Spenserian Satire Spenserian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Varieties of Modernist Dystopia

Towson University Office of Graduate Studies BETWEEN THE IDEA AND THE REALITY FALLS THE SHADOW: VARIETIES OF MODERNIST DYSTOPIA by Jonathan R. Moore A thesis Presented to the faculty of Towson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Department of Humanities Towson University Towson, Maryland 21252 May, 2014 Abstract Between the Idea and the Reality Falls the Shadow: Varieties of Modernist Dystopia Jonathan Moore By tracing the literary heritage of dystopia from its inception in Joseph Hall and its modern development under Aldous Huxley, George Orwell, Samuel Beckett, and Anthony Burgess, modern dystopia emerges as a distinct type of utopian literature. The literary environments created by these authors are constructed as intricate social commentaries that ridicule the foolishness of yearning for a leisurely existence in a world of industrial ideals. Modern dystopian narratives approach civilization differently yet predict similarly dismal limitations to autonomy, which focuses attention on the individual and the cultural crisis propagated by shattering conflicts in the modern era. During this era the imaginary nowhere of utopian fables was infected by pessimism and, as the modern era trundled forward, any hope for autonomous individuality contracted. Utopian ideals were invalidated by the oppressive nature of unbridled technology. The resulting societal assessment offers a dark vision of progress. iii Table of Contents Introduction: No Place 1 Chapter 1: Bad Places 19 Chapter 2: Beleaguered Bodies 47 Chapter 3: Cyclical Cacotopias 72 Bibliography 94 Curriculum Vitae 99 iv 1 Introduction: No Place The word dystopia has its origin in ancient Greek, stemming from the root topos which means place. -

County of Emmet

County of Emmet Planning, Zoning & Construction Resources 3434 Harbor-Petoskey Rd Ste E Harbor Springs, Michigan 49740 Phone: 231-348-1735 www.emmetcounty.org Fax: 231-439-8933 EMMET COUNTY BUILDING INSPECTION DEPARTMENT PLAN REVIEW COMPLIANCE LIST 2009 MICHIGAN BUILDING CODE [Date] [Job Number] [Owner's Last Name], [Type of Improvement], [Building Use] [Job Site Address], [Jurisdiction] This work is being reviewed under the provisions of the Michigan Building Code. A copy of the plans submitted and approved by the Emmet County Building Inspection Department will be returned to the applicant and are to remain at the job site during construction. The plans have been reviewed for compliance with Michigan's barrier free design requirements as they may be applicable. This department has no authority over the federal standards contained in the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, 42 U.S.C. 12204. These federal standards may have provisions that apply to your project that should be considered. The building is classified as [identify use group(s)]. The mixed use groups are reviewed as [separated or non-separated] uses. A fire wall with a [identify the hourly rating] rating [indicate the location of the fire wall] is used to create separate buildings. The building height is [identify height(s) in stories and feet]. The building area is [identify the building area(s)]. The permitted open space area increase is [identify the permitted open space area increase(s)]. The sprinkler height increase is [identify the sprinkler height increase]. The permitted sprinkler area increase is [identify the sprinkler area increase]. The minimum type of construction is [identify the type of construction]. -

Proem Shakespeare S 'Plaies and Poems"

Proem Shakespeare s 'Plaies and Poems" In 1640, the publisher John Benson presents to his English reading public a Shakespeare who is now largely lost to us: the national author of poems and plays. By printing his modest octavo edition of the Poems: Written By Wil. Shake-speare. Gent., Benson curiously aims to complement the 1623 printing venture of Shakespeare's theatre colleagues, John Heminge and Henry Condell , who had presented Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies in their monumental First Folio. Thus, in his own Dedicatory Epistle "To the Reader," Benson remarks that he presents "some excellent and sweetly composed Poems," which "had nor the fortune by reason of their lnfancie in his death, to have the due accommodation of proportionable glory, with the rest of his everliving Workes" (*2r). Indeed, as recent scholarship demonstrates, Benson boldly prints his octavo Poems on the model ofHeminge and Condell 's Folio Plays. ' Nor simply does Benson's volume share its primer, Thomas Cores, wirh rhe 1632 Folio, bur both editions begin with an identical format: an engraved portrait of the author; a dedicatory epistle "To the Reader"; and a set of commendatory verses, with Leonard Digges contributing an impor tant celebratory poem to both volumes. Benson's engraving by William Marshall even derives from the famous Martin Droeshout engraving in the First Folio, and six of the eight lines beneath Benson's engraving are borrowed from Ben Jonson's famed memorial poem to Shakespeare in char volume. Accordingly, Benson rakes his publishing goal from Heminge and Conde!!. They aim to "keepe the memory of such worthy a Friend, & Fellow alive" (Dedicatory Epistle to the earls ofPembroke and Montgomery, reprinted in Riverside, 94), while he aims "to be serviceable for the con tinuance of glory to the deserved Author" ("To the Reader," *2v). -

18-Hour Milestone in College English Studies

18-Hour Milestone in College English Studies The Milestone in College English Studies provides a coherent and rigorous course of study for those pursuing a Master of Arts Degree in English who want to teach English core courses at two-year colleges or dual credit English courses in high schools. It helps to ensure quality in the teaching of English core and dual credit courses by enhancing the expertise of English teachers through study of the body of knowledge and theory that builds a solid pedagogical foundation for the organization and delivery of course content. Those who wish to enter a doctoral program with training and teaching experience may also benefit in regard to teaching assistantships. Note: Completion of the Milestone in College English Studies will be designated on a student’s graduate transcript. Admission Eligibility and Progress: Students pursing the Milestone in College English Studies must be concurrently admitted to the Master of Arts program in English or another master’s program at The University of Texas at Tyler. Students must complete a Milestone Permission Form and maintain a cumulative 3.5 GPA for Milestone courses. Curriculum: The Milestone in College English Studies consists of 18-hours (6 courses) all of which count toward the hours needed to complete a Master of Arts in English at UT Tyler. Course emphasis is on composition, literature, and research and theoretical frameworks for teaching College English. Required courses for the Milestone in College English Studies (15 hours): ENGL 5300 Bibliography and -

Rhetoric As Pedagogy

16-Lunsford-45679:Lunsford Sample 7/3/2008 8:17 PM Page 285 PART III Rhetoric and Pedagogy Rhetoric as Pedagogy CHERYL GLENN MARTIN CARCASSON Isocrates was famous in his own day, and for many centuries to come, for his pro - gram of education (paideia), which stressed above all the teaching of eloquence. His own works . were the vehicles for his notion of the true “philosophy,” for him a wisdom in civic affairs emphasizing moral responsibility and equated with mastery of rhetorical technique. —Thomas Conley hetoric has always been a teaching tradition, the pedagogical pursuit of good speaking and Rwriting. When Homer’s (trans. 1938) Achilles, “a rhetor of speech and a doer of deeds,” used language purposefully, persuasively, and eloquently, his voice sparked a rhetorical con - sciousness in the early Greeks ( Iliad 9.443) that was carried into the private sphere by Sappho and then into the public sphere by the Greeks and Romans, who made pedagogy the heart of the rhetorical tradition. To that end, competing theories and practices of rhetoric were displayed and put to the test in the Greek academies of Gorgias, Isocrates, Aspasia, Plato, and Aristotle. Later it flourished as the centerpiece of the Roman educational system made famous by such rhetorical greats as Cicero and Quintilian. More than 2,000 years later, the pedagogy of rhetoric played a key role in the early universities of the United States. During the 18th century, for instance, “rhetoric was treated as the most important subject in the curriculum” (Halloran, 1982). It was not until the 20th century that the importance of rhetoric to the cultivation of citizens both began to wane in the shadow of higher 285 16-Lunsford-45679:Lunsford Sample 7/3/2008 8:17 PM Page 286 286 The SAGE Handbook of Rhetorical Studies education’s shift in focus from the development of rhetorical expertise to that of disciplinary knowledge. -

UNM Physics 262, Problem Set 4, Fall 2006

UNM Physics 262, Problem Set 4, Fall 2006 Instructor: Dr. Landahl Issued: September 13, 2006 Due: September 20, 2006 Do all of the exercises and problems listed below. Hand in your problem set in the rolling cart hand-in box, either before class or after class, or in the box in the Physics and Astronomy main oce by 5 p.m. Please put your box number on your assignment, which is 952 plus your CPS number, as well as the course number (Physics 262). Show all your work, write clearly, indicate directions for all vectors, and be sure to include the units! Credit will be awarded for clear explanations as much, if not more so, than numerical answers. Avoid the temptation to simply write down an equation and move symbols around or plug in numbers. Explain what you are doing, draw pictures, and check your results using common sense, limits, and/or dimensional analysis. Shorter Exercises 4.1. CSI: Albuquerque. As a crime scene investigator, you are sent a strand-like sample that you are told is either a human hair (∼ 25 µm dia.), a dog hair (∼ 30 µm dia.) or a piece of ne carpeting (∼ 40 µm dia.). Remembering the physics you learned about thin wedges, you decide to place the sample (of diameter d) at one end between two square glass (n = 1.52) microscope slides of side length L = 20 cm and shine your trusty crime scene monochromatic sodium lamp of wavelength λ = 590 nm perpendicularly down on the slides. (The setup is similar to Fig. 35.11 in your textbook.) What you see is m = 100 bright fringes going across the slides. -

Spenser, Donne, and the Trouble of Periodization Yulia Ryzhik

Introduction: Spenser, Donne, and the trouble of periodization Yulia Ryzhik The names Edmund Spenser and John Donne are rarely seen together in a scholarly context, and even more rarely seen together as an isolated pairing. When the two are brought together, it is usually for contrast rather than for comparison, and even the comparisons tend to be static rather than dynamic or relational. Spenser and Donne find themselves on two sides of a rift in English Renaissance studies that separates the sixteenth century from the seventeenth and Elizabethan literature from Jacobean.1 In the simplest terms, Spenser is typically associated with the Elizabethan Golden Age, Donne with the ‘metaphysical’ poets of the early seventeenth century. Critical discourse overlooks, or else takes for granted, that Spenser’s and Donne’s poetic careers and chronologies of publication overlapped considerably. Hailed as the Virgil of England, and later as its Homer, Spenser was the reigning ‘Prince of Poets’, and was at the height of his career when Donne began writing in the early 1590s. Both poets, at one point, hoped to secure the patronage of the Earl of Essex, Donne by following him on expeditions to Cadiz and the Azores, Spenser by hailing his victorious return in Prothalamion (1596). The second instalment of Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (also 1596) gives a blistering account in Book V of the European wars of religion in which Ireland, where he lived, was a major conflict zone, but it is Donne who travelled extensively on the Continent, including places where ‘mis-devotion’ reigned.2 Spenser died in 1599 and was buried with much pomp at Westminster Abbey as if poetry itself had died with him. -

Horse-Handling in Shakespeare's Poems And

HORSE-HANDLING IN SHAKESPEARE’S POEMS AND RENAISSANCE CODES OF CONDUCT by Jonathan W. Thurston Master of Arts in English Middle Tennessee State University December 2016 Thesis Committee: Dr. Marion Hollings, Chair Dr. Kevin Donovan, Reader To Temerita, ever faithful. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS After the many hours, days, weeks, and months put into the creation of this thesis, I am proud to express my sincere gratitude to the people who have helped to shape, mold, and inspire the project. First, I owe innumerable thanks to Dr. Marion Hollings. This project started after our first meeting, at which time we discussed the horses of Shakespeare. Gradually, under her tutelage, the thesis was shaped into its current scope and organization. I have occupied her time during many an office hour and one coffee shop day out, discussing the intricacies of early modern equestrianism. She has been a splendid, committed, and passionate director, and I have learned a tremendous amount from her. Second, I would like to thank Dr. Kevin Donovan for his commitment to making the project as sharp and coherent as possible. His suggestions have proven invaluable, and his insight into Shakespearean scholarship has helped to mold this thesis into a well- researched document. Other acknowledgments go out to Dr. Lynn Enterline for teaching me the importance of understanding Italian and Latin for Renaissance texts; the Gay Rodeo Association for free lessons in equestrianism that aided in my embodied phenomenological approach; Sherayah Witcher for helping me through the awkward phrases and the transportation to campus to receive revisions of the drafts; and, finally, Temerita, my muse. -

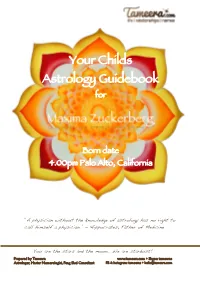

Child Profile for Maxima Zuckerberg

Your Childs Astrology Guidebook for Born date 4.00pm Palo Alto, California “A physician without the knowledge of astrology has no right to call himself a physician.” ~ Hippocrates, Father of Medicine You are the stars and the moon… We are stardust! Prepared by Tameera www.tameera.com s Skype: tameeras Astrologer, Master Numerologist, Feng Shui Consultant FB & Instagram: tameeras s [email protected] 05 K 02 Maxima Zuckerberg L42 12 J 02 i 34 Natal Chart h 30 November 2015 14 07 J L 4:00:00 pm PST 18 k 02 20 A 04 I Palo Alto, California 28L 10 55 g 06 } b 16 A I 54 49 } K J 15 ` L I 27 08 f A I 34 I 07 25 B 25 B H H 03 C G 03 F D E 25 G 10 G 08 c 46 28 d 20 21 F 18 C F 06} G 55 01 j 10 12 e E 23 12D a F 42 34 02 05 E 02 Long. Lat. Decl. R.A. ` 08 ♐ 2713 00 S 00 21 S 43 246 43 a 12 ♌ 23 03 S 38 13 N 36 133 48 b 15 ♐ 54 01 S 34 24 S 15 254 31 c 25 ♎ 08 02 N 09 07 S 43 204 05 Planets by Sign d ♎ N 28 S 55 29 ` 5 Fire 10 46 01 02 190 4 Cardinal 2 Earth e ♍ N 06 N 35 11 a S 1 Fixed 21 01 01 04 172 2 Air b Q S 5 Mutable f 07 ♐ 34 01 N 38 19 S 57 246 04 1 Water c g 16 ♈ 49 ℞ 00 S 39 06 N 00 015 45 d V V h 07 ♓ 04 00 S 48 09 S 40 339 05 e T Prepared by f Q S V Tameera i 14 ♑ 02 01 N 39 21 S 04 285 04 www.tameera.com g S S R l 16 ♓ 57 04 N 28 01 S 02 346 15 h T T m 10 ♑ 36 25 N 47 02 N 42 279 33 i T T n 27 ♎ 03 04 N 31 06 S 13 206 44 l T R V m T V Q o 09 ♒ 07 08 S 39 26 S 17 314 05 n Q p 29 ♓ 39 09 S 01 08 S 25 003 18 o V R S V q 25 ♉ 03 00 N 00 19 N 01 052 42 p r ♒ N 00 S 00 23 ` a b c d e f g h i l m n o p 05 02 00 19 307 You are the stars and -

Elizabethan Sonnet Sequences and the Social Order Author(S): Arthur F

"Love is Not Love": Elizabethan Sonnet Sequences and the Social Order Author(s): Arthur F. Marotti Source: ELH , Summer, 1982, Vol. 49, No. 2 (Summer, 1982), pp. 396-428 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/2872989 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to ELH This content downloaded from 200.130.19.155 on Mon, 27 Jul 2020 13:15:50 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "LOVE IS NOT LOVE": ELIZABETHAN SONNET SEQUENCES AND THE SOCIAL ORDER* BY ARTHUR F. MAROTTI "Every time there is signification there is the possibility of using it in order to lie." -Umberto Ecol It is a well-known fact of literary history that the posthumous publication of Sir Philip Sidney's Astrophil and Stella inaugurated a fashion for sonnet sequences in the last part of Queen Elizabeth's reign, an outpouring of both manuscript-circulated and printed collections that virtually flooded the literary market of the 1590's. But this extraordinary phenomenon was short-lived. With some notable exceptions-such as the delayed publication of Shake- speare's sought-after poems in 1609 and Michael Drayton's con- tinued expansion and beneficial revision of his collection-the composition of sonnet sequences ended with the passing of the Elizabethan era. -

Spenserâ•Žs Epithalamion: a Representation of Colonization

Proceedings of GREAT Day Volume 2014 Article 2 2015 Spenser’s Epithalamion: A Representation of Colonization through Marriage Emily Ercolano SUNY Geneseo Follow this and additional works at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/proceedings-of-great-day Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Ercolano, Emily (2015) "Spenser’s Epithalamion: A Representation of Colonization through Marriage," Proceedings of GREAT Day: Vol. 2014 , Article 2. Available at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/proceedings-of-great-day/vol2014/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the GREAT Day at KnightScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of GREAT Day by an authorized editor of KnightScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ercolano: Spenser’s Epithalamion Spenser’s Epithalamion: A Representation of Colonization through Marriage Emily Ercolano dmund Spenser is believed to have been born mation through sexual intercourse. The speaker, who in London in the year 1552 and to have died is the groom, begins by calling upon the muses and in 1599 in Ireland, where he spent the major- then describes the procession of the bride, the ritual Eity of his career. Unlike the contemporary English rites, the wedding party, the preparation for the wed- poets of his age, Spenser was not born into wealth ding night, and lastly the wedding night with the and nobility, but after receiving an impressive educa- physical consummation of the marriage. The form of tion at the Merchant Taylors’ School, Pembroke Col- the poem parallels the content and firmly places the lege, and Cambridge, he served as an aid and secre- setting in Ireland. -

The History of Florida's State Flag the History of Florida's State Flag Robert M

Nova Law Review Volume 18, Issue 2 1994 Article 11 The History of Florida’s State Flag Robert M. Jarvis∗ ∗ Copyright c 1994 by the authors. Nova Law Review is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nlr Jarvis: The History of Florida's State Flag The History of Florida's State Flag Robert M. Jarvis* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........ .................. 1037 II. EUROPEAN DISCOVERY AND CONQUEST ........... 1038 III. AMERICAN ACQUISITION AND STATEHOOD ......... 1045 IV. THE CIVIL WAR .......................... 1051 V. RECONSTRUCTION AND THE END OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY ..................... 1056 VI. THE TWENTIETH CENTURY ................... 1059 VII. CONCLUSION ............................ 1063 I. INTRODUCTION The Florida Constitution requires the state to have an official flag, and places responsibility for its design on the State Legislature.' Prior to 1900, a number of different flags served as the state's banner. Since 1900, however, the flag has consisted of a white field,2 a red saltire,3 and the * Professor of Law, Nova University. B.A., Northwestern University; J.D., University of Pennsylvania; LL.M., New York University. 1. "The design of the great seal and flag of the state shall be prescribed by law." FLA. CONST. art. If, § 4. Although the constitution mentions only a seal and a flag, the Florida Legislature has designated many other state symbols, including: a state flower (the orange blossom - adopted in 1909); bird (mockingbird - 1927); song ("Old Folks Home" - 1935); tree (sabal palm - 1.953); beverage (orange juice - 1967); shell (horse conch - 1969); gem (moonstone - 1970); marine mammal (manatee - 1975); saltwater mammal (dolphin - 1975); freshwater fish (largemouth bass - 1975); saltwater fish (Atlantic sailfish - 1975); stone (agatized coral - 1979); reptile (alligator - 1987); animal (panther - 1982); soil (Mayakka Fine Sand - 1989); and wildflower (coreopsis - 1991).