkyrie AVENGERS • Captain America (k) • Ant-Man • Beast Atomic Mass Games and logo are TM of Atomic Mass Games. Atomic Mass Games, 1995 County Road B2 W, Roseville, MN, 55113, USA, 1-651-639-1905. © 2021 MARVEL Actual components may vary from those shown. CABAL DEFENDERS • Red Skull (k) • Doctor Strange (k) • Baron Zemo • Daredevil • Bullseye • Ghost Rider • Crossbones • Hawkeye • Enchantress • Hulk • Killmonger • Iron Fist • Kingpin • Luke Cage • Loki, God of Mischief • Spider-Man (Peter Parker) • Magneto • Valkyrie • M.O.D.O.K. • Wolverine • Mystique • Wong • Sabretooth WAKANDA • Ultron • Black Panther (k) CRIMINAL SYNDICATE • Killmonger • Kingpin (k) • Okoye • Black Cat • Shuri • Bullseye • Storm • Crossbones GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY • Green Goblin • Star-Lord (k) • Killmonger • Angela • M.O.D.O.K. • Drax the Destroyer • Mysterio • Gamora • Taskmaster • Groot • Nebula • Rocket Raccoon • Ronan the Accuser Atomic Mass Games and logo are TM of Atomic Mass Games. -

The Law of Daredevil, Jessica Jones, Luke Cage, Iron Fist and the Defenders

Defending the Defenders The Law of Daredevil, Jessica Jones, Luke Cage, Iron Fist and The Defenders Joshua Gilliland, Esq. Angela Storey, Esq. On the Docket Attorney Ethics Right to Counsel Disbarment Service of Process Self-Defense Insanity Defense Punisher Trial Client Solicitation Duty of Confidentiality Duty of Competency Is Vigilantism Creative Community Service? A lawyer who is convicted of a felony will cease to be an attorney or competent to practice law in New York. NY CLS Jud § 90(4)(a) and (4)(e). Defense of Others A person may...use physical force upon another person when and to the extent he or she reasonably believes such to be necessary to defend himself, herself or a third person from what he or she reasonably believes to be the use or imminent use of unlawful physical force by such other person NY CLS Penal § 35.15. You’ve Been Served! Now Let Me Take a Selfie. Can Father Lantom Be Forced to Testify? “Hope” for the Insanity Defense Did those who were “Kilgraved” not understand: 1) The nature and consequences of their criminal conduct; or 2) Understanding that such conduct was wrong. NY CLS Penal § 40.15. No “Mind Control” Cases Did Karen Page Act in Self Defense? Killing Kilgrave People v Frank Castle What’s Up with the DA Violating the Constitution? Trial Advocacy Did Matt Murdock Violate the Duty of Loyalty? Does the Attorney-Client Privilege Apply to Karen and Frank’s Discussions? Battle of Experts Goal: Expert Establish Frank Castle has form of “Sympathetic Storming” for the Insanity Defense Impeach State Witness or Get Him to Agree What is the Danger of Col. -

Orphan Daniel Rand Earned the Power of the Iron Fist in the Mystical City of K’Un Lun

Orphan Daniel Rand earned the power of the Iron Fist in the mystical city of K’un Lun. As an adult, Danny oversees the Rand Corporation and moonlights as Iron Fist: kung fu defender of the innocent. Prisoner Luke Cage was subjected to experiments that gave him superhuman strength and durability. As Power Man, he’s a hero and an Avenger, and now a husband and father. After years apart, they’re back together as Heroes for Hire. DAVID F. SCOTT MATT VC’s CLAYTON WALKER HEPBURN MILLA COWLES Writer Artist Color Artist Letterer JAMAL TREVOR VON EEDEN & RACHELLE NICHOLAS CAMPBELL ROSENBERG; SCOTT HEPBURN & RUSSELL Cover Artist MATT MILLA; KRIS ANKA Title Page Design Variant Cover Artists KATHLEEN JAKE AXEL JOE DAN ALAN WISNESKI THOMAS ALONSO QUESADA BUCKLEY FINE Assistant Editor Editor in Chief Creative Publisher Executive Editor Chief Officer Producer POWER MAN AND IRON FIST: SWEET CHRISTMAS ANNUAL No. 1, February 2017. Published as a One-Shot by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. BULK MAIL POSTAGE PAID AT NEW YORK, NY AND AT ADDITIONAL MAILING OFFICES. © 2016 MARVEL No similarity between any of the names, characters, persons, and/or institutions in this magazine with those of any living or dead person or institution is intended, and any such similarity which may exist is purely coincidental. $4.99 per copy in the U.S. (GST #R127032852) in the direct market; Canadian Agreement #40668537. Printed in the USA. Subscription rate (U.S. dollars) for 12 issues: U.S.