Daily Southtown Home Page | Search | Weather About Us | Subscription Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Topps Tier One Checklist .Xls

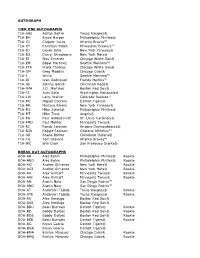

AUTOGRAPH TIER ONE AUTOGRAPHS T1A-ABE Adrian Beltre Texas Rangers® T1A-BH Bryce Harper Philadelphia Phillies® T1A-CJ Chipper Jones Atlanta Braves™ T1A-CY Christian Yelich Milwaukee Brewers™ T1A-DJ Derek Jeter New York Yankees® T1A-DS Darryl Strawberry New York Mets® T1A-EJ Eloy Jimenez Chicago White Sox® T1A-EM Edgar Martinez Seattle Mariners™ T1A-FTA Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox® T1A-GM Greg Maddux Chicago Cubs® T1A-I Ichiro Seattle Mariners™ T1A-IR Ivan Rodriguez Florida Marlins™ T1A-JB Johnny Bench Cincinnati Reds® T1A-JMA J.D. Martinez Boston Red Sox® T1A-JS Juan Soto Washington Nationals® T1A-LW Larry Walker Colorado Rockies™ T1A-MC Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® T1A-MR Mariano Rivera New York Yankees® T1A-MS Mike Schmidt Philadelphia Phillies® T1A-MT Mike Trout Angels® T1A-PG Paul Goldschmidt St. Louis Cardinals® T1A-PMO Paul Molitor Minnesota Twins® T1A-RJ Randy Johnson Arizona Diamondbacks® T1A-RJA Reggie Jackson Oakland Athletics™ T1A-SB Shane Bieber Cleveland Indians® T1A-TG Tom Glavine Atlanta Braves™ T1A-WC Will Clark San Francisco Giants® BREAK OUT AUTOGRAPHS BOA-AB Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie BOA-ABO Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie BOA-AG Andres Gimenez New York Mets® Rookie BOA-AGI Andres Gimenez New York Mets® Rookie BOA-AK Alex Kirilloff Minnesota Twins® Rookie BOA-AKI Alex Kirilloff Minnesota Twins® Rookie BOA-AN Austin Nola San Diego Padres™ BOA-ANO Austin Nola San Diego Padres™ BOA-AT Anderson Tejeda Texas Rangers® Rookie BOA-ATE Anderson Tejeda Texas Rangers® Rookie BOA-AV Alex Verdugo Boston -

2011 Topps Gypsy Queen Baseball

Hobby 2011 TOPPS GYPSY QUEEN BASEBALL Base Cards 1 Ichiro Suzuki 49 Honus Wagner 97 Stan Musial 2 Roy Halladay 50 Al Kaline 98 Aroldis Chapman 3 Cole Hamels 51 Alex Rodriguez 99 Ozzie Smith 4 Jackie Robinson 52 Carlos Santana 100 Nolan Ryan 5 Tris Speaker 53 Jimmie Foxx 101 Ricky Nolasco 6 Frank Robinson 54 Frank Thomas 102 David Freese 7 Jim Palmer 55 Evan Longoria 103 Clayton Richard 8 Troy Tulowitzki 56 Mat Latos 104 Jorge Posada 9 Scott Rolen 57 David Ortiz 105 Magglio Ordonez 10 Jason Heyward 58 Dale Murphy 106 Lucas Duda 11 Zack Greinke 59 Duke Snider 107 Chris V. Carter 12 Ryan Howard 60 Rogers Hornsby 108 Ben Revere 13 Joey Votto 61 Robin Yount 109 Fred Lewis 14 Brooks Robinson 62 Red Schoendienst 110 Brian Wilson 15 Matt Kemp 63 Jimmie Foxx 111 Peter Bourjos 16 Chris Carpenter 64 Josh Hamilton 112 Coco Crisp 17 Mark Teixeira 65 Babe Ruth 113 Yuniesky Betancourt 18 Christy Mathewson 66 Madison Bumgarner 114 Brett Wallace 19 Jon Lester 67 Dave Winfield 115 Chris Volstad 20 Andre Dawson 68 Gary Carter 116 Todd Helton 21 David Wright 69 Kevin Youkilis 117 Andrew Romine 22 Barry Larkin 70 Rogers Hornsby 118 Jason Bay 23 Johnny Cueto 71 CC Sabathia 119 Danny Espinosa 24 Chipper Jones 72 Justin Morneau 120 Carlos Zambrano 25 Mel Ott 73 Carl Yastrzemski 121 Jose Bautista 26 Adrian Gonzalez 74 Tom Seaver 122 Chris Coghlan 27 Roy Oswalt 75 Albert Pujols 123 Skip Schumaker 28 Tony Gwynn Sr. 76 Felix Hernandez 124 Jeremy Jeffress 2929 TTyy Cobb 77 HHunterunter PPenceence 121255 JaJakeke PPeavyeavy 30 Hanley Ramirez 78 Ryne Sandberg 126 Dallas -

2016 PHILADELPHIA PHILLIES (71-91) Fourth Place, National League East Division, -24.0 Games Manager: Pete Mackanin, 2Nd Season

2016 PHILADELPHIA PHILLIES (71-91) Fourth Place, National League East Division, -24.0 Games Manager: Pete Mackanin, 2nd season 2016 SEASON RECAP: Philadelphia went 71-91 (.438) in 2016, an eight-win improvement from the previous year (63 W, .388 win %) … It marked the Phillies fourth consecutive season under .500 (73- PHILLIES PHACTS 89 in both 2013 & 2014, 63-99 in 2015), which is their longest streak since they posted seven consecutive Record: 71-91 (.438) losing seasons from 1994 to 2000 ... The Phillies finished in 4th place in the NL East, 24.0 games behind Home: 37-44 the Washington Nationals, and posted 90 or more losses in a season for the 39th time in club history … Road: 34-47 Philadelphia had 99 losses in 2015, marking the first time they have had 90+ losses in back-to-back Current Streak: Won 1 Last 5 Games: 1-4 seasons since 1996-97 (95, 94) … Overall, the club batted .240 this year with a .301 OBP, .384 SLG, Last 10 Games: 2-8 .685 OPS, 427 extra-base hits (231 2B, 35 3B, 161 HR) and a ML-low 610 runs scored (3.77 RPG) … Series Record: 18-28-6 Phillies pitchers combined for a 4.63 ERA (739 ER, 1437.0 IP), which included a 4.41 ERA for the starters Sweeps/Swept: 6/9 and a 5.01 mark for the pen. PHILLIES AT HOME HOT START, COOL FINISH: Philadelphia began the season with a 24-17 record over their first 41 th Games Played: 81 games … Their .585 winning percentage over that period (4/4-5/18) was the 6 -best in MLB, trailing Record: 37-44 (.457) only the Chicago Cubs (.718, 28-11), Baltimore Orioles (.615, 24-15), Boston Red Sox (.610, 25-16), CBP (est. -

FROM BULLDOGS to SUN DEVILS the EARLY YEARS ASU BASEBALL 1907-1958 Year ...Record

THE TRADITION CONTINUES ASUBASEBALL 2005 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 2 There comes a time in a little boy’s life when baseball is introduced to him. Thus begins the long journey for those meant to play the game at a higher level, for those who love the game so much they strive to be a part of its history. Sun Devil Baseball! NCAA NATIONAL CHAMPIONS: 1965, 1967, 1969, 1977, 1981 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 3 ASU AND THE GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD > For the past 26 years, USA Baseball has honored the top amateur baseball player in the country with the Golden Spikes Award. (See winners box.) The award is presented each year to the player who exhibits exceptional athletic ability and exemplary sportsmanship. Past winners of this prestigious award include current Major League Baseball stars J. D. Drew, Pat Burrell, Jason Varitek, Jason Jennings and Mark Prior. > Arizona State’s Bob Horner won the inaugural award in 1978 after hitting .412 with 20 doubles and 25 RBI. Oddibe McDowell (1984) and Mike Kelly (1991) also won the award. > Dustin Pedroia was named one of five finalists for the 2004 Golden Spikes Award. He became the seventh all-time final- ist from ASU, including Horner (1978), McDowell (1984), Kelly (1990), Kelly (1991), Paul Lo Duca (1993) and Jacob Cruz (1994). ODDIBE MCDOWELL > With three Golden Spikes winners, ASU ranks tied for first with Florida State and Cal State Fullerton as the schools with the most players to have earned college baseball’s top honor. BOB HORNER GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD WINNERS 2004 Jered Weaver Long Beach State 2003 Rickie Weeks Southern 2002 Khalil Greene Clemson 2001 Mark Prior Southern California 2000 Kip Bouknight South Carolina 1999 Jason Jennings Baylor 1998 Pat Burrell Miami 1997 J.D. -

16-0322-Baseball Guide 2016.Pdf

A NOTE FROM THE COLLEGE PRESIDENT ... As spring arrives, so does another great season of competitive intercollegiate baseball on SCC’s beautiful diamond. The Cougars, under the direction of Coach Chris Gober, look forward to another season of excitement and fun after working hard in the off- season. Students, faculty, staff and the community are encouraged to attend our home games. Your support will play a key role in the success of this young and talented baseball team. This season brings new faces both in the lineup and in the classroom, and we look forward to watching the program continue to grow and improve. We wish the Cougar baseball players our best as they work toward a successful season. We know the men will strive to perform equally well in the classroom and on the field. Best Wishes, Ron Chesbrough College President A NOTE FROM THE DIRECTOR OF ATHLETICS ... We start the 2016 season of Cougar baseball with great excitement. The Cougars will face challenging and competitive teams this season as we strive to improve our program. We greatly appreciate the support of our fans. Your encouragement helps us to win games. Our coaches and student-athletes are dedicated to achieving excellence on the field and in the classroom. The athletes are good campus citizens and have been volunteering their assistance with various campus projects. Visit our campus and enjoy some excellent competition between the SCC Cougars and other top-level collegiate teams. You can’t go wrong by rooting for the Cougars. Be sure and wear your maroon and gray to show everyone your Cougar Pride! Best Wishes, Chris Gober Athletic Director 2016 BASEBALL GUIDE 1 About St. -

St. Louis Cardinals (69-65) at Milwaukee Brewers (82-55) Game No

St. Louis Cardinals (69-65) at Milwaukee Brewers (82-55) Game No. 135 • Road Game No. 70 • American Family Field • Sunday, September 5, 2021 LHP Jon Lester (5-6, 5.05) vs. RHP Corbin Burnes (9-4, 2.27) ROAD TRIPPING REDBIRDS: The St. Louis Cardinals conclude their three-game RECORD BREAKDOWN weekend series with the division-rival Milwaukee Brewers this afternoon at CARDINALS vs. BREWERS All-Time Overall ......... 10,237-9,720 American Family Field ... The Redbirds are 5-4 on their 10-game, three-city NL All-Time (1997-2021):............................218-170 2021 Overall ........................... 69-65 Central road trip through Pittsburgh (2-2), Cincinnati (2-1), and Milwaukee (1-1) in St. Louis (1998-2021): ................................ 105-88 Under Mike Shildt ...............231-192 ... The Cardinals enter today in 3rd place in the National League Central, 12.5 at Busch Stadium II (1998-2005): .................. 35-23 Busch Stadium ...................... 35-30 games behind first place Milwaukee and 2.5 games behind Cincinnati for the 2nd at Busch Stadium III (2006-21): ..................... 71-67 Wild Card spot. On the Road ........................... 34-35 in Milwaukee (1998-2021): ..................... 112-80 Day ..........................................25-20 ON DECK: The Cardinals return home to St. Louis on Labor Day for a seven-game at Milwaukee County Stadium (1997-2000): .... 12-10 at American Family Field (2001-21): ....... 100-70 Night ....................................... 44-45 homestand with the Los Angeles Dodgers and division-rival Cincinnati Reds, two teams St. Louis is chasing in the Wild Card race. 2021.....................................................5-6 Spring.................................... 8-10-6 at Busch Stadium ............................................... 2-4 April ......................................... 14-12 ROAD WARRIORS: St. -

Sentimental Tails

Metromix.com: Sentimental tails Monday, July 19, 2004 Weather | Traffic E-mail story Printer Friendly Chicago Maps | classifieds Find a job From the Chicago Tribune Find an apartment Sentimental tails Find a home St. Louis Cardinals manager Tony La Russa let his soft side show when he and Find a car Go shopping his wife founded the Animal Rescue Foundation By Bonnie DeSimone Find a date Place an ad Tribune staff reporter WALNUT CREEK, Calif. -- The gangly 2-year-old collie-shepherd mix looks equal parts wary and hopeful as the man eases into the room with her. channels The dog's name is Kathryn. All the new arrivals at the Animal Rescue Foundation this particular Metromix home week, animals that might have been euthanized by now were it not for ARF, have been given Dining names beginning with K. Like many of them, this dog seems to sense it is auditioning for a new home. Bars & clubs The man has been around hundreds of abandoned Movies animals. He considers them individuals with Music troubled pasts, and he knows the best approach is Events slow and gentle. Dating He reaches toward Kathryn, careful to let the dog see what he's doing. The dog's tail thumps against Theater the floor. Gradually, the man's hand, a hand that Reader reviews has filled out 3,801 major-league baseball lineup cards, comes to rest on her forehead and works Neighborhoods around behind her ears. Party planning The dog is happy, and so is the manager of the St. Louis Cardinals. -

2021 Baltimore Orioles Supplemental Bios

2021 BALTIMORE ORIOLES SUPPLEMENTAL BIOS PLAYERS INCLUDED: NO. 3 MAIKEL FRANCO NO. 35 ADAM PLUTKO FRONT OFFICE INFIELDER MAIKEL FRANCO (Michael Fraun-CO) 3 BATS: Right | THROWS: Right | HEIGHT: 6’1 | WEIGHT: 225 FULL NAME: Maikel Antonio Franco MANAGER & COACHES MANAGER BORN: August 26, 1992 OPENING DAY AGE: 28 BIRTHPLACE: Azua, Dominican Republic RESIDES: Azua, Dominican Republic CONTRACT STATUS: Signed through 2021 MAJOR LEAGUE SERVICE: 5.157 ACQUIRED: Signed by the Orioles as a free agent to a one-year contract on March 16, 2021. maikelfranco1 Maikel franco AWARDS & CAREER-BESTS 2020 HIGHLIGHTS FUTURES GAME SELECTION • Started all 60 games for the Kansas City Royals (51-3B, 8-DH, 1-1B) 2013, 2014 • Led the Royals in doubles (16), extra-base hits (24), and RBI (38); his 62 hits were second- NL ROOKIE OF THE MONTH most on the club June 2015 • Ranked tied for third in the American League in doubles and fourth in two-out RBI (20) • While playing as a third baseman, he recorded 51 hits and 14 doubles, the fifth-most and 2020 IN REVIEW CAREER-BESTS third-most respectively by a third baseman in the majors Hits: 4, 7x, last: 6/23/18 at WSH • Posted a .952 fielding percentage in his 51 games at third base, including turning anAL- Runs: 3, 4x, last: 4/7/18 vs. MIA Doubles: 3, 2x, last: 9/3/16 vs. ATL high 17 double plays as a third baseman Triples: 1, 4x, last: 4/5/18 vs. MIA • Slashed .329/.380/.500 (23-for-70) in the seventh inning-or-later HR: 2, 5x, last: 7/27/20 at DET • Recorded his fifth career multi-home run game, and first since 7/26/18 vs. -

List of MLB Team Nicknames

List of MLB team nicknames Arizona Diamondbacks D-backs – Shorter version of "Diamondbacks". Backs – Shorter version of above. Snakes – Reference to diamondback rattlesnakes. Rattlesnakes – Longer version of above, specifying a type of snake used for the team. Diamondback Rattlesnakes – Even longer version of above, referencing the full name of rattlesnake species used for the team. Scavengers – Used when the team is looking to beat on anyone else. Rakes – Used when the team is raking. Phoenix Diamondbacks – Referring that the team plays home games in Phoenix, AZ. Phoenix D-backs – Shorter version of above. D-bags – Reference to the colloquial insult term douchebag, used by detractors. Diamondsacks – Used by detractors, such as Dodgers and Rockies fans. D-sacks – Same as above. D-sags – Combined variation of "D-bags" and "D-sacks". Atlanta Braves Braves – When the team is not afraid of losing. Bravos – Variation of "Braves". Barves – Another variation of "Braves". Braves Country – Avid followers found primarily throughout the Southeast. Georgia Braves – Referring that the team is located in Georgia. America's Team – Reference to the Braves games being broadcast nationwide. Team of the 90s – Reference to the Braves being the greatest team of the 1990s. Hotlanta Braves – Using pun of city name to refer the team when it is hot. Scary Braves – An oxymoronic pair that refers to the team capable of overpowering anyone. Cowards – Opposite of Braves; used derisively. Coxsuckers – Derogatory reference to the team's long time manager Bobby Cox, used by detractors. Peach Clobbers – Reference to the hard-hitting 2013 Atlanta Braves team. Baby Braves – Reference to the 2018 team that is loaded with really young players like Ronald Acuña Jr., Ozzie Albies, and Dansby Swanson. -

2021 Topps Stadium Club Baseball Checklist

2021 Stadium Club Baseball Autograph Team Player Grid Angels Anthony Rendon Jim Abbott Jo Adell Mike Trout Shohei Ohtani Alex Bregman Andre Scrubb Blake Taylor Brandon Bielak Cristian Javier Enoli Paredes Luis Garcia Nolan Ryan Astros Taylor Jones Yordan Alvarez Athletics Barry Zito Daulton Jefferies Jesus Luzardo Jonah Heim Mark McGwire Ramon Laureano Rickey Henderson Blue Jays Bo Bichette Hyun-Jin Ryu Julian Merryweather Nate Pearson Santiago Espinal Tom Hatch Vladimir Guerrero Jr. Andruw Jones Chipper Jones Cristian Pache Dale Murphy Dansby Swanson Freddie Freeman Greg Maddux Ian Anderson Braves Ronald Acuña Jr. Brewers Christian Yelich Devin Williams Keston Hiura Mark Mathias Cardinals Dylan Carlson Jack Flaherty Jake Woodford Kodi Whitley Nolan Arenado Ozzie Smith Paul Goldschmidt Yadier Molina Cubs Anthony Rizzo Brailyn Marquez Greg Maddux Kerry Wood Kris Bryant Kyle Hendricks Ryne Sandberg Diamondbacks Andy Young Daulton Varsho Clayton Kershaw Cody Bellinger Keibert Ruiz Mitch White Steve Garvey Tony Gonsolin Victor Gonzalez Walker Buehler Dodgers Zach McKinstry Giants Buster Posey Joey Bart Will Clark Indians Andres Gimenez Daniel Johnson Franmil Reyes Kenny Lofton Shane Bieber Triston McKenzie Evan White Ichiro Jarred Kelenic Joey Gerber Ken Griffey Jr. Kyle Lewis Marco Gonzales Randy Johnson Mariners Yohan Ramirez Marlins Jazz Chisholm Jesus Sanchez Lewin Diaz Monte Harrison Nick Neidert Sixto Sanchez Starling Marte Trevor Rogers Ali Sanchez Andres Gimenez Darryl Strawberry David Peterson David Wright Dwight Gooden Franklyn Kilome Jacob deGrom Mets Pete Alonso Nationals Juan Soto Kyle Finnegan Luis Garcia Vladimir Guerrero Orioles Brooks Robinson Cal Ripken Jr. Dean Kremer Eddie Murray Jim Palmer Ryan Mountcastle Padres Eric Hosmer Fernando Tatis Jr. -

2021 Topps Clearly Authentic Baseball Checklist

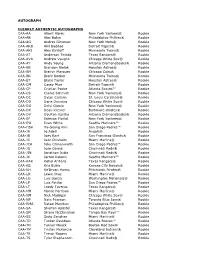

AUTOGRAPH CLEARLY AUTHENTIC AUTOGRAPHS CAA-AA Albert Abreu New York Yankees® Rookie CAA-AB Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie CAA-AG Andres Gimenez New York Mets® Rookie CAA-AKB Akil Baddoo Detroit Tigers® Rookie CAA-AKI Alex Kirilloff Minnesota Twins® Rookie CAA-AT Anderson Tejeda Texas Rangers® Rookie CAA-AVA Andrew Vaughn Chicago White Sox® Rookie CAA-AY Andy Young Arizona Diamondbacks® Rookie CAA-BB Brandon Bielak Houston Astros® Rookie CAA-BM Brailyn Marquez Chicago Cubs® Rookie CAA-BR Brent Rooker Minnesota Twins® Rookie CAA-BT Blake Taylor Houston Astros® Rookie CAA-CM Casey Mize Detroit Tigers® Rookie CAA-CP Cristian Pache Atlanta Braves™ Rookie CAA-CS Clarke Schmidt New York Yankees® Rookie CAA-DC Dylan Carlson St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie CAA-DD Dane Dunning Chicago White Sox® Rookie CAA-DG Deivi Garcia New York Yankees® Rookie CAA-DK Dean Kremer Baltimore Orioles® Rookie CAA-DV Daulton Varsho Arizona Diamondbacks® Rookie CAA-EF Estevan Florial New York Yankees® Rookie CAA-EW Evan White Seattle Mariners™ Rookie CAA-HSK Ha-Seong Kim San Diego Padres™ Rookie CAA-JA Jo Adell Angels® Rookie CAA-JB Joey Bart San Francisco Giants® Rookie CAA-JC Jazz Chisholm Miami Marlins® Rookie CAA-JCR Jake Cronenworth San Diego Padres™ Rookie CAA-JG Jose Garcia Cincinnati Reds® Rookie CAA-JIN Jonathan India Cincinnati Reds® Rookie CAA-JK Jarred Kelenic Seattle Mariners™ Rookie CAA-KAR Kohei Arihara Texas Rangers® Rookie CAA-KB Kris Bubic Kansas City Royals® Rookie CAA-KH Ke'Bryan Hayes Pittsburgh Pirates® Rookie CAA-LD Lewin Diaz Miami Marlins® -

Cincinnati Reds'

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings July 19, 2018 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY 1985-The Reds trade Duane Walker and Jeff Russell to the Rangers for Buddy Bell. Bell will spend four seasons with the Reds, collecting a .266 batting average, with 63 doubles, 43 home runs, 184 RBI and 185 walks with just 118 strikeouts MLB.COM Reds end first half hot, but '19 is still main focus Cincinnati's surge helps avoid need for bigger-scale rebuild; Harvey likely to be flipped By Mark Sheldon MLB.com @m_sheldon Jul. 18th, 2018 CINCINNATI -- It seems quite the contradiction that the Reds are both in fifth place in the National League Central and one of the hottest teams in the Major Leagues. Yet that's exactly where Cincinnati is with a 43-53 record at the All-Star break. The situation is much more optimistic than when the season started. Manager Bryan Price was let go after a 3-15 record, and interim manager Jim Riggleman was brought in on April 19. The Reds have gone 40-38 under Riggleman. While Riggleman deserves credit, he also benefitted from the return of Eugenio Suarez and Scott Schebler from the disabled list and Joey Votto rebounding from a slow start. The rotation -- aided by the healthy return of Anthony DeSclafani and the acquisition of Matt Harvey -- has found a groove. Since June 10, the Reds' 21-10 record is best in the National League. While their postseason hopes remain a long shot, there is still plenty of time for the club to feel like it salvaged 2018 and that it built something towards contending in '19.