The Weird and the Eerie (Beyond the Unheimlich)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick De Don

UNIVERSIDAD DE OVIEDO FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS MEMORIA DE LICENCIATURA From Don Quixote to The Tick: The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick ____________ De Don Quijote a The Tick: El Reflejo de Sancho Panza en el sidekick del Cómic Autor: José Manuel Annacondia López Directora: Dra. María José Álvarez Faedo VºBº: Oviedo, 2012 To comic book creators of yesterday, today and tomorrow. The comics medium is a very specialized area of the Arts, home to many rare and talented blooms and flowering imaginations and it breaks my heart to see so many of our best and brightest bowing down to the same market pressures which drive lowest-common-denominator blockbuster movies and television cop shows. Let's see if we can call time on this trend by demanding and creating big, wild comics which stretch our imaginations. Let's make living breathing, sprawling adventures filled with mind-blowing images of things unseen on Earth. Let's make artefacts that are not faux-games or movies but something other, something so rare and strange it might as well be a window into another universe because that's what it is. [Grant Morrison, “Grant Morrison: Master & Commander” (2004: 2)] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements v 2. Introduction 1 3. Chapter I: Theoretical Background 6 4. Chapter II: The Nature of Comic Books 11 5. Chapter III: Heroes Defined 18 6. Chapter IV: Enter the Sidekick 30 7. Chapter V: Dark Knights of Sad Countenances 35 8. Chapter VI: Under Scrutiny 53 9. Chapter VII: Evolve or Die 67 10. -

Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction

Andrew May Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction Editorial Board Mark Alpert Philip Ball Gregory Benford Michael Brotherton Victor Callaghan Amnon H Eden Nick Kanas Geoffrey Landis Rudi Rucker Dirk Schulze-Makuch Ru€diger Vaas Ulrich Walter Stephen Webb Science and Fiction – A Springer Series This collection of entertaining and thought-provoking books will appeal equally to science buffs, scientists and science-fiction fans. It was born out of the recognition that scientific discovery and the creation of plausible fictional scenarios are often two sides of the same coin. Each relies on an understanding of the way the world works, coupled with the imaginative ability to invent new or alternative explanations—and even other worlds. Authored by practicing scientists as well as writers of hard science fiction, these books explore and exploit the borderlands between accepted science and its fictional counterpart. Uncovering mutual influences, promoting fruitful interaction, narrating and analyzing fictional scenarios, together they serve as a reaction vessel for inspired new ideas in science, technology, and beyond. Whether fiction, fact, or forever undecidable: the Springer Series “Science and Fiction” intends to go where no one has gone before! Its largely non-technical books take several different approaches. Journey with their authors as they • Indulge in science speculation—describing intriguing, plausible yet unproven ideas; • Exploit science fiction for educational purposes and as a means of promoting critical thinking; • Explore the interplay of science and science fiction—throughout the history of the genre and looking ahead; • Delve into related topics including, but not limited to: science as a creative process, the limits of science, interplay of literature and knowledge; • Tell fictional short stories built around well-defined scientific ideas, with a supplement summarizing the science underlying the plot. -

Captain Marvel

Roy Thomas’On-The-Marc Comics Fanzine AND $8.95 In the USA No.119 August 2013 A 100th Birthday Tribute to MARC SWAYZE PLUS: SHELDON MOLDOFF OTTO BINDER C.C. BECK JUNE SWAYZE and all the usual SHAZAM! SUSPECTS! 7 0 5 3 6 [Art ©2013 DC7 Comics Inc.] 7 BONUS FEATURE! 2 8 THE MANY COMIC ART 5 6 WORLDS OF 2 TM & © DC Comics. 8 MEL KEEFER 1 Vol. 3, No. 119 / August 2013 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White Mike Friedrich Proofreaders Rob Smentek William J. Dowlding Cover Artists Marc Swayze Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko Writer/Editorial: Marc Of A Gentleman . 2 With Special Thanks to: The Multi-Talented Mel Keefer . 3 Heidi Amash Aron Laikin Alberto Becattini queries the artist about 40 years in comics, illustration, animation, & film. Terrance Armstard Mark Lewis Mr.Monster’sComicCrypt!TheMenWhoWouldBeKurtzman! 29 Richard J. Arndt Alan Light Mark Arnold Richard Lupoff Michael T. Gilbert showcases the influence of the legendary Harvey K. on other great talents. Paul Bach Giancarlo Malagutti Comic Fandom Archive: Spotlight On Bill Schelly . 35 Bob Bailey Brian K. Morris Alberto Becattini Kevin Patrick Gary Brown throws a 2011 San Diego Comic-Con spotlight on A/E’s associate editor. Judy Swayze Barry Pearl re: [correspondence, comments, & corrections] . 43 Blackman Grey Ray Gary Brown Warren Reece Tributes to Fran Matera, Paul Laikin, & Monty Wedd . -

The Comic Book and the Korean War

ADVANCINGIN ANOTHERDIRECTION The Comic Book and the Korean War "JUNE,1950! THE INCENDIARY SPARK OF WAR IS- GLOWING IN KOREA! AGAIN AS BEFORE, MEN ARE HUNTING MEN.. .BIAXlNG EACH OTHER TO BITS . COMMITTING WHOLESALE MURDER! THIS, THEN, IS A STORY OF MAN'S INHUMANITY TO MAN! THIS IS A WAR STORY!" th the January-February 1951 issue of E-C Comic's Two- wFisted Tales, the comic book, as it had for WWII five years earlier, followed the United States into the war in Korea. Soon other comic book lines joined E-C in presenting aspects of the new war in Korea. Comic books remain an underutilized popular culture resource in the study of war and yet they provide a very rich part of the tapestry of war and cultural representation. The Korean War comics are also important for their location in the history of the comic book industry. After WWII, the comic industry expanded rapidly, and by the late 1940s comic books entered a boom period with more adults reading comics than ever before. The period between 1935 and 1955 has been characterized as the "Golden Age" of the comic book with over 650 comic book titles appearing monthly during the peak years of popularity in 1953 and 1954 (Nye 239-40). By the late forties, many comics directed the focus away from a primary audience of juveniles and young adolescents to address volatile adult issues in the postwar years, including juvenile delinquency, changing family dynamics, and human sexuality. The emphasis shifted during this period from super heroes like "Superman" to so-called realistic comics that included a great deal of gore, violence, and more "adult" situations. -

ASTONISHING SWORDSMEN and SORCERERS of Hype Rborea TM

ASTONISHING SWORDSMEN AND SORCERERS OF hype RBOrEa TM Sample file A Role-Playing Game of Swords, Sorcery, and Weird Fantasy Sample file Sample file ASTONISHING SWORDSMEN & SORCERERS OF HYPERBOREA ASTONISHING SWORDSMEN & SORCERERS OF HYPERBOREA™ A Role-Playing Game of Swords, Sorcery, and Weird Fantasy A COMPLEAT REFERENCE BOOK PRESENTED IN SIX VOLUMES Sample file www.HYPERBOREA.tv iv A ROLE-PLAYING GAME OF SWORDS, SORCERY, AND WEIRD FANTASY CREDITS Text: Jeffrey P. Talanian Editing: David Prata Cover Art: Charles Lang Frontispiece Art: Val Semeiks Frontispiece Colours: Daisey Bingham Interior Art: Ian Baggley, Johnathan Bingham, Charles Lang, Peter Mullen, Russ Nicholson, Glynn Seal, Val Semeiks, Jason Sholtis, Logan Talanian, Del Teigeler Cartography: Glynn Seal Graphic Embellishments: Glynn Seal Layout: Jeffrey P. Talanian Play-Testing (Original Edition): Jarrett Beeley, Dan Berube, Jonas Carlson, Jim Goodwin, Don Manning, Ethan Oyer Play-Testing (Second Edition): Dan Berube, Dennis Bretton, John Cammarata, Jonas Carlson, Don Manning, Anthony Merida, Charles Merida, Mark Merida Additional Development (Original Edition): Ian Baggley, Antonio Eleuteri, Morgan Hazel, Joe Maccarrone, Benoist Poiré, David Prata, Matthew J. Stanham Additional Development (Second Edition): Ben Ball, Chainsaw, Colin Chapman, Rich Franks, Michael Haskell, David Prata, Joseph Salvador With Forewords by Chris Gruber and Stuart Marshall ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The milieux of Astonishing Swordsmen & Sorcerers of Hyperborea™ are inspired by the fantastic literature of Robert E. Howard, H.P. Lovecraft, and Clark Ashton Smith. Other inspirational authors include Edgar Rice Burroughs, Fritz Leiber, Abraham Merritt, Michael Moorcock, Jack Vance, and Karl Edward Wagner. AS&SH™ rules and conventions are informed by the original 1974 fantasy wargame and miniatures campaign rules as conceived by E. -

Lotfp Weird Fantasy Role-Playing Has, Since Its Last Printing, Taken a Decidedly Early Modern Focus in Its Supplements and Adventures

LamentationS of the Flame PrincesS Weird Fantasy Role-Playing 1 LamentationS Mystery and Imagination of the Flame PrincesS Adventure and Death Weird Fantasy Role-Playing LamentationS of the Flame PrincesS Weird Fantasy Role-Playing Beyond the veil of reality, beyond the inuence of manipulating politicians, greedy merchants, iron-handed clergy, and the broken masses that toil for Rules their benet, echoes of other realms call to those bold enough, and desperate enough, to escape the oppression of mundane life. Treasure and glory await those courageous enough to wrest it from the darkness. But the danger is great, for lurking in the forgoen shadows are forces far stranger and more perilous than even civilization. e price of freedom might be paid in souls. Magic LotFP: Weird Fantasy Role-Playing presents a sinister and horric twist on traditional fantasy gaming. Simple enough for a beginner yet meaty enough for the veteran, this game will make all your worst nightmares come true. is book is a revision of the Rules & Magic book originally found in the LotFP: Weird Fantasy Role-Playing boxed set. It contains all the rules needed to play the game. is is the rst book of a two book set. e Referee Core Book: Procedures and Inspirations contains information and guidance about constructing and running campaigns and adventures. LamentationS of the Flame PrincesS Weird Fantasy Role-Playing F F F Wei Wei Wei Lam Lam Lam © James Edward Raggi IV la la la rd F rd F rd F me PrincesS me PrincesS me PrincesS me ant ant ant LamentationS en en en a a a of -

The City & the City by China Miéville in the Context of the Genre “New Weird”

Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Filozofická fakulta Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Eliška Fialová The City & The City by China Miéville in the context of the genre “New Weird” Vedoucí práce: Prof. PhDr. Michal Peprník, Dr. Olomouc 2016 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatn ě a p ředepsaným zp ůsobem v ní uvedla všechnu použitou literaturu. V Olomouci dne 25. dubna 2016 Eliška Fialová Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor prof. PhDr. Michal Peprník Dr. for all his help and valuable advice during the process of writing this thesis. Also, I would like to thank Dr Jeannette Baxter from Anglia Ruskin University for her inspiring guest seminar The Haunted Contemporary which introduced me to the genre of New Weird. Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 Literary context for fantasy writer China Miéville ......................................... 2 Victorian fantasy ................................................................................................ 7 Gothic romances ............................................................................................... 11 Tolkien and the EFP and China Miéville ......................................................... 15 Weird fiction ...................................................................................................... 20 Characteristics of weird fiction ........................................................................ 20 Pre-weird -

Heret, by Illustrator and Comics Creator Dan Mucha and Toulouse Letrec Were in Brereton

Featured New Items FAMOUS AMERICAN ILLUSTRATORS On our Cover Specially Priced SOI file copies from 1997! Our NAUGHTY AND NICE The Good Girl Art of Highest Recommendation. By Bruce Timm Publisher Edition Arpi Ermoyan. Fascinating insights New Edition. Special into the lives and works of 82 top exclusive Publisher’s artists elected to the Society of Hardcover edition, 1500. Illustrators Hall of Fame make Highly Recommended. this an inspiring reference and art An extensive survey of book. From illustrators such as N.C. Bruce Timm’s celebrated Wyeth to Charles Dana Gibson to “after hours” private works. Dean Cornwell, Al Parker, Austin These tastefully drawn Briggs, Jon Whitcomb, Parrish, nudes, completed purely for Pyle, Dunn, Peak, Whitmore, Ley- fun, are showcased in this endecker, Abbey, Flagg, Gruger, exquisite new release. This Raleigh, Booth, LaGatta, Frost, volume boasts over 250 Kent, Sundblom, Erté, Held, full-color or line and pencil Jessie Willcox Smith, Georgi, images, each one full page. McGinnis, Harry Anderson, Bar- It’s all about sexy, nubile clay, Coll, Schoonover, McCay... girls: partially clothed or fully nude, of almost every con- the list of greats goes on and on. ceivable description and temperament. Girls-next-door, Society of Illustrators, 1997. seductresses, vampires, girls with guns, teases...Timm FAMAMH. HC, 12x12, 224pg, FC blends his animation style with his passion for traditional $40.00 $29.95 good-girl art for an approach that is unmistakably all his JOHN HASSALL own. Flesk, 2021. Mature readers. NOTE: Unlike the The Life and Art of the Poster King first, Timm didn’t sign this second printing. -

President's Column the Nebulas Have a Cold Confluence Parsec Picnic Tarzan Meets Superman! More Tarzan! Brief Bios Bernard

President’s Column The Nebulas Have a Cold Confluence Parsec Picnic Tarzan Meets Superman! More Tarzan! Brief Bios Bernard Herrmann Part 2 A Newbie At The Nebbies. Parsec Meeting Schedule President’s Column and so help me The Crypt of Terror and The Vault of Horror. Spa Fon! I was time-slipped to the front porch of my childhood Carver Street home, a stack of luscious comic books piled high, my behind on gray painted concrete, sneakers on the stoop, a hot humid day. (Yes, my mother absolutely threw a fortune away.) As I and my doppelgänger read and viewed, I knew that this encounter with comic books was the missing dimension for which I had been yearning. I continue to read and am mighty partial, not to the superhero books, but to the graphic editions that draw from and create true science fiction. Mystery In Space, Weird Science, Weird Fantasy, Journey Into the Unknown, Planet Comics, Tales of Suspense, Out of this World, Unknown Worlds, the Buck Rogers.Flash Gordon and Brick Bradford newspaper comic strips, even in the name of all that has crumbled, Magnus Robot Fighter. The incomplete list does not even begin to contemplate any modern comic book attempts at SF. People ask me, “How do you find time to read?”As if that was a legitimate question. I answer, “How is it that you can’t find the time? Are you standing in a supermarket line, eating breakfast, waiting for the movie to begin, riding on the bus, sitting in your backyard, taking the dog for a stroll, mowing the lawn?” I do get a few peculiar looks while intent on the EC work of Wally Wood, Johnie Craig and Al Feldstein as I peddle the hamster running machine at the gym. -

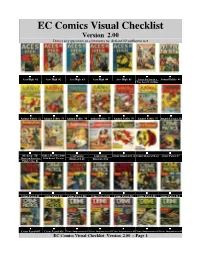

EC Comics Visual Checklist Version 2.00 Direct Any Question Or Comments To: [email protected]

EC Comics Visual Checklist Version 2.00 Direct any question or comments to: [email protected] Aces High #1 Aces High #2 Aces High #3 Aces High #4 Aces High #5 Across the Seas in a Animal Fables #1 War Torn World #nn Animal Fables #2 Animal Fables #3 Animal Fables #4 Animal Fables #5 Animal Fables #6 Animal Fables #7 Animated Comics #1 Blackstone, The Church That Was Bu ilt Confessions Confessions Crime Illustrated #1 Crime Illustrated #2 Crime Patrol #7 Magician Detective With Bread, The #nn Illustrated #1 Illustrated #2 Fights Crime #1 Crime Patrol #8 Crime Patrol #9 Crime Patrol #10 Crime Patrol #11 Crime Patrol #12 Crime Patrol #13 Crime Patrol #14 Crime Patrol #15 Crime Patrol #16 Crime Suspenstories #1 Crime Suspenstories #2 Crime Suspenstories #3 Crime Suspenstories #4 Crime Suspenstories #5 EC Comics Visual Checklist Version 2.00 – Page 1 EC Comics Visual Checklist Version 2.00 – Page 2 Crime Crime Crime Crime Crime Crime Crime Suspenstories #6 Suspenstories #7 Suspenstories #8 Suspenstories #9 Suspenstories #10 Suspenstories #11 Suspenstories #12 Crime Crime Crime Crime Crime Crime Crime Suspenstories #13 Suspenstories #14 Suspenstories #15 Suspenstories #16 Suspenstories #17 Suspenstories #18 Suspenstories #19 Crime Crime Crime Crime Crime Crime Crime Suspenstories #20 Suspenstories #21 Suspenstories #22 Suspenstories #23 Suspenstories #24 Suspenstories #25 Suspenstories #26 Crime Crypt of Crypt of Crypt of Dandy Comics #1 Dandy Comics #2 Dandy Comics #3 Suspenstories #27 Terror #14 Terror #15 Terror #16 Dandy Comics #4 Dandy -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items FAMOUS AMERICAN ILLUSTRATORS On our Cover Specially Priced SOI file copies from 1997! Our NAUGHTY AND NICE The Good Girl Art of Highest Recommendation. By Bruce Timm Publisher Edition Arpi Ermoyan. Fascinating insights New Edition. Special into the lives and works of 82 top exclusive Publisher’s artists elected to the Society of Hardcover edition, 1500. Illustrators Hall of Fame make Highly Recommended. this an inspiring reference and art An extensive survey of book. From illustrators such as N.C. Bruce Timm’s celebrated Wyeth to Charles Dana Gibson to “after hours” private works. Dean Cornwell, Al Parker, Austin These tastefully drawn Briggs, Jon Whitcomb, Parrish, nudes, completed purely for Pyle, Dunn, Peak, Whitmore, Ley- fun, are showcased in this endecker, Abbey, Flagg, Gruger, exquisite new release. This Raleigh, Booth, LaGatta, Frost, volume boasts over 250 Kent, Sundblom, Erté, Held, full-color or line and pencil Jessie Willcox Smith, Georgi, images, each one full page. McGinnis, Harry Anderson, Bar- It’s all about sexy, nubile clay, Coll, Schoonover, McCay... girls: partially clothed or fully nude, of almost every con- the list of greats goes on and on. ceivable description and temperament. Girls-next-door, Society of Illustrators, 1997. seductresses, vampires, girls with guns, teases...Timm FAMAMH. HC, 12x12, 224pg, FC blends his animation style with his passion for traditional $40.00 $29.95 good-girl art for an approach that is unmistakably all his JOHN HASSALL own. Flesk, 2021. Mature readers. NOTE: Unlike the The Life and Art of the Poster King first, Timm didn’t sign this second printing. -

Fantasy Review Would Long Since Have Given up the Struggle

FA NI TASY REV It VV Vol. III. No. 15 ONE SHILLING SUMMER'49 EXTENSION In discussing the disproportionate production costs which hamper any publishing venture catering for a limited circle of readers, Mr. August Derleth, editor and publisher of The Arkham Sampler, announces the imminent suspension oI that valuable periodical. Which prompts us to point out that, had it been launched as a proflt-making proposition, Fantasy Review would long since have given up the struggle. Only the continued support of its advertisers-which made it possible in the flrst place-has enabled ii to survive and' encouraged by the tangible entirusiasm of its comparatively small number of subscribers, develop into somet'hing more substantial than it was in its first two years of life. The letters we have published since its enlargement give evidence of the desire of its readers for more frequent publication; and we wish we were in a position to respond to this demand. Instead of which, due to production difficulties which we are powerless to resolve at present. $e have to announce that it becomes necessary for us to issue Fa.ntasy Review a,t quarterly intervals, as a temporary measure. OnIy thus can we contrive to maintain both the standard of contents and regularlty of appearance which have made its reputation, and at the same time embark on the further development which is essential to its progress in other respects. At first sight, this might seem a retrogressive step. But although subscribers must now wait longer for each lssue' they wi]I soon be aware of the improvements which the less frequent publishing schedule will permit us to introduce as from the next (Autumn, '49) issue, which will see a modiflcation in the title of this journal the better to convey the greater seope of its a$icles and features.