Journal of Econometrics Issue of the Annals of Econometrics on Indirect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biometrics & Biostatistics

Hanley and Moodie, J Biomet Biostat 2011, 2:5 Biometrics & Biostatistics http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2155-6180.1000124 Research Article Article OpenOpen Access Access Sample Size, Precision and Power Calculations: A Unified Approach James A Hanley* and Erica EM Moodie Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics, and Occupational Health, McGill University, Canada Abstract The sample size formulae given in elementary biostatistics textbooks deal only with simple situations: estimation of one, or a comparison of at most two, mean(s) or proportion(s). While many specialized textbooks give sample formulae/tables for analyses involving odds and rate ratios, few deal explicitly with statistical considera tions for slopes (regression coefficients), for analyses involving confounding variables or with the fact that most analyses rely on some type of generalized linear model. Thus, the investigator is typically forced to use “black-box” computer programs or tables, or to borrow from tables in the social sciences, where the emphasis is on cor- relation coefficients. The concern in the – usually very separate – modules or stand alone software programs is more with user friendly input and output. The emphasis on numerical exactness is particularly unfortunate, given the rough, prospective, and thus uncertain, nature of the exercise, and that different textbooks and software may give different sample sizes for the same design. In addition, some programs focus on required numbers per group, others on an overall number. We present users with a single universal (though sometimes approximate) formula that explicitly isolates the impacts of the various factors one from another, and gives some insight into the determinants for each factor. -

Biostatistics Student Paper Competition the Department of Biostatistics at BUSPH Is Soliciting Applications for the 2013 Student Paper Competition

Biostatistics Student Paper Competition The Department of Biostatistics at BUSPH is soliciting applications for the 2013 student paper competition. The competition is open to all students enrolled in the Biostatistics Program at Boston University in the spring term of 2013. The winner of the competition will receive $750 as a travel award to attend the summer Joint Statistical Meetings. Travel to other conferences (i.e. ENAR, Society for Clinical Trials, American Society of Human Genetics, International Genetic Epidemiology Society) is possible in negotiation with the award committee. All students are strongly encouraged to submit the abstracts from their papers to the Joint Statistical Meetings, which has a deadline of February 4th. Students would also be encouraged to consider entering the competitions sponsored by sections of the Joint Statistical Meetings (e.g. The Biometrics section Byar Young Investigator award, for details see http://www.bio.ri.ccf.org/Biometrics/winner.html). TIMETABLE: January 11th, 2013 at noon: Deadline for students to submit pdf of manuscript January 25th, 2013: Announcement of awards REQUIREMENTS: The paper should be prepared double spaced, in manuscript format, using guidelines for authors typical of a biostatistical journal (e.g. Biometrics, Statistics in Medicine, or Biostatistics). A pdf copy of the manuscript should be submitted to the chair of the award committee, Ching-Ti Liu ([email protected]). The reported work should be relevant to biostatistics and must be the work of the student, although the manuscript can be co-authored with a faculty advisor or a small number of collaborators. The student must be the first author of the manuscript. -

Biometrical Applications in Biological Sciences-A Review on the Agony for Their Practical Efficiency- Problems and Perspectives

Biometrics & Biostatistics International Journal Review Article Open Access Biometrical applications in biological sciences-A review on the agony for their practical efficiency- Problems and perspectives Abstract Volume 7 Issue 5 - 2018 The effect of the three biological sciences- agriculture, environment and medicine S Tzortzios in the people’s life is of the greatest importance. The chain of the influence of the University of Thessaly, Greece environment to the form and quality of the agricultural production and the effect of both of them to the people’s health and welfare consists in an integrated system Correspondence: S Tzortzios, University of Thessaly, Greece, that is the basic substance of the human life. Agriculture has a great importance in Email [email protected] the World’s economy; however, the available resources for research and technology development are limited. Moreover, the environmental and productive conditions are Received: August 12, 2018 | Published: October 05, 2018 very different from one country to another, restricting the generalized transferring of technology. The statistical methods should play a paramount role to insure both the objectivity of the results of agricultural research as well as the optimum usage of the limited resources. An inadequate or improper use of statistical methods may result in wrong conclusions and in misuse of the available resources with important scientific and economic consequences. Many times, Statistics is used as a basis to justify conclusions of research work without considering in advance the suitability of the statistical methods to be used. The obvious question is: What importance do biological researchers give to the statistical methods? The answer is out of any doubt and the fact that most of the results published in specialized journals includes statistical considerations, confirms its importance. -

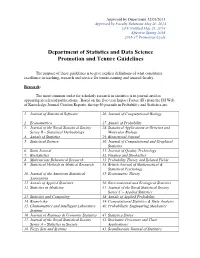

Department of Statistics and Data Science Promotion and Tenure Guidelines

Approved by Department 12/05/2013 Approved by Faculty Relations May 20, 2014 UFF Notified May 21, 2014 Effective Spring 2016 2016-17 Promotion Cycle Department of Statistics and Data Science Promotion and Tenure Guidelines The purpose of these guidelines is to give explicit definitions of what constitutes excellence in teaching, research and service for tenure-earning and tenured faculty. Research: The most common outlet for scholarly research in statistics is in journal articles appearing in refereed publications. Based on the five-year Impact Factor (IF) from the ISI Web of Knowledge Journal Citation Reports, the top 50 journals in Probability and Statistics are: 1. Journal of Statistical Software 26. Journal of Computational Biology 2. Econometrica 27. Annals of Probability 3. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 28. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Series B – Statistical Methodology Molecular Biology 4. Annals of Statistics 29. Biometrical Journal 5. Statistical Science 30. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics 6. Stata Journal 31. Journal of Quality Technology 7. Biostatistics 32. Finance and Stochastics 8. Multivariate Behavioral Research 33. Probability Theory and Related Fields 9. Statistical Methods in Medical Research 34. British Journal of Mathematical & Statistical Psychology 10. Journal of the American Statistical 35. Econometric Theory Association 11. Annals of Applied Statistics 36. Environmental and Ecological Statistics 12. Statistics in Medicine 37. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series C – Applied Statistics 13. Statistics and Computing 38. Annals of Applied Probability 14. Biometrika 39. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 15. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory 40. Probabilistic Engineering Mechanics Systems 16. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 41. -

Curriculum Vitae

Daniele Durante: Curriculum Vitae Contact Department of Decision Sciences B: [email protected] Information Bocconi University web: https://danieledurante.github.io/web/ Via R¨ontgen, 1, 20136 Milan Research Network Science, Computational Social Science, Latent Variables Models, Complex Data, Bayesian Interests Methods & Computation, Demography, Statistical Learning in High Dimension, Categorical Data Current Assistant Professor Academic Bocconi University, Department of Decision Sciences 09/2017 | Present Positions Research Affiliate • Bocconi Institute for Data Science and Analytics [bidsa] • Dondena Centre for Research on Social Dynamics and Public Policy • Laboratory for Coronavirus Crisis Research [covid crisis lab] Past Post{Doctoral Research Fellow 02/2016 | 08/2017 Academic University of Padova, Department of Statistical Sciences Positions Adjunct Professor 12/2015 | 12/2016 Ca' Foscari University, Department of Economics and Management Visiting Research Scholar 03/2014 | 02/2015 Duke University, Department of Statistical Sciences Education University of Padova, Department of Statistical Sciences Ph.D. in Statistics. Department of Statistical Sciences 2013 | 2016 • Ph.D. Thesis Topic: Bayesian nonparametric modeling of network data • Advisor: Bruno Scarpa. Co-advisor: David B. Dunson M.Sc. in Statistical Sciences. Department of Statistical Sciences 2010 | 2012 B.Sc. in Statistics, Economics and Finance. Department of Statistics 2007 | 2010 Awards Early{Career Scholar Award for Contributions to Statistics. Italian Statistical Society 2021 Bocconi Research Excellence Award. Bocconi University 2021 Leonardo da Vinci Medal. Italian Ministry of University and Research 2020 Bocconi Research Excellence Award. Bocconi University 2020 Bocconi Innovation in Teaching Award. Bocconi University 2020 National Scientific Qualification for Associate Professor in Statistics [13/D1] 2018 Doctoral Thesis Award in Statistics. -

Area13 ‐ Riviste Di Classe A

Area13 ‐ Riviste di classe A SETTORE CONCORSUALE / TITOLO 13/A1‐A2‐A3‐A4‐A5 ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT ANNALS ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT JOURNAL ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT LEARNING & EDUCATION ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVES ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT REVIEW ACCOUNTING REVIEW ACCOUNTING, AUDITING & ACCOUNTABILITY JOURNAL ACCOUNTING, ORGANIZATIONS AND SOCIETY ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY ADVANCES IN APPLIED PROBABILITY AGEING AND SOCIETY AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL. APPLIED ECONOMICS AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL. ECONOMIC POLICY AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL: MACROECONOMICS AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL: MICROECONOMICS AMERICAN JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW AMERICAN REVIEW OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION ANNALES DE L'INSTITUT HENRI POINCARE‐PROBABILITES ET STATISTIQUES ANNALS OF PROBABILITY ANNALS OF STATISTICS ANNALS OF TOURISM RESEARCH ANNU. REV. FINANC. ECON. APPLIED FINANCIAL ECONOMICS APPLIED PSYCHOLOGICAL MEASUREMENT ASIA PACIFIC JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT AUDITING BAYESIAN ANALYSIS BERNOULLI BIOMETRICS BIOMETRIKA BIOSTATISTICS BRITISH JOURNAL OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS BRITISH JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT BRITISH JOURNAL OF MATHEMATICAL & STATISTICAL PSYCHOLOGY BROOKINGS PAPERS ON ECONOMIC ACTIVITY BUSINESS ETHICS QUARTERLY BUSINESS HISTORY REVIEW BUSINESS HORIZONS BUSINESS PROCESS MANAGEMENT JOURNAL BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW CAMBRIDGE JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS CANADIAN JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS CANADIAN JOURNAL OF FOREST RESEARCH CANADIAN JOURNAL OF STATISTICS‐REVUE CANADIENNE DE STATISTIQUE CHAOS CHAOS, SOLITONS -

Rank Full Journal Title Journal Impact Factor 1 Journal of Statistical

Journal Data Filtered By: Selected JCR Year: 2019 Selected Editions: SCIE Selected Categories: 'STATISTICS & PROBABILITY' Selected Category Scheme: WoS Rank Full Journal Title Journal Impact Eigenfactor Total Cites Factor Score Journal of Statistical Software 1 25,372 13.642 0.053040 Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 2 515 5.095 0.004250 ECONOMETRICA 3 35,846 3.992 0.040750 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN STATISTICAL ASSOCIATION 4 36,843 3.989 0.032370 JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL STATISTICAL SOCIETY SERIES B-STATISTICAL METHODOLOGY 5 25,492 3.965 0.018040 STATISTICAL SCIENCE 6 6,545 3.583 0.007500 R Journal 7 1,811 3.312 0.007320 FUZZY SETS AND SYSTEMS 8 17,605 3.305 0.008740 BIOSTATISTICS 9 4,048 3.098 0.006780 STATISTICS AND COMPUTING 10 4,519 3.035 0.011050 IEEE-ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics 11 3,542 3.015 0.006930 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS & ECONOMIC STATISTICS 12 5,921 2.935 0.008680 CHEMOMETRICS AND INTELLIGENT LABORATORY SYSTEMS 13 9,421 2.895 0.007790 MULTIVARIATE BEHAVIORAL RESEARCH 14 7,112 2.750 0.007880 INTERNATIONAL STATISTICAL REVIEW 15 1,807 2.740 0.002560 Bayesian Analysis 16 2,000 2.696 0.006600 ANNALS OF STATISTICS 17 21,466 2.650 0.027080 PROBABILISTIC ENGINEERING MECHANICS 18 2,689 2.411 0.002430 BRITISH JOURNAL OF MATHEMATICAL & STATISTICAL PSYCHOLOGY 19 1,965 2.388 0.003480 ANNALS OF PROBABILITY 20 5,892 2.377 0.017230 STOCHASTIC ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH AND RISK ASSESSMENT 21 4,272 2.351 0.006810 JOURNAL OF COMPUTATIONAL AND GRAPHICAL STATISTICS 22 4,369 2.319 0.008900 STATISTICAL METHODS IN -

Econometrics of Sampled Networks

ECONOMETRICS OF SAMPLED NETWORKS ARUN G. CHANDRASEKHAR‡ AND RANDALL LEWIS§ Abstract. A growing literature studies social networks and their implications for economic outcomes. This paper highlights, examines, and addresses econometric problems that arise when a researcher studies network effects using sampled network data. In applied work, researchers generally construct networks from data collected from a partial sample of nodes. For example, in a village, a researcher asks a random subset of households to report their social contacts. Treating this sampled network as the true network of interest, the researcher constructs statistics to describe the network or specific nodes and employs these statistics in regression or generalized method-of-moments (GMM) analysis. This paper shows that even if nodes are selected randomly, partial sampling leads to non-classical measurement error and therefore bias in estimates of the regression coefficients or GMM parameters. The paper presents the first in-depth look at the impact of missing network data on the estimation of economic parameters. We provide analytic and numeric examples to illustrate the severity of the biases in common applications. We then develop two new strategies to correct such biases: a set of analytic corrections for commonly used network statistics and a two-step estimation procedure using graphical reconstruction. Graphical reconstruction uses the available (partial) network data to predict what the full network would have been and uses these predictions to mitigate the biases. We derive asymptotic theory that allows for each network in the data set to be generated by a different network formation model. Our analysis of the sampling problem as well as the proposed solutions are applied to rich network data of Banerjee, Chandrasekhar, Duflo, and Jackson(2013) from 75 villages in Karnataka, India. -

Journal of Econometrics Efficient Semiparametric Estimation of Multi

Journal of Econometrics 155 (2010) 138–154 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Econometrics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jeconom Efficient semiparametric estimation of multi-valued treatment effects under ignorabilityI Matias D. Cattaneo ∗ Department of Economics, University of Michigan, United States article info a b s t r a c t Article history: This paper studies the efficient estimation of a large class of multi-valued treatment effects as implicitly Received 22 January 2009 defined by a collection of possibly over-identified non-smooth moment conditions when the treatment Received in revised form assignment is assumed to bep ignorable. Two estimators are introduced together with a set of sufficient 12 July 2009 conditions that ensure their n-consistency, asymptotic normality and efficiency. Under mild assump- Accepted 22 September 2009 tions, these conditions are satisfied for the Marginal Mean Treatment Effect and the Marginal Quantile Treat- Available online 7 October 2009 ment Effect, estimands of particular importance for empirical applications. Previous results for average and quantile treatments effects are encompassed by the methods proposed here when the treatment is JEL classification: C14 dichotomous. The results are illustrated by an empirical application studying the effect of maternal smok- C21 ing intensity during pregnancy on birth weight, and a Monte Carlo experiment. C31 ' 2009 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Multi-valued treatment effects Unconfoundedness Semiparametric efficiency Efficient estimation 1. Introduction status into a binary indicator for eligibility or participation, a pro- cedure that allows for the application of available semiparamet- A large fraction of the literature on program evaluation fo- ric econometric techniques at the expense of a considerable loss cuses on efficient, flexible estimation of treatment effects under of information. -

Journal of the Royal Statistical Society

Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Notes on the Submission of Papers Disclosure of financial and other interests Some journals have policies requiring authors of submitted papers to declare potential conflicts of interest. The purpose is not to remove the conflict but to publicize it, and to allow readers to form their own conclusions on whether any conflict of interest exists. For many of the papers submitted to the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society this is unlikely to be an issue. However, such interests may take many forms, including financial considerations and situations where one or more of the authors have acted as consultants or advisors (paid or otherwise) to a project relevant to the submitted paper. This does not imply that there is anything wrong with holding such interests or that research published by authors with such interests is thereby compromised. With the aim of encouraging transparency and accountability, however, authors of material submitted to the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society are asked to disclose any financial or other interest that may be relevant and/or would prove an embarrassment if it were to emerge after publication and they had not declared it. The appropriate place for such disclosures is in a covering note to the Editor. At the Editor's discretion, this information may be printed at the end of the paper if it is published. Data sets and computer code It is the policy of the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society that published papers should, where possible, be accompanied by the data and computer code used in the analysis. -

Computational Statistics (Journal)1 CSF0019 Wolfgang Karl Hardle¨ Correspondence To: [email protected] C.A.S.E

Computational Statistics Forschungsgemeinschaft through through Forschungsgemeinschaft SFB 649DiscussionPaper2012-004 Wolfgang KarlHärdle* This research was supported by the Deutsche the Deutsche by was supported This research Jürgen Symanzik*** * Humboldt-UniversitätzuBerlin,Germany SFB 649, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin zu SFB 649,Humboldt-Universität ** Okayama University ofScience,Japan ** Okayama Spandauer Straße 1,D-10178 Berlin Spandauer http://sfb649.wiwi.hu-berlin.de http://sfb649.wiwi.hu-berlin.de *** Utah State University, USA *** UtahStateUniversity,USA Yuichi Mori** (Journal) ISSN 1860-5664 the SFB 649 "Economic Risk". "Economic the SFB649 SFB 6 4 9 E C O N O M I C R I S K B E R L I N Article type: Focus Article Computational Statistics (Journal)1 CSF0019 Wolfgang Karl Hardle¨ Correspondence to: [email protected] C.A.S.E. Centre for Applied Statistics and Economics, School of Business and Economics, Humboldt–Universitat¨ zu Berlin, Unter den Linden 6, 10099 Berlin, Germany Yuichi Mori Correspondence to: [email protected] Dept. of Socio–Information, Faculty of Informatics, Okayama University of Sci- ence, 1–1 Ridai–cho, Kita–ku, Okayama 700–0005, Japan J¨urgen Symanzik Correspondence to: [email protected] Utah State University, Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Logan, UT 84322–3900, USA Abstract Computational Statistics is an international journal that fosters the publication of applications and methodological research in the field of computational statis- tics. In this article, we will discuss the motivation, history, some specialties, and the future scope of this journal. Keywords: International journal, history of the journal, specialties of the journal, online communications JEL classification: C63, C88, Y30 INTRODUCTION The focus of papers in the Springer–published journal Computational Statistics (Com- put Stat2), accessible at http://www.springer.com/statistics/journal/180, is on the contribution to and influence of computing on statistics and vice versa. -

Econometric Methods for Program Evaluation

EC10CH18_Abadie ARI 28 June 2018 11:30 Annual Review of Economics Econometric Methods for Program Evaluation Alberto Abadie1 and Matias D. Cattaneo2 1Department of Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142, USA; email: [email protected] 2Department of Economics and Department of Statistics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, USA; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Econ. 2018.10:465-503. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Annu. Rev. Econ. 2018. 10:465–503 Keywords Access provided by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) on 03/19/19. For personal use only. The Annual Review of Economics is online at causal inference, policy evaluation, treatment effects economics.annualreviews.org https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics- Abstract 080217-053402 Program evaluation methods are widely applied in economics to assess the Copyright c 2018 by Annual Reviews. effects of policy interventions and other treatments of interest. In this article, All rights reserved we describe the main methodological frameworks of the econometrics of JEL codes: C1, C2, C3, C54 program evaluation. In the process, we delineate some of the directions along which this literature is expanding, discuss recent developments, and highlight specific areas where new research may be particularly fruitful. 465 EC10CH18_Abadie ARI 28 June 2018 11:30 1. INTRODUCTION The nature of empirical research in economics has profoundly changed since the emergence in the 1990s of a new way to understand identification in econometric models. This approach emphasizes the importance of heterogeneity across units in the parameters of interest and of the choice of the sources of variation in the data that are used to estimate those parameters.